The following was excerpted from a new title from Synergetic Press called “The Anthropocene: The Human Era & How It Shapes our Planet.” This book, a visionary yet pragmatic and comprehensive exploration of the biggest questions we face as a species, is the fruit of 7 years research by award winning science and environment writer Christian Schwägerl.

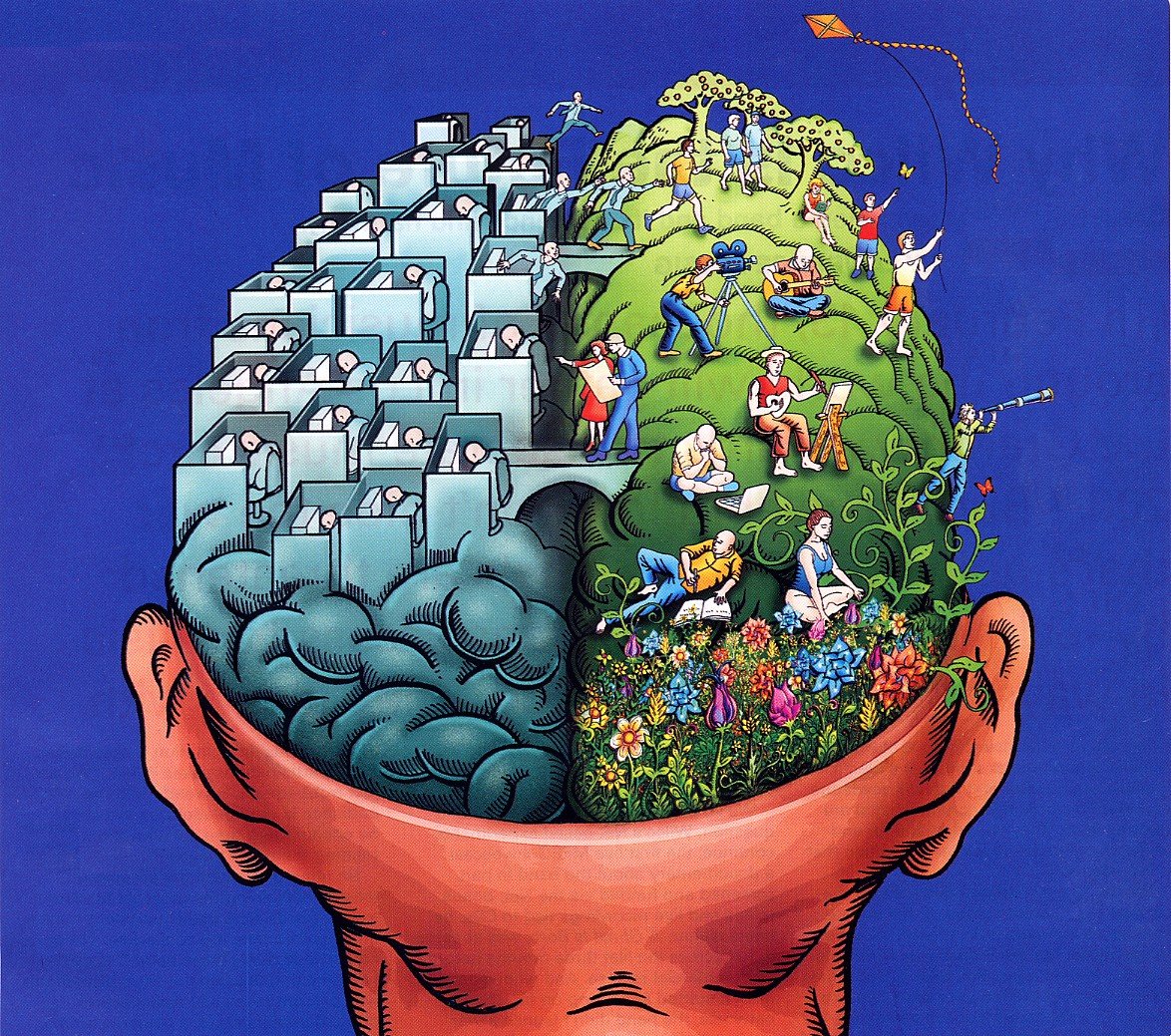

The best news for a good Anthropocene is that the human brain is a master at learning and relearning and that “rewiring” takes place all the time. Until old age, learning processes can cancel out old habits. Addictive and behavioral pitfalls can be replaced with new ways of living.

