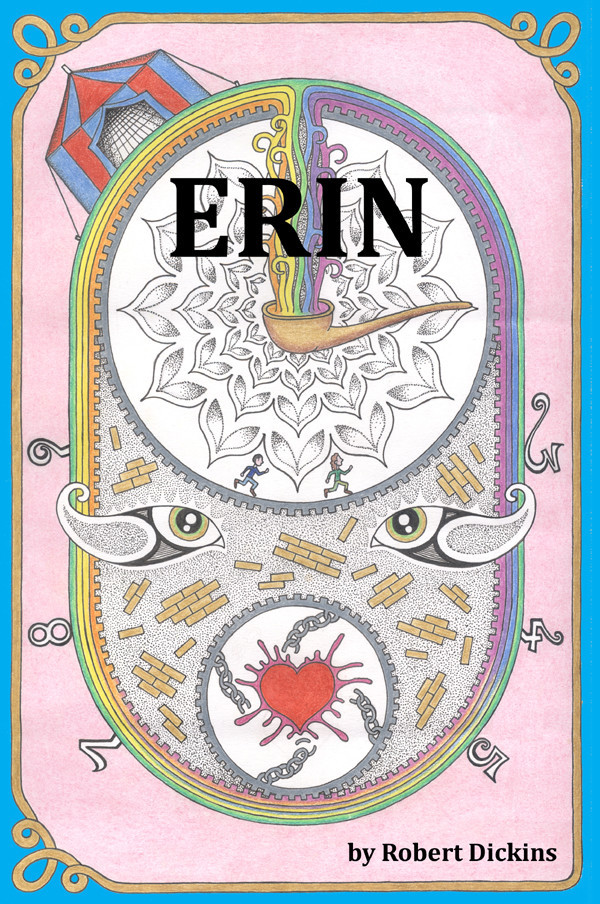

Erin was a unique book for me. Maybe it was because it was the first novel I’d read about festivals. It could’ve been because of the sheer amount of psychedelics descriptively ingested across the novel, but whatever it was, I hadn’t encountered a story quite like this one. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style, Erin’s mysterious plot unravels thread by thread as the colors, lights, and morphing faces of the festival go-ers whiz by on the narrator’s tongue. I spoke with author, Robert Dickins, who is also the editorial director of the publisher PsyPress UK, about Erin and writing psychedelic literature today.

Jeremy Johnson: Why write a novel about a psychedelic festival?

Robert Dickins: The old adage is that you write about what you know. I spent the best part of a decade reviewing music and arts festivals for various publications – the good, the bad, and the darn right weird. My reviews always attempted to answer the question of ‘what have I been thrown into?’ and unpicking the carnivalesque and psychedelic atmospheres, ones I found myself bejeweled in the middle of, gave me the opportunity to re-create what I hope is a very trippy pastiche of occasions.

With any festival – but particularly ones seen through eyes that sparkle – there always seems to bubble up the paradoxical sense of being expressively free, yet remaining enclosed within the space of the fayre. I wanted to try and capture this with Erin, and it felt that the novel form lent itself very easily to this sort of exploration. A mood of fast vibrating emotions, changing by day and night through the many various micro-fields, can be allowed to spin out, yet remain bottled – and to an extent controlled – within the turning pages of a novel.

Can festivals be places for major, psycho-spiritual breakthroughs? Have you experienced that – or in other words – is this book part autobiographical?

The simple answer is yes. Indeed, I think almost any setting could potentially be a place for ‘major, psycho-spiritual breakthroughs’. It’s not always just a case of preparing a set and setting, sometimes you can’t arrange yourself or the world as you would wish, and that element of chaos creates the possibility at every turn. There is, of course, something particularly rarefied about a properly performed festival – a theatrical show where the players’ dance can easily whirl into an ecstatic, psycho-spiritual flood.

However, although it certainly has its place, I’m not hugely fond of the term ‘breakthrough’. It implies a sort of universal, or fallen, nature, which we each must battle through, the never-ending cycle of healing for growth. My own experiences, the psycho-spiritual ones, I would describe – though not ideally – as recognitions. They are sacred and mundane, not opposed but of different degrees.

