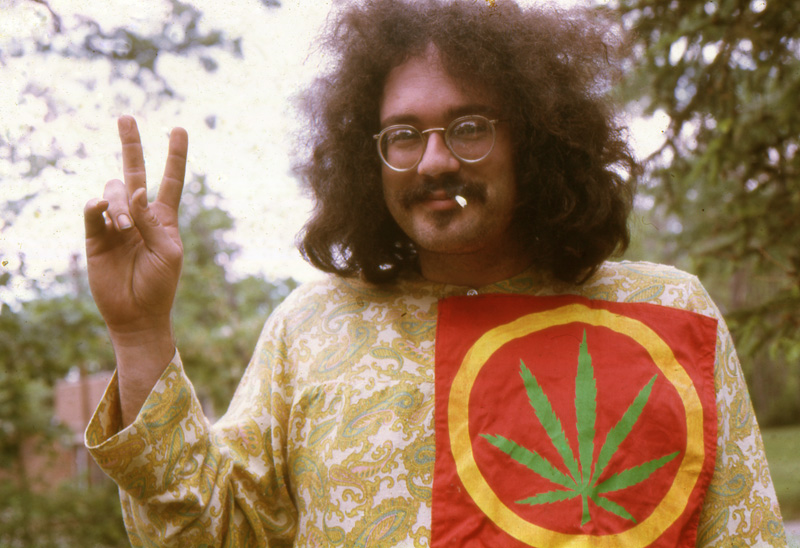

As a kid growing up in Detroit in the 60s and 70s interested in drugs, politics and music, the 6 foot 4, bearded, hairy revolutionary/poet/scholar/archivist/musicologist and self-described “race traitor” figure of John Sinclair loomed large. John is the man behind the MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges, and founder of the White Panther (later the “Rainbow People’s) Party. Their platform: “a total assault on the culture by any means necessary including rock ‘n’ roll dope and fucking in the streets.”

John’s uncompromising life was not without its cost. He was accused of bombing a CIA building in Ann Arbor, MI. He gave two joints to an undercover female police officer ands found himself sentenced to 10 years in prison. John served over two years of that sentence and was only freed after a massive “Free John Sinclair” movement mobilized with the help of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. For a brief moment in the halcyon reform days of the mid to late 70s, it felt like they were winning. John’s case was the beginning of the end of marijuana prohibition in Ann Arbor, which in 1972 passed what became one of the nation’s longest standing decriminalization laws.

But all things change.

