The following is excerpted from A Way to God: Thomas Merton’s Creative Spirituality Journey by Matthew Fox, printed with permission of New World Library.

Was Thomas Merton himself familiar with art as meditation? Of course he was. First, as a writer, he no doubt experienced moments of ecstasy and union/communion in his research and finding of truth and in sharing it. This is the joyful vocation of a writer. This is surely why he was so fecund a writer, leaving behind dozens of books and hundreds of articles and essays.

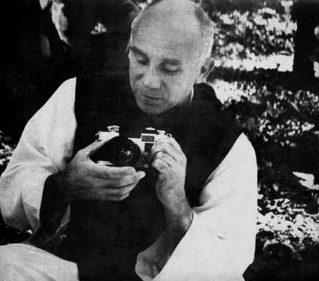

We also know that Merton was a very serious photographer, and we can see in his photography much spiritual depth and insight along with skill and discipline. His friend and official biographer, John Howard Griffin, introduced Merton to his first camera. Griffin subsequently wrote an entire book on Merton’s photography, A Hidden Wholeness: The Visual World of Thomas Merton. He observed that for Merton, “the camera became in his hands, almost immediately, an instrument of contemplation.” He points out how Merton included the Via Negativa in his picture-taking for “his concept of aesthetic beauty differed from that of most men. Most would pass by dead roots in search of a rose. Merton photographed the dead tree root or the texture of wood or whatever crossed his path…seeking not to alter their life but to preserve it in his emulsions.” For Merton, said a friend, “photography is a way of framing wholes so that suchness reveals itself.” But suchness, as Dr. Suzuki put it, is the Cosmic Christ in Christian parlance. For it is about how every being is an image of God. Said Suzuki: “In Christian terms [suchness] is to see God in an angel as angel, to see God in a flea as flea.”

Indeed, on his final journey, Merton was often taking pictures, and he shared with us his philosophy of photography: “The best photography is aware, mindful of illusion and uses illusion, permitting and encouraging it — especially unconscious and powerful illusions that are not normally admitted on the scene.” For Merton it is not the camera that does the taking for “the camera does not know what it takes: it captures materials with which you reconstruct, not so much what you saw as what you thought you saw.” A friend comments that Merton “was not a ‘photographer.’ For him, the camera was merely another tool ‘for dealing with things everybody knows about but isn’t attending to,’ ” as Susan Sontag put it.

Three days before he died, on December 7, Merton recorded in his journal, “I sent contact prints to John Griffin with a few marked for enlargement. Took nine rolls of Pan X to the Borneo Studio on Silom Road, hoping they will not be ruined.” John Griffin wrote the Borneo Studio after Merton’s death and acquired these last photos from Merton, including them in his book A Hidden Wholeness. Thus, they were not ruined. So right up to the end, Merton was engaged with his photographic vocation — art as meditation, indeed! Griffin described his last meeting with Merton before he left for his Asian trip, which included a telling description of the joy that Merton found in art as meditation:

On my last visit with him before his trip to Asia, we went out together to photograph. He had now developed a photographer’s eye. He became excited by almost everything he saw — the peeling paint on window facings, plants, weeds, the arrangement of a stack of wood chips….I photographed him in the act of photographing, an activity in which his joy was unblemished and which added a special aura of happiness to his features.

Yes, art as meditation does bring joy, and it brought joy to Merton right up to the end.

Psychologist and ex-Benedictine Thomas Moore had this to say about Merton’s love of photography:

I am also inspired by Merton’s practice of photography. Notice that I connect his art with his spiritual life as he did in his writing. It makes complete sense that he would have discovered an art that smoothly connected his contemplative life with the world around him in a form analogous to his writing….he wrote his books and his casual writing, if you can call it that, as an artist careful with his style, even though he was such a master at it that it seems easy and natural. Most artists move from a primary art to a secondary or complementary one, and Merton’s turn to photography was a major movement in his life.

