We’re on the precipice of a psychedelic renaissance as researchers show the breakthrough clinical results of psychedelic-assisted therapy, where stigmatized drugs like psilocybin and MDMA are used to treat mental health conditions.

However, there’s a looming problem festering in the academic-medical ecosystem of psychedelics — and it’s saliently white. Just as it was in the 1950s, the white lens continues to set the regulations in how we approach, study, test and conduct research, meaning psychedelic-assisted treatments are formed based on studies and trials primarily led by white men to solve white problems.

At dominating psychedelic organizations like MAPS, the majority of clinical trials are centered around white people. From 1993 to 2017, non-Hispanic white participants made up 82.3% of the group across 18 psychedelic studies in clinical trials focused on substances for treating depression, PTSD, anxiety and other conditions. The remaining participants of color were 4.6% Indigenous, 2.5% Black, 2.1% Latino, 1.8% Asian, and 4.6% of mixed race.

It’s clear that causations and treatments of mental illnesses are not a one-size-fits-all approach, as mental illnesses affect individuals in differing destructive ways and at varying severity rates across all ethnic and racial groups. For example, symptoms, triggers and treatments for depression can vary significantly from a Black person to a white, Hispanic, Asian, Indigenous, and so forth. This makes scaling up any mental health services, psychedelic-assisted or not, incredibly nuanced and difficult to understand and treat on both an individual and community level, which is why it’s crucial that racial differences are thoroughly vetted and addressed.

Over the course of several decades, countless studies have revealed that higher rates of psychological distress affect more Blacks than whites, while whites have elevated levels of depression and anxiety symptoms compared to Blacks (Dohrenwend 1969, Vega and Rumbaut 1991). Mental illnesses for Black and Latino communities tend to be more severe and debilitating and often persist for longer periods of time than for other racial groups (Breslau et al. 2005). Participants from the studies also showed that Black groups diagnosed with depression were more likely to remain “chronically or persistently depressed,” experience “more severe symptoms” and “not receive treatment” over white groups.

Race-Based Traumatic Stress

Understanding the complexity of the association between racism and post-traumatic stress disorder, also known as race-based traumatic stress injury, is the driving force behind the essential work of Monnica T. Williams, Ph.D. — a clinical psychologist, researcher, professor, and expert on matters at the intersection of psychedelics, race and mental health.

Race-based stress and trauma is “a natural byproduct of the types of experiences that minorities have to deal with on a regular basis,” explained Williams in an interview with The New York Times.

The current and generational collection of overt, hidden and unconscious forms of racism and ethnic discrimination occur in common settings — educational, social, digital and work — that we navigate daily, inflicting mental and emotional injuries to individuals of color.

Williams recounts the drastic mental health deterioration of one of her patients, an African American woman who encountered racial harassment by a director within her company. She described her as a “high-functioning patient, with two master’s degrees and a job at a company that anyone would recognize.”

“She completely withdrew and was suffering from extreme emotional anxiety,” said Williams. “And that’s what made me say, ‘Wow, we have to focus on this.’”

While most of Williams’ work focuses on the mental trauma of patients who directly experience racial harassment and violence, she also sheds light on how the “long history of pervasive discrimination” in America leads to “vicarious trauma” within the respective racial communities — the murders of George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice to name a few, the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes by 146% amidst COVID-19, the immigration horror stories by Trump’s racialized ICE agency, and the list goes on. Vicarious traumatization is “something that impacts someone many miles away can sometimes impact all of us.”

In the world of psychedelic medicine, there’s an absence of diversity from the top-down: leadership, sponsors, researchers, participants and so on. This mutes the voices and experiences of people of color, where the mental health conditions are metastasizing in racially diverse communities with alarming persistence and severity — especially in Black communities.

Be it with or without psychedelics, we cannot dissect nor inclusively treat mental health illnesses without accessing the psychological effects of racism. This may seem like an impossible feat when the fundamental roots of American history and how we came to be are inherently racist. Still, there is great power in understanding the nuances of pivotal moments and the buildups to them so that we, as a society, can chip away at the wall of stigmas and carve a pathway for real change to one day occur.