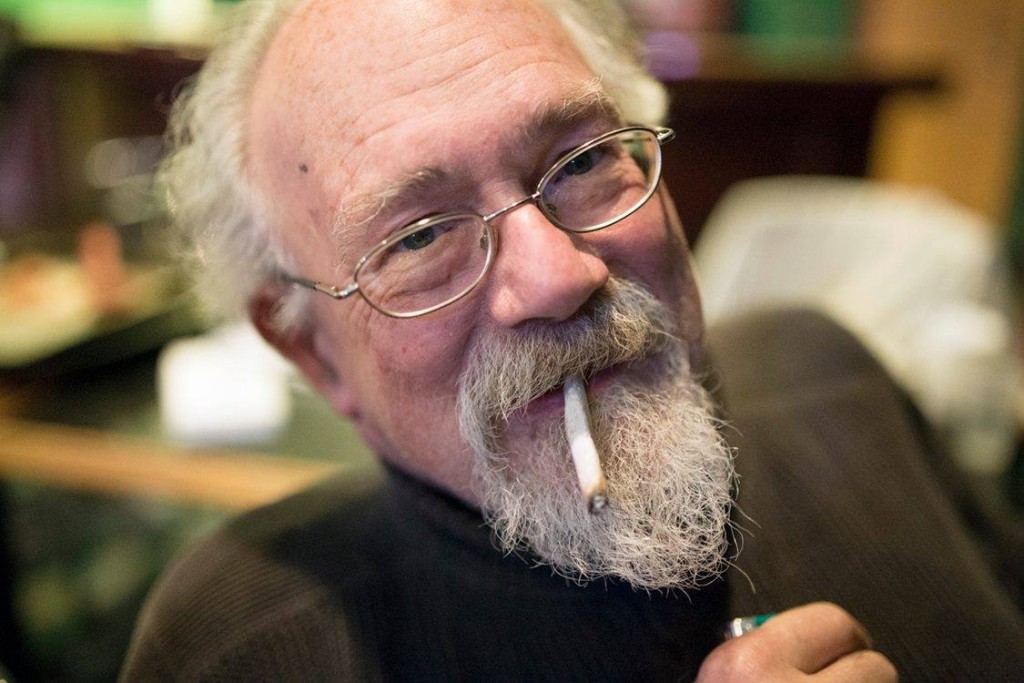

We met 14 years ago while I was licking my wounds from a 20 year heroin habit. We became fast friends, meeting almost daily for coffee or a meal at my brother’s restaurant. We’d do a “beatnik reading of the news” and John would come with his usual stack of papers: The New York Times, The Detroit Free Press. John continues to inspire me as I move into elder status while he still approaches life with the Beatnik ethos mixed in with some Midwest working class. No matter where he is in the world, he finds time to record a weekly podcast. He’s published several books of poetry, and one night I saw him at jazz at Lincoln Center playing to a full auditorium the next night he was in the basement of CBGB’s paying to 20 people. As a senior citizen John continues to live “vow of poverty” with no fixed address, “like a Bodhisattva. “

If you’re smoking a joint that you bought legally, somewhere in the deep credits, John Sinclair was there.

Dimitri Mugianis: How did you go from being a white kid from Davison, Michigan [near Flint] in the late 1950’s to a proto-hippie beatnik self-described race traitor by 1964?

John Sinclair: Just lucky [laughter]. I was talking to someone the other day about these things. I said you know you never could have drawn a trajectory from this kid in Davson Michigan to the leader of the White Panther Party. There is no way to have predicted this. From 1959 to 69.

What was the influence of radio?

Huge. Primary. It is where I got my life. From the radio, black records and music stations. See, when I was a little kid they didn’t have TV yet. That’s how long ago it was [laughing]. You could get a candy bar for 3 cents. [Radio] opened this window into black America which existed nowhere else. There is no other way to get to it, if you were white. There was no way to know anything about it. No way to be exposed to it—it was another planet.

So Davison was all white?

Davison was all white. All of America was fully segregated then. In 1954, when I turned 13, Brown vs. Board of Education [a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional] was decided. Before that [African-Americans] didn’t have the right to education or any parts of the American bullshit. There were Colored drinking fountains. There was a white curtain, you might call it, between white America and Afro America. Not penetrated from either direction.

And then to hear this music that came from the heart of this experience and was about it, it was so great. I didn’t have any idea of what it meant or where it came from or who these people were, but it was the shit. It was greater than anything. So you want to know more about it, me. So that’s how I started. See, in those days, when you got into something that was outside of the mainstream, you really had to work at it. There was the Mainstream and everything else was little rivulets, but they never talked about it, you never knew it existed.

Your granddaughter can get anything by googling it but you had to go out and physically find it, right?

Yeah, you had to find the records. And most of the records I wanted to get, they played on the black stations, and you would have to get it from black people. On Saturdays I used to hitchhike into Flint about 8 miles, going around from one record shop to another, and stealing all the 45s I could get [laughs]

So you would steal from these black-owned stores?

Yes, I was 12, 13, 14. I didn’t have any money [laughs] and I had to have the records. I didn’t care who owned the stores.

You have been an archivist most of your life.

I didn’t have no lofty archival goals. I just had to have the records. If Fats Domino had 25 singles on Imperial Records, somehow I was gonna have every one of those 50 songs.

In the physical act of going somewhere to purchase or steal records you had to physically take yourself in fact into another culture.

Yeah. And eventually they had an opportunity for you to go into the culture itself in a big way. There would be a show at the IMA Auditorium, a big Rhythm & Blues Revue, that you could go to.

Where those shows pretty much segregated?

Oh, yeah, they were all black.

What was it like?

Exhilarating. There would be maybe 20 white kids and we all knew each other, and we danced. See, we danced—see, you dance to this music—we were all fanatical dancers. I was a fantastic dancer as a teenager.

So a white boy who could dance back then got in.

You go to the IMA Auditorium and dance with the colored girls. That was like going to heaven. I was 14, 15 years old and that was like whoa, how did I do this?

Do you remember the first show?

Yeah, It must have been 1955 or early 1956 because I was 14. It was Frankie Lyman & The Teenagers with Bill Haley & The Comets. It was a rare integrated show. So my dad drove me to the IMA so I could see the show and picked me up afterwards.

From the radio and the dance and the music you found yourself at the so-called colored shows?

Yeah, but first you found yourself in a place where you were very happy and comfortable, and you felt great in your body—dancing to this great music, you know.

