The following is Wade Davis’s foreword to Rainforest Hero: The Life and Death of Bruno Manser by Ruedi Suter, published by Bergli Books.

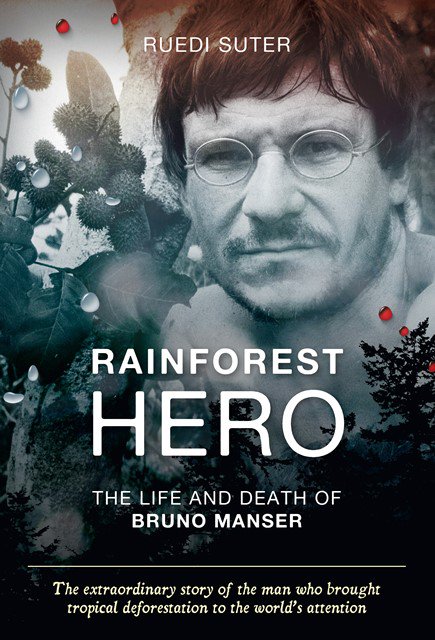

My plane to New York had been delayed four hours and that’s how long Bruno Manser had been waiting in the lobby of the Regency Hotel. He was dressed in a sleeveless wool vest, faded trousers and sandals. His arms were bare, save for dozens of blackened Penan dream bracelets that hung on his wrists. Short and sinewy, with dark hair shaved by his own hand and rimless spectacles hugging the bridge of his nose, he really did look like Gandhi, just as the Malaysian press had reported.

He was hungry, but without a dinner jacket he had been barred from the hotel restaurant. Here was a man who had disappeared into the rainforest of Borneo and remained there for six years, relinquishing all contact with the modern world to live as a hunter and gatherer with the nomadic Penan. Here was the Swiss shepherd whose vision of a world without greed collapsed in the face of the most rapine deforestation known on the earth. Here was the reluctant warrior who brought the Penan to barricade the logging roads, electrifying the international environmental movement and stunning the Malaysian government, which placed a reward on his head and hunted him down with police and military commandos. Apprehended twice, he escaped and, protected by the Penan, eluded capture for three years. Dismissed in Malaysia as a latter-day Tarzan, the man became a lightning rod for all the forces gathered in the struggle for the world’s most endangered rainforest. But in New York, without a jacket, he couldn’t enter a restaurant.

Anticipating the problem, a friend arrived for dinner with an extra coat, which made Bruno appear absurd enough to satisfy the maitre d’. It was Sunday night and the restaurant was empty. The meal passed calmly until, just as it was time to pay the bill, a rat appeared and scampered the full length of the restaurant. Within moments three waiters and the maitre d’ were hovering at our table, spewing apologies. Bruno raised his glass. ‘It was a Norway rat,’ he said to them, ‘and it wasn’t wearing a jacket.’

Such wit was typical of Bruno Manser. Even as he campaigned throughout the world on behalf of the rights of the Penan, meeting with heads of state, religious leaders, ambassadors and celebrities, he maintained a certain lightness of being, a sense of whimsy that endeared him to many and no doubt frustrated a few. He was certain of the righteousness of his cause and he would do whatever it took to bring it to the attention of the world. He chained himself to the top of a lamppost in London, parachuted into the Earth Summit in Rio, climbed a 300-foot tower in Brussels to hang a protest sign. He attempted to make peace with Sarawak’s notoriously corrupt Chief Minister, Taib Mahmud, by trying to bring him a lamb. He undertook a hunger strike that lasted for sixty days. When I introduced him to a literary agent at William Morris in New York, Bruno stunned the agency team by driving a knife into the wooden wall of their posh boardroom and announcing that it was made from tropical timber. At a meeting at Warner Brothers in Los Angeles, he left the head of production and her team slack-jawed as he recalled the time he was struck in the leg by a deadly pit viper. In a relaxed tone that left no doubt as to the veracity of the tale, he recalled cutting away the flesh, reaching into the wound with a fish hook to try and retrieve the muscle, and then binding his leg with a length of rattan fiber. As he pulled up his trouser to reveal the hideous scar I was certain that several in the room were about to faint.

Bruno once told me that the Penan do not separate dreams from reality. ‘Every morning at dawn,’ he said, ‘gibbons howl and their voices carry for great distances, riding the thermal boundary created by the cool of the forest and the warm air above as the sun strikes the canopy. Penan never eat the eyes of gibbons. They are afraid of losing themselves in the horizon. They lack an inner horizon. If someone dreams that a tree limb falls on the camp, they will move with the dawn.’

Tragically, by the time Bruno disappeared in 2000, his fate uncertain, the sounds of the forest had become the sounds of machinery. Throughout the 1980s, as the plight of the Amazon rainforest captured the attention of the world, Brazil produced less than three percent of tropical timber exports. Malaysia accounted for nearly 60 percent of production, much of it from Sarawak and the homeland of the Penan.

The commercial harvesting of timber along the northern coast of Borneo only began, and on a small scale, after the Second World War. By 1971 Sarawak was exporting 4.2 million cubic meters of wood annually, much of it from the upland forests of the hinterland. In 1990 the annual cut had escalated to 18.8 million cubic meters.

By 1993 there were thirty logging companies operating in the Baram River drainage alone, some equipped with as many as 1,200 bulldozers, working on over a million acres of forested land traditionally belonging to the Penan and their immediate neighbours. Fully 70 percent of Penan lands were formally designated by the government to be logged. Illegal operations threatened much of the rest.

Within a single generation the Penan world was turned upside down. Women raised in the forest found themselves working as servants or prostitutes in logging camps that muddied the rivers with debris and silt, making fishing impossible. Children in government settlement camps who had never suffered the diseases of civilization succumbed to measles and influenza. The Penan, inspired by Bruno, elected to resist, blockading the logging roads with rattan barricades. It was a brave yet quixotic gesture, blowpipes against bulldozers, and ultimately no match for the power of the Malaysian state.

As recently as 1960, the vast majority of the Penan lived as nomads. By 1998 perhaps a hundred families still lived exclusively in the forest. Today there are none. Throughout their traditional homeland, the sago and rattan, the palms, lianas, and fruit trees lie crushed on the forest floor. The hornbill has fled with the pheasants, and as the trees continue to fall, a unique way of life, morally inspired, inherently right, and effortlessly pursued for centuries, has collapsed in a single generation.

Bruno Manser bore witness as the basis of the existence of one of the most extraordinary nomadic cultures in the world was destroyed. The nomads were his friends. He returned to Borneo in 2000 to make a film. When the project ended, and the film crew departed, Bruno walked alone into the forest, much as he had done so many years before when he first went to live with the Penan. He was last seen alive on 25 May. A subsequent search led by the Penan turned up not a trace, nor any evidence of what became of him. He may have died of natural causes, or perhaps by accident, drowning in a river, or falling out of a tree, or dropping off a cliff face. Bruno loved to climb. His fate remains unknown, though many believe that he was murdered.

Bruno’s story deserves to be told because in a world tainted with greed, in which the violation of nature is the foundation of the global economy, his life and message stand apart as symbols of the geography of hope. He sought a new dream of the earth, and it is now up to all of us to honour his memory by endeavouring to make that dream a reality.