The following article was originally published on GrahamHancock.com

Standing Up To Those Who Always Take The Largest Portion

For a long while I’d been vaguely aware that there’s something wrong with the collective noun “Sioux” for the confederation of Native North American peoples speaking the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota languages. Then, on 2 December 2016, I meet Cody Two Bears, District Representative for the Cannonball Community on the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council, and finally get the picture clear. “Sioux is just a word that people know us by,” Cody tells me, ‘so I’m not against it. Even if somebody calls me a word that I don’t particularly accept or interpret very well, I just tell them, ‘If that’s how you know us that’s fine’.”

Nonetheless the noun “Sioux” does have a history and does carry baggage. It’s thought to be derived from a pejorative term meaning ‘Little Serpents’ in the language of another Native American people, the Ojibwe, and to have been bastardized into French, with the ‘x’ plural marker, as Nadouessioux. It first appeared in that form in 1640 in the writings of the French-Canadian explorer Jean Nicolet. Later, around 1760, it was abbreviated to Sioux and adopted into the English language. “So,” concedes Cody, “the Sioux name in the history books was given to us by the Wasi’chu, the white people.”

We’ve entered another etymological rabbit hole that runs deep, since it turns out that the Lakota word Wasi’chu does not translate literally as “white people”. What it actually means is “he who takes the fat”, or “he who takes the larger portion” – in other words, a greedy person. “We’ve always called white people that,” Cody explains, “because we see the greed in them a lot of times – the one who takes the larger portion. We see that spirit about them.”

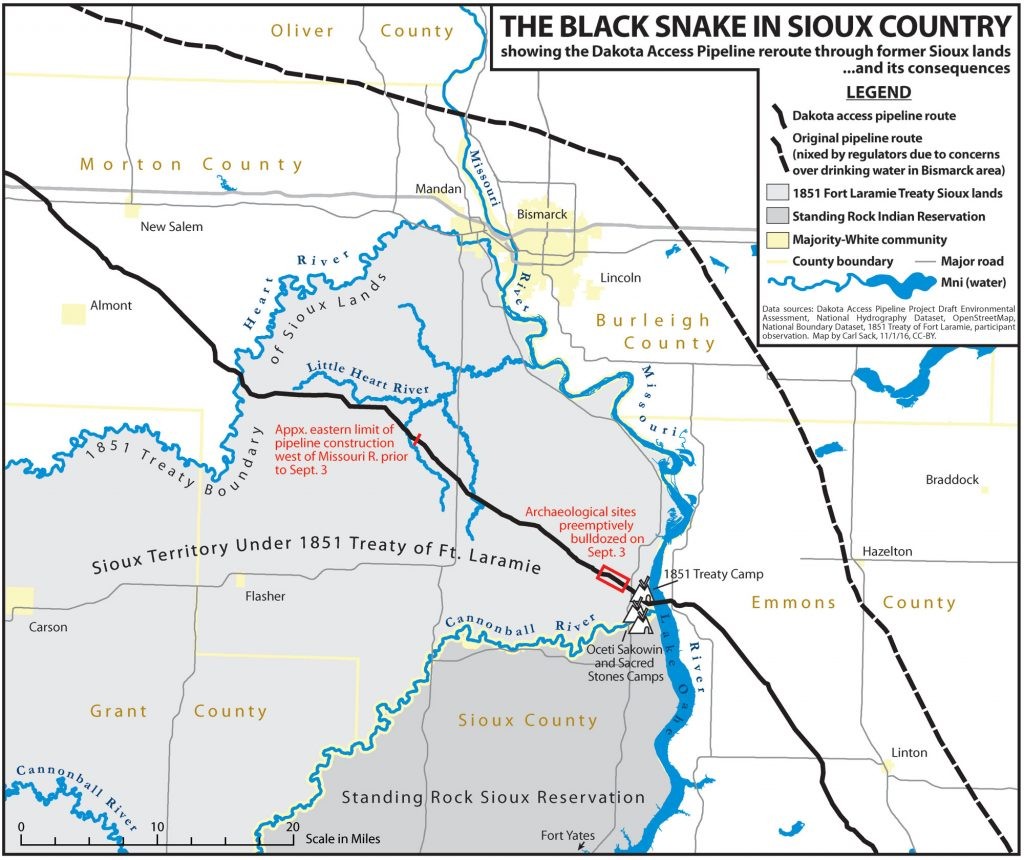

This spirit of greed, and of taking the larger portion – by force or deception or both – is an unmissable presence looming over the sad history of Native American lands usurped by successive governments of the United States of America. The ancient and traditional keepers of the land have again and again found themselves in conflict with industries and agribusinesses hungry for profits and backed by the power and authority of the US government. The most recent battle in this struggle of centuries was joined in 2016 in North Dakota at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, and at the protest camp named Oceti Sakowin situated just beyond the reservation’s present northern boundary. There, from July 2016 and onwards into the winter, a rainbow coalition of Sioux, other Native American tribes, and non-Native American peoples gathered to stop the laying of an oil pipeline under Lake Oahe on the Missouri River half a mile north of Standing Rock in a location that not only transgressed traditionally sacred lands, but also threatened the Reservation’s water supply in the event of a spill.

Such spills happen surprisingly often with oil pipelines, and when they do they can cause immense damage. Indeed on 5 December 2016, more than 175,000 gallons of crude oil leaked from the Bell Fourche Pipeline into Ash Coulee Creek in western North Dakota.i That was just 150 miles north of Oceti Sakowin, proving the point of the protestors that no pipelines are safe or can be guaranteed foolproof against spills.

Oceti Sakowin, by the way, as well as being the name of the protest camp, is also the correct name for the people commonly known as the Sioux. “Oceti means Fire,” Cody Two Bears tells me. “Sakowin means seven – seven council fires. It’s the Seven Bands of our Sioux tribe.”

In this he sees great significance. As well as being the year of the Standing Rock protests, 2016 marked the 140th anniversary of the battle of the Little Bighorn in which General George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Cavalry were famously annihilated by a confederation of Native American tribes led by Chief Gall and Crazy Horse, both of the Lakota Sioux. That was the last occasion, Cody says, when “we gathered our seven bands of Oceti Sakowin together, knowing that there was a fight ahead of us. When we gather in our traditional cultural ways, our leaders would come together and pray and have ceremony and seek guidance from The Creator on how we need to go about our battle with the US Government. What are we going to do to win this? Everybody at that time told us we had overwhelming odds against our people… that we didn’t stand a chance and that we were crazy for trying to go to battle with these people. But we knew that we were guided by The Creator which is the most powerful thing you can have on your side.”