When did you discover The Beats and that there were other white people that felt the same way as you did?

Oh, way later. For white teenagers then—and probably now—it was very stratified by age. You never knew anyone 2 years older and 2 years younger, and you certainly didn’t know no adults. But you would go to these black dances and there would be people of all ages—grandparents, parents, foxy women in their 20s and 30s rushing the stage trying to tear the clothing off of Jackie Wilson, you know [laughing]. It was just the greatest: all these people—kids, teenagers—teenagers were a minority of the people that were there. Out of the white people—there would be 20 of us and we all knew each other, we all competed with each other over who’s the best dancer. Of course you didn’t have any worries, any bills, driving the parents’ car, you know what I am saying? Gas was 50 cents for the whole night’s gas to drive. You’d get a case of beer for 4.50 including returnables. Different world.

Were you smoking weed at that time?

No, I had never heard of it.

How old were you before you found weed?

Found it? Almost 21, but I read about it when On the Road came out. I was about to turn 16 when On the Road came out in September 1957, and it was a popular book. It opened up this other world altogether of white people that were different and they felt the same way about black people as you did except that they listened to jazz and you didn’t have any idea what that was, but it sounded like the same thing. The thing you never realized about On the Road was that it may have been published in ’57 but it was written in 1952, and it was about 1947. It is really the story of ’46 and ’47. But we read it in the ‘50s, so we thought they were talking about that time. I didn’t know what The Beats were doing until a few years later, when I actually went to New York. There was no way to find out really what it was all about unless you went to New York or San Francisco. That’s where the shit was happening at. You know—New York, San Francisco, L.A., Chicago, they had a few. In Detroit they had 5, you know what I mean?

The Beatnik scene?

Tiny. The whole beatnik generation is about 12 people, and maybe some of their lady friends. You know, there weren’t very many. Kerouac and Ginsburg were roommates in college.

When I went to college two years later, that’s when I got into Kerouac and Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti and became interested in poetry and jazz. I heard jazz for the first time in 1959.

Then you put it all together: Jazz, poetry. Kerouac, Ginsburg. Bird, Coltrane, Miles, it was all the same thing. This is what the beatniks were talking about. No wonder they were talking about it; it is really hip.

In the ‘50s, very much like today, there’s no real way to access true Jazz music in the mainstream culture. And yet 20-30 years earlier, during the war years, it was the popular music of America. Benny Goodman was the Michael Jackson of his time. Then after the war, during the fight over segregation, [black musicians] started R&B on the one hand and modern jazz on the other. Modern jazz surpasses all the old jazz, because it was too smart and had too much going on. ”Niggers on dope” and all that. It became “political.”

This whole thing [racism, segregation] is so awful, man, but by approaching it through the music the black artists present themselves with their noblest face—the best possible representation of black people. Listen to a record by Ray Charles or Muddy Waters, Sam Cooke or Little Walter… these are fucking master works of all time of human history. You listen to that, you can’t think of them as car thieves that you see on your TV. You think of them as geniuses, creators. Then you found out about getting high, and this is where it came from. Well, then you wanted to get high [laughing], and then you did.

See, there is no drugs without jazz, and there is no jazz without Negros. It is all an African America thing.

I think this whole culture is.

Anything good about it came from Black America, but that’s not the wisdom. No one will ever tell you that in today’s world of hipness. They have this whole generation of people they call hipsters who don’t know who Miles Davis was, while he invented hip. It’s like saying you are a Christian without knowing who Jesus was—you know, seriously [laughter]. How can you be a hipster and not know who Lester Young was? They invented hip, these guys, personally, by opposing the mainstream with their own bodies. Jesus Christ. It’s inspirational.

Today’s “hipsters” are just different brands of consumers. They buy a certain outfit, they have the tattoos that they paid big dollars for, they pay $250 for jeans with torn out knees. Our jeans were torn because we couldn’t afford another pair for 10 dollars. The nobility of all this stuff is that black people created this shit out of the most miserable possible American existence. The white people fucked with them in every possible way and never gave them any encouragement.

So what was the influence of drugs at that time? You smoked weed for the first time in 1959?

No, no—in ‘61. I just wanted it so bad, it was like pussy, you know. Finally, you get your first piece of ass, and then that is part of life now, a good part. Drugs didn’t used to be like the way they are.

What do you mean?

