“Through use of this ‘vine of the soul’ the paye (shaman) believes he can diagnose and treat illnesses…he is thought to regulate birth and death; …hunting and fishing; the weather; travel on the rivers and [bodiless] trips through the forests…”

—Richard Evans Schultes

Despite the recent surge in mainstream popularity of the vine (due primarily to celebrity culture, Elle, Oprah, and National Geographic) the subtle occult, paranormal, and metaphysical aspects of ayahuasca—for those who have dedicated their entire life to understanding and working with it—are still very much in need of further exploration.

Sensationalist coverage such as Lindsey Lohan’s recent “illegal vomit” stint also tends to gloss over the incidents of death and rape that have occurred by dark shamans taking advantage of unprepared Westerners with fat wallets. [1] There has been many eye witness accounts given by experienced anthropologists on the dangers of brujeria, or death by invisible darts conjured by brujos in the Amazon and other global indigenous cultures. [2]

Below are books in order of publication that contribute to a considerably more complex and multifaceted view of the sacred medicine.

Visionary Vine: Hallucinogenic Healing in the Peruvian Amazon (1972)

A Hallucinogenic Tea, Laced with Controversy: Ayahuasca in the Amazon and the United States (2008)

Fate, Fortune, and Mysticism in the Peruvian Amazon: The Septrionic Order and the Naipes Cards (2011) by Marlene Dobkin de Rios

Like Weston La Barre’s groundbreaking work in 1970 on Peyote (The Ghost Dance), de Rios’ was another early anthropological pioneer who dared to extensively document in 1972 how religion and mythology of ancient civilizations were inextricably related to psychoactive plant medicine. While the early texts in her oeuvre are somewhat dry and academically oriented, each of these books form an unofficial trilogy, and are all must reads for how healing and divination is conducted within ayahuasca ceremony.

A Hallucinogenic Tea is an especially interesting look into the political turmoil and increasingly complex politics occurring in the upper Amazon due to tourism, which creates supply and demand issues with the vine in the U.S., and should be a warning sign that sustainable practices should be strictly enforced, as they are by the recently formed The Ethnobotanical Stewardship Council. See also “Ayahuasca and It’s Mechanisms of Healing“, excerpted from Visionary Vine.

Vegetalismo: Shamanism among the Mestizo Population of the Peruvian Amazon by Luis Eduardo Luna (1986)

This early pioneering work also presents a considerably occult interpretation of the vine. Like Steve Beyer, Luna systematically assesses love magic, Soul-loss, illness caused by brujeria, and the hierarchy of the spirit world (containing 8 different sub categories). As he says:

“The belief in spiritual beings living in the jungle, in the water, and to a lesser extent, in the air, and which interfere with the lives of human beings, often in a negative way, is still firmly established…Spirits may adopt the form of various animals—often of extraordinary proportions—Indian or mestizo shamans, black men, foreign entrepeneurs, rubber bosses, princesses from Western fairy tales, angels with swords from Christian iconography, armed officials, famous deceased Western doctors, etc. or even, as can be seen in some of Pablo Amaringo’s paintings, extraterrestial beings from distant planets and solar systems.”

Luna notes that in Peruvian mythology there are some Christian overtones, in that the main evil spirit is known as the Chullachaki, who has hooved feet and is often depicted as a half-animal hybrid responsible for common abduction stories and other various evil-doings.

This God is shamanically combated by invoking the spirit of the equally powerful Sachamama, who is thought to be a rainbow serpant boa, representing the primordial protective (and possessively constrictive) primordial mother, who Amaringo relates can also miraculously cure snakebites. In this way, primordial mythico-religious symbols (best documented by Rene Guenon, Titus Burckhardt, and more recently in Timothy Scott’s “The Traditional Doctrine of Symbol”) become alive as an interactive holographic matrix within the ingestion of the power plants.