Cody’s point is that this is all happening again now – that in 2016, for the first time in 140 years, the Seven Bands gathered and that, in a curious and ambiguous way, history seems about to repeat itself. “One hundred and forty years ago, and again today, we brought the Treaty Lodge back to our people. We had ceremony before anyone even came. We set up that Council Lodge north of where the Oceti Sakowincamp is today. We set that there before any people came and gathered. We prayed and had ceremonies and asked how are we going to defeat the US Government now… What are we going to do to win this one?”

The immediate issue is the future of the $3.8 billion, 30-inch diameter, Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) which crosses 1,172 miles of North and South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois. The pipeline is intended to carry more than half a million barrels of crude fracked shale oil a day from the Bakken and Three Forks production areas in North Dakota to a giant oil-storage hub in Patoka, Illinois and thence to the US Gulf Coast where more than half the nation’s refining capacity is based. An early proposal called for the pipeline to cross the Missouri north of Bismarck, the state capital, but the route was rejected because possible future oil spills were seen as a threat to Bismarck’s water supply. Instead the more southerly route close to Standing Rock was chosen, despite posing an equally severe threat to the water supply there, presumably on the mistaken assumption that the Sioux would put up less of a fight than the mainly white inhabitants of Bismarck.

Cody confirms the story: “Bismarck didn’t want it. The Governor didn’t want it. City Councils and Commissions and businessmen in Bismarck area didn’t want it. They first said there was a potential risk of contaminating our water, and that would be devastating because it’s a high populated area. Bismarck’s the state capital downstream. So they decided to reroute it. Two months later, they rerouted it a mile north of my community in Cannonball. Standing Rock reservation. They came and saw our people shortly after that. I was there at that meeting. I’m now in my third year of a four-year term, and I was there in that meeting. We told them, ‘NO WE DON’T WANT THIS to cross above our water either.’ This is our original treaty territory land. Even though rightfully it’s unceded area, we have never sold that land, we have never given that land up legally. There may have been Acts of Congress, but legally that land is still ours. And they’re still coming across original treaty territory land, and that’s what we tell people. People today that don’t know the history say it’s not crossing our reservation. Yes it is. That’s our land. That’s where all our sacred sites are along that corridor. That’s where a lot of burial sites – family burial sites – were along this corridor.”

By the time of my visit on 1 and 2 December 2016, more than 90 per cent of DAPL had already been laid along the more southerly route transgressing sacred lands and threatening the Sioux water supply. All of this, moreover, was being done at vast expense despite a warning from the Institute for Energy Economics and Analysis (IEEA) that the project suffers “financial weaknesses” and that the pipeline “may represent a substantial overbuilding of the Bakken region’s oil-transport infrastructure.” The IEEA report adds that:

“DAPL faces a looming financial deadline. The pipeline’s principal backer, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), has conceded in court proceedings that it has a contractual obligation to complete the project by January 1, 2017. If it misses this deadline, companies that have committed long-term to ship oil through the pipeline at 2014 prices have the right to rescind those commitments—and may well exercise that right.”ii

The IEEA report, published in November 2016, further warns that

“ETP will most likely miss this deadline. The company recently informed investors that it would take from 90 to 120 days to complete the pipeline after it receives its necessary easement from the Army Corps of Engineers to cross the Missouri River, which would push completion of the pipeline well past Jan. 1. The broader economic context for the project has changed radically since ETP first proposed it, in 2014. Global oil prices began to collapse just a few months after shippers committed to using DAPL, and market forecasters do not expect prices to regain 2014 levels for at least a decade. As a result, production in the Bakken Shale oil field has fallen for nearly two consecutive years, creating major financial hardships for drillers. Because the economic prospects for Bakken oil producers have dimmed dramatically since early 2014, oil shippers—in the interest of protecting their investors and shareholders—may attempt to renegotiate terms when ETP misses its Jan. 1 deadline, seeking concessions on contracted volumes, prices, or contract duration. Moreover, if oil prices remain low, as projected, Bakken oil production will continue to decline, and existing pipeline and refinery capacity in the Bakken will be more than adequate to handle the region’s oil production. If production continues to fall, DAPL could well become a stranded asset—one that was rushed to completion largely to protect favorable contract terms negotiated in 2014.” iii

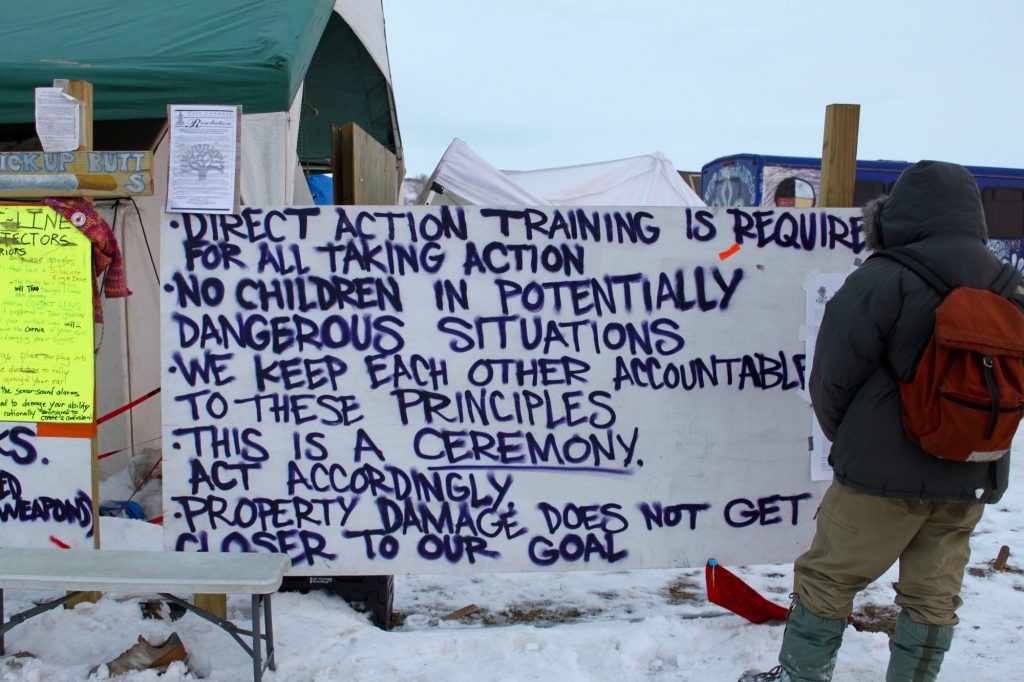

In November 2016 when the IEEA report was published, it was clear that Energy Transfer Partners and other members of the consortium of large corporations behind DAPL remained confident that the project would be completed more or less on deadline – perhaps a little late but not so late as to threaten investors with financial catastrophe. After all, the only holdup was “the necessary easement from the Army Corps of Engineers”, which executives were certain would be granted quickly, for the pipeline to pass through the small embattled sector north of Standing Rock. There, however, in knee-deep snow during my visit in early December 2016, thousands of Oceti Sakowin protestors continued to confront the bulldozers having faced five months of violence in which Mace, tear gas, water canon rubber bullets and attack dogs had been deployed against them by private security services working together with militarised police forces from North Dakota and neighbouring states. During my visit, though there was no overt violence, these heavily armed and armoured para-militaries were highly visible at several points overlooking the camp. Their manoeuvres, and watchful, hostile bearing, seemed deliberately designed to threaten the protestors with further harm. Two days later, however, on 4 December 2016, the US Army Corps of Engineers, which presently has jurisdiction over the lands and waterways immediately north of the Standing Rock Reservation, released a bombshell statement to the media:

The Department of the Army will not approve an easement that would allow the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline to cross under Lake Oahe in North Dakota, the Army’s Assistant Secretary for Civil Works announced today.

