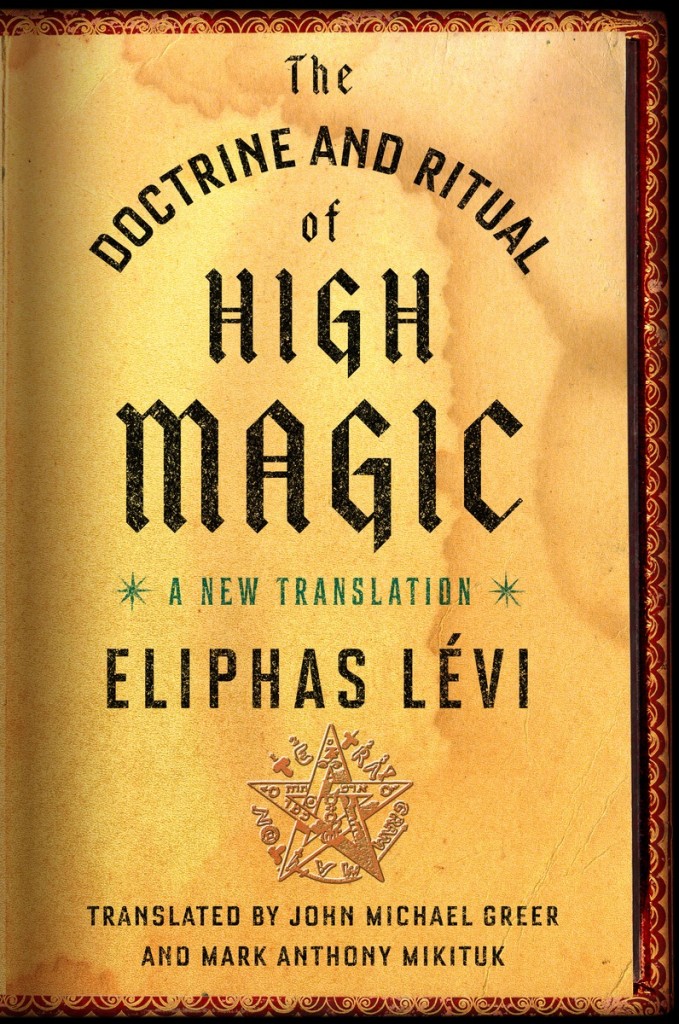

The following article was taken from the introduction to the new translation of Eliphas Lévi’s The Doctrine of Ritual and High Magic, translated by John Michael Greer and Mark Anthony Mikituk, just published by TarcherPerigree.

All things considered, France in the year 1854 hardly seemed propitious for a revival of the ancient traditions of magic. The industrial revolution launched in Britain a century before had leapt the English Channel in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, and transformed France into one of the world’s major economic powers. French scientists were on the cutting edge of scores of rapidly advancing fields of knowledge; railroads and telegraph lines spread rapidly across the French landscape; in the cafés of bustling Paris, members of the comfortable middle class could sit back, sip café au lait, and read up-to-date news reports from the front lines of the Crimean War and the Taiping Rebellion.

To many French people in that year, the world seemed to be marching steadily forward into a new era of progress and modernity, with western Europe in the vanguard of that movement and France, by many measures, out in front of the other European nations. Yet this was the year when a previously obscure French writer, under the pen name Eliphas Lévi, published a book titled Doctrine of High Magic. A sequel, Ritual of High Magic, appeared the next year, and a single-volume edition that included both books saw print a year later. Nor did these publications languish in obscurity. Quite the contrary, The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic brought Lévi immediate fame, and played a key role in kickstarting a revival of magic that remains a significant cultural presence today. Though modern occultism has many sources and streams, a surprisingly large number of them can be traced back to this one work of Lévi’s busy pen.

❧

Eliphas Lévi’s real name was Alphonse Louis Constant. A shoemaker’s son, he was born in Paris in 1810. He was a frail and studious child with strong religious feelings, and his parents encouraged him to study for the Catholic priesthood. His piety and intellectual gifts impressed his teachers to such an extent that once he became a deacon, he was appointed to a teaching position at the Petit Séminaire de Paris, a prestigious Catholic school.

This stroke of luck proved fatal to his career in the church, however. He was assigned to teach the catechism to a class of young women, and promptly fell in love with one of his pupils. While he did not act on the attraction, the experience convinced him that he was not suited for a celibate life, and he left the seminary before being ordained. Thereafter, he supported himself by a variety of odd jobs while making his first efforts toward a career as a writer.

