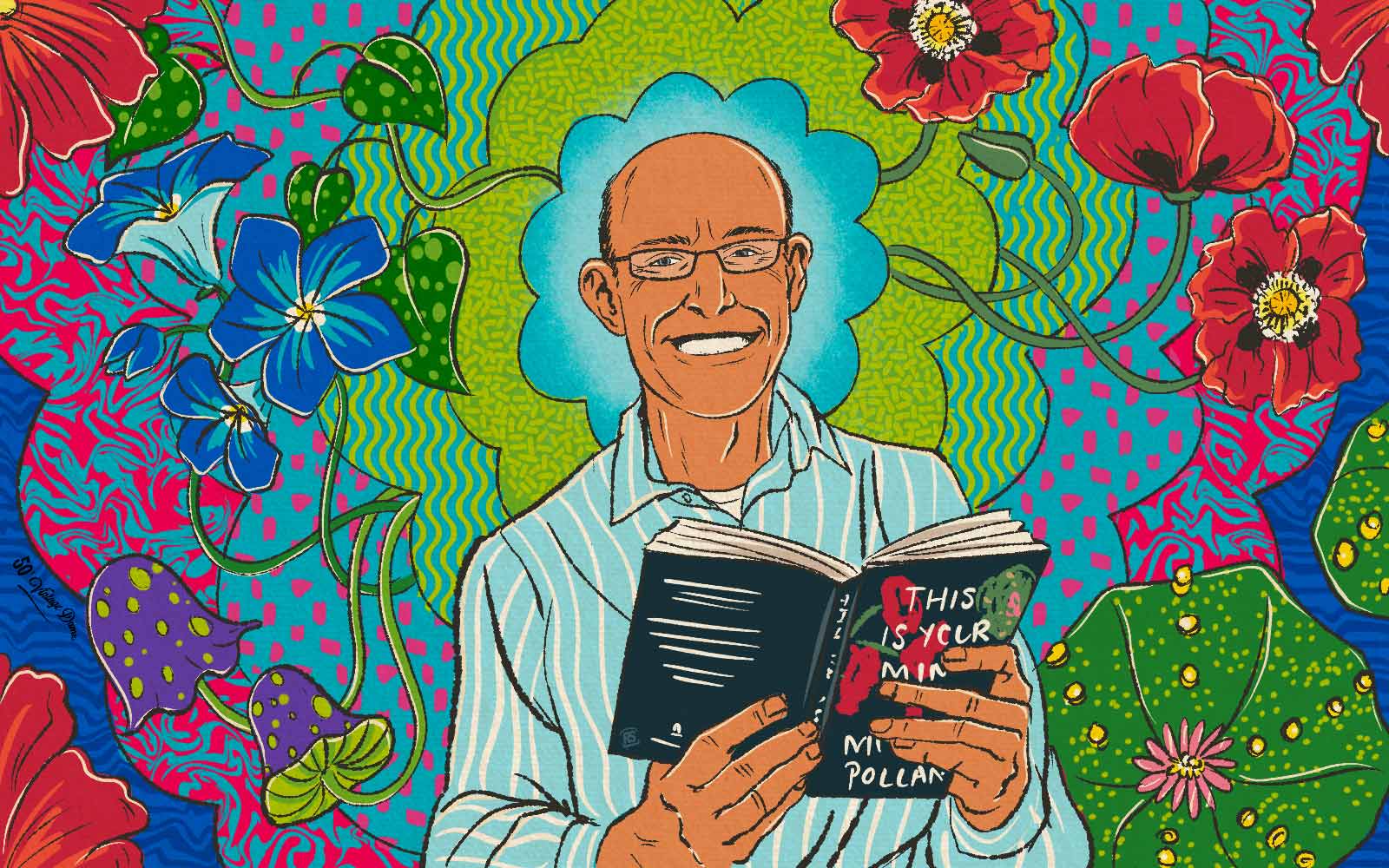

Just as Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax speaks for the trees, writer, gardener and nature enthusiast Michael Pollan sheds light on the intersection of plants and the individuals and societies around them. His writing educates the reader on how the silent photosynthesizing majority influences and inspires their human counterparts. As 50 years of federally mandated drug attacks begin to slow, leading experts and the voting public voice their interest in formally stigmatized illicit substances. In his latest exploration, This Is Your Mind on Plants, Pollan dives into the intricacies of the legal and social structures surrounding three notorious psychoactive substances: opium, caffeine and mescaline. Through his personal experiences with growing, using and learning the histories of these powerful plant medicines, Pollan reshapes traditional substance hierarchies and brings his reader back to the real root of the matter: the plants.

Pollan splits the book into three sections, each highlighting each plant’s scientific, historical, and personal significance. Though Pollan is a prominent voice in the psychedelic community, he weaves his personal experiences with Indigenous wisdom, political perspective and scientific specificities. Let’s start with perhaps the most controversial plant: opium.

Opium

Pollan starts by rehashing the past, specifically, a 1996 article for Harper’s Bazaar magazine inspired by the underground press book, Opium for the Masses. At the time, the War on Drugs was at its peak: The 1990s brought along new and stricter drug laws, giving the government power to confiscate more property and incarcerate more people. As the Clinton administration prosecuted drug-related offenses with concentrated fervor, Pollan—a curious gardener, history lover and psychonaut—was intrigued by the thought of growing long-stemmed, scarlet and black poppies that—with somewhat careful extraction— produce an ancient and influential homegrown narcotic. After researching, Pollan found an underground community of radical gardeners producing opium extracts and plenty of a legal grey area surrounding the cultivation, sale and processing of these easily attainable plants. Here he warns the reader, as the grey area becomes more black and white once the prospective poppy gardener knows of the narcotic possibilities within this beautiful flower.