I’ve laid-out almost sparko and definitely spaced out, flying the cosmos, and recognized the true meaning of a random cliché I’ve banded about wrongly for years – profound in its own weird, little sense. I’ve also been in the midst of a sweaty, swelling number of people in a dance tent, and recognized – through feeling and emotion – the infinite complexity that made that moment actualize. It has always felt to me that psycho-spirituality is about the ability to remain open to experience and recognition, not about the movement from closed-to-open.

So, is the book autobiographical? Only so far as I could invest the literature with those qualities in experience, of recognition and realization, that I’ve come to cherish in my own life. Putting experiences in an order, however, with the spice of a characterized individual psyche to filter them through, is the storytelling art at work.

Do you think certain literature can help induce altered, or visionary states? Because there are certain pages in Erin that did that for me.

Well, I’m very glad to hear you say that, as it was certainly my intention to put the reader into a shared altered state. I think there’s a question of empathy here, a literary contact-high if you like. People have attempted, in a whole manner of ways, to put the psychedelic experience across on paper, and it’s notably tough (which hasn’t been helped by the early adoption of mystical discourse – ineffability is not a great friend to the prose writer!)

So far as literature goes in general, I suppose there’s two types that if structured and employed well can really take the reader into a spin themselves. On the one hand, as in Erin, the first person narrative is very good at jumbling up the ‘I’ of narrator and ‘I’ of reader, and if the text is fluid enough then it provides a really thorough passageway to be enthralled by. This might possibly work with a second person narrative as well, although I’m yet to read a succinct psychedelic narrative of this type.

On the other hand, there is the guide or mantra text; the most obvious psychedelic ones being Leary’s Psychedelic Prayers and The Psychedelic Experience. These are obviously a lot more hands on and practical, but they do go to show how text can play a very active role in manifesting certain experiences under the influence as well. The text and the world of sense can easily be collapsed in on one another.

What’s significant about publishing psychedelic literature today?

The obvious answer is of course the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ that is underway. What is interesting is that this phrase is really bringing the word ‘psychedelic’ back to its psychiatric root, shedding some of the cultural layers that it has accumulated over the past 50 years. The renaissance refers to an increase in scientific research, and not to the culture that surrounds these substances, which has never gone away and has indeed – through alchemy and other endeavours – kept the psychedelic flame going in the meantime.

I wrote a university thesis on psychedelic literature a few years ago that drew a distinction around ‘psychedelic literature’ as pertaining to certain psychiatric and psychological approaches to the trip experience. These medical monographs, such as Ward’s A Drug Taker’s Notes and Newland’s My Self and I, disappeared in the mid-sixties along with the research. Now they are starting to return. For instance, we featured a couple of brilliant narratives in the Psychedelic Press UK journal from the UK’s first official LSD trials in forty years.

However, unlike 50 years ago, when the culture rose out of the literary-scientific circles of the 1950s, today they are both in full swing. The significance of psychedelic publishing today is that both the science and the culture need to be catered for. They both feed each other to a degree, although sometimes they are antagonistic. What we aim to do in publishing is to give them both room to breathe – society at large is need of both the materials and the mischief. Also, from an historical point of view, these events – I believe at least – definitely need to be catalogued, not just for posterity, but for the importance and complexity of what this juncture in civilization feels like. The psychedelic experiences of today promise to have a very large influence on the future indeed.

Who do you think Erin will connect with?

I think Erin will connect broadly with anyone who has experienced serious mental catastrophe – through psychedelics or otherwise – as well as those people who have played and caused mischief in the festival and counterculture scenes. Although it is a darkly psychological narrative, it also attempts to capture some of the playfulness and colour of the trance/free party and festival movements. Moreover, anyone who likes a good read!

So, who is the elusive Erin, anyway? What is she really about?

Erin is a memory, a phantasm, a guide, a pathology, and a love. Most importantly, she is the ambiguity and chaos of one’s personal life, out of which the web of wyrd will arise. In the novel she is the anchor that connects fast-paced sensual bombardment, and to my mind she represents the quintessence of the psychedelic experience that cannot be straightforwardly formulated in words, but which deeply pervades all the moments of the psychospiritual and hedonistic mixed-media-mash-up.

Photo credit: Andy Roberts