One comes away from Barry Miles’s recent biography of William S. Burroughs with an impression of tremendous fear. Not that the book frightens one; I mean that Burroughs harbored a lot of fear. Why is it, for example, that an elderly gent preparing for his regular evening stroll in a small Kansas college town in the early 1990s would, as a matter of routine, arm himself with a pistol, a blade, and a particularly potent formula of mace? It appears, from this and other scenes throughout his life, that his basic posture was of at all times anticipating some vicious attack on his person. In fact, he was engaged in a life-long war against authoritarian structures, what he called “control.”

Fear didn’t come across in normal social interaction. (I saw him on and off starting in 1978.) The impression was of great intelligence and focus, and a basic shyness hiding behind an unreadable expression and old-fashioned gentlemanly manners. There was kindness and generosity in him, too. This was one classy dude. So what’s with the weapons?

When James [Grauerholz, William’s secretary] once broached the subject and asked him [about his need for guns] “. . .are you afraid of something?” Bill grew quite angry and emphatic: “Yes! I’m terrified of everything! Don’t you understand?” (Miles 612)

The need for self-protection started early. Years of psychotherapy, hypnotherapy (which was ineffectual) and narcotherapy (employing laughing gas and sodium pentothal) pointed to early traumas such as being blown as an infant by his nanny (“Nursy”) and later witnessing the disposal, by said nanny, of her miscarried fetus in the basement incinerator of the family home. He also recalled that Nursy had threatened to cut off his penis, and there were memories of having been made to blow the nanny’s boyfriend and of witnessing sex between Nursy and her girlfriend. This perhaps begins to explain how, in his authorial cosmology, women would come to figure as “the Sex Enemy” or “Venusian agents,” parasitic aliens whose vampirism keeps males from their “natural uncorrupted state.”

A note of good old Freudian context may be helpful here. Having your genitals caressed by your nanny would not itself be traumatic. It would be pleasant. The trauma comes in later, when society teaches you that such a thing is really, really bad. Uncle Ziggy taught that we suffer from reminiscences – in many cases, it’s not the actual early-childhood experience that wounds, it’s the way it is remembered, where the memory of it runs up against the subsequently-acquired culture of shame. This dissonance generates the crippling loop Freud called “neurosis.” For Burroughs, neurosis became synonymous with control. Release from control, “clearing” of psychic knots (which led him to study trance states, psychic phenomena, Egyptian and Mayan cosmologies, Ismaili Islam, Buddhism, demonology, and Scientology, and to research and drink ayahuasca), became his mission in art and life. He’s looking for an explanation of some fundamental paradox, while at the same time making art that says paradox is all there is, a paradox within a paradox, courtesy of the classic wicked nanny.

Paradox as a source of mental illness figures in the work of Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing, whom Burroughs knew in London. It’s the so-called “double-bind” theory of schizophrenia. A child can accept a simple contradictory message from an elder. So, for example, “eat your bananas” followed by “don’t eat bananas” is a little screwy, but not crazy making. What tips the subject toward psychosis is a second level of paradox, “who said anything about bananas?” In William’s case that might have been, I’m going to suck your cock, I’m going to cut off your cock, your cock was never addressed.”

Being a homosexual male growing up in the 1930s who is sent to a small, isolated, and exclusive private boys’ school run by a pedophile, where the routine included regularly-scheduled examinations of the naked boys by the headmaster, enriched the mix. That the school grounds, located in Los Alamos New Mexico, soon became the site for the development of the atomic bomb took perversion to the level of apocalypse. (Burroughs used to say that democracy died at Hiroshima – nobody asked him if we should nuke the Japanese.) Is it any wonder that decades later he’s writing scenes about getting hung by the neck while engaging in anal sex and thereby coming into a new incarnation?

Estrangement: You are given for your daily care to a servant who is an alien (the Welsh nanny). Mother, who is supposed to be the source of your identity (your primary object cathexis in Freudian terms), is someone you see at dinner or encounter accidentally in the garden. This is the set up. You are strange because woman is utterly alien. This is, in Burroughsian terms, the set where women become extra-terrestrial vampires.

