Everyone is born with a body. A body that will—to the best of its abilities—help manifest the conscious human experience. Throughout time and history, human civilizations engaged in body modification practices as a vehicle for cultural, ceremonial and individual expression. Whether through fashion, makeup or personal aesthetic, people’s ability to control their outward presentation not only affects their peers’ perceptions of them but can also influence their personal identity. The Amazonian frog medicine practice leaves participants with kambo scars they sometimes carry with them for their lifetimes. How does a visual reminder of the human body affect personal and social identities? Let’s explore kambo scarring, body modification and the implications and inspirations of choosing to alter the human form.

Kambo Scarring

Kambo medicine relies on the defensive secretions of the Phyllomedusa bicolor, commonly referred to as the giant leaf frog. Indigenous peoples of the Amazonian basin applied these secretions to methodically burned points along the human body, allowing the frog’s venom to quickly enter the blood and lymphatic system beginning the ceremonial purging process.

Depending on the participants’ desired goals and demographics, shamans place the small round burns—achieved by pressing the coaled end of the wooden stick into the skin—on different parts of the body. The ceremony often takes place over two sessions, sometimes leaving two neat rows of scars or completing a circle of burn points on the participant’s skin.

In traditional rituals, the ceremony was a precursor to hunting exhibitions and the medicine served to strengthen the hunter’s mental and physical fortitude. More extensive kambo scarring signified a hunter’s connection to the ancestral wisdom and physical and psychological strength.

Usually, shamans placed these scars on a hunter’s shoulders, chest or arms: all areas associated with strength and virility. In order to promote fertility in women, shamans applied the frog secretions to burns on the legs and stomach.

These markings can fade over time, as the burn wounds heal and scar tissue ages, but the general consensus between indigenous understanding and the western application of kambo is that these scars are badges of honor meant to be worn with pride.

Let’s take a look at some other forms of body modification to better understand how altering one’s body influences personal and cultural understandings.

Body Modification History

The physical vessel is the primary canvas for people to present to the world: who they are and how they fit into the society around them. Though race and gender affect people’s ability to move through society, these characteristics are unchangeable, making body modification an available vehicle for distinguishing individuals within their own communities or signaling ingroup affiliation to the outside world.