France in the first half of the nineteenth century was wracked by political turmoil, with royalist supporters of the House of Bourbon, imperialist supporters of the heirs of Napoleon, republican proponents of the ideals of the Revolution, and the first wave of modern socialism among the many options in the political smorgasbord of the day. Lévi was thus inevitably drawn into political journalism, and proceeded from there to write his first major work, The Bible of Liberty, which saw print in 1841. The French government then in power found plenty of objectionable material in this manifesto of Christian socialism; it was confiscated by the Paris police an hour after it went on sale, and Constant was arrested. His trial and eleven-month prison sentence, on a charge of inciting insurrection, gave him his first real public exposure.

The years that followed saw Constant leading the ordinary life of an aspiring writer, taking on literary jobs to pay the bills while pursuing his own studies and a diverse range of interests during his off hours. Socialist journalism took up much of his time, but he also put his knowledge of theology and Catholic tradition to good use, penning a Dictionary of Christian Literature that remained in print for many years. In 1846 he married Noémie Cadiot, a talented young sculptor and author, but the marriage proved unsuccessful and they separated in 1853.

By that time Constant’s studies were moving in unexpected directions. He continued writing socialist tracts for a time, but his unsuccessful campaign for a seat in the new National Assembly after the revolution of 1848 proved to be the last hurrah of his activist phase. From that point on, he was on the track of something different—and more profound.

It was in 1853 that he met the most important of his teachers. Joseph-Marie Hoené Wronski was at once one of the most brilliant and one of the most eccentric figures in nineteenth-century France, the inventor of Wronskian determinants and of the caterpillar tread used to this day for tanks and bulldozers. Born in Poland in 1776, he distinguished himself in the Polish cause when that country was conquered by the Russians and Germans. By 1800, along with many other Polish exiles, he was in France, where he devoted himself to abstruse studies for the rest of his life. Occultism was only one of his many interests, but most of his later books focus on it increasingly, expounding an intricate system of thought derived from the Cabala, the ancient Jewish tradition of esoteric philosophy. Constant met Wronski just before the latter’s death, but their brief acquaintance made a profound impact on the younger man.

It was Wronski who showed Constant that magic and alchemy were not merely romantic curiosities, but embodied a philosophy of life and a way of understanding the world that had not lost any of its relevance in the modern, up-to-date culture of the 1850s. That realization transformed Constant’s life. Before long he was devoting all his spare time to occult study and practice—a detail that may have contributed to the failure of his marriage—and assembling the first drafts of the book that would be his masterpiece. To distance this new work from his earlier writing, he adopted a pen name that was simply his own name loosely translated into Hebrew: Eliphas Lévi Zahed, or for short, Eliphas Lévi.

The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic was an immediate success, and in more than a financial sense. Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who was born in 1865 and grew up in a milieu powerfully shaped by Lévi’s influence, reminisced in a 1917 book that in his youth, “one met everywhere young men of letters who talked of magic.” He was not exaggerating; from 1856 until the outbreak of the First World War, occultism was a massive presence not only in French culture but throughout Europe and America, and the revival of magic in those years sowed plenty of seeds that sprouted anew in the occult boom of the 1960s. Many others contributed to the rebirth of occultism, but Lévi was the most important, the one who proved that it was possible to restate the old teachings of magic in modern language and introduce them to a mass market.

Constant’s life after the publication of his famous book was as placid as the years before then had been tempestuous. He lived quietly in Paris, writing and corresponding with an extensive circle of admirers and students. Further books on magic appeared at regular intervals—History of Magic in 1860, The Key to the Greater Mysteries in 1861; Fables and Symbols in 1862, and The Science of Spirits in 1865—all of them developing and restating the insights introduced in The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic. He died in 1875 after a short illness.

❧

The first question that has to be asked and answered about Lévi’s work is this: what exactly does magic have to offer to a world that, at least in theory, has left the Middle Ages behind? We can begin making sense of the answer to that question by sketching out four core themes of Lévi’s approach to magic.

