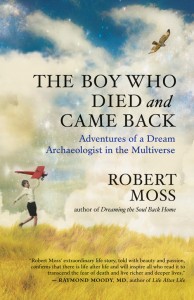

The following is excerpted from The Boy Who Died and Came Back: Adventures of a Dream Archaeologist in the Multiverse published by New World Library.

At nine, I died again. This time I came back remembering not only the whole journey but a whole other life, lived among people other than human in a world that seemed like home.

I will try to reenter this journey, through the gates of memory and desire:

In a suburb of Melbourne, in front of our modest bungalow, I am in shorts and thongs under the hot sun. I am doing what normal boys do, poking an anthill with a stick. The anthill is the size of a tumulus, and its tenants are not meek little leaf-carrying ants, but large and heavily armored bull ants, whose bite is agonizing. For nine-year-old Robert, stirring the bull ants to a war frenzy feels less like bullying than like an act of bravado, especially with the crazy boy from across the street egging me on.

I jab harder, and the ants of the garrison rush out furiously over my feet, nipping and punishing. I jump back, using the stick to brush them off. Next I am doubled over in pain. Could bull ants pack that much poison? Strangely, the pain that crumples me is coming not from my feet but from my lower right abdomen.

I hobble across the burned lawn to the house. My father comes out the front door and looks at me, dog at his heels.

Before he can ask, I say, “Dad, I feel a bit crook.”

Griff, our corgi, whimpers and licks my feet. Dad asks no questions. He runs back in the house and phones for an ambulance. He knows I don’t mention pain unless I am close to breaking. I was in hospital the previous week with pneumonia in both lungs but never complained.

At St. Andrew’s Hospital, the doctors in the emergency ward find that my appendix is about to explode.

“How did it get to this stage?” they want to know. “Robert must have told you he was in pain.”

Dad says, “He doesn’t talk about pain.”

Next, the operating room. They want to take my appendix out right away. They will put me under first, if they can. “Can’t put the little bugger down,” I hear someone say as they double the dose of anesthetics.

I’m still in my body when the knives come out and the blood flows. I have a mild interest as I watch layers of skin and flesh peeled back from somewhere outside this boy’s body. I’m struck by how pale this body is, in a sunburned country. Some of the people in scrubs are gossiping and giggling. Don’t they know I can hear?

I don’t want to see any more. I drift out into the corridor. I see my mother in a waiting room, drawn and deathly white. I don’t want to be present to her grief, knowing that I am the cause. My father sits strong and straight beside her, always the soldier on duty.

I slip by them. Now I am up on a window ledge, looking out through the glass. I see a great bird gliding on straight wings above the rooftops, and envy its freedom.

My face is pressed to the window. The glass yields under my pressure. I push a little, and its texture changes. It becomes a soft bubble, containing my head and shoulders. I butt, and the bubble of soft glass pops open and lets me pass.

I am happy to be flying, like the sea eagles I admired in Queensland. I practice swooping and gliding. I can see white sand and blue water at the city’s edge and the moon along the beach. The moon is the gate of Luna Park, a big, round face with an open mouth that invites you to step through if you dare. “Luna Park, just for fun,” they say in the advertising jingles. I want to go through the moon gate now and ride the roller coaster and the ghost train and look at girls in summer dresses.

Quick as thought, I am at the moon gate. Nobody asks for a ticket. The park seems strangely empty, but that is fine with me. Maybe I’ll go on the ghost train first; I smile, remembering how it spooked my cousin. I jump into a car, and the train rattles off at high speed. We are going down at a steeper angle than I remember. Soon it’s almost a vertical descent. This is scarier than ghosts in sheets and skeletons. I am gripping the edges of the car with both hands, willing myself not to be thrown out. But I can’t keep my hold. I am plummeting down and down, headfirst, through a lightless tunnel.

Dark within dark. It fills my mind. I don’t know how my fall is broken or how I rediscover myself laid out on a bed of soft ferns and grasses, but soon none of that matters because I am surrounded by warmth and love. The people who tend me are very tall and very slender. They bend like flowers. Their skin is silvery and they glow with an inner light that radiates from the center of the chest. I don’t think they are wearing clothes, but this is in no way shocking to me. They hold a bowl to my mouth and encourage me to drink. The juice is delicious; it reminds me of mangoes and passion fruit and wild berries all at once.

They are working on my body. Their fingers are very long and play me like a stringed instrument. I have the sense that they are adjusting my form. I can see my toes growing longer, like theirs, which are as long as their fingers. They are singing over me, and the music brings tears of joy. I know this song, or its sister. I know I am home.

There is no measurement of time in this world, apart from the changing colors of the great Tree of Life at the center of all. There is no division of day and night. We live in a perpetual twilight. I swim and climb and move like a flying fox through the trees with the other young ones. I sit with the elders and grandmothers. They transfer their wisdom by bringing me inside their energy fields, as within a tent, and filling me with their songs and images.

When I grow beyond boyhood, the young women take turns teaching me other things, until the chosen one receives me into the sacred bed. I become a father and a grandfather among these gentle people. Life in a sunburned country as a sickly boy is a fading dream that disturbs me less and less.

I enjoy the body I now inhabit — its quicksilver ability to morph and stretch, to give and receive pleasure. Yet with long use it slows and falters, and I understand that it is time to let it drop, as a well-used garment, and travel on, through a pattern of stars the elders showed me, for which I am now a memory keeper. I choose dissolution by fire. I rise on the sweet aroma of fruitwood burning in the pyre, ready to enter the dance of the stars.

But a force intercedes. I am pulled up through the layers of earth and rock, up into a world of glass and brick and asphalt, and thrown back into the body of a nine-year-old boy with stitches on his abdomen.

His mouth — my mouth — is terribly dry. The people around me look like ghosts. I’m not sure whether I’m among the dead or the living. I feel terribly sad, as if I have lost my home.

“Welcome back.” One of the ghost people is peering into my eyes, which are wounded by the hard sterile lights of this place. “You went away, didn’t you?”

Luna Park. Just for fun.

Photo by Bart Van Leeuwen, courtesy of Creative Commons license.