Regular people didn’t have any kind of drugs, unless they were prescribed. White people, regular squares. You didn’t find a square with a heroin habit unless they were a doctor or a psychiatrist. Only Negros, Mexicans, jazz musicians, and the others cited by Harry Anslinger used marijuana. “They used it on white women to get some pussy.” That was what was wrong with it, and that is why they created this whole structure against it. Before Jack Kerouac told you how great weed was, you had no idea. And Allen Ginsburg treated it like an everyday normal part of life. Until then you really had to be an outlaw character to be a dope fiend— you had to be a musician, you couldn’t be a regular person. You didn’t know anything about this.

I wonder about when you take out the transgressive and it becomes normative. It also may lose the transcendent qualities.

You mean like today? Marijuana is about to become a strictly consumer product for consumer consumption. The whole production and sales, is turning into a plain capitalistic money-grubbing industry. All the things that made weed what is was to us, they don’t know nothing about that. And then you got these people that are supposed to be the spokespeople for weed, like High Times magazine, who are doing everything they possibly can to hasten the day when it has no meaning other than commercial. Which one is the best? Who made the best? This whole contest mentality.

Like in Ohio, they tried to put in a law that 10 big companies could grow weed and sell it and no one else. The voters turned that down because they didn’t want that. [Corporate control] obliterates the entire culture of weed. The sharing, the turning on, the wanting to enlighten others about things they don’t know about. [Renowned Marxist media analyst] Herbert Marcuse’s concept at the time was that all this [counterculture] will be co-opted. I thought he was totally out of his mind. There is no way you could do that—no way, This is weed, drugs, sex, LSD, rock & roll, the eternal verities. You can’t diminish it, I thought. But how wrong could you be? Like the poet says, “how wrong can a motherfucker be?”

How did you become radicalized? The Beats were never overtly political.

Burroughs once said, it was obvious to the people that run the country that the beatniks were a far greater threat to American civilization than the Communist Party.” Politics is what causes change. The political is an idea of how you address this paradigm of being stuck like a fly in amber, and you have to live there. Do you get high? Isn’t that a political act? If you are not going along with the program, if you don’t get a job, if you don’t cut your hair, you won’t go in the army, isn’t that political?

That was the Hippies. They weren’t consumers, they didn’t have a job, they didn’t want a job, they like to rock & roll, they like to dance, fuck and get high. That’s hippies—all hippies. It was an assault on this whole fuckin’ thing, cause you couldn’t go to war and be a hippie, you couldn’t get a job unless you cut your hair—the whole thing was a confrontation with the standard reality. Every part of it. The content of hippiedom, the content of rhythm & blues, the content of jazz, all of these things were directly opposed to squaredom—directly, in every way. We stumbled into this—there wasn’t any movement, there were just people changing ourselves. Once you started growing your hair long, you could tell who the other ones were. Like Negroes could always tell who the other Negroes were.

You’ve talked about in the early ‘60s anyone with a beard or mustache was….

Any kind of extraordinary facial hair, or longer hair. Until the very end of the 60s, almost all college students were squares.

So then it was a small movement, if it was a movement at all. It is not projected as that. It is projected as this whole youth phenomenon.

No, it was ten years old already before it became [a phenomenon]. At Woodstock all of a sudden they realized there was a million of us. Before that they always described us as an isolated phenomenon. And you were crazy, and your music wasn’t on the charts. Couldn’t get a record contract. [Hippie music] didn’t have a single on the Top 40 until Jefferson Airplane and The Doors in 1967. Before that, it wasn’t even played on the radio. Then young people started taking acid. Acid was the catalyst that exponentially increased the speed of change. All of a sudden in one night you could go through 5 years of personal changes.

And you think acid was…

I know that acid was the catalyst. If you had acid now it would change everything. That is the nature of it—you see through the bullshit.

This is where I am at odds…

This is not your experience with psychedelics? Seeing through the bullshit?

But for me, like with everything, I see the commodification of psychedelics. That is what is happening right now. Basically the approach to psychedelics is the same neoliberal approach as it is to cannabis. They are trying to fit it all into the existing structure.

What you want to do is put the existing structure out of business.

I don’t know if there is a way to do that. Today everyone has jeans and crazy haircuts, and tattoos and shit.

If they can afford it.

Yeah, if they can afford it. And you had said to me a few years ago that the culture has changed so much for the worse. So what is a square and what is hip if everything has been co-opted?

Well there are the eternal verities. Miles Davis is always going to be hip. Always. If the rest of the world is eliminated and there is a Miles Davis record left, it will be the exemplar of hipness—unchangeable. William Burroughs is always going to be hip, Allen Ginsburg will always be hip. If everybody had beards and took their clothes off at parties, it would still be hip.