Jo-Ellen Darcy said she based her decision on a need to explore alternate routes for the Dakota Access Pipeline crossing. Her office had announced on November 14, 2016 that it was delaying the decision on the easement to allow for discussions with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose reservation lies 0.5 miles south of the proposed crossing. Tribal officials have expressed repeated concerns over the risk that a pipeline rupture or spill could pose to its water supply and treaty rights.

“Although we have had continuing discussion and exchanges of new information with the Standing Rock Sioux and Dakota Access, it’s clear that there’s more work to do,” Darcy said. “The best way to complete that work responsibly and expeditiously is to explore alternate routes for the pipeline crossing.”iv

North Dakota Governor Jack Dalrymple, a DAPL supporter, responded by calling the Army’s decision “a serious mistake” that prolongs a “dangerous situation”.v And writing in the Wall Street Journal, US Representative Kevin Cramer said the decision sent a “very chilling signal” for the future of infrastructure in the United States.” He went on to add, with reference to the Standing Rock protests, that infrastructure will be hard to build, quote: “when criminal behavior is rewarded this way”.vi

Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) and Sunoco Logistics Partners (SXL), two of the leading members of the consortium of corporations building the pipeline, were also outraged and issued a clumsily-worded joint statement in which they described the Army’s decision as

“a purely political action… The White House’s directive today to the Corps for further delay is just the latest in a series of overt and transparent political actions by an administration which has abandoned the rule of law in favor of currying favor with a narrow and extreme political constituency…. ETP and SXL are fully committed to ensuring that this vital project is brought to completion and fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting in and around Lake Oahe. Nothing this Administration has done today changes that in any way.”vii

It is not only the language of the statement that is bizarre but the ideas behind the language. The uncompromising certainty that the project will proceed as planned seems inappropriate in the light of the Army’s decision. And it is downright offensive, indeed sociopathic, to label the Sioux as “a narrow and extreme political constituency” because of their quest to honor sacred lands and to preserve clean and safe water in the Missouri river.

Yet it’s easy to see where such bigotry, such an invincible sense of corporate entitlement, and the notion that exercising the right to protest in a democratic society is somehow “criminal”, might find a receptive audience. I am writing this in December 2016 soon after President elect Donald Trump announced that his nominee for Energy Secretary is to be none other than Rick Perry, a Board Member of Energy Transfer Partners. The President elect himself was until very recently an investor (of “between $500,000 and $1 million”) in ETP whose Chief Executive, Kelcy Warren, donated $170,000 to the Trump election campaign. Trump’s transition team has issued an official briefing stating that the President elect supports the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline – adding that his backing “has nothing to do with his personal investments and everything to do with promoting policies that benefit all Americans”.viii Barring some miraculous change of heart, therefore, it looks certain that the Trump administration will find a way to grant the easement and allow the pipeline to proceed. Indeed, according to some analysts, a rapid Presidential intervention after the swearing-in would mean that oil could begin flowing through DAPL “within the first three months of 2017.ix

Already probable under a Trump Presidency, such an outcome begins to look even more like a foregone conclusion when present events are viewed in their proper context – namely the sustained, brutal and painfully recent history of encroachment and betrayal suffered by the Sioux at the hands of the Wasi’chu. It might be possible to push the timeline further back (to the first contacts between whites and Native Americans for example) but to all extents and purposes this lamentable history – which is still the stuff of today’s news at Standing Rock – begins in 1825 with the first major treaties with tribes of this region. Under these so-called “Friendship Treaties”, the tribes agreed “not to trade with anyone but authorized American citizens” , acknowledged “the supremacy of the United States”, which in turn promised them its protection, and agreed to “the use of United States law to handle injury of American citizens by Indians and vice versa.”x

The next major development was the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty which did notestablish a reservation “but began the process of defining territory” in which the Great Sioux Nation of Lakotas, Dakotas and Nakotas could live and hunt. Under its terms, in exchange for annuities totaling $50,000 a year for fifty years, the tribes “agreed to allow the United States to construct roads and military posts through their country.”.xi

This “first attempt to define the territory of the Great Sioux Nation”, followed the discovery of gold in California in the 1840’s which triggered the eponymous greed of the Wasi’chu. Until then the U.S. government had considered the west a “permanent Indian frontier” – an inhospitable land with little economic value. The gold rush, however, prompted the US to extend its boundaries to the Pacific Ocean and impelled many poor whites from the eastern states to trek across Sioux territory on their way west where they not only transgressed Indian lands but also slaughtered the buffalo herds upon which the Sioux depended for much of their traditional livelihood. A series of confrontations between whites and Indians followed and the whites demanded government protection.xii

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was intended as a response to this demand. When the document was returned to Washington, however, the U.S. Senate refused to give its approval to the long-term financial arrangements, and unilaterally amended the treaty by cutting the appropriation from fifty to just ten years. In this form, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was finally ratified by the U.S. Senate on 24 May 1852, but the amendment was not sent to the tribes until 1853. The government did eventually secure some signatories to the gerrymandered document, in most cases under threat to withhold annuities, but the amendment was never approved by all of the tribes concerned, notably the Sioux,xiii many of whom were not even aware of the treaty’s existence and continued to be affronted by white encroachments upon their lands and traditional hunting grounds, sometimes taking up arms to oppose these encroachments.xiv

In 1861 gold was discovered near the headwaters of the Missouri, making Lakota territories on the west side of the river a target for prospectors. Thereafter matters, from the Indian point of view, continued to go from bad to worse and in 1862 the Santee, a Sioux tribe, began active resistance, attacking a military post and causing large numbers of white settlers to flee. Generals Henry Sibley and Alfred Sully therefore entered Sioux territory in force in 1863 on a punishment mission in which hundreds of Indians were killed.

