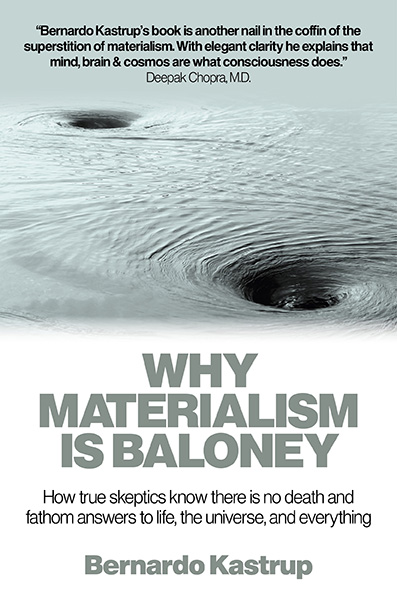

The following is excerpted from Why Materialism Is Baloney: How True Skeptics Know There Is No Death and Fathom Answers to Life, the Universe, and Everything.

Throughout this book I hhttps://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1782793623/ref=as_li_qf_asin_il_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=realitysand0a-20&creative=9325&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=1782793623&linkId=617d13986aa819eaa7497381c004ec88ave endeavored to convey my ideas through metaphors. Indeed, metaphors are powerful tools to paint subtle, complex and nuanced mental landscapes that are difficult or even impossible to communicate literally. While literal descriptions seek to characterize an idea directly, metaphors do it indirectly, by borrowing an essential, underlying meaning from another known idea or mental landscape. For instance, I sought to characterize mind by borrowing the essential, underlying meaning of the imagery of vibrating membranes.

Metaphors use disposable vehicles – in this case, the imagery of a vibrating membrane – to describe a new idea gestalt. The vehicle itself is not to be taken literally: mind, of course, is not literally a vibrating membrane. It is only the essential, underlying meaning surrounding the imagery of a vibrating membrane that is useful to characterize mind. Once this essential meaning is conveyed, one must discard the vehicle as if it were disposable packaging, lest it outlive its usefulness and turn into an intellectual entrapment.

The vehicle of the metaphor may have literal existence: vibrating membranes do seem to exist literally. Yet, that is not needed or even important. Passages from many fantasy books and films are routinely used as powerful metaphorical vehicles, even though they do not have any literal existence. For instance, I could have alluded to the 2010 Hollywood film Inception to metaphorically illustrate my idealist view that reality is a shared dream. This metaphor would have been a powerful one, as you will probably acknowledge if you’ve watched the film. Yet, Inception was 100% fiction and the events it portrayed never had literal existence. The literal existence of the metaphorical vehicle is unimportant for the evocative power of the metaphor.

With this as background, I invite you now to join me on a little thought experiment. Since the eye that sees cannot see itself directly, mind can never understand itself literally. A literal – that is, direct – apprehension of the nature of existence is fundamentally impossible, this being the perennial cosmic itch. The vibrations of mind – that is, experiences – can never directly reveal the underlying nature of the medium that vibrates, in the same way that one cannot see a guitar string merely by hearing the sounds it produces when plucked. Yet, the vibrations of mind do embody and reflect the intrinsic potentialities of their underlying medium, in the same way that valid inferences can be made about the length and composition of a guitar string purely from the sound it produces. The sound of a vibrating medium is a metaphor for the medium’s essential, underlying nature. The medium obviously isn’t the sound, but its essence is indeed indirectly reflected in the sound it produces.

As such, consensus reality is nothing but a metaphor for the fundamental nature of mind. Nothing – no thing, event, process or phenomenon – is literally true, but an evocative vehicle. As we’ve seen above, not only is this sufficient for mind to capture its own essential meaning, it means that only this essential meaning is ultimately true. Everything else is just packaging: disposable vehicles to evoke the underlying essence of mind. The plethora of phenomena we call nature and civilization holds no more reality than a theatrical play. They serve a purpose as carriers, but they are not essential in and by themselves. ‘All the world’s a stage, / And all the men and women merely players,’ said Shakespeare.[1]

A metaphorical world isn’t a less real place; on the contrary! It is a world where only essential meanings are ultimately true. It is a world of pure significance and pure essence. It is a world where there is no frivolity, where nothing is ‘just so.’ All phenomena are suggesting something about the nature of mind. Understanding this allows one to peel off the cover of dullness preventing us from developing a closer, richer, and more mature relationship with life. It forces us to try and absorb the underlying meaning of each development, each day, and each encounter. Life becomes pungent. The cosmic metaphor is unfolding before us at all times. What is it trying to say? A job loss, a new romantic relationship, a sudden illness, a promotion, the death of a pet, a major personal success, a friend in need… What is the underlying meaning of it all in the context of our lives? What are all these events saying about our true selves? These are the questions that we must constantly confront in a metaphorical world.