What does it take to get to this psychic setting? Mother, who is remembered as saintly, beautiful, and unreachable, has handed you off to a female servant who is remembered as a source of comfort and pleasure and at the same time as a witch, crude and nightmarishly perverted. Father is remote, virtually absent, authority in the abstract. Relationships are crippled as a matter of norm. At one point, the adolescent William, while on a visit to the family pile, goes down to the kitchen in the middle of the night to raid the fridge. There he finds his father doing the same thing. The father mouths some words of greeting and is met by a withering stare. Bill remembered this with great sadness, seeing his father wilt in humiliation before him where there should have been a simple moment of bonding between father and son. He regretted that for the rest of his life.

At 18, you get to Harvard, where being the heretofore-privileged grandson of a successful St. Louis inventor makes you a mere second-generation, mid-western nouveau riche, a virtual outcast. Then you go to Vienna and enter medical school but have to run away from the Nazis. The world has gone mad from the start. Over and over, one does not fit, so the career imperative becomes to combat the criteria of fitness, the mechanism of control. This is where he sets out on the path that makes him a prophet of the postmodern, i.e., he anticipated structuralism’s investigation of the determinative role of language in shaping psyche and society and its analysis of the mechanics of coercion.

He was at the same time a prophet of the millennial generation, where economic and emotional circumstances make the child dependent upon the parental purse/apron strings into middle age. Burroughs collected a monthly “allowance” (not a trust fund payment) until he was 50. It is telling in this context that a late novel treats of a kind of utopia organized by incest. Burroughs said in an interview that incest was the ideal family relation. Freud said the incest taboo was the basis of culture. Culture for Burroughs largely meant control. Where there are no taboos there is freedom. He inhabits/generates the “interzone” between incest and alienation. Don’t we all? Is it going too far or too obvious to relate this to his themes of weapons, violence, transgressive sex, and death?

After Vienna he goes from St. Louis to Chicago where he works as an exterminator for a time, then enlists in the army but pulls family strings to get out (with an honorable discharge on psychiatric grounds) when he realizes they won’t make him an officer. He lands in New York.

In New York, in the fall of 1943, William naturally moves toward Columbia University (he had taken a psychology course there in 1937) where he meets Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Edie Parker and Joan Vollmer, the women who host this outsider set in their off-campus digs. Carr was the mixer, the one who connected them all. (Carr’s Times obituary in 2005 called him the midwife of the Beat generation.)

The initial Columbia connection of ’43-44 was David Kammerer, an old friend of Bill’s from school days in St. Louis, who had moved to New York to stalk Lucien Carr. This is perhaps the strangest thing of all at this point in the story. Kammerer had been a teacher and scout master who became obsessed with Lucien when the latter was a fourteen-year-old boy scout. When Lou went to college, David quit his teaching gig in St. Louis to follow the boy. This happened several times, as Lucien moved from one college to another, David would follow. After Lucien attempted suicide while enrolled at the University of Chicago, his mother, who was relocating to New York, sent Lou to Columbia. David then took a job as a janitor in a Manhattan apartment building. Finally, in an early a.m. showdown in Riverside Park on August 13, 1944, David demanded that Lou submit to a blow job and Lou stabbed David with his pocket knife, loaded David’s clothes with rocks, and pushed his corpse out into the Hudson River. Kerouac helped Lou dispose of the evidence (the knife and David’s eyeglasses) but Burroughs, older and wiser, told him to turn himself in and plead self defense. The cops didn’t believe Carr until the Coast Guard found the body some days after the fact.

Up to this point Carr, though the youngest of the group, had been the main instigator. When he went into juvenile detention as a murder convict, Burroughs took over leadership, becoming their mentor in matters literary. He loaned the others books and he and Kerouac began collaborating on stories, though William didn’t think much of Jack’s talent. The group had a habit of acting out what they called “routines,” little comedic scenes where they played various roles – the criminal and the cop, the countess and the rube, that sort of thing. This eventually became the basis of Burroughs’s writerly method. His novels were constructed out of a series of routines, often based on his dreams.

Meanwhile, Bill got into junk. He had been trying to supplement his allowance by dealing in stolen military goods–a machine gun and some morphine. The drug came in the form of an ampule with a small needle attached, single doses that were ready to inject in case of emergency. One of his buyers, an addict, suggested he try shooting one. Bill got hooked and stayed hooked, with some periods of abstinence, for the rest of his eighty-three years.