In November 1863, Sam Brown, a 19-year-old interpreter at Crow Creek, presented the Indian side of Sully’s battle at Whitestone Hill in a letter to his father:

I hope you will not believe all that is said of “Sully’s Successful Expedition” against the Sioux. I don’t think he aught to brag of it at all, because it was, what no decent man would have done, he pitched into their camp and just slaughtered them, worse a great deal than what the Indians did in 1862, hekilled very few men and no hostile ones prisoners…and now he returns saying that we need fear no more, for he has “wiped out all hostile Indians from Dakota.” If he had killed men instead of women & children, then it would have been a success, and the worse of it, they had no hostile intention whatever, the Nebraska Second pitched into them without orders, while the Iowa Sixth were shaking hands with them on the other side, theyeven shot their own men.xv

Continued traffic through Sioux lands transgressed the crucial buffalo ranges in the Powder River area, causing great hardship, and increasingly disrupted the culture and way of life of the people. The Sioux repeatedly objected and demanded government recognition and enforcement of their rights granted under the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. Absent any response, the Indians were left with no choice but to take matters into their own hands and retaliate directly against the trespassers. The US government again sent in the army “to protect non-Indian people, property, and rights-of-way through Dakota-Lakota territory.” The result was 11 years of conflict, commonly referred to as the Plains or Sioux Wars of 1865–1876.xvi

For an overview of what happened next I take the liberty here of quoting at length (sections of text reproduced in italics below are quotations) from teaching materials, created to fulfill the requirements of the North Dakota Studies Curriculum. In these documents, available online at the official portal for the North Dakota state government, some painful historical truths are honestly admitted:

Rather than addressing the issue of trespass in Sioux country, the [US] government responded with talk of yet another treaty with the Sioux. Historically the federal government has had a poor record of honoring treaties negotiated with Indian tribes. As the need for land or resources developed, the federal government simply moved to change the provisions of previous treaties. Treaties are legal documents the United States government, as a sovereign nation, negotiates with another sovereign nation. Initially, treaties with tribal nations sought to define the relationship that existed between the U.S. and a tribe, but as time went on, the U.S. used treaties as a way to extinguish Indian rights to ancestral homelands. And so when Sioux treaty lands were overrun with goldseekers, the U.S. simply sought to modify rather than honor the existing treaty. Tensions along the Bozeman Trail [passing near the sacred domain of the Black Hills and thence through prime buffalo-hunting grounds that had been promised to the Lakota Sioux in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty] continued to escalate.

Then, in 1866, the US government began to build military forts along the Bozeman Trail. This direct violation of the 1851 Treaty was rightly seen as an outrage and further treaty talks ended abruptly. Chief Red Cloud delivered a speech about white betrayal and treachery and led the Sioux delegation north vowing to fight all who invaded their territory as set down in the 1851 Treaty.

Through 1868 Red Cloud and his warriors denied the Bozeman Trail to virtually all incomers.

Army supply trains had to fight their way through, and soldiers were bottled up in their forts. The Indians had little need to negotiate a treaty and so ignored all government overtures to do so. Finally in 1868 the soldiers abandoned their forts along the Bozeman Trail as a way to restart treaty negotiations.

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was the result. This treaty proposed to:

- Set aside a 25 million acre tract of land for the Lakota and Dakota encompassing all the land in South Dakota west of the Missouri River, to be known as the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Permit the Dakota and Lakota to hunt in areas of Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota until the buffalo were gone;

- Provide for an agency, grist mill, and schools to be located on the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Provide for land allotments to be made to individual Indians; and provide clothing, blankets, and rations of food to be distributed to all Dakotas and Lakotas living within the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation.

In return, if the Sioux agreed to be confined to this smaller land area, the federal government would remove all military forts in the Powder River area and prevent non-Indian settlement in their lands. The treaty guaranteed that any changes to this document must be approved by three-quarters of all adult Sioux males. Red Cloud seemed to have won his point since the forts along the Bozeman Trail were abandoned so, in good faith, he signed the treaty. Those Lakota and Dakota who lived south or east along the rivers also signed the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty because they were already living within or near the bounds of the newly established Great Sioux Reservation.

However, three-quarters of the Sioux males did not sign this treaty. Most of the Lakota living north of Bozeman Trail including the Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands, did not sign. In particular, Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa, rejected all overtures to sign this treaty. Sitting Bull soon became a recognized leader of the Sioux who refused to give in to government entreaties to change their lifestyle and live in a confined area…

U.S. federal Indian policy in the 1870s sought to enforce the reservation system and to confine Indians to certain areas apart from settlers; federal policy also encouraged Indians to abandon their nomadic lifestyle in favor of farming. By confining Indians within designated reservation areas, the federal government relentlessly pursued a policy described as “Christianizing and civilizing the savages.” The repugnant goal of this policy was to “make Indians fit to live in the presence of the [white man’s] civilization.” This would be accomplished by replacing Indian spiritual tradition, cultural values, and lifeways with those of mainstream American society. In fact, as a way to encourage Christianization of the Indians, the federal government assigned various religious denominations to administer the reservations beginning in 1869. By 1870 Standing Rock was run by Catholics. The various denominations established schools and generally carried out the “civilizing” policies of the federal government.

Those Lakota living off the reservation in the un-ceded territory complained bitterly when the federal government permitted the Northern Pacific Railroad survey crews into this area in direct violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Sitting Bull opposed this incursion into Lakota lands and interference in Lakota life, and asserted his people’s rights to defend their homelands.

The U.S. government’s response to these complaints of treaty violations was to build more forts to protect settlers and railroad crews. Forts dotted the Missouri River near Indian settlements and treaty lands. Near the Grand River Agency, Forts McKeen and Abraham Lincoln joined Fort Rice along the Missouri River. The federal government continued to openly violate the 1868 Treaty throughout designated Sioux territory.

The most famous and well-documented violation of Sioux rights was the 1874 Black Hills expedition of geologists and soldiers under George Custer, who were sent in by the federal government to explore the Black Hills and report on the extent of gold deposits. The Dakota and Lakota angrily protested the direct violation of the 1868 Treaty. Although the government admitted this expedition was illegal, it justified the survey stating it was only to gain information about mineral wealth in the Black Hills.

Almost at once geological reports of gold in the Black Hills leaked to the general public and a stampede of miners poured into the area. By law these goldseekers were trespassing in areas defined as Sioux country in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Half-hearted attempts by the military to keep miners out of the area were unsuccessful, and by the spring of 1875 the Black Hills were overrun by prospectors. Rather than enforce the 1868 Treaty and remove intruders from the Black Hills as the Dakota and Lakota vehemently demanded, the federal government’s response was to call together a council to again change the terms of the treaty. This time the government proposed to purchase the Black Hills.