What seems to have happened is all this shit has been adopted as fashion, as a commodification, and the political component—whether it is an economic or racial political component—has been completely removed.

It is all political now. Now they’re consumers. What could be more political than consumerism? Stripped down: “Put your money up and we will give you a shoddy product for too much money.” That is political. It isn’t just buying something—everything is political in life. That’s what life is about.

So you got the product, and the product becomes the outer appearance—the wacky hair, maybe even the LSD and the cannabis.

Now they want squares to smoke marijuana. They want marijuana to inundate the squares. They want them to buy as much marijuana as they buy Schlitz or Pabst or whatever. They want them to adopt marijuana as their recreational drug of choice.

This is what makes me heartsick—it’s what’s going to put all of my friends out of work.

It’s not all bad, but it isn’t what it started out as. It started out as a way to ween you away from squaredom. You got high, you didn’t see the value of having that new product. And you had acid and you didn’t see the value of having a bank account or even owning a product.

Getting back to what they are doing now, trying to put psychedelicsinto the existing model, into the dominant structures? Isn’t this what the psychedelic movement is about? The biggest psychedelic movement going on right now is the one to bring healing to Veterans and others suffering from PTSD.

This would be good.

Why would it be good?

It would be good for anybody to have hallucinogens.

OK.

Listen,the veterans are the most fucked-over people, worse than blacks. They send these motherfuckers to go kill somebody in their name and then they don’t take any responsibility for them.

You did the time; you are probably the first overt drug war prisoner. Is that correct?

I doubt that. I wasn’t anything, I was a guy that had a bag.

What was your first bust?

My first bust was in October 1964 for selling a guy $10 worth of weed. I did probation for that. I was charged with sales, 20 to life, and I copped to possession and got three years probation.

Jesus.

I was a white college student, and they didn’t have too many of us. So that was the first one. My second bust was a set-up because they still thought I was selling weed, as were all subsequent ones, including the one I am most known for, the 10 years for 2 joints. That time I gave two joints to an undercover policewoman.

What about the whole spiritual thing? The commodification of spirituality and its connection to the psychedelic world?

To me nothing is more removed from spirituality that the spiritual industry. I have no interest in it whatsoever. You are the only guy I know who is really spiritual, who does the stuff that really comes from the heart. I have met a hundred of these motherfuckers and they are all just trying to get some pussy, trying to get some money, try to swell their head, but they have nothing to offer. Spirituality is in here, man {pointing to his heart}. There is no other place to go for it. You gotta go in here. This is where it is. My problem is I have no panacea, I have no solutions, I have nothing but a negative outlook on life. The world today, I think it is just the worst, the end product of apathy and entropy, just going down a big toilet bowl.

Do you see anything in these movements like…

Nothing.

The Burning Man scene? The Occupy scene?

Burning Man, you gotta have 2000 dollars just to get there. I could never go. It is for white people with a lot of money. And the products, the tattoo is for people with money.

What about the movements right now, like the Black Lives Matter movement?

I don’t know nothing about it. I think it is a good thing. The thing that happened in Missouri was a good thing. Took the football team to say we won’t play. Yeah, it’s beautiful but can you image if you translated that into everyday life? Who are the richest black people in America? They could change the whole fucking world. But they never cared about no black people, cause they got theirs. What about Occupy? I thought Occupy was nice, for six months, but what happened to them? Where did that movement go? it just disintegrated into thin air. Are there any signs of it today? I haven’t seen any. There are none in Detroit. There are none in New Orleans.

They started a class conversation.

They started something, and everybody said yes, right. The 1%—they popularized the 1%.

So you have been visiting your young granddaughter.

Yes.

She’s hip, right?

Yeah, she’s a writer.

She is 14, right?

She has developed herself into a completely unique individual. She is completely unique—she’s out there. She got it out of her mind, out of deprivation. No money. You know, she created this thing in her mind. She is out there, man.

What do you see for her? What do you hope for her?

That she just keeps on developing in her own uniqueness. She reminds me so much of when I was 14. You couldn’t get me away from the records and books—I was reading all the time. She is just like me, out there in her own way. She reads, she writes, she is fiendish about music, but not mainstream. I hate her music, but it is what she likes. So it is valid to me. Do what you like, that’s the secret to life.

That is what you guys did though.

We tried.

What’s the legacy?