With some trepidation, Pollan continued his opium investigation: Nurturing his verdant poppy sprouts, harvesting the seeds, and trying his hand at brewing opium tea. As he delved deeper, the looming possibility of governmental suspicion became threatening enough for him to remove four pages detailing his opium tea recipe and psychedelic experiences from his final article. In This is Your Mind on Plants, he finally shares the extent of his decades-old opium exploration and integrates his refreshed perspective.

The year 1996 didn’t just mark the beginning of Pollan’s foray with opium poppies but also signaled the launch of Purdue Pharma’s aggressive marketing campaign for their new, “non-addictive” synthetic opiate: Oxycontin. Pollan outlines the cruel irony of the government cracking down on small-scale poppy growers — in an attempt to curtail the creation of a new-fangled trippy fad — while allowing the owners of Purdue, the Sackler family, to profit 35 billion dollars from legal opiate sales. Powerful interests guide the government’s hand in deciding which substances are sanctionable and how to best govern citizen’s consumption.

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most studied psychoactive compounds, perhaps because it exists in many forms — plentifully and legally — in homes, workplaces and grocery stores worldwide. Pollan begins his investigation of this prolific chemical with yet another warning. Deep exploration can often uncover harsh truths, and for the millions of people reliably starting their day with a cup of caffeinated fuel, Pollan’s findings could leave them regretfully enlightened.

Coffee and tea — two plants that naturally produce caffeine—have outsourced their reproductive needs to humans, thanks to their evolution-granted ability to create pleasurable and addictive chemicals. This adaptation allows these plants — namely Coffea and Camellia sinensis — to expand their habitat and populations beyond their native homes for the perceived benefit of human civilization.

Pollan himself is an avid caffeine user, starting his day with a coffee and substituting with green tea throughout the day, sometimes partaking in a sneaky after lunch or evening cup of joe.

The Western world was introduced to coffee and tea in the 1600s — relatively recently compared to native groups in Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and China. Pollan theorizes a connection between Europe’s shift from mystical medieval thinking toward the more rational Enlightenment Era and the introduction of caffeine to the intellectuals and masses.

Since clean water was hard to come by, working people often drank alcohol as a safer alternative throughout their workday. Hot caffeinated beverages require people to boil water, therefore killing bacteria and boosting public health. As the industrial revolution moved labor forces indoors, coffee and tea helped keep the workforce focused and work with less sleep for longer hours. Even today, most employers provide coffee or tea to their workforce and allow time off from work to partake in the socially acceptable “coffee break.”

To get a better sense of caffeine’s hold on himself and society, Pollan decided to abstain from coffee and green tea for three months — much to his building displeasure. After powering through the caffeine withdrawals, Pollan was able to finally see the vicious cycle of dependence hidden behind socially acceptable substance use. After his pained hiatus, Pollan experiences the full psychoactive effects of caffeine for what felt like the first time. Focused, antsy and driven, Pollan accomplished all of his household tasks and vowed to keep his coffee habit limited to Saturday mornings. This seemed the best way to experience the benefits intentionally and mitigate the caffeine maintenance behaviors that come along with daily, continual use. This proved a new challenge, though best left to Pollan’s eloquent epilogue for the whole conclusion.

Mescaline

The final of Pollan’s exploration turns towards the mescaline containing peyote and San Pedro cacti. Indigenous American communities discovered these cacti’s psychedelic properties and are the only group of people allowed to cultivate and process mescaline in the United States legally. Rounding out his trio of substances for this book, Pollan was set to experience a Native American ceremony at the Laredo Peyote gardens. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, his investigative and psychedelic aspirations got shut down. Now dealing with the panic and anxiety of the world around him, mescaline proposed an intriguing solution to the seeming stagnation and confinement of his “new normal.” Mescaline has a long tradition of treating the wounds of circumstance.

The roots of peyote use lie in the 6000-year-old traditions of Indigenous North American Peoples, making mescaline the oldest known psychedelic. German and Austrian chemists first synthesized the mescaline molecule in the 1900s, but the wealth of Indigenous knowledge still outweighs the western public’s understanding of this powerful plant. While colonizers and settlers committed genocide and pushed Indigenous communities off their land, the Native American Church expanded its sacramental use of mescaline. Mescaline allowed communities to come together and feel the collective spirit while viciously under attack. Today there is a shortage of peyote cacti, making outsiders’ participation an unnecessary variable for the already high demand.

The ethical dilemma weighed on Pollan, as he learned the importance of specifically wild peyote for Indigenous spiritual practices, limiting the desire for cultivated cacti. Not only did his participation pose moral questions, but by publishing his experience as a well-known author, he could encourage others to seek out their own experience.

Lucky for Pollan, he happened to have San Pedro cacti growing in his front yard. Though peyote has higher concentrations of mescaline, San Pedro is a more abundantly available source. To establish the proper setting, Pollan wanted to abide by certain ceremonial practices. He then found a woman to lead him and his wife through a San Pedro ceremony recounting the experience with tenderness and respect while acknowledging the culturally appropriative dilemmas.

Pollan gives his readers a well-rounded and intimate exploration of plants shrouded in preconceived ideas, blind ignorance and powerful significance. He describes the narrative that he hopes This Is Your Mind on Plants can correct:

“The drug war’s simplistic account of what drugs do and are, as well as its insistence on lumping all of them together under a single meaningless rubric, has for too long prevented us from thinking clearly about the meaning and potential of these very different substances.”

Pollan succeeds at shifting this narrative by examining Indigenous wisdom’s historical significance and integrating the two with his personal stories.

Have you read This Is Your Mind on Plants or any of Pollan’s other bestsellers? We would love to have a conversation in the comments below.