The Grand River Agency representatives to this council were highly irritated at the invasion of the Black Hills and initially refused to attend the council meeting. They made their case by saying, “It is no use making treaties when the Great Father [President] will either let white men break them or not have the power to prevent them from doing so.” (John Burke, to E.P. Smith, September 1, 1875, BIA) The Lakota and Dakota bands from all agencies overwhelmingly rejected any proposal to sell or negotiate away their rights to the Black Hills. Tensions between the Indians and government officials were high, but past experience taught the tribes the government would not accept their decision not to negotiate away any more rights or territories.xvii

Here, then, was the background to the Battle of the Little Bighorn, but Custer’s famous defeat 140 years ago did nothing to stop the continuing encroachment on and blatant theft of lands that had been recognized as belonging to the Sioux under the 1851 and 1868 treaties. A major piece of sleight of hand to allow the pretense that all this was “legal” came in the form of an Act of Congress of 1871 which provided “that no treaties shall hereafter be negotiated with any Indian tribe within the United States as an independent nation or people.” From then on, all Indian land secessions were achieved by act of Congress or by Executive Order, thus simplifying, shortening and rendering more convenient to the Wasi’chu, the process of disinheriting Native Americans.xviii

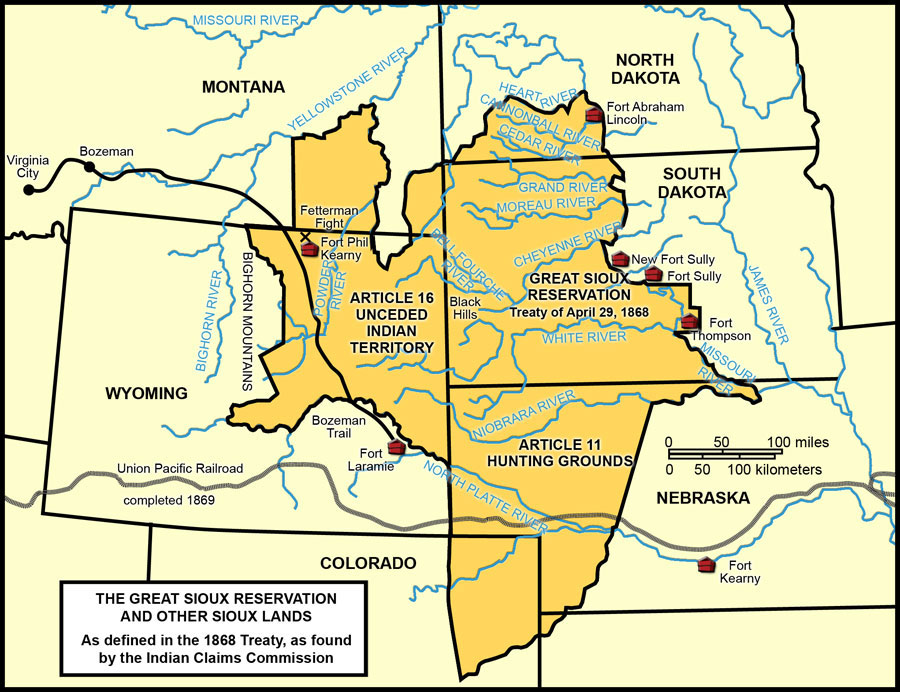

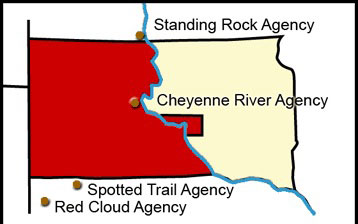

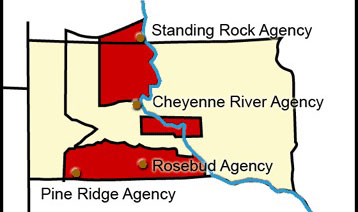

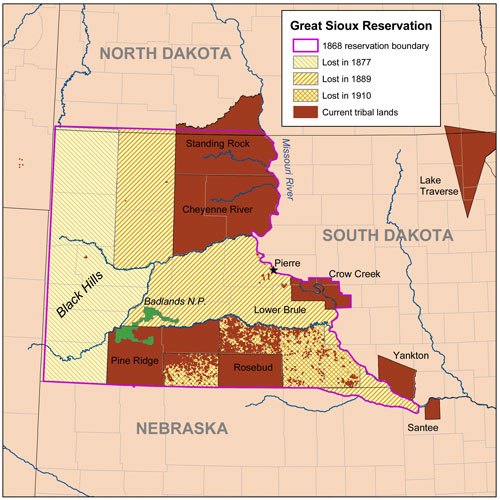

Today, as the maps below show, the original Great Sioux Reservation has been whittled away by such manoeuvres to a tiny rump of its former self:

Further lands totaling around nine million acres that had formerly been part of the Great Sioux Reservation were annexed in 1910 and sold off to white settlers and corporations. The map below details this and other annexations and shows the current extent of the reservations that remain within what was once the Great Sioux Reservation:

Kmusser, CC-BY-SA-2.5

Kmusser, CC-BY-SA-2.5Little wonder then that the Sioux dug their heels in at Standing Rock in 2016. Viewed against the background of almost two centuries of deceit, dispossession and theft, the passage of the pipeline through lands that they had never formally ceded to the US, and across burial places and ancient ceremonial sites of great cultural significance, was simply the last straw.

On my way to Standing Rock, at Denver airport, awaiting our flight to Bismarck, North Dakota, I bump into an old friend of mine – the attorney Daniel Sheehan who defended Professor of Psychiatry John Mack against Harvard University’s attempts to fire him. Despite the fact that Mack had tenure the university wanted him gone because of his unorthodox views on the UFO abduction phenomenon, but with Sheehan defending him Harvard lost the case.

Catching up with Daniel’s news I learn that he’s a founder member of the Water Protectors Legal Collective and regularly volunteers his services to the Sioux at Standing Rock. For my benefit, since I have been trying to understand the treaties and the cavalier way in which they were repeatedly broken, he runs through the sorry history of the “legal” manoeuvres by which the US government has again and again sought to dispossess the people whose rights he’s now committed to fighting for.

“In the 1840’s,” he reminds me, “there was an official map, issued by the United States Government printing office, that had this great big huge shaded area that is the Great Sioux Nation. What happened was that in 1849, when gold was discovered in California, a whole bunch of these private wagon trains were bringing people out to California. They were coming out through the lower part of the tribe’s territory, and they were coming all the way up to the Missouri River, then fording the river and going across lands where the Lakotas reside. It’s primarily the Teton Mountains, the Teton Sioux and the Teton Council power. The seven bands which include the Oglala, which is Crazy Horse’s group, and Sitting Bull’s group which is the Hunkpapa. A lot of those wagon trains were coming through. When they crossed the Missouri River, they had already gone through the territory of the Dakotas and the Nakotas. On the west side of the Missouri River were the hunting grounds for the buffalo. They were killing buffalo and just leaving them to rot, taking the hides and their tongues, leaving the rest to rot. They were destroying the hunting grounds. So the Sioux called a meeting of all seven council members of the Teton Group, all seven bands. They organized a group and went to Washington [DC] and asked the President at that time to stop doing this… to stop ruining their hunting grounds. So the US government agreed to put a fort on the western side of the Missouri River… Fort Laramie… to stop the wagon trains from moving through. But all they really did was protect the wagon trains and the wagon trains continued to do exactly what they had always done.”