Yaje: The New Purgatory by Jimmy Weiskopf (Columbian edition 1990)

The now out of print classic is a towering inquiry into the lesser-known aspects of indigenous tribes outside of Peru who still utilize the ritual sacrament in Columbia and Brazil. Weiskopf is quite critical of Peruvian shamanism, with the contention that it’s traditional lineage has been corrupted by far too many prying anthropologists and the increasingly prevalent ayahuasca tourism, a booming industry.

While some of the book is weighed down by a slightly excessive length, the tome also has the benefit of painting an intimate and moving portrait of how the patriarchal shaman chief (who he calls the Taita) that remains untrusting of Weiskopf’s essential “gringoness” throughout his apprenticeship, never quite allows him the spiritual answers he seeks, despite his own eventual inner discoveries in his apprenticeship with the vine.

Weiskopf is not without a distinct humility and critical self-awareness in the fact that he seeks a culturally exotic pseudo-father from the Taita, but his overall integrity in confiding the weaknesses and emotionally honest heart based transmissions that come from inner visions more than make up for it his gringo ignorance.

The text also contains the critical distinctions between a yajecero (one who habitually drinks the vine) and a curandero (one who heals using the vine)—meaning that not all those who participate in ceremony may be called upon by the spirit council to engage in the energetic healing of others.

One River by Wade Davis (1997)

Richard Evan Schultes’ legendary account of his 12 years of experience in the early 30’s with psychoactive plants (including datura, yaje, peyote) in the Amazon are well chronicled in this timeless, epic tale. Only the pioneering accounts of Antonin Artaud may rival the strange hallucinatory uncharted experiences on display here.

While not exclusively about ayahuasca, it is perhaps the most accessible account of Schultes, Richard Spruce and his student Wade Davis documentation of Amazon magic, as the stiff analytical consciousness of the otherwise scientifically oriented gentleman are here thoroughly dismantled by the formidable “primitive” power of visionary plant wisdom.

The Ayahuasca Experience: A Sourcebook on the Sacred Vine of Spirits edited by Ralph Metzner (1999)

The academically oriented should likely turn to psychedelic pioneer Metzner for an introduction on grappling with philosophical orientation for the ayahuasca scholar.

Like Metzner’s equally fascinating Sacred Mushroom of Visions on psilocybin lore, the book is split into two equally comprehensive halves. The first is dedicated to an excellent historical introduction dealing with ethnopharmacologic history led by Dennis McKenna, psychological dissection by Charles Grob, and neuropharmacological issues by J.C. Callaway.

The second portion of the text is selectively peppered with quality experiences on par or better than anything you can find on experiential accounts on Erowid.