First, living amid the smoking ruins of the eighteenth century’s cult of reason, Lévi rejected the Enlightenment’s blind faith in the omnipotence of the human intellect. The philosophes of the age of Voltaire and Rousseau took it for granted that the replacement of traditional faith with rational understanding would lead to a glorious future of constant improvement, but what they got instead was the chaos of the Revolution, the mass bloodshed of the Terror and the Napoleonic wars, decades of political turmoil, and finally a despotism under Napoleon III that was no improvement on the corrupt autocracy of the Bourbon kings. The blowback of the Enlightenment project led a great many French intellectuals of Lévi’s time to reject rationality and look for salvation in an assortment of deliberately irrational options.

Lévi himself was not among these. His position was far more nuanced. He argued that human understanding was capable of knowing some things about the cosmos, and insisted that where accurate knowledge was possible, facts took precedence over faith. He had no time for the sort of fundamentalism that clings to the literal truth of traditional beliefs in the teeth of the evidence. He pointed out, though, that there are many things that cannot be known by human reason, and that some of these are enormously important.

Faith, for Lévi, begins where reason can go no further. This rule applies just as much to the diehard rationalist skeptic as it does to the devout Christian; after all, the statements “There is a God” and “There is no God” are equally matters of faith. For that matter, the rationalist claim that human beings ought to make choices on the basis of reason isn’t a statement of fact; rather, it is a value judgment, and it rests on a galaxy of usually unexamined preconceptions every bit as resistant to objective proof as the theological claims of the believer.

Since every claim that can be made about the things human beings cannot know is as faith-based as any other, Lévi argued, the sensible course is to choose a faith that does not contradict anything that is known to be true, and appeals to those other human capacities—particularly the esthetic sense and the needs of the heart—with which reason is not well equipped to deal. As a Roman Catholic by birth and training, Lévi found that faith in the Catholic church. His approach to the Catholic church and its teachings, however, had little in common with the sort of rigid literalism that is standard issue in so much of the modern religious scene.

This brings us to the second of Lévi’s four themes. The philosophes of the Enlightenment had argued that Christianity must be nonsense because Christian beliefs, taken in a purely literal sense, contradict known facts about the world. Voltaire’s scornful dismissal of the Catholic church—“Écrasez l’infâme!” (“Smash the wretched thing!”)—drew heavily on the assumption that all religious language must be taken in its most pigheadedly literal sense. Two other writers who influenced Lévi profoundly, Charles-François Dupuis and Constantin François Chasseboeuf, comte de Volney, carried out their own attempted demolition of Christianity on a similar basis; they argued that the narratives central to Christian faith had to be false, because they paralleled mythological narratives in other faiths, particularly those of classical Greek and Roman religion—and they assumed that these must be fatuous nonsense since their literal meanings did not fit the world as known to nineteenth-century science.

Not so fast, said Lévi. Literal meanings are not the only game in town. There are also symbolic meanings, and religions in particular have an extraordinarily long and rich history of using symbols, parables, and other indirect means of expression to communicate their teachings. What is more, religions have an equally long and rich history of using similar means to conceal their teachings from those not yet ready for them. Jesus of Nazareth, he noted, taught the crowds who gathered around him in parables, reserving more straightforward ways of discussing those teachings for his inner circle of apostles. As for Dupuis and Volney, he argued, they had found the most marvelous proofs of Christianity’s relevance and mistaken them for proofs of Christianity’s falsehood—for what does the presence of common symbolic themes in different faiths indicate, if not the presence of common truths shared by those faiths?

To Lévi, in other words, the teachings of Christianity were absurd only if they were taken in a literal sense. The same argument, in his view, applied to every other religion. The literal meaning was the proper spiritual food for children and the ignorant, who stood to benefit from a simple faith that taught basic lessons of morality. The inner meanings were reserved for those adults who had the intellectual and moral capacity to go beyond that simple faith without losing its benefits. In ancient times, the Mysteries had unveiled the hidden truths behind the symbols and fables. Christianity, Lévi argued, had done the same in its early days, but had lost the keys to its own teachings in the last centuries of the Roman world, and thereafter those who preserved the heritage of the Mysteries did so in secret, under the constant threat of exposure and extermination at the hands of the Inquisition and the mob.

The heirs of the Mysteries, though, were supposed to have more than symbolism to pass on to their initiates. Whispered rumors and frantic accusations alike claimed that they also taught and practiced magic. Lévi rejected the notion that magic involved devil worship or supernatural powers; he argued, in fact, that there is nothing supernatural in the literal sense—that is, nothing above or outside of nature. He rejected out of hand the idea that magic could overturn natural laws. If magic is not supernatural, then, what is it, and what can it accomplish?