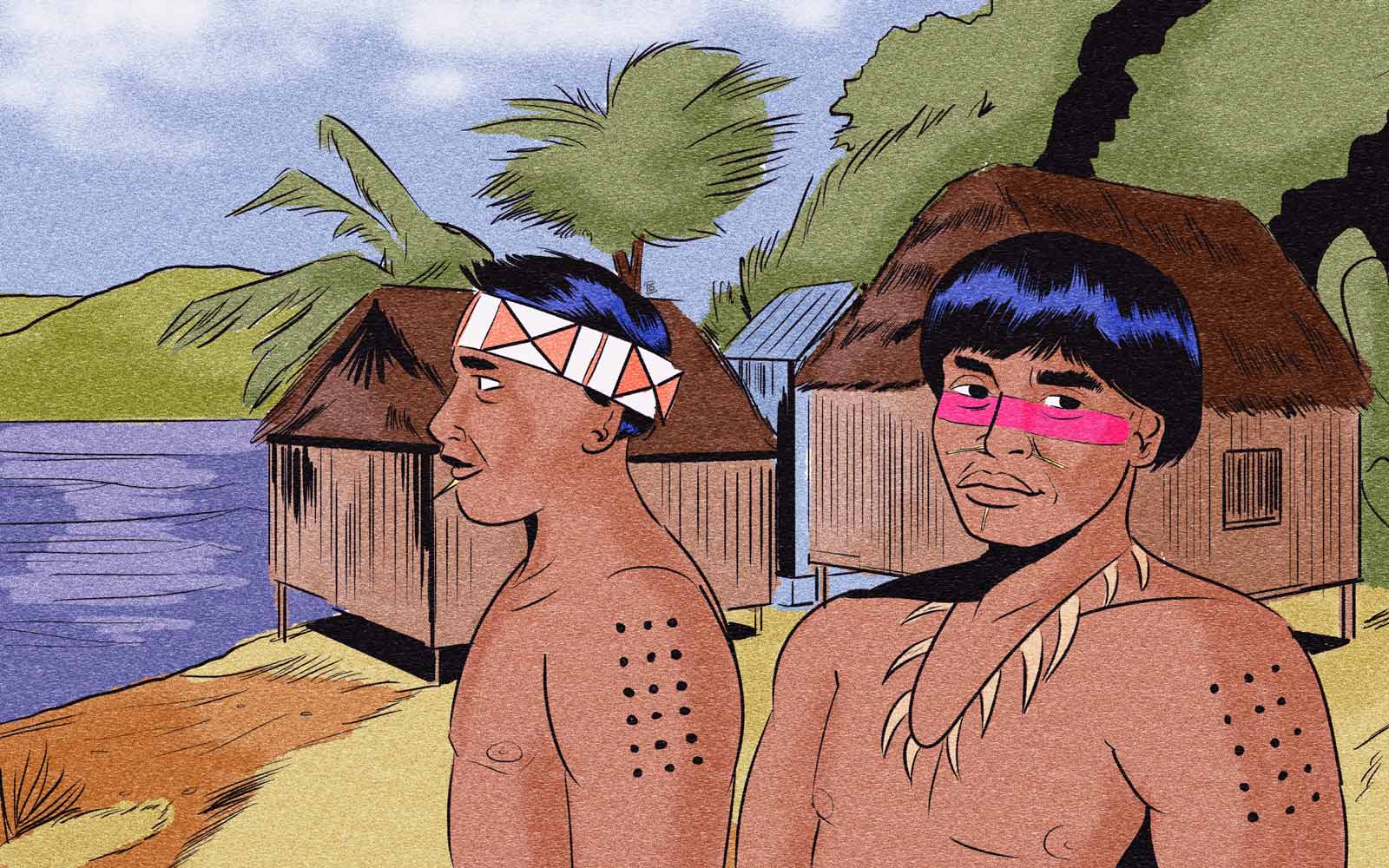

In the hot Brazilian Amazon, indigenous communities usually wore minimal clothing, making piercings, hair, scarring and body art a visual representation for different tribes to distinguish each other—and later for colonists and researchers to establish pejorative otherness.

Tribesmen and women had different roles in traditional Amazonian societies, reflected in the gendered body modification traditions. Male’s scars or piercings often signified their leadership, strength or physical abilities. For females, body modification often showed marital status, signified fertility or past childbirth.

Aside from kambo scarring, some indigenous Amazonian men engage in traditional lip piercing practices using labrets. Labrets are plugs or plates that signify a boy’s transition to manhood, starting as small plugs and progressing to larger plates as they age into men.

Body modification as a representation of the progression into adulthood is present outside of indigenous contexts. Ear piercings are often one of the first forms of body modification available to young people and can also serve the purpose of providing an outlet for rebellious bodily autonomy. States in the US have laws prohibiting body modification—like tattoos or piercings— until a certain societally agreed-upon age of adulthood. Parental consent forms can get around this stipulation but still perpetuate the notion of body modification as a vehicle for expressing adult physical autonomy.

Let’s take a look at the global implications of body modification and how altering the physical form impacts people’s psychological self-concepts.

Implications of Body Modification

Body modifications affect the internal wearer as much as they influence the perceptions of the outside observer. The symbolic meaning of body modification depends on the cultural contexts and desires of the individual. Throughout history and in both indigenous and westernized settings, body alterations help people understand their own identities and share their internal selves with others.

Research looking into how clinical therapy can better serve clients found that by instigating conversations about tattoos or other physical alterations therapists gained a valuable window into their patient’s psyche. Making a decision to permanently change the physical form can be an authentic expression of self-actualization. This self-actualization can also influence social relationships.

Tattoos and piercings have often been associated with counterculture and rebellion against societal norms. As trends fluctuate and body modifications—like plastic surgery, tattoos and piercings—become accepted in mainstream culture, the underlying self-actualizing motivation remains.

Body alterations can allow people to conform to societal standards and traditions. The rising popularity of plastic surgery is questioned by some as the proliferation of an idealized concept of beauty. To others it is but another form of self-expression and actualization: an intrinsically owed choice to practice autonomy over the physical self.

Conforming to societal body modification traditions also allows people to connect with their own cultural backgrounds.

Many traditional indigenous body-altering practices—like the Maori facial tattooing practice or the crocodile scarring of tribes in Papua New Guinea—allow community members to participate in traditions that connect them to the rich history of their ancestors. In some ways this is a confirmation to societal standards, but an important and valid form of cultural expression.

Body modification can help connect people with shared interests or backgrounds outside of cultural heritage. For example: Military related tattoos are incredibly popular amongst service people, signifying their time in the service as an important component of their identity. It feels good to be part of a group and visual demarcations can foster community.

Ingroup association occurs even when people use body modification as a way to distinguish themselves from a perceived unsatisfactory ingroup of origin. Tattoos—a form of body modification once viewed as shocking enough to land people in a hall of carnival freaks—now has many various styles, cultures and groups with fervent beliefs about best practices and even a hierarchy of tattooing.

There is also valid criticism of the appropriation of traditional cultural tattoo styles by outsiders, though the discretion and intention of all participants is the ultimate judge and jury.

The connection between body modification and identity can also be co-opted by groups seeking to generate a toxic ingroup affiliation. Cults, gangs and terrorist groups often use tattoos or scarring as a way to instill a permanent reminder of obligation and curtail members from leaving the group.

Everyone has different motivations behind their decision to alter or preserve their physical body. In the case of kambo medicine, physical alteration is accompanied by an intense psychological transformation. Not only are the scars a badge of honor to the outside world but a symbol of the entire ceremonial process and any insights gained from engaging with kambo medicine.

More research is needed to understand how kambo scarring—opposed to other medicines like ayahuasca—affects the long-term wellbeing of ceremony participants. Though the wounds will lighten from scarlet scabs and fade into scars, the impact of the kambo experience—one known to connect people to divinity, ancestral wisdom and heal deep-rooted trauma—has the potential to change ceremony participants for a lifetime.

What do you think about the implications of body modification and self-actualization? Do you think the scarring process involved in kambo medicine changes what ceremony participants get out of their experience? We would love for you to engage in the comments below. If you are interested in learning more about endogenous medicines make sure to subscribe to our newsletter for updates on the latest content.