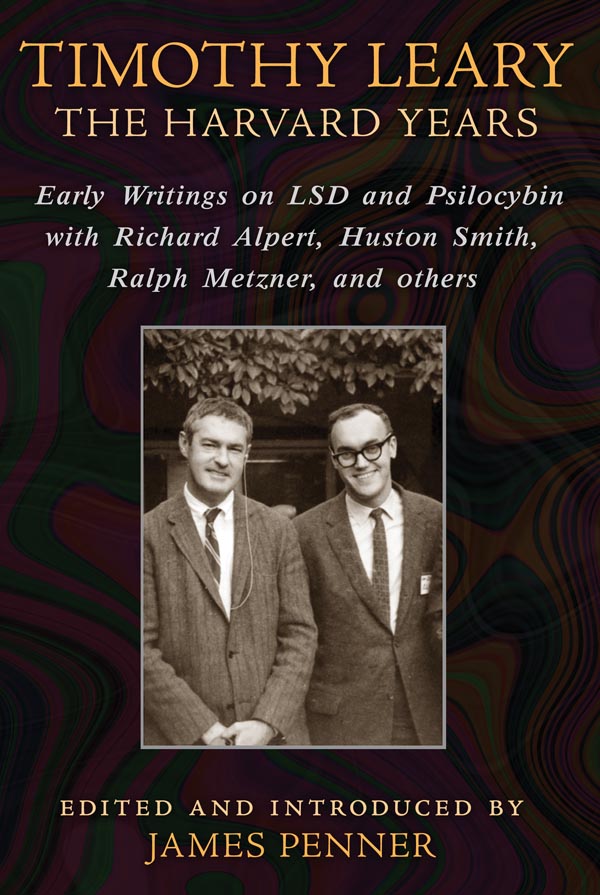

The following is excerpted from Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years, published by Inner Traditions.

When I first began researching Timothy Leary’s writings from the 1960s, I gradually realized that Leary was quite difficult to pin down. Throughout his life, Leary was keenly interested in exploring radical forms of self-transformation. It is clear that psychedelic drugs were an important part of his ongoing attempt to shape and remake his identity. I noted how multiple conflicting versions of Leary seemed to coexist within the media, the popular culture, and his biography. There was Leary the scientist, Leary the radical Harvard psychologist, Leary the mystic and self-proclaimed high priest, Leary the iconic rebel and trickster, Leary the hippie and irresponsible advocate of LSD, and, of course, Leary the celebrity. Leary himself was aware of all of the identities that he had cultivated and constructed throughout his life. He even referenced his own weakness for what he called “the individuality game” in an important speech he delivered in for the International Congress of Applied Psychology in 1961: “[a]nd that most treacherous and tragic game of all, the individuality game. The Timothy Leary game. Ridiculous how we confuse this game, overplay it.” Leary’s self-critique was intended as a way of illustrating the ways in which our identity is an egotistical game that we relentlessly play throughout our lives. For Leary, the psychedelic drugs were extraordinary because they offered ephemeral release from the “treacherous” identity game: a way of disentangling ourselves from the social roles that seemed to envelope our entire being.

As I began to read and sift through all of Leary’s essays and articles in preparation for Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years, I eventually became obsessed with the Harvard Drug Scandal of 1962 and 1963. To me, it seemed to be the quintessential prophetic event for the tumultuous 1960s; Leary’s psilocybin research at Harvard was a cultural incubator for the nascent counterculture and President Pusey’s repressive actions—firing Leary and Richard Alpert without a public hearing—demonstrated how bureaucracies and cultural authorities were wont to suppress social movements that they could not control nor fully understand. As I traced Leary’s trajectory during the scandal, I tried to understand how and why Leary’s promising academic career was so abruptly destroyed. Was it a case of professorial self-destruction? Or was the Harvard administration overzealous in their response to a scholarly conflict over research methods that should have remained within the confines of the psychology department?

When examining the details leading up to the scandal, what surprised me the most was Leary’s nonchalant attitude throughout the conflict. During the worst moments, he seemed unfazed by the prospect of being fired by America’s oldest and most prestigious university. At a certain point, he even seemed to welcome being thrown out of the academy for he somehow knew that the scandal would catapult him to celebrity status and provide him with a much larger podium. Although Leary made some mistakes, his boldness—what others would deem as carelessness—seemed quite admirable to me. It was apparent that Leary’s boldness was a byproduct of his Faustian experimentation with psychedelic drugs. Psychedelic drugs empowered him to transcend professional conflicts that would have destroyed many other people in his situation.

