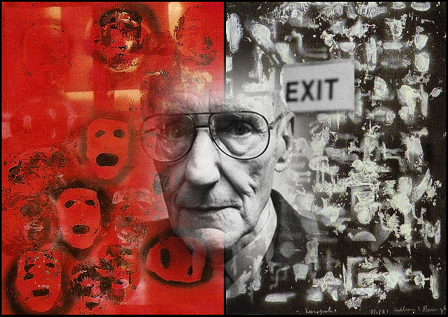

2012 was definitely a year of All-things-Burroughs. As well as Viggo Mortensen's acclaimed cameo as ‘Old Bull Lee' in the long-awaited film version of On The Road and the 30th anniversary of The Final Academy (with its attendant publication, Academy 23, and celebration @ The Horse Hospital) — we also had two substantial additions to our appreciation and evaluation of William S. Burroughs, this time in connection with the visual arts: firstly, LA-based British artist/designer Malcolm Mc Neill delivered (with the help of Fantagraphics) a beautiful two-volume set showcasing The Lost Art of Ah Pook — accompanied by Observed While Falling, a fascinating memoir of the meeting between the young McNeill and Burroughs in 1970, and the ensuing friendship and collaboration; and currently The October Gallery in London, which has a longstanding relationship with the work of William S. Burroughs — also his friend and erstwhile collaborator, Brion Gysin — is showing "All out of time and into space" a new exhibition featuring his paintings, drawings, and "talismanic objects" which seeks to emphasise the visionary aspect of his work. According to the press-release, the show's title "references Burroughs' concern with ecological crisis in the age of space exploration" — and in an essay in the accompanying catalogue, his long-time associate, editor and collaborator James Grauerholz explains "William was a Foreseer" who "foresaw our new century" and "into the shadows of his times."

It seems timely to revisit William's beginnings as a visual artist, now that such reassessments and re-evaluations are being made, and consider what his concerns and motives may have been at the beginning.

1988: William S. Burroughs was in town for the Launch of his paintings at The October Gallery, and I was there to meet him. I got to generally ‘hang out' during all the press hoopla, and was treated to a guided tour of the paintings by the man himself, during which time I conducted an informal interview which was meant to be the basis for an article in Square Peg (a glossy, coffee-table ‘Gay Arts' review of the late 80s, in which Derek Jarman's boyfriend Keith Collins had editorial input: he had suggested that if I wrote a piece, or could get an interview, he would see that it was placed… but for reasons that were never clear to me they passed, and a rather badly cut version of it appeared instead in Wild Fruits, a Burroughs-inspired fanzine put together by various ‘Chaos Magician' & ‘Psychick Youth' friends of mine.)

I was then invited to come back for the Launch Party that same evening, where I will never forget being greeted by an obviously-already socially-lubricated William Burroughs coming over to me and my companion and exclaiming in his unmistakable, drawn out, almost snarling, drawl: "Hey, kemosabeeee… That's what we need in here, some young boyyzzz!!!" – After sprawling bear-hugs, he quickly regained his composure & hostly demeanour and waved airily to an attendant, "Oh I say, see that these young gentlemen get some drinks, will you?"

It was a wild evening, it was a wonderful evening. Faces, handshakes & hugs that passed in the drunken haze included: Kathy Acker, J. G. Ballard, Felicity Mason (Brion Gysin's ‘pseudo-sister'), David Medalla — and at one point a brief appearance from Francis Bacon, just long enough to be caught on camera with Burroughs & Medalla — Genesis P-Orridge, Sandy Robertson, and Terry Wilson and his ‘Third Mind' collaborator, Philippe Baumont, and so many others that I did not know then or cannot remember now…

I offer the following article-cum-interview from 1988 as a snapshot of a moment in time.

The Paintings of William S. Burroughs @ The October Gallery, 1988

William S. Burroughs has always been intensely interested in visual imagery: one of the longest-running collaborations & friendships of his life has been with the artist Brion Gysin; his articles, essays & novels demonstrate a fascination with the hieroglyphic languages of the Ancient Egyptians and the Maya; and his fascination with the Mayan glyphs, calendar, and lost books inspired the genre-defying, proto-Graphic Novel project Ah Pook Is Here which he worked at with English artist Malcolm McNeill on-and-off for over seven years (although in the end only the text was published, and sadly the "more than a hundred pages of artwork" by McNeill has yet to see the light of day.) In addition to his earlier scrapbook experiments, and collaborations with Gysin for The Third Mind, over the last few years Burroughs has collaborated on drawings and prints with artists Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Michel Basquiat, and Philip Taaffe. Following these collaborations he has developed a love of painting to such an extent that he now considers it his second career.