Moore names Merton’s discovery of photography as an art and prayer form “a major movement” in his life. Moore elaborates on the role of art as meditation in Merton’s vocation:

Merton’s photographs inspire me to connect the arts to the spiritual life as integrally and as tightly as possible. When I encourage people to engage an art as spiritual practice I often remind them how in history and around the world religions and the arts have been linked so closely that it’s difficult to imagine one without the other. But Merton refines that idea. He invites us to zoom in on it and notice that our meditations are complete when we can use the lens of a camera to see the interiority or the art forms of the world around us. The camera frames our world so that we can transform it into an image that speaks to the soul and spirit and is an object of contemplation.

Merton admired the Hindu tradition in which all artistic work is recognized as a form of yoga. In this way, he commented, “there ceases to be any distinction between sacred and secular art. All art is Yoga, and even the art of making a table or a bed, or building a house, proceeds from the craftsman’s Yoga and from his spiritual discipline of meditation.” This is a fine way to name the process of art as meditation, and Merton does so word for word. Indeed, by embracing a “craftsman’s Yoga,” Merton endorses a broader spirituality of work. He wrote: “Your work is your yoga and it can lead to a sense of being one with God….Basically, Hinduism says that your everyday work can lead you to union with God. No matter who you are, no matter how material the work is, it can unite you with God.” This parallels my theology, and my teaching of the “priesthood of all workers,” as laid out in my book The Reinvention of Work, which was the basis of the unique doctorate of ministry I created at the University of Creation Spirituality.

Merton also turned to calligraphy as an art and meditation experience. Griffin wrote, “Thomas Merton referred to his calligraphic drawings in a variety of terms…he called them abstractions, abstract writings, marks, signatures, signs, and sometimes calligraphies.” Griffin cautioned: “No need to categorize these marks. It is better if they remain unidentified vestiges, signatures of someone who is not around.” Merton held some public exhibitions of these drawings as well. Griffin wrote that Merton

trusted in the “connections” that would somehow be made between the observer and the images, particularly if the observer could see them simply as what they are: Free expressions, signs executed without preplanning, having their own reality. Merton hoped that this reality would not be obscured by undue explanations or analyses…abandon all attempts to decipher “what they mean” or “how to interpret them.”…They ask nothing at all. They demand nothing at all. They just are and that is all. “Does there always have to be a reason for everything?” Merton asked again and again in his writings.

Griffin concluded, “The drawings are free and they leave the viewer free.”

Merton also liked music. He was so in love with jazz that almost every time he could leave the monastery and go into the nearby city of Louisville, he would gravitate to what was then the segregated, black area of town and hang out in the jazz clubs. To this day, many local African Americans, now old, tell stories of hanging out and talking jazz with Merton when they were young. He could play the piano, and he admired the music of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Once, with a third party present, Merton and Baez had a picnic on the monastery grounds, in which Baez reported that Merton got a bit tipsy from too much champagne. When French philosopher Jacques Maritain visited Merton in 1966, Merton described Bob Dylan to him as “the American Villon” and said he was preparing a study of Dylan’s poetry and songs. Merton put on a recording of some of Dylan’s songs and played them at full volume. “The Dylan songs blasted the still atmosphere of Trappist lands with the wang-wang of guitars and voice at high amplification.”

Merton was not the only one who was impacted by Baez and Dylan; I was, too, and during the same time period. In the mid-1960s, while the Second Vatican Council was in session, the strict rules were relaxed in our Dominican training, and we were allowed to listen to recordings of folk singers, of which Joan Baez made a special impression on me. My first encounter with Dylan occurred when a sort of traveling minstrel, a young hippie troubadour walking the country, showed up at our studium in Dubuque, Iowa, and played Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” at the picnic table behind our priory. I was deeply moved. In the 1970s, after I returned to Dubuque after my Parisian sojourn, Peter, Paul, and Mary became the most influential mystic-prophet troubadours among my young Dominican brothers studying for the priesthood.

