Is there a point in talking about a counterculture anymore? What is a counterculture, anyway? In a world of disposable content, is a counterculture possible? Or does counterculture depend in fact on that very disposability, such as with graffiti culture?

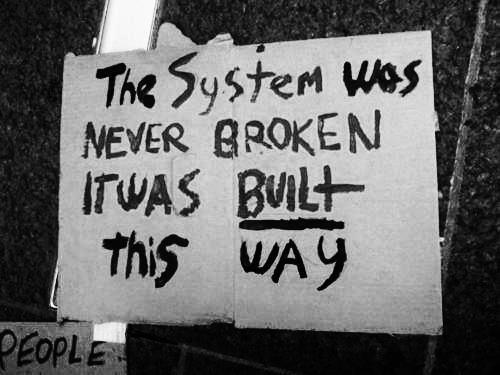

Even by definition, the idea of a counterculture expresses itself as a negation. It is arguable if a counterculture could possibly exist without the myths of the mainstream. As such it is a product of the market, and exists only insofar as it serves a function within that market.

Yet there are ideals which have been part of various vibrant (if short-lived) countercultures, which rest close to the heart of the creative process as structured by the myth of the individual: unfettered self-expression, freedom from the externally imposed social boundaries, irreverent humor, an element of egalitarianism mixed liberally with pirate capitalism, maybe even a sense of pragmatic community. History shows that these ideals are quickly lost in such movements, however, oftentimes as soon as they gain a true pulpit. The largest expression of that in recent history is of course the now somewhat idealized 1960s, a clear view of which has been obscured through a haze of pot-smoke and partisan politics.

However, “counterculture bubbles,” Temporary Autonomous Zones101 and so on are regularly coming into and out of being. Countercultures remain rather toothless in regard to having any capacity to sustain themselves outside the context of the society they stand in opposition to, instead utilizing a self-referential social currency of cool-points, sprinkled liberally with pointless elitism and a side of Who Gives A Fuck? One need merely look at the transformation of musical and sub-cultural genres founded on rebellion: punk, rock and roll, and the like, and what they have transformed into during the decades of their existence. In this domain, the territory between aesthetic, ideals, and social movement becomes blurry at best.

This article is Part 1 of many.

Let’s begin with a quintessential mainstream icon of the branded, shiny counterculture: The Matrix. You’ve all seen it. Even as an example it’s a cliché, and that’s part of my ultimate point. Here’s a framed sketch of the first movie: in the scenes where Keanu Reeves doesn’t seem to be desperately attempting to recall his lines, it is a slick take on the alienation most suburban American youth feel, packaged within the context of the epistemological skepticism Descartes wrestled with in the 17th century. Taken out of the cubicle and into the underworld, we witness the protagonist “keeping it real” by eating mush, donning co-opted fetish fashion, and fighting an army of identical men in business suits in slow motion. The movie superimposes the oligarchic and imperialist powers-that-be in the world over the adolescent’s authority figures. A successful piece of marketing — you can be sure no one collecting profits off of points or licensing deals had any misgivings about “the Man.”

This is not to point an accusatory finger, but rather to show the essential dependence of the counterculture upon the mainstream, because they are not self-sustaining, and every culture produces a counter-culture in its shadow, just as every Self produces an Other. Any counterculture. Punk, underground, beatnik, hippy, psychedelic, straight edge, or occult culture all stand as the cardboard cut-out Shadows of corporate America.

They will be co-opted the moment their shtick becomes profitable. It doesn’t matter that these ideologies have little in common. It is the fashion or mystique that gets sold. When all an ideology really boils down to is an easy to replicate aesthetic, how could they not? “Cool” is what customers pay a premium for, along with the comfort of a world with easy definitions and pre-packaged, harmless rebellions. Psychedelic and straight edge can share the same rack in a store if the store owner can co-brand the fashions, and people can brand themselves “green” through their purchasing power without ever leaving those boxes or worrying about the big picture. Buy nothing day, AdBusters, etc. ad nauseum all utilize this principle. Without laying the material, mythic, and social groundwork for a new society, counterculture cannot be a bridge; it almost invariably leads back to the mainstream, though not necessarily without first making its mark and pushing some new envelope.