His answer was as simple as it was revolutionary: magic is a psychological process. The powers that mages invoke exist within their own minds, and the arduous training through which the apprentice becomes an adept is simply a process of learning how to use vivid symbols and symbolic acts energized by the will to draw on capacities of consciousness that most human beings never discover in themselves. The apparent absurdity of many magical rituals is thus beside the point, because any set of actions that have been given a symbolic meaning can be used to accomplish the redirection of the mind that makes magic work.

Consider the reasons why people down through the centuries have turned to magic. Some have used magic because they are poor and want to be rich; some have used it because they are unloved and want to find a willing partner; some have used it because they are weak and want to defend themselves against an enemy, or avenge a wrong done to them, or call down justice on an oppressor; some, more fortunate than the others, have used it because they feel powerless in the face of destiny. All these things can be changed starting from the individual mind. There are many reasons why people are poor, but quite often their own habits play a large role in keeping them in poverty; there are many reasons why people are unloved, and nearly always the most important factor is some detail of their personality that renders them unappealing to potential partners; weakness, in the same way, is as much a matter of attitude as it is of circumstances. Change the habits of thought and action that keep an undesired condition in place, and very often the condition will go away; embrace habits of thought and action that will establish a desired condition, and that condition is likely to appear in short order—“like magic,” as the saying goes.

❧

The three of Lévi’s themes already covered, while not uncontroversial, can be fitted without too much difficulty in the worldview common to Lévi’s age and to ours,. The same thing cannot be said about the fourth and most important theme of Lévi’s work, the astral light.

This is Lévi’s name for a concept familiar to nearly all students of spirituality in one form or another: a subtle medium that bridges the gap between one mind and another, has deep if obscure connections to the sun and the phenomenon of biological life, and can be concentrated, dispersed, and charged with intention by those who know its secrets. The astral light is the prana of the Hindu scriptures, the qi of Chinese tradition, the ruach of Jewish lore, the pneuma of the ancient Gnostics, and the anima mundi of medieval and Renaissance Christianity; the Japanese call it ki, the Arabs ruh, the Yoruba emi, the Iroquois orenda, and the !Kung hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari desert, n:um. This list could be extended almost indefinitely; in fact, around the world and across the centuries, very nearly the only human cultures that have no common name for this medium are the societies of the modern industrial West.

In speaking of the astral light and describing it as the great magical agent, the connecting link that enables magic to reach beyond the boundaries of any one mind, Lévi placed himself squarely in the mainstream of the world’s magical traditions. In the nineteenth century, furthermore, he was not quite as far from current scientific thought as he has since become. The physicists of his time theorized that all forms of energy were vibrations in a subtle substance called ether, which filled the entire universe. Lévi was familiar with the theory and suggested that the astral light might well be an ancient name for the ether, but he did not place any great importance on the identification. His goal was simply to explain the astral light in terms that his readers would find it easy to understand.

The importance of the astral light to Lévi’s teachings is that it allows a psychological interpretation of magic to explain some of the things that magic is traditionally held to be able to do. According to the traditions of folklore and the manuals of magic alike, a magical blessing or curse can affect another person who does not know that the powers of magic have been invoked for his help or damnation. A purely psychological account that accepts modern notions about the absolute dependence of mind on matter, and conceives of thought as a mere side effect of certain lumps of meat called human brains, cannot explain this sort of action at a distance.

The existence of a medium that allows influences to pass from one mind to another takes care of this difficulty. It also solves several other crucial questions raised by any attempt to take traditional magical lore seriously in the modern world. The predictive power of astrology, for example, can readily be explained by a subtle medium that is influenced in complex ways by the angles that the Sun, the Moon, and the planets make with each other in relation to an observer, while other forms of divination can be understood as different modes of sensing the flow of influences through the astral light.

Lévi argues that every thought, word, and action shapes the astral light. Under most conditions, though, these effects have little impact, because they are poorly formulated and sent out into the astral light with little momentum. The more clearly we formulate an intention and the more forcefully we back it up with concentration and will, on the other hand, the more influence it will have on the astral light and the more effectively it will shape the thoughts and actions of other beings. One core aspect of the training of the magician, therefore, centers on learning how to use the imagination and will to define an intentions clearly and project it out into the astral light with as much force as possible. Another consists of learning how not to be influenced by the intentions and imaginations of other beings, in order to have the freedom to act independently.