We discuss the 1851 treaty and its subsequent amendment by the US government without consultation with the Sioux. Then we move on to the 1868 treaty which, Daniel tells me, “designated all that land west of the Missouri River as belonging to the Lakota”, and promised to honor this commitment “as long as the sun shall shine, as long as the grass shall grow.”

Once again, however, Wasi’chu greed quickly trumped the fine language and sentiments: “In 1874 Custer brought in explorers and mining people to look for gold in the Black Hills. They discovered gold there, so the United States Congress passed a law saying unilaterally we’re going to take your Black Hills… The statute that they used for seizing the land was in complete violation of the Treaty. Then they went on to say that the United States government has the authority to exercise eminent domain in places, so they were going to treat this as though it were an exercise of eminent domain. So they said, ‘How much do you want for it? The Sioux replied: ‘We’re not going to do that. You can’t print out money in your treasury and exchange it for our sacred land.’ To the person, they refused to accept a single penny. So the traditional people, the Lakota and all seven of the bands of the Teton Group say ‘No, that’s our land. We’re not selling it. We’re not going to allow violations right over it. The fact that we don’t go in and kick your ass is just because we’re nice to you. We don’t recognize that title at all’.”

This left an unresolved loose end which continued to worry Wasi’chu commercial interests invested in the unlawfully annexed lands — a loose end that could be tidied up by finding some way to get the Sioux to accept the compensation payment.

The matter came up again in the 1940’s and 1950’s when dams were built on the Missouri River. The purpose of these dams, Sheehan argues, was primarily to “generate hydroelectric power for big corporations.’ But the government position was they would also be giving electric lighting to all the people which allowed them to say there was a public interest issue here thus enabling them to claim eminent domain over land that was still part of the 1868 treaty… So, naturally enough, the Lakota said ‘we’re not accepting that. You don’t have the right to do this. We’re not going to recognize the Title. We’re not going to accept any of the money. So what the government did here is they feathered the money into a raise in the amount of the monthly checks they get, which is allegedly paying them for the land that they took.”

“It’s basically like a thief taking your house,” I comment, “simply by declaring ‘This is mine’ and then justifying the theft by paying you a pittance month by month.”

“Or, another analogy – they come in and kidnap your three kids and say which one do you want back? We’re gonna keep them all. If you say you want any one of them, you’re consenting to us keeping the other two. That’s how they’re doing it.”

“Incredibly sneaky.”

“That’s exactly right! You can see the sneaky lawyers working behind the scenes. They just gave them a raise in their monthly check, hoping they wouldn’t even notice what was really going on. It’s extraordinary. In the United States, there are 3030 counties. Of those 3030, take the 11 poorest counties in the entire United States… 7 of them are on reservations in the State of South Dakota. And this is how they take care of them…”

“Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shore, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles over racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it. Our children are still taught to respect the violence which reduced a red-skinned people of an earlier culture into a few fragmented groups herded into impoverished reservations.”

Sheehan’s further point is that only about half of the lands annexed under eminent domain for hydroelectric projects ended up being flooded, with the other half held under the jurisdiction of the Army Corps of Engineers but not used for any public purpose. It is these lands – illegally acquired, in the view of the Sioux, and illegally retained – that are at the heart of the Standing Rock protests. Arguably since they were never used for a public purpose, eminent domain does not apply and they should be returned to their traditional owners and keepers. Instead, as Daniel puts it, the legendary Wasi’chu drive to take the largest portion led to them being “turned over to a corporation – a private corporation.”

He’s talking about Energy Transfer Partners, Sunoco and the other large financial interests behind the Dakota Access Pipeline and he’s keen to make clear that this, too, is part of a historical process. The 1889 and 1910 acts supposedly opened up Sioux lands for purchase by white homesteaders but in fact, he tells me, “almost all the land was given away to giant agri-business corporations like Ralston-Purina… They were given huge tracts of land by the United States Government. Then they went around and bought more land… the 40-acre-plots that they gave to homesteaders. They would run the homesteaders off and the cattle… they’ve made movies about it like HEAVEN’S GATE…”

“So what is happening today isn’t only about a pipeline. It’s actually about so much more is isn’t it?”

“Number One,” Daniel holds his fingers and begins to count, “not only do you have the issue of the sacred land with the burial grounds and everything, but, number two, you have the issue of the illegality of the seizure of the land with eminent domain. And number three you have the issue of fossil fuel contaminating the water supply. I’ve interviewed these oil guys. When they close out one of these wells, they just cap it, and it’s got this pipe that decays in like 25 years. It rusts out and all the poison that goes in there will just spread into the aquifer. They know it, and they don’t care. They just cap it and leave.

“Then, number four, it goes all the way up to the fact that the instrumentalities of the State are being put behind private corporations – which is fascism. Mussolini wrote all the essays on fascism. Then guys like Henry Lewis who was a fascist, Henry Ford was a fascist, John D. Rockefeller was a fascist. So you have the Federal Government using its instrumentalities, its military and everything else for United Fruit down in South America and with expeditionary forces to take over the Philippines… and so on and so forth… Dole Pineapple… This is a fascist economic system and system of government…”

“And now its putting the power of the state behind Energy Transfer Partners and Sunoco right here in North Dakota?”

“Precisely. So a whole lot of different eddies and currents are swirling around Standing Rock – concentric circles that ripple out from this all the way up now to Trump – who is a complete puppet of the major corporations. He’s going to turn the country into a corporation. He’ll bring in the corporate executives, and subsidize, and lose fifteen per cent or thirty-three per cent of corporate income tax and give them all that money back. We’re gonna cut economic deals, use the power of the government to cut national business deals for the corporations. I mean it’s fascism… out and out fascism. And that becomes obvious here at Standing Rock, because you look at these troops… those are fascist troops. They’re regular brownshirts. Private security companies hired by the Dakota Pipeline are a subsidiary of Blackwater, and DAPL, as you already know is just a front for Energy Transfer Partners and Sunoco, and one of the big financers of the project is Wells Fargo Bank. So we’re targeting Sunoco to get people to demonstrate at Sunoco stations, and we’re targeting branches of Wells Fargo bank as well… People are shutting down their bank accounts, and boycotting Sunoco. They’re going to try to sue people for organizing boycotts against them. We say – go ahead! Do it! See if we care.”