Where do we draw the line? As Yogi Bhajan put it, “money is as money does.” The question is how individuals utilize or leverage the potential energy represented by that currency, and what ends it is applied to. Hard nosed books on business such as Drucker’s Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices say exactly the same thing, in a less epigrammatic, Yoda-like way: profit is not a motive, it is a means. Within our present economic paradigm, without profit, nothing happens. Game over.

“Two weeks at Burning Man may be fun, but try doing it for a year and chances are you’ll come back telling me what hell is like.”

Fashion embodies a state of mind, a culture. But it is not that culture. An example of this can be seen in Harley Davidson driving lawyers in their forties. As the company rose to prominence in the 1920s and beyond, Harley Davidson developed its brand off of what they sold, functionally, yet in later years that became a shtick that was re-marketed to people that needed not an alternate form of transportation, but instead what Harley Davidson had come to “mean.” The bottom line here, as discussed previously: we live in a culture where appearances count for a lot more than reality.

“All you read and / Wear or see and / Hear on TV / Is a product / Begging for your / Fatass dirty / Dollar” (Hooker With a Penis, Tool.)

Those who position themselves as extreme radicals within the counter culture framework merely disenfranchise themselves through an act of inept transference, finding anything with a dollar sign on it questionable. To this view, anyone that’s made a red cent off of their work is somehow morally bankrupt. This mentality can only end one way: they will wind up howling after the piece of meat on the end of someone else’s string, working by day for a major corporation, covering their self-loathing at night in tattoos, and body-modifications they can hide. That is, unless they lock themselves in a cave or try to start an agrarian commune.

Growth on its own is never a clear indicator that the underlying ideals of a movement will remain preserved. If history has shown anything, it is that successful movements lose substance either through shallowing their core values until they become an empty, parroted aesthetic, as with most musical scenes and their transition from content to fashion; or the movement’s core values are so emphasized that the meaning within them is lost through literalism, as we can see in the history of the world’s major religions. The early Christian Gnostic traditions of “love thy neighbor,” “all is one,” and the agape orgies were replaced by the Roman Orthodoxy and the authority provided through the ultimate union of State and Religion. The hippies traded in their sandals and beat up VWs for SUVs and overpriced Birkenstocks. It oftentimes seems that succeeding too well can be the greatest curse to befall a movement, and it is a well-documented fact of cultural trends that when the pendulum swings far in one direction, it often turns into its opposite without having the common decency to wait to swing back the other way.

Ultimately, consumers live as shills to various corporate myths because they choose to, implicitly or explicitly, by habit or conscious choice. If your life revolves around how the shoes you wear define you as a person, or which line of body spray is most likely to get you laid, you’ve turned yourself into a patsy. The only way out of this cycle for the consumer is to take control of their choices: to become myth-makers, to create, and forget about trying to be original. People don’t set the artistic trends by trying to set the trends. They are genuine to what gets them in the vitals. Fight long enough and it will find its market, or you will die trying. You only lose if you give up, and let your identity get co-opted because it’s easier that way.

Despite popular opinion, effective marketing is not about outright manipulation. It is about finding a need within the public, focusing it, and fulfilling that need in a way that makes them dependent on you to fulfill it. Yoga was boiled down from a very demanding esoteric practice with a rich and complex ideology behind it into an activity that any housewife can do with a little effort, a mat, and a DVD.106 These housewives were looking for a lifestyle change, a way to stay healthy and feel good. This was provided to them in an effective, albeit diluted, package. They wouldn’t have gotten into the yoga baby-pool if it wasn’t packaged in a way that catered to their needs and beliefs.

Yet, at least at the moment, those more rich and intricate ideologies behind yoga still exist, and they can be sought out. More to the point, though purists can snub such mainstream examples, there’s no sensible argument that the spread of something like yoga into the mainstream is actually a bad thing in any way that matters, especially in a country with dramatically surging obesity statistics.

To take this back to our central theme, countercultures can accomplish a great deal of good as a cultural counterbalance of the mainstream. But this ends at the water’s edge.