Merton was also a serious poet. We can feel his soul in his poems, such as in this tribute to the grace one feels while chanting the psalms, a practice that his monastic community undertook several times a day and in the middle of the night:

When psalms surprise me with their music

And antiphons turn to rum

The Spirit sings: the bottom drops out of my soul

And from the center of my cellar Love, louder than thunder

Opens a heave of naked air.

Merton said, “Poetry is not ordinary speech, nor is poetic experience ordinary experience. It is closer to religious experience. Rasa is above all santa: contemplative peace.” In a discussion with Dr. V. Raghavan on rasa and Indian aesthetics, Merton reported that together they “discussed the difference between aesthetic experience and religious experience: the aesthetic lasts only as long as the object is present. Religious knowledge does not require the presence of ‘an object.’ Once one has known Brahman one’s life is permanently transformed from within. I spoke of William Blake and his fourfold vision.” Among Merton’s jottings in his Asian Journal are passages from many writers, which he wrote down possibly for meditation or for future commentary. One such passage from G. B. Mohan’s book The Response to Poetry reads as follows:

Aestheticism which fails to integrate art with life and crude moralism which reduces poetry to sermons perpetuate the end-means conflict. Aesthetic experience is both an end in itself and a means for a fuller realization of human values….By pointing out unsuspected affinities between apparently dissimilar things, by establishing meaningful relations between apparently unrelated phenomena, poetry extends the range of our awareness.

One can presume that Mohan is in some way speaking for Merton’s appreciation of poetry and its capacity to “extend the range of our awareness.”

Merton was also keen about visual art, and he wrote movingly about cave art and iconography, such as in the following story:

No art form stirs or moves me more deeply, perhaps, than Paleolithic cave painting — that and Byzantine or Russian icons. (I admit this may be really inconsistent!). The cave painters were concerned not with composition, not with “beauty,” but with the peculiar immediacy of the most direct vision. The bison they paint is not a mere representation of an animal, it is a sign, a gestalt, a presence of the unique and peculiar life force incarnated in this animal — in terms of Banta philosophy, its muntu. This is anything but an “abstract essence.” It is dynamic power, vitality, the self-realization of life in act, something that flashes out in a split second, is seen, yet is not accessible to mere reflection, still less to analysis. Cave art is a sign of pure seeing, nothing else.

While traveling in India with friend Amiya Chakravarty, Merton visited the home of painter Jamini Roy, “a warm, saintly old man,” where Merton described encountering “simple, formalized little icons with a marvelous sort of folk and Coptic quality absolutely alive and full of charm, many Christian themes, the most lovely modern treatment of Christian subjects I have ever seen.” Merton concluded, “All the faces glowing with humanity and peace. Great religious artists. It was a great experience.”

Merton had a powerful experience in meditation at the large sacred statues of the Buddha at Polonnaruwa, Ceylon.

I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of Madhyamika, of sunyata, that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything — without refutation — without establishing some other argument.

He explains how it hit him so hard, becoming a breakthrough event:

I was knocked over with a rush of relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures, the metal bodies composed into the rock shape and landscape, figure, rock and tree. And the sweep of bare rock sloping away on the other side of the hills, where you can go back and see different aspects of the figures. Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious….The rock, all matter, all life, is charged with dharmakaya…everything is emptiness and everything is compassion. I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together on one aesthetic illumination.

He tells us that this mystical/aesthetic experience with the Buddha statues was the culmination of his pilgrimage to the East. “My Asian pilgrimage has come clear and purified itself. I mean, I know and have seen what I was obscurely looking for. I don’t know what else remains but I have now seen and have pierced through the surface and have got beyond the shadow and the disguise. This is Asia in its purity.”