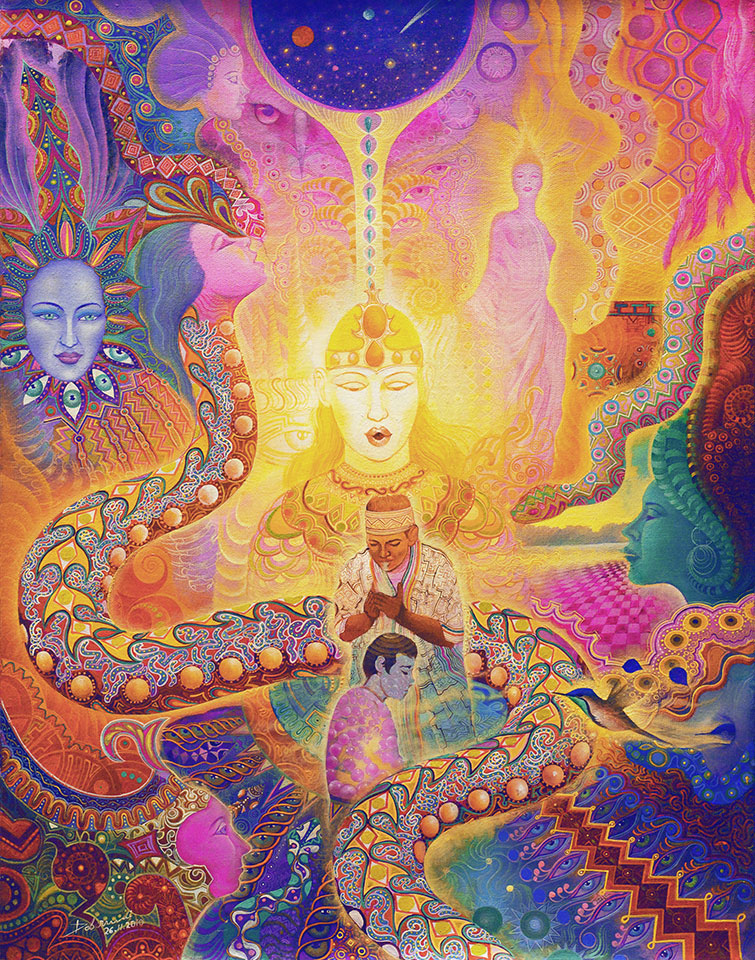

The Ayahuasca Visions of Pablo Amaringo (1999)

Amaringo is well known for his gorgeous visionary art. This updated (2011) edition contains a great deal of extra explanatory text for each visual image, and includes a great introduction from Steve Beyer. Amaringo explains the helping power of the doctores, or the invisible healers that accompany the yajecero.

Amaringo is also quite specific and confident about the overall cosmology of the inner planes, extending from material world, then charting the astral and causal planes dominated by exceedingly terrifying elemental forces and demons, and finally the pure spirit planes, that are the formidable goal of the innerspace traveler.

The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience by Benny Shanon (2005)

Shanon’s text is admirable in that it thoroughly Western in it’s analytical categorical fragmentation, breaking each ontological piece of the aya journey down bit-by-bit in an attempt to determine the imaginal essence of the quintessential magical medicine.

So instead of relating ayahuasca to the central shamanic religious history connotations as many others on the list have, Shanon’s scientifically rigorous reductive method of dissecting altered states of consciousness brought upon by the brew opts to deal with the rational qualitative categories of Time, Light, Open Eyed Visuals, Contents and Themes of visions etc.. He is less interested in overt theorizing, especially when it comes to occult matters.

Shanon’s slightly dry academic style is the only minor hindrance to an otherwise incredibly mind-expanding book on altered states of consciousness. He is also very open to the idea that the tea can potentiate an unprecedented unlocking of artistic skills, noted in his article “Ayahuasca and Creativity“.

Supernatural by Graham Hancock (2005)

Hancock’s now infamous book holds a special place in my heart in that it was the first text that introduced me to the daring concepts of interdimensional aliens and the similarity of half-human half animal hybrid spirits that he calls therianthropes, who populate the landscape of innerspace. These trickster spirits have the potential, if one is not on guard, for the very serious danger of malevolent spirit possession in ayahuasca ceremony.

Despite this, the book gave me the courage to conduct self-initiatation into the daunting mysteries of the vine, and for that I could not be more grateful.

Hancock’s European skepticism and critical eye astounded me with wonder at the ways in which a mere plant concoction could actually provide a daring psychonaut access to inner worlds that were not merely hallucinations, but shared interpenetrating invisible dimensions with veritable ontological beings conducting transhuman agendas.

This was the last of Hancock’s non-fiction works, and his ayahuasca influenced Entangled and War God are a prime example of what Rak Razam, Graham Hancock, psychedelic section editor of Reality Sandwich Jeremy Johnson and I have deemed to be entheodelic storytelling; a new art paradigm that is influenced by the intersection of altered states, the evolution of consciousness, entheogens, paranormal phenomena, shamanism, and metaphysics.

Aya Awakenings (2006) and The Ayahuasca Sessions (May 27th 2014) by Rak Razam

These two books stand as a great general introduction of the ceremonial use of the sacred vine for the Westerner. One of the highlights of Ayahuasca Sessions is Guillermo Aravelo admitting that the vine itself is the initiator, and that even for a Westerner a shaman may not always necessarily be needed for those brave enough to undergo the flickering DMT space alone.