If people demand organic products, and have money to invest in that need, companies will meet that demand. Though the proliferation of yoga, organic food, specialty food products, high quality imports, and the like are being supplied to an increasing degree by the “evil empire,” it is also a sign that consumers have much more power in their hands than they realize. In fact, within the market framework, the consumers have a great deal of power, although this power only stretches so far as the paradigm which supports it. The criticism that this approach doesn’t engender “real change” is a legitimate one, as we have seen and will continue to explore.

This leads me to something of a tangent, but I hope you’ll bear me out, as it is relevant to this counter/mainstream dialectic. The lottery, television award shows such as “American Idol,” and mainstream movie icons are all carrots which keep the middle and lower classes on the corporate treadmill, accumulating debt for the sake of another’s profit. Sex, also, and the repression and structuring of the sexual impulse, are similar mechanisms of motivation and manipulation.

In management, other myths prevail, still rooted in the idea of teleological progress: the representations of success matter more than the things they represent. As a matter of fact, they replace them. The sports car, the expensive watch, the designer suit are all, from a utilitarian perspective, often less valuable than items half their cost. Though luxury items such as these are said to cost more because of increased craftsmanship – which may well be true – the customer is still buying them because they are symbols of wealth and success. To have either of these on their own is not enough; the symbols are of greater value.

Though this seems harmless enough in itself, a common indulgence of the upper class, it is the same mis-valuation (weighing the symbol over what is represented) which leads to vastly damaging business practices. The social dynamics of “have” and “have not” polarize – and thereby power – the ecology of the economy. This dialectic is not an unfortunate by-product, it is an essential constituent. What American doesn’t think they too might one day be rich, or famous? How many in the American working class would be able to go to their tedious job every day without that dream of success to keep them going?

A friend of mine, who has had decades of entrepreneurial experience dealing with many national and international brands, summarized the mentality of American ‘business-think’ rather well: “if you’re smiling when you close a deal, you’re not fucking the person over… even if you are.” The almost cultish corporate mentality which puts all weight on what a thing seems rather than what it is culminates in a complete lack of responsibility for the repercussions of corporate actions. The movie Czech Dream by Vít Klusák and Filip Remunda implicitly explores one side of this; however you can easily see it in most business-oriented NLP seminars. Myth itself is based on the principle of the “seeming” (naming) of things, and so this could very well be called an underlying “myth of business.” The surface is the thing, and the value is in the illusion that serves the interests of profit and unmitigated “progress” at any cost, so long as that cost is not felt in the boardroom. The ethical value is not to be seen in the content or method of action of a myth, but rather in its social effects. At face value all myths are morally ambiguous.

Thus, the utopian dreams of most countercultures are rendered somewhat toothless by the brilliantly co-optive myths of capitalist culture. One might hope this is a temporary state of affairs, as the hippy movement hoped that primal territorial and ideological conflicts are some sort of prolonged hold-back rather than the underlying reality of the human condition. Regardless, hope alone does not bring change. The paradigms that root a culture in ideological stasis are too strong for any single “revolutionary” or grass-roots movement to effectively shift them all at once – all that results from demonstrative radicalization is further polarization, disenfranchisement and estrangement. If, on the other hand, people find alternatives that truly work for them, which allow for new cultural possibilities (and blind-spots), they will likely spread by virtue of their efficacy. If social groups can establish greater sufficiency, they become less dependent on the structures of government and business, though it’s unlikely they’ll be able to escape the establishment of their own versions of the same. It almost seems that such things can only happen blindly, naturally, as bees pollinate flowers.

So we come to it.

As counterculture scenes grow and enter the market place – all the elements of it have been defined, commodified, and made replicable. This is precisely the same process that occurs from one generation to the next. It isn’t that any subculture – or any “scene” for that matter – needs to be revitalized once it has reached this stage. They are all dead shells, ideas which at one point in time served a purpose, and are now just fetishes.

We can continue to build places, both virtual and material, that can be utilized by people who share common goals. We can continue to evolve and avoid being stuck into our cast off stereotypes. The capacity for creation is never outweighed by the capacity for destruction; the two are mutually dependent. Over-identification with ideas creates stereotypes.