Racial Inequalities in Modern Psychedelic Medicine

Wherever seeds of racial inequality have been sown, there are copious layers to comb through to unpack the systemic racism behind why minorities continue to be grossly underrepresented in psychedelic-medicine studies.

The genesis of documented psychiatric research began in the early 1950s by a group of white psychiatrists. Among the group was Humphry Osmond who coined the word “psychedelic” and theorized that hallucinogenic drugs may aid in treating mental illness.

Social and political factors forced Osmond and his peers to terminate their research. The outcome of these pivotal moments further explains why whitewashing continues to prevail in modern psychedelic medicine today, despite the recent celebratory parades of diversity and inclusion loudly made by many American institutions.

Slavery and Hallucinogens: American History in Two Parts

African Americans were still living as slaves 100 years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Black people were enslaved and degraded in every crevice of America’s social stratification throughout the hippie movement and beyond, and are still unjustly being affected today.

At the time, hallucinogens were gaining traction alongside the rise of the hippie era. Sub-genre rock music, psychedelic art and “free love and peace” expressions with brightly colored themes were largely inspired by mind-expanding drugs.

The Political Fall of the Hippie Empire

Born from a collective breaking point of the American people, the hippie movement was fueled by the colossal numbers of death from the Vietnam War. Large protests led by the youth erupted across the nation to revolt against the deranged politics of the war and redefine what it was, at the time, to be American.

The hippie revolution moved politicians to spread a vilified portrayal that drugs were “literally driving American’s youth mad and turning them into violent criminals,” as described by former U.S. Senator Thomas Dodd. Drug users will experience “…loss of feeling of right and wrong…” and “…lead a valueless life, without motivation, without any ambition… they are decultured, lost to society, lost to themselves.”

This fear-invoking message seeped into the minds of the American psyche, playing nicely into America’s racist ideals as Nixon’s War on Drugs campaign began in 1968.

Black Collateral Damage From the Hippie Movement

Nixon deemed two groups as enemies: the antiwar left and Black people, as told by John Ehrlichman, counsel to Nixon and assistant to the president for domestic affairs.

In an exclusive interview with Harper’s Magazine, he said “… by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

The drug war’s ubiquitous influence was designed to place Black people in prison and locked up for a very long time. Reports by NAACP show that there is no difference in drug use rates between African Americans and whites, but evidence shows that the imprisonment rate of Black people is almost six times that of whites.

The lies made by the American government for political gains and the criminalization of Black people during the war on drugs built a longstanding barrier of distrust against the government and government-funded groups within BIPOC communities.

Understanding Racism in the Psychedelic Industry

Ruled by fear and cemented by history, it makes sense on all social contextual fronts as to why the numbers of BIPOC participants and researchers involved with drug-related studies are scarce.

“Because of the criminalization of all these substances and the fallout from the war on drugs, African-Americans face a lot of danger when it comes to using drugs or even talking about them in a way that isn’t true for white people,” explained Williams. “There isn’t a lot of interest in busting white kids who are trying different drugs but the same cannot be said for black kids.”

This double standard also exists for people of color in academia, another race-based stressor that minorities often suffer from. Just 30 years ago, many places across the U.S. denied Black people the opportunity to get Ph.D.s.

“Black people have to be a lot more careful, and particularly those of us, for example, who are clinicians and are licensed,” said Williams. “We can’t really talk in that way about experimenting with these substances.”

The scientific exploration and research of how psychedelic medicine can help treat the race-based stress/trauma and mental health illnesses faced in BIPOC communities have been repudiated for decades.

Dismantling the racial disparity gap in psychedelic research is crucial to the success of scientific studies and trials on psychedelic-assisted treatments that aid mental health illnesses for all people.