The Day of the Private View

On the morning in question I was running a little late and so arrived feeling a bit hot and frantic, but after a sit down and a cup of tea I managed to calm down and then had a good look at the pictures before the Old Man Himself arrived…

There were 26 pictures in all: paint and ink sprayed, stencilled, flicked, dripped and painted onto paper, board, plywood and tin, interwoven with collaged photos and shot through with bullet holes. The infamous shotgun paintings! I had first heard of these about a year ago from the writer Terry Wilson, but I had to admit that I found them considerably more impressive to look at than imagined.

After some time Burroughs arrived with his personal assistant, James Grauerholz — I was reminded of the description in Terry's novel, ‘D' Train:

"…the Old Man, long, thin, bent, like an ancient cantankerous, infinitely ominous arrival from another galaxy… his formidable gaze flickers over everyone present in a strange combination of total attention and complete indifference."

He was soon whisked off upstairs for a private meeting, and I had already been advised that there was no point trying to get to talk to Mr Burroughs as his interviews had all been booked in advance. I was hoping that, given the chance — and perhaps a little prompting — he might actually recognise me, or that mention of our occasional correspondence and some mutual acquaintances would jog the memory.

As it was, fate intervened: Terry Wilson arrived, even later than I had been, and we were just saying ‘hello' as Burroughs & Grauerholz came back down into the Gallery. He was of course an old friend, having met William & Brion back in about 1971, and been with Brion at the end (after they had completed the definitive Gysin statement, Here To Go: Planet R101 together) — so I found myself in easy, familiar company, and before too long it was "Oh William, you remember Matthew, don't you?" — for an instant I was subjected to the piercing gaze, but then I must have come into focus and the look softened, with the distinctive twitching of the corners of the mouth that passes for a smile with Burroughs — sorry, "William" (it's all first name terms here: William, James, Terry and Matthew, like we're all — well, if not ‘old pals', at least familiar colleagues) The ‘Old Man' is called away for a moment, Terry helpfully suggests I have a word with James, who "arranges everything for Bill."

James Grauerholz was polite and friendly, so big and American and clean-cut looking that I couldn't help but think of him as the captain of a High School football team. He shakes hands manfully, like he really means it, and we talk a little about some mutual acquaintances (well, I name-drop to jog his memory…) He advises me that William's schedule is pretty tight, and all the interviews were booked up well in advance, but "as you're an old friend" (we both smile at this, but warmly enough) I could talk to him for a while after his photo-session, while the TV crew are setting up for Richard Jobson (!) to interview him.

What follows is a composite from my Notebook, both about the paintings and our conversation as we walked around the Gallery, William giving me the guided tour:

Necropolis (1987, paint on black mat board, 20" x 16"), white paint fading into grey, hanging in luminescence against the black background. Decalcomanic splodges of white float in and out of different depths of ghost images, which on closer examination reveal themselves to be a grid of stencilled Egyptian hieroglyphs: an arm, a bird, a serpent across a broken square. City of the Dead. Hanging next to it, the companion picture, Cosmic Hock Shop, the same stencilled figures on black, except this time in gold, overlaid with wisps of gold and smeared silver, like blobs of molten metal, dripped…

Meeting William Burroughs as he comes in — a frail, slender figure, somewhat hunched — but there is strength in the handshake and in the piercing gaze, and in the voice when he tells a rather over-zealous Press-photographer "I think that's enough, don't you?"

How many photos have you had taken today?

"Hundreds…"

What do you think about when you're having your picture taken?

"Oh, nothing… absolutely nothing."

I ask William about his apparently late start in drawing and painting:

"Well actually I began about 25 years ago, doing collages and scrapbooks… that was when Brion said to me that writing was 50 years behind painting… but it's only since I moved to Lawrence it's become my second career."

Do you still keep scrapbooks?