Rak’s utilization of the introspective musings often found in the psychedelic-travel genre in Aya Awakenings is an equally fascinating counterpoint to the more conversational heart based approach found in Sessions. Awakenings is fast paced, stylish, and bites hard with a signature post-modern wit into the depths of complex energetic interactions found in power plant ingestion with both malevolent and healing spirits. Rak is also quick to point out there are shamans outside of the Amazon who do not in any way need entheogenic substances to interact and immerse themselves in the spirit world.

Razam’s distinct shamanic totem is the Monkey, and thus he is capable of poetically tree-hopping on a wide range of dauntingly heady intellectual subjects; from mapping the mind of God in neuroscientific inquiries incorporating 5-MeO-DMT with his companion gonzo scientist companion Dr. Juan, to musings on various metaphysical traditions, he is equally at home with geeky musings on Superman and his daringly honest fear of brujeria. Razam therefore dazzles the reader while he carefully instructs.

As a psychedelic medicine activist, his work with others in the community outside of these books is both critically engaged with and fascinated by the paradoxical cliches of ayahuasca tourism and Western pop-culture. Rak also runs a podcast exploring entheogenic sacraments and what he calls the “global shamanic resurgence” called In a Perfect World, which has included landmark ayahuasca pioneers Steve Beyer, Graham Hancock, Dennis McKenna, Jeremy Narby, and Richard Meech.

In a recent interview Razam conducted with Hamilton Souther, Souther laments on how there is a language popularized by the memes in ayahuasca culture that lack an ability to communicate the complexity of the actual long term use of the plant for serious spiritual guidance. He also gives details about an initiation in Peru conducted many years before the popularity of the culture, in order to overcome a difficult traditional apprenticeship lasting many years, eventually achieving the rank of curandero.

Both of these shamanic activists allow for a more dynamic view of the vine as a complex organic interaction with the holographic energy spirits who formulate after ingestion of the sacrament, in order to heal rifts in energy bodies. In this context, Icaros are magical songs designated for self protection against dark magical forces, or black magic as it understood in the Western (white) magical ceremonial tradition.

According to Razam and Souther, the overall purpose of ceremonial mastery in ayahuasca sessions includes such diverse goals of astral travel, chakra balancing, divination, and telepathic communication with spirit guides or shamanic power totems. These benefits occur well after the actual consumption of the tea.

The Jaguar that Roams the Mind: An Amazonian Plant Spirit Odyssey (2008) and The Shamanic Odyssey: Homer, Tolkien, and the Visionary Experience (2012) and by Robert Tindall.

Unlike the primarily left-brain dominated interpretations of found in non-fiction ayahuasca literature, what I like about Reality Sandwich contributor Robert Tindall’s writing is that he isn’t afraid to bring arts and the humanities into the ayahuasca intersection.

The visionary medicine communicates in a holographically global way, using the entirety of the brain to distribute individualized astral data transmissions of healing and divinatory content, so one would think the discussion of art and storytelling in relation to ayahuasca would be more common than it actually is.

In fact, as an unabashed Homer and Tolkien fan, his discussion of how psychoactive plants relate to sacred storytelling in Shamanic Odyssey, was a decisive influence on the formation of the entheodelic storytelling theory in my own ayahuasca influenced graphic novel trilogy KALI-YUGA, concerning the adventures of the time traveling wizard Abaraiis and he uses entheogens and elemental magick to defeat the seven Lizard Kings—masters of Kaos sorcery. We are first privy to a preview of his mythico-dissection skills in his penetrating look at Tristan & Isolde in Jaguar, a technique later perfected in Odyssey, wherein he distinguishes many ayahuasca-esque influences, including the veritable magical love potion.

In Jaguar, Tindall, who despite his affiliation with the tea describes himself as a practitioner of Zen buddhism, concisely explores what he deems to be the three central pillars of Amazonian shamanism: purging, psychoactive plants, and diet (not unlike the three pillars of Zen.) Tindall also discusses non-psychoactive plants that are used for the purposes of purging and cleansing on their own.