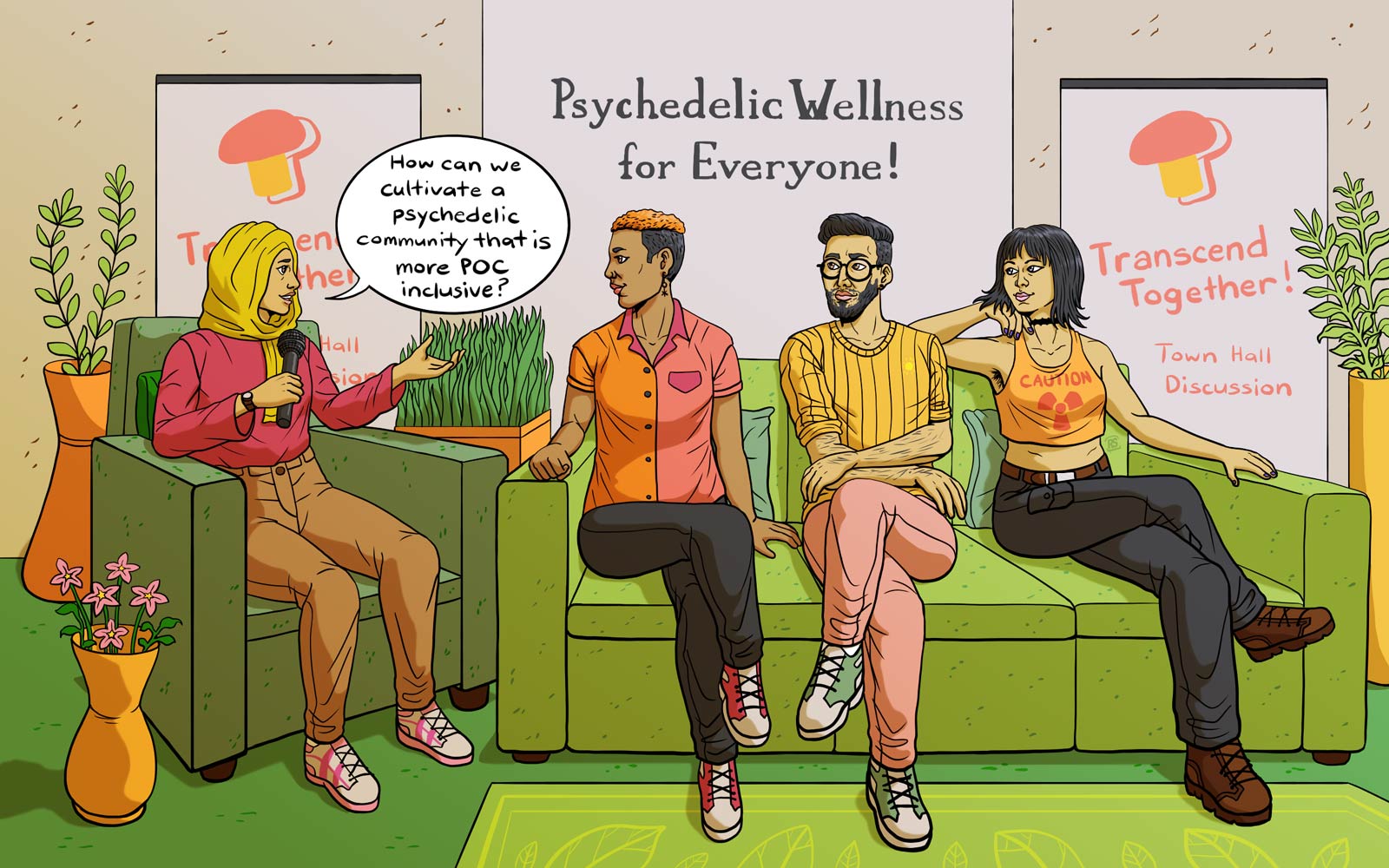

Psychedelic researchers of color like Monnica T. Williams are changing the larger psychedelic-medicine landscape from treating mostly white problems by white people to cultivating a safe environment where future studies and treatments are inclusive of minorities and marginalized individuals on every level.