Last April, a Canadian ayahuasca tourist rode a motorbike into the Amazonian township of Victoria Gracia, sought out the venerated 81-year-old Shipibo healer Maestra Olivia Arévalo Lomas, pulled out a gun and shot her dead. Until that day, Victoria Gracia had been a calm if somewhat impoverished settlement a little distance outside of the city of Pucallpa. After that day, it became a traumatized and fearful corner of Peru, its Shipibo inhabitants suspicious of everyone and everything around them.

The motives and circumstances of that first murder are molded over with rumor, gossip and speculation. But the event became the subject of national and international news stories when Maestra Olivia’s murder was avenged locally and immediately, outside of the regular state-based channels which rarely move in to serve local justice. Police in uniform and in plain clothes descended on the community, seeking a few people allegedly identified in a smartphone video of the vengeance recorded and sold by a witness. The state became heavily invested in the outcome of the case as the Canadian government demanded some answers and a Congressman publicly called the Shipibo people ‘savages’. NGOs poured in feeling that they had to do something but with little idea of what they needed to do. And there was an outpouring of sympathy from the growing international ayahuasca community – with a few healing centers also issuing reassuring notes to their foreign clientele that they shouldn’t worry, they should keep coming as they were not in any danger. Outside Peru, the psychedelic renaissance movement honored Maestra Olivia in the comfort of their western homes. Many who didn’t even know her wanted to organize an event in her name, there, here, in Europe – efforts that for the most part were blatantly self-serving.

That initial moment has faded. NGOs have left, foreigners have forgotten, and ayahuasca tourism is doing what ayahuasca tourism does – come in, get the medicine, feel unified with the universe, go back. However, as the state prosecutors issued the first orders of preventive detention, whilst barring the settlement’s leaders to leave the area, the indigenous community is left with no choice. It cannot up and leave. It is there still, trapped, beleaguered, haunted and traumatized by the events, by the continuing policing of their community, fearful of any foreigner coming in, awaiting injunctions of the court without any resources to pay for legal fees, for schooling, for the care of children and families who have been affected.

The fallout from the murder of Maestra Arévalo Lomas is emblematic of a common problem, what we are framing as spiritual extractivism.

It was with this in mind and in the long shadow cast by these events that the Consejo Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo (Coshikox), the representative body of the 35,000 strong Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo people of the Peruvian Amazon, called the first ever convention of practitioners of ancestral medicine in the city of Yarinacocha at the end of August.