After the murder of Kammerer, Jack married Edie Parker (so her parents would bail him out of jail where he was being held as a material witness) and they moved to Michigan. Bill took up with Edie’s roommate Joan Vollmer. Bill was gay, but he and Joan had a strong intellectual and emotional bond, and they became lovers. Addiction was a problem for them both. Bill used junk and Joan was addicted to speed. Bill was busted in 1946 for forging prescriptions and when he was ordered by a judge to return to St. Louis for the summer as a condition of probation, Joan was left alone with no money and a roaring speed habit that gave her hallucinations and finally got her hospitalized for amphetamine psychosis. Getting out of New York looked like a solution to substance abuse problems, so William cooked up a scheme whereby he would, with his family’s help, buy land in Texas and become a farmer.

During his time away from the city, William had hooked up with an old college friend, Kells Elvins, who invited Bill to partner with him in a cotton-growing business in Texas. William did this until he heard from Ginsberg that Joan had been committed to the mental ward. He decided to go rescue Joan and bring her to Texas, where they would set up as farmers on their own. The smart move might have been to go into cotton again with his friend, but William decided instead to settle on a remote piece of land surrounded by forest to farm marijuana that he could grow quickly and sell for immediate profit.

Bill got off junk, but doubled up on the booze (a pattern he would repeat throughout his life). Joan continued to use speed, which at the time was available without prescription as a kind of sinus remedy. “Bennies,” or benzedrine, came in an inhaler inside of which were strips of paper soaked in the drug. The illicit user would break open the inhaler and drop the paper in a cup of coffee or some other drink, or roll up the paper and swallow it. All of the Beat group used bennies. At one point Kerouac had to be hospitalized for phlebitis from long hours of sitting typing under the influence of speed. (At the time, many artists and scientists used the drug to fuel long work sessions. The poet W. H. Auden, for example, was a user, as was computer pioneer Norbert Weiner.) But Joan’s use was constant and the friends were all concerned about her.

The Texas pot scheme was not a success; Bill failed to cure the weed and had to sell at a loss. Also the couple had gotten in trouble with the sheriff (a law man with a statewide reputation for corruption and murder) for stopping their car to have sex by the side of the road. It was time to move.

They tried New Orleans for a while, until William got busted for junk use. Apart from issues of drug possession, in Louisiana, merely being a junky was a crime that carried a year sentence. Bill got arrested for having needle marks on his arms, and the cops found guns and a jar of weed in the house. Bill’s parents bailed him out and sent him to rehab, but any further trouble would get him a stiff prison sentence. It was time to move again, so they skipped town prior to the trial date. After a brief stay with their friends in Texas to sell their property, they left the country, settling in Mexico City.

William enrolled in the university to pursue his interest in Mayan archaeology; this also provided a renewable student visa and got him a student stipend under the G.I. Bill. Drugs (and boys) were cheap and easy to come by and he and Joan continued to drink heavily and use drugs. Then one day in 1951, during a drunken party, Bill attempted to shoot a glass off the head of his wife, William Tell style, and the bullet entered her skull. She died in the hospital.

Various explanations have been put forth: It’s a drunken fool with a gun; it’s a suicidal impulse on the part of the wife who egged him on; it’s his feeling humiliated by Joan’s cutting insults in the presence of the boy he was courting at the time; it’s demonic possession.

Once again William’s family bailed him out, and they may have bribed officials to keep him out pending trial. His case dragged on through multiple postponements over fourteen months, then his attorney fled the country after a boy he shot during a road rage incident died. Bill too fled, first to his family in Florida, then to South America in search of ayahuasca, then to New York for four months and a painfully unsuccessful affair with Allen, and finally to Morocco, where he took up residence in Tangier.

In Tangier there was a sizeable expat community of gay men. Food, rent, drugs, booze, and boys were cheap, and Bill developed the heaviest junk habit of his life. He began to accumulate material for what he titled Interzone, later Naked Lunch, immediately. The term “Interzone” has a couple of important vectors of association. Tangier was then officially an “International Zone,” jointly administered by eight nations. There were separate judicial systems. A British citizen was not subject to the French or Moroccan courts, for example. Interzone also implies a kind of world-in-between. This is the “set,” the mental space in which the routines that came to make up Naked Lunch took place.