In a recent Vice interview, Tindall was carefully prodded with irony about his transformation into the shamanic power totem of the Jaguar, fortunately—for those who have actually ingested the medicine—this archetypal shift is very real and may provide a experientially raw, primitive energetic release that can not be tamed by materialist reductionism or pinned down by mere post-modern linguistic mind games.

Like Elenbaas’ and Weiskopf’s work, Tindall too deals with his confrontation with the metaphysics of masculinity and is forced to address the importance of balance and the natural power struggles found in father-son interrelationships.

The role of drug addiction treatment with the vine takes on a central role in the second half of the text, which is an increasingly important subject and can be supplemented by Labate and Cavnar’s recent academic tome The Therapeutic Use of Ayahuasca.

Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon by Stephan V. Beyer (2010)

Beyers excellent book and blog dedicated to ayahuasca and sorcery is perhaps the most thorough inquiry into the both light and dark magical practices of Upper Mestizo shamanism. It explores the reality of global brujeria, or the assault sorcery that is an all too common occurrence in the Amazon and other contemporary indigenous settings. Neil L. Whiteheads two nightmarish masterpieces Dark Shamans: Kanaima and the Poetics of Violent Death and In Darkness and Secrecy: The Anthropology of Assault Sorcery and Witchcraft in Amazonia are also worth checking out, in this regard. Beyer is also quite upfront about the possibilities of remote viewing with the tea, and documents visions of people doing various activities in the jungle miles away, which is later corroborated by eye witnesses.

Beyer was a long term apprentice in an indigenous tribe in the Upper Amazon that was relatively untouched by Western influence, which lends a certain credibility to his insights of the occult practices with master ranked curanderos and brujos. His account is unusual in that he has both female and male curandero teachers, as women are still actively discriminated in an typically male dominated shamanic lineage.

The duality latent in plant medicine is given fair treatment, as Beyer explains that the same plants used for healing are also used for equally nefarious purposes of black magic. The details of supernatural dart sorcery are discussed, which allowed him to be privy to the act of metaphysical death brought upon by the concentration of magical phelgm and invisible weapons. The duality of icaros, and the mythological origins of the sacred medicine also receive thorough documentation.

Singing to the Plants, like his previous work The Cult of Tara: Magic and Ritual in Tibet, is simultaneously academic and poetic at the same time. In contrast to Weiskopf, who sees the vine as primarily male dominated in energetic presence, Beyer’s in depth assessment peers into the infinite beauty and gentle majesty of the divine feminine as the spiritual essence of ayahuasca. But as Razam and Souther say, the plant gives it’s user an organic non-dual holographic laser energy scan reading—attuned to the unique specification of a persons vibrational field—in order to act as mirror of the initiate’s spiritual, psychological, and physical ailments.

Fishers of Men: The Gospel of an Ayahuasca Vision Quest by Adam Elenbaas (2010)

Next to Tindall and Flaherty’s emotionally naked renderings of personal inner journeys, Elenbaas is perhaps the most quietly poetic and subjective in his encounters with the vine, forgoing the need for any sort of scholarly detachment. It takes a big man to be as vulnerable about his own personal history as he is here, and for that I commend him.

Elenbaas also relates some soul-staining stories about the unfortunately active skepticism and downright condemnation from men of older generations in regards to some early experiments with various psychoactive medicines, who not surprisingly refuse to see any sort of positive implications in entheogenic healing work.

While much has already been said about the book being centered around father-son relationships, the visions recounted in ceremony are here amongst my all time favorite in their painterly vividness.

The Shaman and Ayahuasca: Journeys to Sacred Realms by Don Jose Campos Translated by Alberto Roman | Edited by Geraldine Overton (2011)

“The double of the shaman is the jaguar, because the jaguar is pure and sees with eyes of innocence.”