And indeed, after the army’s 4 December 2016 decision not to grant the easement that would have cleared the way for DAPL to proceed, and fully aware that the decision was likely to be reversed by the incoming Trump administration, the Sioux and their non-Native American allies have continued to demonstrate that they are still very much in the fight. In mid-December major protests were held at four separate bank branches in New York City to demand that Wells Fargo, Citibank and TD Bank divest from the pipeline. Said Saige Pourier of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota:

“Our plan here is to shut down Wells Fargo and Citibank. They are the biggest corporations that support the Dakota Access pipeline. And we’re telling them no, to divest. It’s for our future. It’s for our future. Mni Wiconi. Water is sacred. This is life. Without it, nobody can survive. We’re here for our children.”xix

Chase Iron Eyes of the Standing Rock Sioux added:

“We were never the aggressors. All we wanted was peace and to raise our families and to know the power of peace. But we don’t know peace because your money is funding genocide in North Dakota right now. So take a long, hard look and you’ll know why we’re here and why we’re never going away.”xx

The call to divest is being heard far and wide. Also in mid-December, Seattle City Council voted unanimously to discuss legislation that would see the city break ties with Wells Fargo over its financing of the pipeline. In proposing the motion, Council Member Kshama Sawant, spoke about the water protectors at Standing Rock:

“They have withstood blizzards, police repression and attacks from private militarized security forces. They have been bitten by attack dogs, pepper-sprayed, subjected to mass arrests, including for praying. But they have courageously stood strong and shown that when we build organized movements willing to fight, we can win. Elected officials nationwide owe it to the activists to stand with them. One clear way this City Council can do that is by divesting the city of Seattle from Wells Fargo, which also happens to be one of the principal financial backers of the Dakota Access pipeline.”xxi

Minnapolis City Council is reportedly discussing a similar measure and on 12 December activists locked shut the doors of a new Wells Fargo branch in Minneapolis, demanding the bank divest from the pipeline.xxii

Meanwhile at Oceti Sakowin camp, Sioux elders extinguished the seven council fires, which had been burning for months, and young Native water protectors lit a new fire, dubbed the All Nations Fire, as a further symbol of continued resistance. Chase Iron Eyes again:

“There are probably a thousand people still here who are committed to staying until the pipeline is dead. They’re committed to staying to protect our treaty rights and to create a new existence for our people. They’re committed even to protecting American constitutional, civil and human rights. And so we approached the elders, and they told us how to conduct ourselves and to build a new fire. It’s all young people who came out.”xxiii

It’s a point upon which Cody Two Bears elaborates. “This isn’t just about Standing Rock,” he tells me. “This is about everyone. It’s such an important time today – why people need to know this history. Because, for one, the history books would never tell you the correct story… the reason why. I talk to a lot of elders and a lot of spiritual leaders. We had to keep our ceremonies secret. We had to keep our stories a secret for so many years to preserve that. Because the government was fearful of what we had and who we are as a people. The laws will tell you that. There’s even a current standing law today in Montana, I don’t think they’ve taken it out of their law book, that if you see three Native Americans all together then you are able to shoot and kill them. Still legal in Montana, I don’t think they took that out of their law book. Those are the types of laws they created because they don’t want to see Native Americans gather because for some reason they were fearful of us.

“But little do they know, our ceremonies and our ways of life protected us and Unci Maka (Mother Earth). We prayed even for those people who were afraid of us, to help them… to pray for them to make sure they were okay.

“That’s what our ceremonies are based around. It’s not witchcraft… it’s not casting spells on anybody, but that’s what they thought for many many years… For example, the Ghost Dances we used to have in Lakota and Dakota country. When we did that, the Washi’chu were so fearful. They thought we were casting spells, when all-in-all we were trying to keep the balance with the Earth and the Stars. We need to keep that in balance, because if we don’t start doing that today, we’re not going to have anywhere to live in the next hundred years.’

I ask Cody to elaborate and he points to a map of North America on the wall, and to our location on it. ‘There’s a reason why you’re sitting here today and why people have gathered here. This is the center we’re in right now. This is the Heart of Turtle Island… The Black Hills. There’s a reason for that. It’s a ceremonial connection to the Stars. We are Star People. That’s who we are.”

The reference to Star People is intriguing, and I know from prior research that there’s a rich and deep background to it, but Cody won’t say more – deferring to elders responsible for carrying and transmitting the ancient lore who he offers to introduce me to at the proper time. Meanwhile he returns the focus to the present struggle of the Sioux, with their love of land and water, against Wasi’chu interests for whom only money and profit are sacred. “They keep telling me that this pipeline is a national security and national interest issue – that this needs to happen!” Cody exclaims. “And what I tell them is, ‘You know what, you may be right. When you say national security and national interest of this country, we gave three trillion dollars of gold to this country through our people. We gave hydroelectric power. We had to rebuild, lost all our land. WAPA – Western Area Power Association is where they have hydropower down there in South Dakota. They generate $800-$900 million a year through our land. They flooded our people so this national interest can power the whole region – WAPA. We had to do that. Our people had to sacrifice for that. So what we’ve been telling them is we know all about the national interests of this country, but you’re still trying to pick on our people and take what little we have left to preserve for our future generations to come. What little we have left, we have to preserve that now…

“Because there’s a reason why Native American tribes are struggling today. I call it historical trauma from all the atrocities and genocides that happened to our people over the years. The many, many wars that have been waged not just against our tribe, but against every tribe. We’ve had to rebuild so many times! Whatever the government decides they can take, we have to come back from that on our own. We can’t get ahead. Want to see all the historical trauma the children of my people are born with? That’s why you don’t see Native Americans, First Peoples of this land, out there being successful. How come we’re not out there doing great things? We have people coming into this country that all of a sudden are successful overnight. But the First Peoples of this land can’t do that. Why is that? Because we still have a history of that trauma that we carry with us. That’s why you see alcoholism. That’s why you see suicides. That’s why you see health issues arise. Because we are a people still trying to heal. We all know how it feels when we have a death in the family but we have suffered that feeling for five hundred years. And we’re still trying to heal.

“Chief Sitting Bull – love this quote – he thought seven generations ahead to this day, that’s how powerful that man was. He always said, ‘Let’s put our minds together to see what kind of life we can make for our children.’ That’s what he said. But if you think about today and the world we live in, what type of life are we making for them today? I mean, we’re destroying our water, we’re destroying our land, we’re destroying the natural resources of this country… because of greed… because of the one-percenters. Everywhere I go and speak, I tell the people this. It’s just one per cent. We’re the ninety-nine per cent of this country, of this world. Now it’s time to start using what The Creator gave us – our voice.