In Tangier, Burroughs’s junk habit became so bad that he began to fall apart, moving in to the worst possible lodgings, ceasing to bathe, etc. People, he later said, would avoid him in the street. His family finally intervened, sending him to London to take a cure. Newly energized in recovery, he returned to Tangier and to the writing project with gusto, fueling his long daily sessions of writing with majoun, a readily available, potent hashish confection that produced the requisite waking dream states. Absent junk, his sex drive returned, and his long-term affair with one boy, Kiki, gave him the idea of the body of the lover as a kind of orgone generator, which appears in Naked Lunch and remains as a theme in the later work. “Orgone” is a term coined by the controversial psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich to indicate the vital energy of life, which Reich associated with orgasm, and which could be stored up or drained off by various circumstances. Reich invented the “orgone accumulator,” a structure sort of like an outhouse in which the subject could sit to soak up orgone. Burroughs, a lifelong follower of Reich, had such a box built in several of his quarters over the decades.

Burroughs wrote to Ginsberg that he was contemplating writing some account of Joan’s death, the memory of which haunted and horrified him. He later said that Joan’s death had given him no choice but to write his way out. He’d had an interest in psychic phenomena ever since his nanny introduced him to Welsh magic, and he came to believe that he was possessed by a demon which his friend and collaborator Brion Gysin called “the Ugly Spirit.”

Bill and Brion had been experimenting with trance states, and during one such session Brion said “the Ugly Spirit killed Joan because.” Bill seized on this. Obviously it deflected blame away from himself and onto something over which he had no control. The Ugly Spirit brought into focus the whole issue of control that was becoming central to his work. He came to believe that the demon was a kind of culminating manifestation of everything that is evil about human civilization, particularly American civilization. He associated it with the Rockefellers, all politics, the police, the whole mechanics of control. Language, he saw, was the means of control, so language, writing, would become his weapon in the struggle.

His first novel, Junkie, later Junky, published in 1953 by Ace Books, a publisher of detective and “true crime” pulp, is a fictionalized account of his experience as a heroin addict in New York city in the 1940s. A second autobiographical project, Queer, which he worked on in Mexico after Joan’s death, remained unpublished until 1985. His breakthrough came with Naked Lunch, published in Paris in 1959 and the U.S. in 1962.

The book is innovative in form. Burroughs has said that the chapters could be read in any order. This was perhaps partly the result of the way the book was put together. Ginsberg and Kerouac visited Bill in Tangier in early 1957 and found his room littered with pages of typescript. They sequenced the pages and Kerouac retyped the whole thing, correcting typos and spelling mistakes and working in Bill’s hand-written edits to make a presentable manuscript. Bill then took the last chapter and made it the first chapter, and that became the book. Again, the novel is autobiographical, a series of routines that follows addict William Lee from the U.S. to Mexico to Tangier. (William Lee had been the pen name Burroughs had assumed for the publication of Junkie.)

The title was the result of a misreading by Ginsberg of “naked lust.” Burroughs liked the result and kept it. He later commented that “the title means exactly what the words say: naked lunch, a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” Burroughs elsewhere refers to “the long newspaper spoon,” the idea of the press as part of the control culture “feeding” control/language to the public. The three-year delay in publishing the American edition was due to the publisher’s anticipating a court battle over censorship. Grove Press was engaged in several court proceedings over its banned books and held off on Naked Lunch until the prior cases were resolved. Naked Lunch was one of the last literary works to be engaged in legal action challenging obscenity laws. Ginsberg said “it broke the back of literary censorship in the U.S.”

Naked Lunch established the method that Burroughs would use for the rest of his working life and its somewhat random sequence anticipated an important new technique that would occupy him for several books, that of the “cut up.”

Brion Gysin, whose primary practice was in visual art, had been cutting up some materials and had placed layers of newspapers beneath to protect the table from the blade. He then discovered that the randomly sliced-up strips of newsprint presented to the visual field some striking combinations of language. He turned Bill on to this and they began experimenting with the method as a way to generate prose. The method fell in line with Bill’s mission of disrupting control. If the primary mechanism of control is language, then disrupting language would combat control. That this anticipated Jacques Derrida’s “deconstruction” and Michel Foucault’s studies of knowledge and power explains why Burroughs was celebrated in French intellectual circles before he was recognized as a major author in America.

Burroughs’s avoidance of the conventional narrative arc harmonizes with the “narratology” work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, for whom conventional narrative endlessly “reinscribes” or retraces the well-worn steps of the status quo. The end of the story is always “the State.” Conventional storytelling operates as a circular path that pretends to progress. It proceeds from the status quo, through breach or crisis in the control apparatus, and then returns to the status quo. Narrative says that daddy lost control for a minute there, but now he’s back in business and we are all a little wiser. The good guy has won. In reality nothing has happened. The urge to freedom, the impulse to throw off control has been channeled through the long newspaper spoon, momentarily placated, and we’re back where we started.