Peruvian shaman Don Jose’s down to earth and deceivingly simple narration of his interpretation of what makes a proper curandero opens up with a quip about not being able to pin down the mysterious spirit of Ayahuasca, whom he calls La Madrecita.

While a bit short, The Shaman and Ayahuasca contains some hidden gems about some subjects neglected in aforementioned books, such as the dangers of erotic dreams when following the dieta, and important notes on how ingesting aya allows the initiate to absorb and cultivate mariri—the spiritual power of plants.

There is some deep wisdom straight be gleaned here on the importance of sacred intent, purification, and healing, when working with any plants for the purposes of soul-travel and knowledge.

Psychedelia by Patrick Lundborg (2012)

While not exclusively about the sacred tea, Lundborg’s analysis of DMT and ayahuasca is amongst the most thorough and phenomenologically thoughtful that I have read. Lundborg coined the term UPT, the Unified Psychedelic Theory, which proposes to carefully isolate and map the Innerspace of the perilous journey of the cosmically courageous psychonaut.

Lundborg defines the four stages of the general trip model as: Sensory Realm, Recollective-Analytic Stage, Symbolic Level, and Transcendental Level—the last of which often coincides at the peak experience of the journey and pertains to the relatively common experience of ego loss.

Jimmy Weiskopf says in Yaje: The New Purgatory that drinking the tea in the jungle is “full of dangerous forces and the drinker fully enters this other dimension…wouldn’t it be better to isolate the ritual from nature instead of realizing it in the middle of the forest? Yes, in a way, but what would be the point?”

In Lundborgs book, he indirectly answers this important question by saying that it is in fact not necessary to go to Peru or Columbia in order to have a profound experience with ayahuasca, advocating something that has been criticized lately, which is 1st world, predominantly white or European, “bedroom shamanism.” But as Richard Meech has recently said, we are all indigenous to the earth, and everyone deserves a chance to find their own path with healing medicine. Guillermo Avarelo also relates, in Razam’s Ayahuasca Sessions, that the vine itself, rather than the curandero is the teacher and mediator of the chaos latent in the sparkling DMT spirit worlds.

Still, there are many traditionalists in aya culture who feel that a shaman is absolutely necessary in the process, and frown upon self-initiation for the solitary drinker.

Shedding the Layers: How Ayahuasca Saved More Than My Skin by Mark Flaherty (2012)

Flaherty stylistically minimal text opens with a horrifying description of demonic possession by a 30 black-vibed entity in the first ceremony he undergoes with the aforementioned Western curandero Hamilton Souther. It is a stark warning to those daring (or foolish) enough to handle psychonautic journeys without proper sitters and setting.

Mark is consistently self-deprecating throughout, and suffers from a severe form of eczema psycho-somatically triggered by sexual repression from his early teenage days of heartbreak and rejection brought on by a formidable (but nonetheless common) nervousness when communicating with females.

This skin condition became so severe that no topical medicine could do anything but temporarily mask the pain and burning itchiness, before he could stand it no longer and gave into frantically scratching until he was literally bleeding, with piles of dead skin laid to waste on the floor.

Flaherty’s breezingly short, heartbreaking tale is also a stark reminder that the sacred medicine may not always bring about miracle cures in an obvious way. Mark must undergo more than 200 sessions to in order to finally literally banish his inner demons and gain the courage to have intimate encounters with the opposite sex, and when he does, not surprisingly, the eczema is finally cured.

Rainforest Medicine: Preserving Indigenous Science and Biodiversity in the Upper Amazon by Jonathon Miller Weisberger (2013)

Ayahuasca research pioneers Graham Hancock, Dennis McKenna and Jeremy Narby have all raved about this recent publication for good reason. It stands as the best documentation of how mythological symbols and timeless shamanic lore as it is known by the Wairachina Sacha tribe of the Amazon is actually a direct reflection of metaphysical knowledge gained in the inner planes while astral journeying on the tea, which, for the secoya, means direct contact with celestial ancestors who have died long ago for advice on daily living and other spiritual matters.