We must look upon life in the same way that many people look upon their nightly dreams: when they wake up, they don’t attribute literal truth to the dream they just had. To do so would be tantamount to closing one’s eyes to what the dream was trying to convey. Instead, they ask themselves: ‘what did it really mean?’ They know that the dream wasn’t a direct representation of its meaning, but a subtle metaphorical suggestion of something else. And so may waking reality be. As such, it is this ineffable something else that – I believe – we must try to find in life. Do you see what I am trying to say?

In a metaphorical world, all the images of consensus reality are symbols, not literal realities. Goethe knew this, for he wrote in Faust:

‘All that doth pass away

Is but a symbol;’[2]

What in life doesn’t pass away? What in life isn’t transitory? Goethe went on to say:

‘The indescribable

Here is it done;’[3]

Yes. The indescribable is done – or reveals itself – through the transitory symbols of life. Think of the self-embracing double helix of DNA; the magical collapse of dualities during the sexual act; the melting away of parts of ourselves in the form of tears; the mysterious doorway of the eyes; the life-giving self-sacrifice of breastfeeding; the Faustian power of technology; the strange split of empirical experience into five different senses; the miracle of birth and the finality of death. What does it all mean? What are these images trying to evoke underneath their pedestrian literal appearances? They aren’t ‘just so’ phenomena but, instead, represent something ineffable; something that cannot be conveyed in any other way but through the metaphor we call our everyday reality.

We cannot be told what it all means. We must live it and somehow ‘get it.’ There is no other way. We must pay attention to how these symbols get woven together in the mental narrative we call life. Therein, concluded Henry Corbin from his study of ancient Persian traditions, lies the ultimate meaning of it all. He wrote: ‘To come into this world … means … to pass into the plane of existence which in relation to [Paradise] is merely a metaphoric existence. … Thus coming into this world has meaning only with a view to leading that which is metaphoric back to true being.’[4]

Perhaps Lao-tzu, over 2500 years ago, put it best in his description of the Dao, which might as well be a description of the membrane of mind:

‘There is something formless yet complete

That existed before heaven and earth.

How still! How empty!

Dependent on nothing, unchanging,

All pervading, unfailing.

One may think of it as the mother of all things under heaven.

I do not know its name,

But I call it “Meaning.”’[5]

Hong Zicheng made it clear where the meaning of the Dao can be seen and how it relates to mind. He wrote, in the 16th century: ‘The chirping of birds and twittering of insects are all murmurings of the mind. The brilliance of flowers and colors of grasses are none other than the patterns of the Dao.’[6]

Clearly, we once knew with intuitive clarity that which we can no longer remember. In today’s culture we take the package for the content, the vehicle for the precious cargo. We attribute reality to physical phenomena while taking their meanings to be inconsequential fantasies. By extricating ‘reality’ from mind, materialism has sent the significance of nature into exile. With the pathetic grin of hubris stamped on our foolish faces, we carefully unwrap the package and then proceed to throw away its contents while proudly storing the empty box on the altar of our ontology. What a huge stash of empty boxes have we accumulated! Idols of stupidity they are; public reminders of a state of affairs that would be hilarious if it weren’t tragic.

The meaning of it all is unfolding right under our noses, all the time, but we can’t see it. We don’t pay any attention. We were taught from childhood to avert our gaze, lest we be considered fools. So now we seem to live in some kind of collective trance, lost in a daze the likes of which have probably never before been witnessed in history. We feel the gaping emptiness and meaninglessness of our condition in the depths of our psyches. But, like a desperate man thrashing about in quicksand, our reactions only make things worse: we chase more fictitious goals and accumulate more fictitious stuff, precisely the things that distract us further from watching what is really happening. And, when we finally realize the senselessness of such reactions, we turn to ‘gurus’ doling out pill-form answers instead of paying attention to life, the only authentic teacher, who is constantly speaking to us. There is no literal shortcut to whatever it is that the metaphor of life is trying to convey. There is no literal truth. The meaning of it all cannot be communicated directly. There are no secret answers spelled out in words in some rare old book. The metaphor is the only way to the answers, if only we have patience and pay attention. Look around: what is life trying to say?

[1] Quoted from Act 2, Scene 7, of William Shakespeare’s play As You Like It.

[2] Goethe, J. W. (author) and Bernays, L. J. (translator) (1839). Goethe’s Faust, Part II. London: Sampson Low, p. 207. Italics are mine.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Cheetham, T. (2012). All the World an Icon: Henry Corbin and the angelic function of beings. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, p. 59. Italics are mine.

[5] Jung, C. G. (1985). Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. London: Routledge, p. 97. Italics are mine. The translation used by Jung is slightly changed to account for Richard Wilhelm’s reading of the term ‘Dao’ (which is often also spelled ‘Tao’).

[6] Zicheng, H. (author), Aitken, R. (translator), and Kwok, D. W. Y. (translator) (2006). Vegetable Roots Discourse: Wisdom from Ming China on Life and Living: The Caigentan. Berkeley, CA: Shoemaker & Hoard, p. 105. Italics are mine.

Main photo by David O’Hare, courtesy of Creative Commons licensing.