Sister Lentfoehr said that, in a Chilean magazine interview in 1967, Merton “named himself not only the author of ‘many books of prose and poetry’ but also an artist, and though living ‘as a hermit, solitary in the forest in contact with groups of poets radicals, pacifists, hippies, artists, etc. in all parts of the world.’ ” It is true, Lentfoehr observed, that “Merton considered himself a poet, and he was that, and it is highly interesting to trace his poetic development over the years — from the early poems which he chose to keep, to his latest, so-called antipoetry, strongly marked by sociological concern and a richly orchestrated neo-surrealist technique.” Ross Labrie, in The Art of Thomas Merton, concluded that Merton is

recognized as an important figure in recent American poetry. The range of his work strikes one in retrospect as impressive — from the austerely beautiful religious lyrics of the early period to the inventiveness and structural complexity of the later style. In the late 1960s he had finally come to feel that the poet and the contemplative in him were one, and this confidence gives the later poems an attractive energy and buoyancy that seem in hindsight to have been full of promise.

Merton was a poet, an essayist, a diarist, a narrative writer, and a spiritual author. He told his friend Robert Lax that his poems helped his calligraphies, his calligraphies helped his poems, and his calligraphies helped his manifestos. He identified himself as a writer, confiding to a friend, “There is something in my nature that gets the keenest and sharpest pleasure out of achievement, out of work finished and printed and distributed and read.” The Via Creativa, indeed!

As we have seen, Merton was also a photographer, a lover of visual art and music, and he drew as well. He was also very outspoken and very much practiced in the art of friendship — an art form that is often quite rare in American society, especially among men. Indeed, this was driven home to me when I was living on a Basque farm in the foothills of the Pyrenees in southwestern France (Merton was born in Prades, France, in the southeastern Pyrenees). One night in the local family-run inn where I ate my dinners, we watched the first moon landing on a black-and-white television. Afterward, an unknown visitor came to see me, a ninety-year-old Basque priest who came limping through the door on a cane. He approached me, shook my hand excitedly, and extended his congratulations: “Bravo!” he said. “Who but the Americans could land someone on the moon? Congratulations!” Then he added, “But when it comes to friendship, you Americans are morons.” And with that he turned around and left the room.

Merton was not a moron. His friends and friendship were important to him. Sister Lentfoehr reminds us that in September 1968, just three months before his death, Merton wrote an article entitled “The Monastic Theology of St. Aelred,” a saint and English Cistercian. Merton had studied St. Aelred in depth as a young monk, especially Aelred’s well-known treatise on friendship. Merton wrote, “The natural basis for this theology of friendship is of course the indestructible inclination to love which is the divine image in us.” He employed the phrase “an apostolate of friendship” — and he practiced it. In just one collection of Merton’s letters, the great range of individuals he wrote to included people in Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, England, Japan, and Pakistan. As one person put it, this testifies “to the ever-widening circle of friendships he built through his correspondence.” Of course, this was decades before email! Among his friends by correspondence were peace activists such as Dorothy Day, James Forest, Jean and Hildegard Goss-Mayr, Dan and Philip Berrigan, and Gordon Zahn; writers such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Wendell Berry (who visited him in his hermitage), Boris Pasternak, Czeslaw Milosz, Bill Everson (Brother Antoninus, who visited him in his hermitage), and Henry Miller; psychologists and psychoanalysts such as Erich Fromm, Karl Stern, and Joost Meerloo; scientists like Leo Szilard, and more.

John Howard Griffin, one of his closest friends, said that Merton had a “genius for friendship.” Griffin wrote:

Thomas Merton found no inconsistency in seeming opposites. He was a hermit, with a true vocation for solitude and at the same time he had such a boundless affective nature that he made and cherished deep friendships. He counted as friends the famous and the unknown of the world. Many who never met him except through correspondence were authentic friends. He had a genius for friendship in that he gave of himself without demanding anything. His closest friends reflected that genius, never intruding unduly, leaving him free as he left others free.

One friend Merton made on his final trip to Asia was Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who was only thirty-one years old at the time and made a deep impression on him. Merton considered him “a good friend of mine — a very interesting person indeed…who got the complete reincarnation treatment: a thorough formation in Tibetan science monasticism, and everything,” and who had to escape from Tibet “to save his life, like most other abbots.” Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche later started the Naropa Institute (which became Naropa University). After his death, Naropa University linked up with my University of Creation Spirituality and accredited our master’s program in Creation Spirituality in Oakland for seven fruitful years.

***