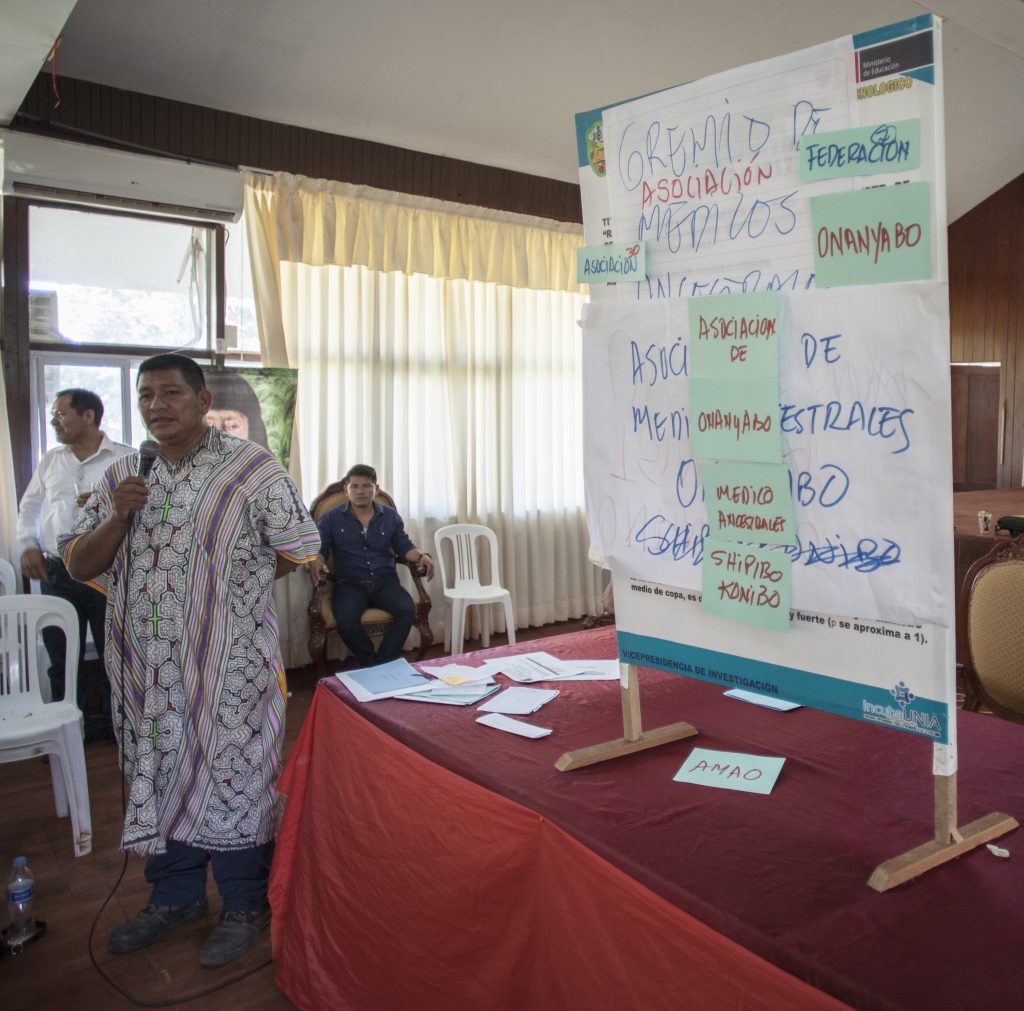

Almost one hundred people showed up. And in what felt like a historic event, they formed a union of healers. “The work of healing and the struggle for self-determination… must move forward on the same path,” the union stated in their final declaration, dubbed the Declaration of Yarinacocha.

More often than not, these two worlds – the political reality and the spiritual healing – are kept conveniently hidden from each other. As the declaration states, the opportunities opened up by the international interest in Shipibo medicine, ayahuasca in particular, has come with some dangers – and its popularity has done little so far to address other larger political and socio-economic concerns.

Hundreds of ayahuasca centers have cropped up around the Amazon. Having spoken to a wide range of healers and workers, we believe that the majority of centers, for the most foreign-owned, exploit their employees, do not pay them fair salaries and often neglect their health issues. Very few of them are concerned with the transmission of knowledge to the younger generations of Shipibo and the political struggle for territorial sovereignty. Thousands flock there from abroad for their ceremonies and speak of expanded consciousness whilst Shipibo communities diminish physically, as extractivism, contamination, territorial encroachment take their toll.

In the case of the settlement of Victoria Gracia, for example, it has fallen to Coshikox and its leader Ronald Suarez Maynas to step in with meager financial and legal help. Suarez Maynas himself was dogged for months after the events, as he made some very strong statements and organized a march against the racist Peruvian Congressman Carlos Tubino Arias-Schreiber who came out to call the Shipibo ‘savages’. The police knocked on Suarez’ door at night several times. He received multiple death threats, which like many other indigenous leaders and environmental organizers he has received in the past. Thanks to the way in which Coshikox organized politically against state aggression, those threats have receded. But every organizer and many communities live with that worry day and night. Several community leaders have been intimidated or even jailed for trying to stop deforestation, for fighting against oil and palm oil interests as these brutally encroach on the collective land of indigenous communities. Ayahuasca tourists don’t bother to look.

It’s rarely mentioned, but healers are migrating out from their villages to more urban locations accessible to tourists. Their communities are left with no health-care providers. Without a plant-remedy, the only option becomes a boat ride to an urban pharmacy. This is just part of the general out-migration that is making rainforests even more vulnerable, weakening the stewardship of the indigenous communities. Research demonstrates that indigenous lands have lower rates of deforestation than national parks, nature preserves, and private sanctuaries. Nevertheless, despite all of the proof, indigenous peoples as forest guardians are often left alone to face their struggles. As Shipibo activist, Robert Guimaraes Vasquez put it in a powerful intervention at the convention: “An indigenous community that has no healer is doomed to lose its territory as well.”