In addition to this, Rainforest Medicine contains many specific insights into the subtle nuanced complexity of shamanic power animals, who are classified by various species—the infamous Jaguar totem having at least 5 different variations and solidifying the fundamental reality of astral shape-shifting as a form of magical power, so commonly found in ceremony. Weisberger spent 19 years (!) studying, drinking ayahuasca and absorbing the profound mystery of shamanism and rainforest medicine in order to learn these deep secrets.

———–

The most comprehensive ayahuasca and psychedelic research bibliography can be found at the searchable database at the MAPS website.

Honorable mentions not on the above list are Jeremy Narby’s The Cosmic Serpent (1999) and Peter Gorman’s Ayahuasca in my Blood: 25 Years of Medicine Dreaming (2010), both of which I felt were already too well known by RS readers. Also of note is Alan Shoemaker’s recent pithy publication Ayahuasca Medicine: The Shamanic World of Amazonian Sacred Plant Healing (2014), which is particularly interesting in that it compares different teaching styles of his apprenticeship with various curanderos, like Tindall and Razam’s work.

The comprehensive anthology Ayahuasca Reader: Encounters with the Amazon’s Sacred Vine edited by Luis Eduardo Luna and Steven F. White translated from over a dozen languages is probably also essential, though I have yet to fully gaze upon it’s bibliophilic beauty.

Gayle Highpine’s provocative article “Unraveling the Mystery of the Origin of Ayahuasca“, which is critical about Jonathan Ott’s classification of ayahuasca analogues (such as syrian rue x. acacia confusa aka Haoma) and the “DMT heavy” emphasis often found in psychonautic literature, is also a must read.

Aladdin’s magic carpet ride has also been speculated to refer to the experience of the desert based rue, whose spiritual essence has often been described as an “ice queen”. Haoma has a long history in Indo-Iranian religion stretching into distant antiquity, and its identity as the pegamum harmala was proved in Western academic literature by Flattery & Schwarz in Haoma & Harmaline (1989). Wahid Azal has posited that Haoma is directly related to Sufi mysticism (though of course not publicly admitted by Sufi Sheikhs) and the ability to connect with the ecstatic divine feminine emanation of the non-dual God-head, a central goal of apprenticeship with visionary plant that could still use more emphasis.

The ayahuasca vs. anahuasca debate in the sub-culture is an interesting subject that Patrick Lundborg (author of “The Psychedelic Bible” Psychedelia) and I discuss in our forthcoming interview. The myth of the Tree of Life may in fact be a veiled DMT reference, due to the prevalence of various tree barks throughout the globe containing high yield. One wonders how many other ancient religions and gnostic sects had similar alchemical concoction inspirations that we simply have not yet found direct evidence for.

Every one of the above mentioned texts are critical in an appreciation of the central mysteries of the vine—with direct experience taking obvious precedent—as veritable translinguistic spiritual mysteries may never be pinned down by mere words.

[1] Toé, the ‘Witchcraft Plant’ That’s Spoiling Ayahuasca Tourism, and From Rape To Forgiveness and The Journey Home by T. R. Waters. Perhaps self-initiation via safe and legal sustainably grown practices is an answer to the socio-economic driven dangers of ayahuasca tourism.

[2] On physical proof of brujeria and it’s fundamental relationship to indigenous politics see Beyer’s article Fourteen Dead Shamans. See also Neil L. Whitehead’s Dark Shamans: Kanaimà and the Poetics of Violent Death and In Darkness and Secrecy: The Anthropology of Assault Sorcery and Witchcraft in Amazonia. For a critical bibliography, see Ayahuasca Religions: A Comprehensive Bibliography and Critical Essays by Beatriz Caiuby Labate, Isabel Santana de Rose, and Rafael Guimarães dos Santos. For some in depth reflections on the dark male archetype Graham Hancock calls “the magician” see his article Letters from the Far Side of Reality.

[Image “Shaman Transformation” by Anderson Debernardi]