For decades, neuroscience told us that the brain was hard-wired and not really able to evolve after childhood. This view was based on a dogma held by the founder of modern neuroscience, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who stated in the early twentieth century that the brain matures at an early age and remains inflexible, limited and unchanged for the rest of our entire lives. But this dogma has proved to be completely untrue. With more precise analytical methods, researchers are now able to see that in fact, the human brain constantly forms new synapses and cells, even into old age, while continually changing its structure under the influence of new stimuli and experiences. Brain researchers’ new favorite term is therefore “plasticity,” that is changeability and dynamism. When people change their lives, their brains also change. A person who habitually hops into his car for any length of trip, but is so impressed by an article on climate change that he starts riding a bicycle and using public transport, is unintentionally changing the structure of his brain. The changes are small biochemical alterations but they can have far-reaching, tangible effects. Only a few weeks later, the rewards from cycling—better fitness, fresh air, more direct contact with other people—have become the new normal.

The plasticity of the brain puts each person in a very responsible position. Through your own actions, you can either strengthen old networks or you can stimulate the development of new nerve cells and connections. In this way, we can reinvent ourselves through our behavior and cultivate our needs and attitudes. We can either make the old paths deeper in the same way that a river carves out its bed; or by making an effort, create new paths that guide the water elsewhere. This ability to relearn, regenerate and to trust in the positive is now society’s most important resource—pervading all generations, from the elderly who grew up in the economic miracle of the 1950s and 60s, to the youngest, who are already learning about environmental problems in elementary school.

What it means to live in the Anthropocene is different for everyone depending on each person’s circumstances, priorities, environment and aims. But it can be said with a fair amount of certainty that our everyday lives will have to look different if the Anthropocene is to take a more positive course. Part of this is to see through the reward mechanisms that make consumerism addictive; to be prepared to pay a suitable price for products made with care; and to become involved as a citizen in local, regional or global issues.

What would happen if 7 billion people did what I do?

My lifestyle multiplied by 7 billion =?

This is the fundamental issue of life on a planet crowded with people. In the Anthropocene, individualism means to take responsibility for the whole, in the sense that d’Holbach described. There are many things in life that remain unaffected by this multiplication and many things to which it is not usefully applied. The idea is not, of course, that all people should live in a similar or even the same way. But this calculation can protect us from many wrong actions and instruct us to be more cautious. To take our own behavior as the norm gives us the right feeling for the scale of what is happening.

It can help us develop a new sensorium for what our own lives set in motion in the world. We can try to assess how much energy and material we consume—and redesign our behaviors. We can develop an aversion to products that are hard to repair or difficult to recycle. We can set upper limits to our consumption of fossil fuels. We can consider the global consequences of buying industrial food and stop throwing food away., We can eat meat once or twice a week instead of every day. We can become involved in the multitude of initiatives that nudge small, positive changes, like creating a local system of bicycle highways, looking after a nature reserve or sponsoring the education of children from poorer families. And we can be open to spending money on the living world instead of dead matter: the cell phone industry grew from nothing to an industry worth billions of dollars within twenty years. So why should it be unusual to pay for conserving living communication networks in forests, marshlands and savannahs, on whose functions nature’s services and our survival depend? The market for bottled water—a resource that is available in industrial countries from the faucet for a fraction of the price—adds up to 60 billion dollars. So why shouldn’t we pay for carbon dioxide mitigation so that glaciers remain in place as fresh water reservoirs? It has become the norm to pay three or four dollars for a coffee—so why shouldn’t it be normal to cover the costs of preserving the rainforest around coffee plantations, which, after all, increase their fertility?

The remarkable thing about consuming less and investing in good causes is that it often increases satisfaction. The idea behind gross domestic product (GDP) doctrine, that constant growth is necessary, is being questioned by many. Of course, our economies need to stay dynamic, innovative and competitive. A planned economy dictated by ecology in which everyone is allocated his or her portion of gasoline or bread, and which pays homage to Mother Earth in the fashion of North Korea, would be the least capable of guiding us positively through the Anthropocene. Rather, it is more about choosing the right way of life with our free will. From the individual to the state, from NGOs to multinationals, the Anthropocene is a collective learning exercise, an ongoing intelligence test for the human race.

There are already many encouraging projects, forward-thinking company managers, courageous activists, and other people who change their lifestyle in a consequential way. But for something truly new to be created, the forces of science and technology must be unleashed too. New technologies will not pave an easy path for us in the Anthropocene. We can’t count on technological silver bullets that make it unimportant whether climate conferences fail and which lifestyles we choose. The hope that there might soon be a magical cooling gas, which could help us stop global warming is just as unfounded as betting on progress in chemistry as a way of solving global malnutrition. Nevertheless, without a blossoming culture of science that is made up of millions of well-educated, creative and inquisitive minds, decisive changes will fail to materialize. If climate meetings continue to break down, the responsibility of scientists to analyze the state of earth and develop new, environmentally friendly technologies will be all the greater. And for this, sufficient numbers of qualified people and resources are required.