“Chief Sitting Bull predicted this day… the Seventh Generation. Our youths were the ones that started this movement from Standing Rock. There’s a reason why Obama came here, and then all of a sudden left. That’s not by chance. There’s a reason why that pipeline was put north of our border. There’s a reason why all this is happening, and why there’s a big uproar happening. People are starting to stand together now and move forward to what’s right. It’s happening. It’s scary, but at the same time I keep telling people we’ve been moving in fear for so many years, afraid of that one per cent of this world that controls everything. We were always afraid of them. Today, that’s changed. Today people are not afraid any more, and they know how important our resources are. They understand that we’re fighting for our children now… fighting for the unborn… that’s who we’re fighting for. Chief Sitting Bull knew this was coming. We’ve always trusted that the Seventh Generation is the most powerful, and that we’re going to need change. I never understood that. None of us did. But now you’re starting to see that today, what he was talking about seven generations ago. Very very wise man.”

And this, surely, is the positive and uplifting takeaway from everything that happened at Standing Rock in 2016 – that the generation of today’s youth, this seventhgeneration so evident in all their rainbow colors at Oceti Sakowin camp, have rallied from all over America, and from all over the world, to affirm a fundamental truth – that Wasi’chu is not a skin-color but a lifestyle and a habit of behavior. Habits and lifestyles can be changed. We do not have to be Wasi’chu. We do not have to be amongst those who always take the largest portion and claim it as their right. We can choose to live in the world with love and without fear, not taking from others but seeking to offer nurture and support to all beings.

So, yes, at one level Standing Rock is a Native American struggle with its immediate focus on stopping the wasteful, potentially polluting, historically disrespectful and ultimately superfluous Dakota Access Pipeline. At another level, however, what it is really all about is how human beings wish to live in the twenty-first century.

Do we continue with the existing system, the status quo, the still mainstreamWasi’chu view that does not believe in – and cannot conceive of – spirit, and that regards all of nature as nothing more than raw material to be consumed and exploited for profit by any imaginable means?

Or do we approach the elder peoples, the First Nations of the earth – those whom we have sought to dispossess of their culture, their religion, their lifeways, even of their very names! – and sit at their feet and ask them to help us to create a different system guided by love of the earth and reconnection to spirit?

This is the real promise of Standing Rock – as a catalyst for a worldwide awakening, a worldwide change of consciousness and perhaps even the faint stirrings of a worldwide change of direction.

“The way I feel about this,” Cody says, “there’s a reason why we were all called here. There’s a reason why you guys are here. There’s a reason why non-Natives have come. Different groups, Black Lives Matter, you name it, they’re here. There’s a reason why. It’s because we preserved our culture for so many years. We preserved it and kept it for safekeeping where they tried to get rid of us. They tried to exterminate our people. But we had a Spirit that was so great, and we understood the meaning of protection. That’s why they we call ourselves Water Protectors. It’s true. We are protectors of this Earth. We always have been. That’s why we were the First Peoples here. Because they knew there was going to be a time when more people migrated here and the population grew and was going to overtake the world. So we were given from The Creator a powerful spiritual message that has come today to be preserved for you guys, for everyone. To have these teachings to teach you – the Disconnected Ones – how important this land is.

“So when we see different peoples from all over the world that are called here… I always say follow your heart… and you see people for some reason they’re just aching to be here. I met two individuals from Alaska that are retired, and they just loaded up their car and came down here – they just HAD to be here. What we’re doing today is we are teaching the world how to live. We are teaching the world a culture that has been preserved for everyone. And the more you start to learn, the more you start to understand how important Water is. In our language, Mni Wiconi – Water is Life, and it’s true. Some eighty to eighty-five per cent of our bodies contain water. That’s why, as Native people, we were always a giving people. We were never materialistic. We never really cared about things, about having the finest things, because our culture and ways of life would teach us we don’t need these things and don’t have to have them. Culture is richer than anything.

“When you see people come here, that’s what we’re doing. That’s what this is about now. It’s because we’re teaching people how to live. It’s not just our people, it’s everyone. We need to share our stories now. We need to come out of the box. This was all talked about seven years ago. Our spiritual leaders came together seven years ago, and said we need to start coming out now with our stories. We need to start teaching people our ways of life because that’s the only way we’re going to survive. If this world don’t survive, we don’t survive. So that’s why we’re here. That’s why you guys are here, to learn a way of life that’s going to protect us moving forward. That’s truly why I say we welcome everyone in, because this is not just Standing Rock… not just Native country… this is a worldwide planet issue that we need to change.”

REFERENCES

i http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/dakota-pipeline-protests/it-validates-our-struggle-dakota-access-protesters-nearby-oil-spill-n695191

ii http://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-High-Risk-Financing-Behind-the-Dakota-Access-Pipeline_-NOV-2016.pdf and http://ieefa.org/ieefa-commentary-economic-frailty-rickety-finances-behind-dakota-access-pipeline/

iii http://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-High-Risk-Financing-Behind-the-Dakota-Access-Pipeline_-NOV-2016.pdf and http://ieefa.org/ieefa-commentary-economic-frailty-rickety-finances-behind-dakota-access-pipeline/

ivhttps://www.army.mil/article/179095/army_will_not_grant_easement_for_dakota_access_pipeline_crossing)

vi http://www.wsj.com/articles/what-the-dakota-access-pipeline-is-really-about-1481071218

and

http://kron4.com/2016/12/04/rep-cramer-corps-decision-chilling-signal/

vii http://www.politicususa.com/2016/12/14/etps-response-army-rejection-dapl-easement-most-dickish-most-childish.html

viii https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/dec/02/donald-trump-dakota-access-pipeline-support-investment

ix “Trump Vows Prompt Review of Rejection of Dakota Pipeline”:https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-12-04/u-s-army-corps-of-engineers-denies-dakota-access-pipe-permit)

xihttp://www.ndstudies.org/resources/IndianStudies/threeaffiliated/historical_laws.html

and

http://ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-iii-waves-development-1861-1920/lesson-4-alliances-and-conflicts/topic-2-sitting-bulls-people/section-3-treaties-fort-laramie-1851-1868

xvii http://www.ndstudies.org/resources/IndianStudies/standingrock/1868treaty.htmlandhttp://www.ndstudies.org/resources/IndianStudies/standingrock/historical_gs_reservation.html

xixhttps://www.democracynow.org/2016/12/16/headlines/nyc_water_protectors_disrupt_4_bank_branches_demanding_divestment_from_dakota_pipeline

xxhttps://www.democracynow.org/2016/12/16/headlines/nyc_water_protectors_disrupt_4_bank_branches_demanding_divestment_from_dakota_pipeline

xxihttps://www.democracynow.org/2016/12/13/headlines/seattle_council_to_consider_breaking_ties_with_wells_fargo_over_dakota_access