People come to the Amazon to heal themselves of the culturally specific ailments of industrialized, individualistic societies – from addiction to depression to sexual, military and other forms of trauma to eating disorders and diseases and illnesses that have found no real cure in the halls of Western medicine. Then they get to leave but they leave behind traces of their ailments, trails of inequality, frustration, violence, and sometimes legal cases. But their consciousness has expanded! They have experienced the way of light!

This is spiritual extractivism. We have to recognize that ayahuasca tourism is part of a much wider spiritual ecology and political economy, part of structures of global inequality, of predatory capitalism, of EuroAmerican lifestyles and thirst for growth, of the rampant militarism and corporatism of states that everyday affect the health of the Amazon and its peoples.

Will the enlightened and the healed help the overwhelming fight against big companies eating up the rainforest and destroying the territorial survival of the very Shipibo communities from whom they are receiving so much benefit? Will they put their bodies and resources on the line? Or will they be part of what Franz Fanon, referring to colonialism, called the greater organism of violence?

Whenever something happens to tourists, the news hits the press. There are legal and international inquiries. Westerners, often worried about their own well-being, and politicians, worried about the reputation of their country, call for regulations. But that is misguided. State-regulated matters have most frequently worked against indigenous groups. For example, the Ministry of Culture, which in some cases does officially endorse and recognize practitioners, and the Ministry of Intercultural Affairs, in charge of indigenous matters, have both fought cases against the hard-won law of ‘prior consultation’ – consulta previa – which demands that the state and private industry consult with and obtain the approval of affected communities and settlements for big projects that affect their lives and territories. Similarly, official conservation areas, in the name of protecting the environment, have frequently hampered the lifeways of their indigenous communities and led to displacement, whilst their so-called allies dream of eco-tourism ventures. Regulatory organs often benefit the predators.

The union of healers and the adopted Declaration of Yarinacocha interrupt the default call for state regulation and protection of foreigners. Taking a position against spiritual extractivism and towards Shipibo self-determination, they flip the coin: how are tourists and their economic, spiritual and cultural predation to be redirected?