In Burroughs’s work, there’s no daddy, no good guy, no fixed roles, and no resolution. Everyone and everything is in flux, in between, in the Interzone.

Roughly at the time of the writing of Naked Lunch, there were parallel developments in the study of ritual. This would have no doubt interested Burroughs, though I know of no evidence of his consulting the anthropological literature on ritual at this time.

There are two main vectors in the research. One is that in traditional societies, social dissonance is dealt with in a kind of ritual cycle that either restores the cohesion of the group or results in schism and the splitting off of a separate group.

The other vector has to do with performance, for example, music/dance events, where the participants become, for a time, something other than their normal selves. This may involve elements such as costumes, role-playing, trance, or abandon, but need not. The activity of performance produces a degree of flux in the social norm in any case. Victor Turner, whose work addresses this, says that social norms are so overdetermined that after the event, normalcy is almost always restored. But not always. There is the idea that performance pushes the boundaries, enabling incremental changes in the social matrices.

This mode of theory, by extension, proposes that art, literature, music, and dance still fulfill this function. Literature that transgresses normal values may push social change. I will return to this.

According to Miles, when Ginsberg was helping Burroughs to organize the Interzone manuscript that became Naked Lunch, he expressed doubts about the book. He didn’t like it, thought it lacked coherence and would not be understood. The rebel poet didn’t see that lack of closure was the whole point. Reality and perception are fragmentary – it is ideology, the condition of dominance, that “makes sense” of the story. Allen repeated this error, this romantic yearning for ultimate meaning, in the 1970s and 80s in his teaching, where he criticized the new trend in poetry that didn’t put across a clear narrative. I was there; I saw it. Allen thought it lacked heart. The practitioners of the new poetics, like Burroughs two decades ahead of them, saw the coercive element in romantic poetics and purposely troubled meaning as a matter of ethical imperative.

Burroughs’s work also anticipates the Freudian revival that took place largely in the field literary and radical political theory in the 1960s and 70s. It is easy these days to forget that Freud was a doctor, a clinician whose primary mission was to enable his patients to cope within the bounds of European middle-class norms. He did not set out to challenge bourgeois culture in the clinical setting, but he was also a social theorist, and after the war his ideas on repression and neurosis in the larger social milieu began to be applied to political economy and literary theory. Sanity or normalcy depends on the repression of socially unacceptable desires. Developments in linguistics noted that grammatical and narrative structure are social structure, what the Freudian revivalist psychiatrist Jacques Lacan (who as a young psychiatric resident had been Antonin Artaud’s doctor [!]) called “the Law of the Father.” To disrupt language is to break the Law, to rebel against the Father.

In the 1970s-80s, linguist and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva, in works such as Revolution in Poetic Language and Desire in Language, noted that at times of social upheaval or significant historical change, literary language tends to become transgressive in form and content.

Burroughs’s use of “bad language” and his graphic descriptions of violence and sexual deviance are calculated to disrupt repression and control. And of course they did, when the Massachusettes Supreme Court ruled that Naked Lunch did not violate obscentity statutes because it had redeeming social value. The book, along with other banned works fought for by Grove Press, transgressive works by Henry Miller and Jean Genet, did change America. Burroughs was right. Language can triumph over control.

Notes

Barry Miles. Call Me Burroughs. New York: Twelve. 2013

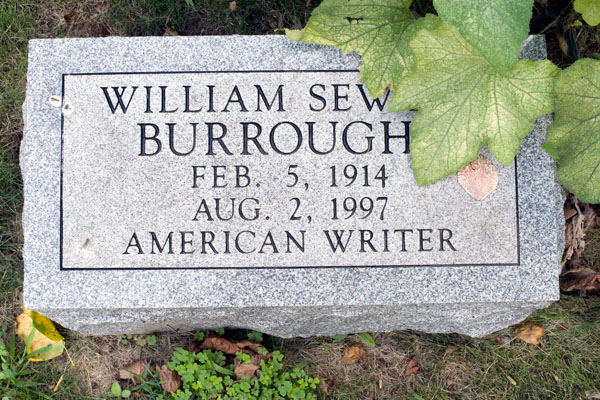

Image by Walter Skold, courtesy of Creative Commons license.