"Nooo… I'm not really interested in that anymore, not as a form — but some of it has gone into these" — gestures around the Gallery with his cane — "the more collaged elements. For instance, I've gotten some very good effects by photographing a smaller section of one picture, then putting it in another one — painting around it. And then something like Space Door…" — already sold to Tim Leary, he chuckles — "…that has pictures from the National Geographic — pictures of the Earth from Space, and I thought My God – you could see how it was similar to what I was already painting, and of course what Brion had painted…"

Not surprisingly, several pictures (particularly Inspiration From Brion Gysin, Raining Red Frogs and Untitled: Black, White) show the influence of the calligraphic style of Brion Gysin, who studied and worked with Japanese and Arabic scripts in much the same way as Burroughs himself was drawn to Egyptian and Mayan glyphs.

Would you say that Brion was your main influence as a painter?

"Oh definitely… It was Brion who first taught me how to really see painting — and there were various things with him… drawings… collages, calligraphy — and all the material that went into the scrapbooks, but also The Third Mind."

And anybody else? Other inspirations?

"We-e-elll… I very much like the Old Dutch Masters, Van Gogh, but they don't have much to do with all this… Inspiration? Hmm… There's Klein of course, Yves Klein. Hieronymous Bosch. And I like Klee very much — ‘The Artist renders visible', he said — also Jasper Johns. And Pollock, who was a more careful artist than people realise — but he allowed things to happen — and you know yourself how important it is to be ‘open', to be prepared… What is that saying, about so-called ‘chance'?"

‘Chance favours the prepared observer?' (Pasteur)

"That's it! Yes! Precisely… it's all about… being prepared. These techniques — dripping, spraying, what you get with the shotgun blasts — they're all about introducing a random factor, the nagual, right? You know about the nagual, yes? Castaneda… But at the same time you don't just leave it there — I work on a picture with brushes, stencils. You don't just leave it to chance…"

And ‘how random is random' anyway?

"Sure, sure… To me, inspiration — or what some people might call ‘genius' — is the nagual: the uncontrollable — unknown and so unpredictable — spontaneous and alive. You could say the magical."

I've always thought that Brion's painting was essentially ‘magical' — the calligraphic works with their inspiration from cabalistic grids, the magic spells in Morocco…

"Oh absolutely! Brion was a magical artist, no question. And here" (he gestures at some of the more calligraphic works) "the pictures are painted up, down, crossways — like Brion's. So there is no ‘right' way up or down or… like if you were in Space. So they really are Space-Art!"

I ask James if there are any plans to put out The Cat Inside — text by Burroughs, with drawings of cats by Brion Gysin (currently only available in an expensive collector's volume from Grenfell Press of New York) in a more affordable, ‘popular' edition: apparently William certainly wants it to be but there are no plans to do so just yet. Also, fishing around on the subject of a Brion Gysin exhibition coming to London I was told that it is still at the "fingers crossed" stage, but that "it's looking good" (watch this space!).

He gestures around the Gallery, telling me the dates when various pieces were done. Standing in front of one of the ‘shot' pieces, I ask him about these.

"I started doing shot and painted works in 1982… I did about 30 in all and The Golden Boat dates from then" (plywood blasted with a shotgun, a photo collaged on of the porch at an old river-front house by the railroad tracks in Lawrence, where Burroughs stayed during 1980.) "It was just a way to introduce a random factor… but usually I combine that with silhouette and brush work, to introduce some sort of order."

The Curse Of Bast — one of a series of ‘Curse' pictures from 1987 — features collaged elements of a leaflet protesting cruelty against cats, a picture of a cat from ‘page 23' of a book in its upper half, and a ragged bullet-hole surrounded by an explosion of yellow paint. Lower right is an upside down press cutting with the headline ‘4 Injured in Arkansas Tornadoes' shot through with bullet-holes, from which jet out spurts of deep sea green.

(Terry Wilson points out to me that if you look through the holes in the middle of the picture you can make out either the word ‘Fire' or ‘Exit' on the door in the next room — the space beyond adding an extra dimension: looking at and through the picture. "Space-Art", like the man said…) On the reverse of the picture, almost ‘hidden', is a photo of a statue of the Egyptian cat-goddess Bast, under which is written the title.

The Egyptian references give witness to William's longstanding fascination with hieroglyphs, and his more recent study of Egyptian soul-craft (in part inspired by his reading of Norman Mailer's epic Ancient Evenings), which he has used to great effect in his recent writings — especially his most recent full-length novel, The Western Lands (1987), with which he closes the trilogy begun with Cities of the Red Night (1981), and followed by The Place of Dead Roads (1983). The title itself derives from the Ancient Egyptian name for the Afterlife: the place where the soul of the departed went, following the setting sun…

An almost calligraphic grid of vibrant red hanging against a softer reddish wash, given some kind of solidity and reflection by the sheet tin underneath — a photo of a cave painting showing two rather spindly figures of hunters with bows and spears — given a rather camp overtone by the appropriate title The Delicate Hunters.