Oh, I don’t know. It existed. It was great. You can’t erase it; they just don’t tell nobody. There is no legacy. People today don’t know what happened. They don’t know there was a Black Panther Party. They don’t know there was a civil rights revolution. These days they don’t say anything about the Black Nationalist and Independence movements, LSD, they don’t even tell you about rock & roll. I never think about these things—that’s why I enjoy doing interviews. When I talk about it, my thoughts become crystalized, because it’s very rarely that I think about the past.

So what about now, what are you doing now?

I am getting on the plane and flying to Amsterdam. I got a place to stay for the next week, and then I gotta figure it out after that. What am I gonna do? That’s what I have to think about. Where am I gonna sleep? I’m a practicing existentialist.

Break that down for me: What does that mean, an American existentialist?

I don’t care where I am, I am an existentialist wherever I am. I am not working from a framework, from the way things should be. I kind of deal with where I am the best way I can. Without any preconceived notions. When I write a work in verse, it doesn’t have any preconditions. An existential poem, dealing with life lessons that we’ve learned. There’s no cookie-cutter.

To me, the people I looked up to in Detroit…

The existentialists. Negros…

And the Beats, and you, who were out there doing crazy shit. Operating without the net, that doesn’t exist anyways.

Right. Exactly. That’s what LSD gave us, it stripped away all that stuff. All the ways they told us reality was like. And you realized it wasn’t like that. All these constructs, all these things that people made up. One day I was walking down the street and I realized that organized religion was something that white people made up. The regular people, the squares, there wasn’t a God like that. God didn’t tell them all this shit—people made this shit up. Very sick people. I was Catholic, and I had to go to confession.

Man, this shit is all some sick shit, made up by men who wear dresses. They made this shit up, and they are sucking off the choirboys. What does this have to do with me? I don’t have to be bound by any of this foul horseshit. It was a turning point in my life. I’ve never had anything to do with religion after that.

You are 74 now, and you don’t know where you are going to sleep after next week.

A friend of mine, Ben Dronkers, and his son Ravi, they own Sensi Seeds, the seed shop and the Marijuana Hash & Hemp Museum and Museum Gallery in the Red Light District, I will be staying in one of the guest apartments they have above the Seed Bank.

And then you don’t know the week after.

Maybe I will get another week. I am pretty good friends with them. But that’s how I live—I go where I want to, and I do what I want to. I am not beholden to anything, and I can do whatever I want. And I don’t do what I don’t want to do. And to me it is an existentialism in action.

Okay, anything else?

No, it’s good. It works. I have been doing this since 2003.

You have been travelling like that…

Yes, since 2003. My children are grown, I’m not married anymore, I just gotta deal with me, and my requirements aren’t much: I just need a place to sleep and plug in my computer.

You once told me you took the vow of poverty, and you were free.

It’s true. That’s my preachment to young people. You gotta take the vow of poverty. You want to get a career in the arts, creative activities, what have you, outside the mainstream, you gotta take the vow of poverty and realize you ain’t gonna get paid, and then you can do whatever you want. But you aren’t gonna get paid for it. Maybe you have to do something else to get paid.

Do as little of that as possible, in order to keep the time to do the things that you want to do, but you aren’t going to get paid for it—art. Now you can become incredibly lucky, like a tiny percentage of our number, and you can make a living at this. Some get rich—a tiny percent. It’s like having a hit record. I know a lot of talented musicians, but not very many of them have made a hit record. I mean, I know guys who made hit records, but most haven’t. You had a good band. Did you have a hit record?

No.

I had the best rock & roll band of all time, the MC5, and we never had a hit record. Sun Ra made more records than anybody in history, thousands of them, and no one’s ever heard them.

I bought some right from his hand.

With the hand-drawn covers?

Yeah, he had kids scribble on the covers. And in his hand he wrote the name of the songs on the cover.

The secret of Sun Ra’s records was that he had a guy in Brooklyn who had a pressing plant. And he liked Sun Ra, so he would press him 100 records or less—50—of a master {both laugh} It’s the only was he could get his stuff pressed. And he did it so he could hear his own music. He never got paid. It wasn’t until the 1980s when he got paid. So he worked from the ‘50s to the ‘80s before they got paid. I’ve been to Sun Ra’s gigs in New York City where they had more guys in the band than in the audience.

Alright brother, I think we got it.

WHITE PANTHER: The Legacy of John Sinclair from Nomad Cinema (Charles B Shaw) on Vimeo.

Edited by Charles Shaw