There is, however, a further dimension of magical training. Under certain conditions, after appropriate training and study, the aspiring magician can enter into a deeper and more fully conscious relation with the astral light, which allows that medium and its influences to be directed at will. The process that leads to this attainment, according to Lévi, is called the Great Work; it is the supreme secret of magic, and Lévi describes it in a galaxy of ways without ever stating in so many words the secret that underlies it.

This reticence is not mere obscurantism. The secret of the Great Work is incommunicable; like falling in love or facing death, it involves a shift in consciousness that cannot be put into words. Thus it cannot be taught to anyone who is not already capable of learning it independently, and each individual who sets out to master the secret has to tread the long road to adeptship alone. The secret can be expressed in symbols for the benefit of those who are almost able to grasp it, and this Lévi does repeatedly, in a galaxy of different ways.

The Garden of Eden and the ancient Greek myths of the Thebaid are among the symbolic narratives he puts to work for this purpose; the Tetragrammaton, the unspeakable four-lettered name of God in Jewish lore, is another; but among the simplest and most profound is a sequence of simple geometrical figures—a circle containing a cross, a six-pointed star formed of two triangles, and a triangle—or, even more simply, the numbers four, two, and three. The circle and the number four relate to the four magical elements, fire, air, water, and earth; the star and the number two relate to the two contending-and-cooperating forces that Chinese philosophy calls Yang and Yin; the triangle and the number three relates to the resolution of those two forces. Unfold the logic uniting these symbols and you have grasped the supreme secret of Lévi’s magic.

❧

The mysteries of the Great Work, and more generally the magical traditions Lévi sought to reintroduce to a civilization that had forgotten them, thus involve practice as well as theory: in Lévi’s own formulation, doctrine is accompanied by ritual. It is entirely possible to approach magical thought as a guide to an unfamiliar way of understanding the world, with no intention of putting that way into practice, and Lévi clearly had that possibility in mind. No small number of writers who came after him followed him along that line of approach.

It is equally clear from the contents of Lévi’s book, though, that he also meant it to be used by readers who were interested in exploring magic not merely as a theoretical possibility, but also as a practical reality in their own lives. That intention was fulfilled abundantly in the decades that followed the publication of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic. The “young men of letters who talked of magic” about whom Yeats reminisced were matched, in intensity and cultural impact if not in number, by men and women who not only talked of magic but practiced it. For a century after Lévi’s death, most practicing mages in the Western world drew extensively on his ideas; read the writings of Dion Fortune, Franz Bardon, Mouni Sadhu, Julius Evola’s UR Group, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, just to cite some or the more widely known names, and references to Lévi and his ideas stand out on every page.

The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic is thus also a magical handbook, and lays out a specific and entirely workable course of training that can be followed by the aspiring mage. A word of caution is in order, however, for those who choose to take up the challenge Lévi offers. Until quite recently, it was standard for authors of magical treatises to go out of their way not to make things too easy for their readers, and Lévi stands squarely in that tradition. Quite the contrary, his goal throughout The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic was to force his readers to think for themselves, to look past the obvious surface meanings of his words to grasp a message that was not meant for the clueless. The tools he put to work in this traditional pastime of mages, though, were those of his own time and culture: above all, the dry wit and calculated absurdity for which nineteenth-century French literature is deservedly famous.

It is thus crucial to keep in mind that Lévi very often uses the same symbolic and allegorical way of speaking he traces out in the Bible, the Thebaid, and so many other sources. It is precisely when he seems to be saying something very straightforward, in the most simplistic of literal senses, that his real meaning is most likely to be concealed. Nor is there only one valid meaning to every phrase or passage. As Lévi himself points out, many magical teachings are meant to be taken in three different senses—physical, intellectual, and spiritual—and commonly the student discovers those meanings one at a time, as work pursued on the basis of one meaning develops the inner capacities needed to understand another meaning.

Those who are interested in practicing Lévi’s magic, and in following his way of initiation, are thus advised to read his book carefully, a sentence at a time, to think about ambiguities and potential double meanings, and to reread it frequently. A piece of advice found in the literature of medieval alchemy is worth following: Lege, lege, lege, relege, ora, labora, ut invenies—“Read, read, read, read again, pray, labor, that you may discover.”

***