Experience is the ground.

Awareness is the path.

Expression is the fruition.

–Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

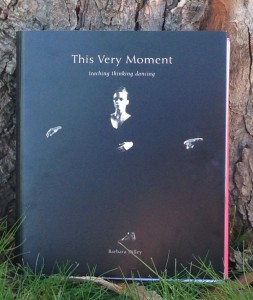

This Very Moment: Teaching, Thinking, Dancing is a new book by Barbara Dilley. It’s a hybrid text whose through-line is a memoir of her extraordinary career from the cutting edge of dance in America in the 1960s to her four decades of teaching dance as a contemplative practice; it’s part aesthetic meditation, part historical reflection, part manual for dance as mindfulness practice.

The layout is large-format with lots of photographs and it’s bound so as to lie flat on the studio floor, so you can refer to it while doing the exercises and executing the scores in the five “Practices” sections.

The book opens with an epigraph from the novelist E. L. Doctorow:

Writing is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.

That’s a powerful metaphor, though it addresses only the myopia of night driving, while the watchful artist in the light of day has to deal with multiple dimensions in addition to the way forward. And the novelist’s metaphor neglects the option of stopping. The artist can stop: unlike the driver, the artist can do nothing and still make progress.

This idea has been key to the work of poets, painters, musicians, and dancers of the American avant-garde since artists such as Ad Reinhardt, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Sari Dienes, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, the Beats, and the Fluxus group (among many others) came under the influence of Buddhism through travels, reading, osmosis, lectures by visiting Buddhist teachers, and/or D. T. Suzuki’s classes at Columbia University beginning in 1952.

But the influence was not merely a matter of artists adopting novel ideas from Buddhist teachers. As Alan Watts pointed out in 1954 …

It is not quite correct to say that a ‘Zen influence’ is simply being imported and imitated. It is rather a case of deep answering to deep, of tendencies already implicit in Western life which leap into actuality through an outside stimulus. [1]

Art in the west has travelled a path from mimesis, or representation of perceived reality (Classicism); to art as “self-expression” (Romanticism); to a greater emphasis on medium — painting is about paint, music is about music (Modernism)[2]; and finally to art as a phenomenon of consciousness not necessarily expressive of a “self” (Postmodernism).

The latter phases of this shift came about as a result of a whole constellation of material and ideological realities, and not solely as the result of influences from the East. Buddhism didn’t cause the shift, but it entered the picture in time to offer emerging artists of the post-world-war avant-garde a perspective and set of principles rooted in two millennia of meditative awareness.

During his travels in Asia in the 1950s and ’60s, the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt made a list of principles for art making that is emblematic of the impact of Buddhist teachings on art. Some of those principles are asymmetry, simplicity, naturalness, unconventionality, inner quietness, humor, and freedom.[3] John Cage added silence and emptiness.

Buddhist aesthetics has remained current in the arts of the west down to the present along multiple vectors, including a constellation of artists and scholars who, in the 1970s, embraced Buddhist teachings under the guidance of the Tibetan lama Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and gathered to convene a series of summer institutes in Boulder, Colorado that eventually became Naropa University, the first Buddhist college in America.

Barbara Dilley began studying ballet in 1950 and danced at the Princeton Ballet Society. In 1955 she attended Jacob’s Pillow, the summer dance academy and performance festival founded by modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn. At Mount Holyoke College she was mentored by Helen Priest Rogers, who had danced with Martha Graham. In 1960, Dilley moved to New York City and began studying with Merce Cunningham. In 1962 she joined the Cunningham company.

Dance is the most immediate and ephemeral of arts. Unlike that other time-based art, music, there isn’t even a way to notate it with any degree of accuracy. As a musician, I can learn to play a Bach suite from a printed score. Dance is different; the training and the preparation of performance requires the presence of teacher and student, choreographer and dancer, in a shared space in real time.

You have to love dancing to stick to it.

It gives you nothing back, no manuscripts to store away,

no paintings to show on walls and maybe hang in museums,

no poems to be printed and sold,

nothing but that single fleeting moment when you feel alive.

–Merce Cunningham

Of course there is video technology now, and dancers use it to teach, to record the creative process, and as an aid to memory, but the presence of the choreographer or teacher and fellow dancers is, to an extent greater than is true in other art media, irreplaceable.

Dance training involves personal transmission from one dancer to another, and it links generations, person to person, like Indian classical music, like the living ancient arts of all cultures, like Buddhist teachings going back 2500 years.

Unlike the lineages of Buddhism, the lineage of American modern dance goes back little more than a century. Its first two generations of major movers can be counted on one’s fingers.

Among the third generation of modern dancers, Merce Cunningham was one of the most innovative and influential. Cunningham and his partner, composer John Cage, were key figures in the post-world-war American avant-garde, and they instantiated the transition from modernism to postmodernism in the performing arts.

John Cage had a big influence on the generation of artists among whom Barbara Dilley made work in the thriving, interwoven experimental art scenes of New York City in the 1960s. Cage’s aesthetic was essentially Buddhist.

Our intention is to affirm this life, not to bring order out of chaos, nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord. [4]

This is why he embraced chance operations, allowing the I Ching to make musical choices for him.

People frequently ask me if I’m faithful to the answers, or if I change them because I want to. I don’t change them because I want to. When I find myself at that point, in the position of someone who would change something — at that point I don’t change it, I change myself. It’s for that reason that I have said that instead of self-expression, I’m involved in self-alteration. [5]

Self alteration is a function of art in Buddhist philosophy, psychology, and practice.

This is why B. Dilley’s book is so valuable. It is an intimate, first-person account of the influence of Buddhism on art in America authored by a unique artist-practitioner who received direct transmission from the major mover of modern dance in the late twentieth century and from a living embodiment of the dharma, and it is a manual for dance as meditation practice.

This Very Moment: Teaching, Thinking, Dancing should be of interest to all artists interested in transformational awareness and to historians of the avant garde in America. For dancers, it’s a movers’ manual for a lifetime.

It’s time to introduce Parallel Corridor Maps of Space. In the mind’s eye, see parallel corridors going from one wall to the other. Three people stand against one wall. Each one in is a Corridor. Take an exploratory walk to the end of the Corridor, turn, and come back. Use the Five Moves ~ Standing, Walking, Turning, Arm Gestures, and Crawling. Call Begin. Use Peripheral Seeing, seeing from the corners of the eyes, one of the Five Eye Practices. Locate gestures from the other two and join them into your movement stream.

The unknown becomes a friend,

absurdity is worn well, fear is gently smiled at.

The making-a-fool quality is always present

when you stand at the edge of empty space

and . . . willingly take the first step.

–Barbara Dilley

Notes

[1] Alan Watts quoted in Charles L. Cohen and Ronald L. Numbers. Gods in America: Religious Pluralism in the U.S. Oxford UP. 2013.

[2] In his Harvard lectures of 1939-40, Igor Stravinsky said “From the moment a song assumes as its calling the expression of the meaning of discourse, it leaves the realm of music and has nothing more in common with it. . . . and “Do we not, in truth, ask the impossible of music when we ask it to express feelings, to translate dramatic situations, even to imitate nature? (Poetics of Music, Cambridge MA: Harvard UP. 1959).

[3] Charles L. Cohen and Ronald L. Numbers. Gods in America: Religious Pluralism in the United States. N.Y.: Oxford UP. 2013.

[4] Kay Larson. Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. Pengiun. 2012.

[5] Ibid.