When I researched Leary’s response to the Harvard Drug Scandal, I gathered all the articles that Leary published after he was fired in 1963. The period of 1963 to 1965 interested me the most: what would Leary say and write about when he was no longer beholden to Harvard and the exigencies of his former profession? As I sifted through Leary’s post-Harvard articles, I noticed a distinct trend that emerged in the mid-1960s. At a certain point after 1965, Leary gives up writing for scholarly publications and focuses on attracting a larger audience of psychedelic followers and readers. The change can clearly be seen in the Playboy interview of September of 1966 and in his book, The Politics of Ecstasy that appeared in 1968.[i] In some cases, The Politics of Ecstasy contained watered down versions of his scholarly essays. One of Leary’s best articles from 1963—“The Religious Experience: Its Production and Interpretation”—was rewritten and given a new title (“The Seven Tongues of God”) that was designed to appeal to Hippies and the counter culture.

The new version of Leary—what might be termed the populist Hippie version of Leary—focused on writing for the generation that was under thirty. During the course of reinventing himself in the mid-1960s, Leary’s thinking and writing became, to my mind, somewhat impoverished. His writing often lacked the sophistication and complexity of his scholarly writings on LSD and psilocybin for the early 1960s.[ii] In the context of the ongoing Viet Nam War and the 1968 election, the tone of Leary’s writings on several occasions became shrill and divisive; the over-50 generation predictably became his bête noir: “… white, menopausal, mendacious men now ruling the planet” (The Politics of Ecstasy 363). In his writings and interviews in the late 1960s, Leary often employed crude arguments to mock the older generation that had never experimented with psychedelic drugs: “[m]any fifty-year-olds have lost their curiosity, have lost their ability to make love, have dulled their openness to new sensations, and would use any form of new energy for power, control, and warfare” (The Politics of Ecstasy 123).

As the 1960s progressed, the polemical and hyperbolic version of Leary eventually overshadowed the scholarly and more introspective version of Leary. Today, the general public is most familiar with the hyperbolic version of Leary that emerged in the late 1960s. In the obituaries that were written in 1996, Leary is remembered as the patron saint of the hippies and for his whacky media stunts (running for Governor in California in 1970). With the publication of The Harvard Years, I hope to shed light on the largely forgotten Leary of the early 1960s. The Leary of the Cambridge and the early Millbrook years is a scientist and a radical psychologist who is attempting to reform the treatment of mental illness and the clinical practices of his profession. The Leary of this era does not resort to crude polemics; he writes for skeptics as well as acolytes. He is a public intellectual with one foot in the academy and the “science game,” but he is also part of a much larger social movement—the consciousness expansion movement—that would eventually transform the zeitgeist of the 1960s.

As we enter the twenty-first century, Leary is relevant because psychedelic medicine is currently experiencing a revival. In the last ten years, various American universities and medical colleges (Harvard, Johns Hopkins, UCLA, NYU, and the University of Arizona) have been conducting FDA approved studies on psilocybin and LSD. In the next five years, researchers plan to use psychedelic medicine to treat drug addiction, alcoholism, and end-of-life anxiety that stems from terminal illnesses. When medical authorities and researchers, debate the efficacy of psychedelic substances and patient-centered forms of treatment, Timothy Leary’s name inevitably enters into the discussion. For some, Leary is a hero who fought for the “fifth freedom”: the right to expand one’s consciousness. For others, Leary is an irresponsible opportunist who recklessly promoted the recreational use of LSD. In other cases, people advocate or reject Leary without actually reading his work.

Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years was created to promote a reexamination of Leary’s early scholarly work; it contains essays and articles from the radical psychologist’s most prolific period: 1960 to 1965. His writings demonstrate why he became the iconic leader of the conscious-expansion movement of the 1960s, but, more significantly, they provide a historical context for research in the present day. Leary’s early writings are fascinating because he explores the utopian potential of psychedelic drugs: their unique capacity to transform and enlarge human perception and our understanding of consciousness. From a contemporary perspective, some of Leary’s research projects may appear misguided (read too utopian), but we can learn from his bold experimentation and his speculative thought process. In many cases, he was willing to ask many of the foundational questions that researchers are still grappling with today: can psychedelic drugs be used to alter self-destructive forms of behavior (i.e., alcoholism and drug addiction)? How can psychedelic drugs be used to foster the creative impulse? Can psychedelic drugs aid and facilitate mystical experiences? As research comes full circle some fifty years after the Harvard Drug Scandal, Leary—the probing scientist and radical therapist—also needs to come back into focus.

James Penner will read and discuss Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years at the Harvard Coop on Thursday, March 26th at 7:00 pm. The Harvard Coop Bookstore is located at 1400 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02238. (617) 499-2000.

Works Cited

Leary, Timothy. “She Comes in Colors.” The Politics of Ecstasy. (Berkeley, 1990): 118-159.

Notes

[i] In the Playboy interview of September 1966, Leary abandons “the science game” and makes hyperbolic statements to the media. He egregiously remarks that “[i]n a carefully prepared, loving LSD session, a woman can have several hundred orgasms” (129).

[ii] High Priest (1968) is the exception to the trend. It is Leary’s most impressive attempt to write for a wider audience; it documents the quintessential trips that transformed his life and professional career. In this highly autobiographical text, Leary explores the psychedelic experience from a wide range of vantage points. High Priest is vastly superior to The Politics of Ecstasy (1968).