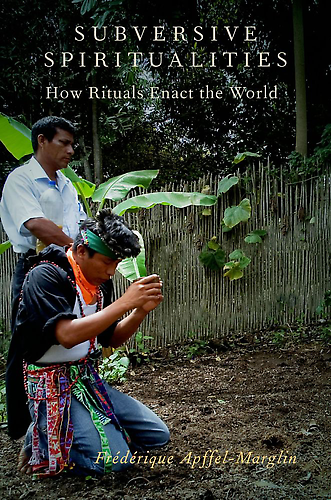

It is a rare occurrence to encounter an anthropological work that is intellectually rigorous and deeply spiritual, one which both illuminates the mind and touches the deep concerns of the heart. Yet when such a miracle occurs, as we find in Frédérique Apffel-Marglin’s Subversive Spiritualities: How Rituals Enact the World all too often these works languish in obscurity. The ethnographical works of Reichel-Dolmatoff on the Tukano Indians, for example, still make for riveting reading, yet his volumes mainly gather dust upon university library bookshelves.

Apffel-Marglin’s Subversive Spiritualities, like Reichel-Dolmatoff’s works, deserves wide reading. After her upbringing in Morocco and her anthropological studies at Brandeis University, Apffel-Marglin began her first fieldwork in the 1980’s in the temple city of Puri, India. Her experiences there opened her eyes to the power of ritual as a regenerative practice, transforming “a secular Western anthropologist into a person with a very different relationship to rituals and to the beings that were invoked and conversed with during their enactment.” As her engagement with ritual deepened over the years, leading her to Peru and extensive fieldwork among Andean and Amazonian peoples, her critique of conventional anthropology, with its view of rituals as mere “symbolic action” and the dismal inverse proportion between anthropological archives and the well being of the worlds these archives represent, sharpened. Eventually she founded Sachamama Center, a non-profit organization in the Peruvian High Amazon which collaborates with the local, indigenous population on bio-cultural regeneration projects.

Subversive Spiritualities is the fruit of her many years of anthropological fieldwork and meditations upon the “cosmocentric economy” of indigenous peoples and the “Modern Constitution” of the West. In it Apffel-Marglin weaves a fugue, a counterpoint of two themes.

In the first, she depicts the richness and efficacy of native practices through first-hand descriptions of the Andean water ritual of Yarqa Aspiy and the agricultural Festival of the Ispallas, as well as native reactions to the forced imposition of the Modern Constitution, as in the well-intentioned Fair Trade movement of Peru or the family planning programs of the Bolivian government. Along the way, she even manages to make fascinating contributions to our understanding of native medicine, and the use of ayahuasca.

In the second, Apffel-Marglin conducts the most comprehensive, deeply informed critique of the foundations of Modernity (laboring under its unwieldy, artificially constructed divisions between observing, alienated self and absolute Space, Time, and Nature) that I have yet to read. In a narrative that reads like good detective fiction, Apffel-Marglin discloses the all-too-human historical and political forces, such as the enclosure movement, witch hunts, and bloody religious wars, which propelled the emergence of modern science. In so doing, she deftly unveils the little carnival showman fiddling his epistemological dials behind the big, booming smokescreen of Oz the Great.

Subversive Spiritualities is, in short, must reading. While authoritative as an anthropological work, it transcends its genre to directly address what are, in the end, the most urgent spiritual issues of our time.