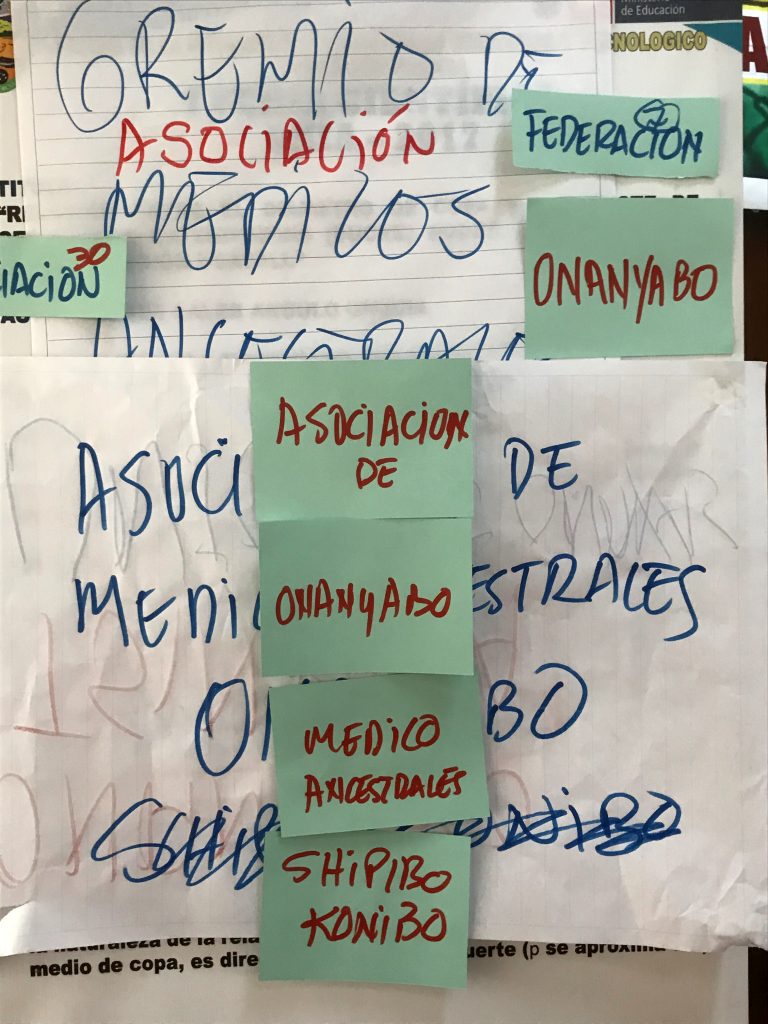

Following two days of complex, open discussion and rigorous deliberation in the Shipibo language – spanning topics from colonialism, tourism, science, religion, territorial integrity, fair salaries, exploitation and abuse, to intergenerational knowledge transmission, state policies, the political and economic condition of Shipibo communities, and collective and individual rights – the convention rejected the terms “shaman” and “shamanism” as imports that did not capture the historical specificity of their work; the Shipibo term Onanya was adopted, with the qualifier Ancestral Healers (Maestros de Medicina Ancestral). Accordingly, the union was named The Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo Association of Onanyabo/Ancestral Healers.

The union makes a powerful claim when it states that in terms of its history, practice and methodology, traditional healing and expertise in medicinal plants has been part of anti-colonial resistance and must remain so. In full solidarity with the Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo struggle for sovereignty and the understanding that traditional healing is a political practice, we stress our full support for the declaration and its principles and urge all foreign organizations, visitors and users of Amazonian medicine to heed its principles, and ask themselves what they are contributing to that struggle.

Yarinacocha Declaration

Issued on August 19th 2018 at The First Convention of Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo Traditional Medical Practitioners

Pre-occupied that the knowledge of plants and practices of the Onanyas – Ancestral Healers are being lost and not being transmitted to future generations;

Recognizing the repercussions of colonialism, state-based and Western education, and the invasion of industrialization, which has threatened the ancestral practices and knowledge of Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo Peoples;

Recognizing the great expansion of spiritual tourism in Amazonian territories, and that the international interest comes with opportunities as much as dangers for the on-going development of ancestral knowledge;

Recognizing the importance of coordination and agreements between Onanyas for confronting the opportunities and for discussing strategies to address the problems of our communities, which have been dramatically highlighted by the assassination of Maestra Olivia Arévalo Lomas;

We declare that:

- Given their history, practice, and methodology, Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo healing and expertise in medicinal plants are anti-colonialist forms of practice and knowledge, able to resist, transform and reconfigure with every difficulty and threat. Thus healers, teachers, practitioners must remain aware and proud to cultivate the anti-colonialist nature of their practices.

- The work of healing and the struggle towards self-determination are not separable. They must move forward on the same path.

Consequently, we

- Adopt the term Onanya – Ancestral Healer to replace the common ‘shaman’ and ‘shamanism’, imported terminologies that do not apply historically to the particularities of our culture.

- Suggest that Onanyas can focus on the training and education of Shipibos youth, especially in the communities, so as to counteract cultural appropriation by foreign apprentices who numerically overshadow local ones since our young populations do not have comparable economic resources to engage in long periods of training.

- Invite Onanyas, practioners, workers and students (indigenous as well as foreign) to be conscious of the politics of Shipibo sovereignty, and to contribute to the struggle for cultural, economic and social self-determination.

- Propose the establishment of a school, ‘Escuela Meraya’ (in accordance with values of this declaration) that would include education in plant medicine, politics, and art as well as in digital, vegetal and spiritual technologies.

- Will investigate the development of a mechanism by which foreigners taking advantage of indigenous medicine, healing and spiritual labour might be able to contribute to the cultural and political empowerment of Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo Peoples and their path towards self-determination; such a mechanism could include, for example, a tax or contribution for each ‘pasajero’ (foreign patient) to be donated to an organization such as the ‘Escuela Meraya’.

- Invite Onanyas, to join the Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo Association of Onanyas/ Ancestral Healers so that they might coordinate in unity and demand their rights and fair and just remuneration.

***

The Shipibo Conibo Center is an art project in the form of a nonprofit cultural organization set up to promote and perpetuate the creative life-ways, knowledge and sovereignty of the Shipibo Konibo people of the Peruvian Amazon.

Consejo Shipibo-Konibo-Xetebo (Coshikox)

http://www.coshikoxperu.org/