Some of these look fetish-like, in the shamanic sense — they almost resemble cave-paintings?

"They're meant to! A number of them are meant to be spells… invocations. There are these ‘Curse' paintings…" (e.g.: Curse of the Red Seal, Curse Against Mohathir Mohamed) "…and there's a whole series of ‘Land of the Dead' paintings, illustrating The Place of Dead Roads and The Western Lands…"

"It is to be remembered that all art is magical in origin — music sculpture writing painting — and by magical I mean intended to produce very definite results." (WSB, from an essay on Brion Gysin quoted in Here To Go: Planet R101, by Terry Wilson)

Looking at a large paper covered in black edged green and yellow phosphorescent mists that suggest burning or radioactive vegetation, with a central picture of a man on horseback being frightened by a ghost, and in the lower right corner a photo that is hard to make out:

"The Devil Of Hyalta Stad, Sweden, 1750 was inspired by a passage in a book about apparitions and hauntings that somebody gave me, which is where the central picture came from."

And the other picture? A ghost photo?

"Oh, that was taken at an initiation rite in the Australian Outback."

There is an extensive use of stencilled and silhouette forms in the pictures such as the hands in The Milky Way, and the layered paper shapes and hot incandescence of Through A Fish Eye — changing levels, shifting, moving, collaged images swim in and out of hazes of colour and calligraphic grids… and the wide-mouthed, mask-like faces in Burn Unit:

"Now Burn Unit is definitely an illustration: you know ‘The Medical Riots of 1999' section in The Western Lands — when morphine is denied to a group of burn patients? "Morphine or Walk, MOW! MOW! MOW!" That was one where I was working with cut-outs, the mask silhouettes — and suddenly it was right there: a scene from the book."

There's a sense of finality about The Western Lands and I felt that many themes from your earlier work were in some way resolved. I'd heard rumours that this was to be your last book — was it in fact a conscious effort to bring to a close your career as a writer and tie up any loose ends?

"Oh no… Western Lands is just the end of a cycle. But I'm already writing another, a short novel – Ghost of Chance…"

About?

"Jesus Christ!" A nod and an almost imperceptible twitch of the mouth that could be a grin. "And lemurs, and Captain Mission and the pirates – set in Madagascar. And then there's the Museum of Lost Species – or Extinct Species, rather. There's a lot in there to do with magic, and miracles. I think that Christ probably did exist, and that he performed at least some of the ‘miracles' that he is credited for… But that's not such a big deal, I mean… healing the sick, weather magic – any competent medicine man can do weather magic – I've seen it done myself. And as for casting out devils, he can cast out devils. Particularly if he put the devils in there in the first place! ?The Buddhists of course take a pretty dim view of all of this – healing, miracles, weather-magic – the lot…"

And do you intend to carry on painting?

"Oh, most definitely, yes! There will be about ten or twelve new paintings in Ghost when it's finished."

Our informal chat draws to a close as a girl with a clipboard indicates that it is time for the TV interview. William rolls his eyes. James brings him a cup of tea, gives me the address of ‘William Burroughs Communications' and asks that I send a copy of my article ("for the files") – also a copy of my own ‘Third Mind' collaborative writings that William has been generous enough to say he finds "Accurate and honest" and deadpans "Young boys need it special!" Words that we have all heard before, but for now I am flattered enough that he would bother to say anything at all… They will look forward to receiving it. Later that week, they have a dinner-date with my friends Geff & Peter of Coil, so we will see each other again. And will I not be coming to the Opening that night? Well, if I'm invited — of course, how could I not?

I get William to sign the copy of the Catalogue I've been given, then we all shake hands again and say we will see each other later that evening.

Thank You, William

"My pleasure, Matthew. My pleasure."

–Matthew Levi Stevens, 1988

The Lost Art of Ah Pook & Observed While Falling by Malcolm McNeill are both available from Fantagraphics. "All out of time and into space" is at The October Gallery, London until 16th February 2013. A catalogue is also available. A Moving Target: Encounters with William Burroughs by Matthew Levi Stevens is available from Beat Scene Press, or direct from the author via www.whollybooks.wordpress.com