But it—this timeless and yet ever-changing Event—was something that words could only caricature and diminish, never convey. It was not only bliss, it was also understanding. Understanding of everything, but without knowledge of anything. Knowledge involved a knower and all the infinite diversity of known and knowable things. But here, behind his closed lids, there was neither spectacle nor spectator. There was only this experienced fact of being blissfully one with Oneness. In a succession of revelations, the light grew brighter, the understanding deepened, the bliss became more impossibly, more unbearably intense. “Dear God!” he said to himself. “Oh, my dear God.” Then, out of another world, he heard the sound of Susila’s voice. “Do you feel like telling me what’s happening?”

The year was 1962 when esteemed English novelist and social satirist Aldous Huxley penned the final pages of his last book, Island. The scene depicts the emotionally twisted and morally conflicted English journalist, Will Farnaby, as he resolves his issues through the use of Moksha medicine- a customary tradition in the idealist’s society which he has found himself. The medicine Huxley speaks of is more commonly known as magic mushrooms, containing the psychedelic compounds psilocybin and psilocin. A matter of months after penning this, his final work, Huxley passed away peacefully with his loved ones as a standard dose of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, or LSD, coursed its way through his body and mind.

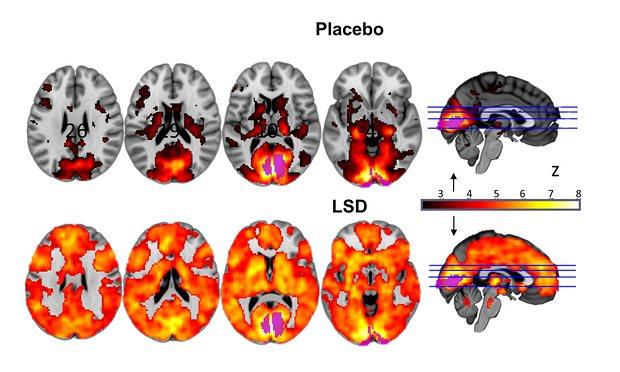

Earlier this year, following a slowly-ceasing hiatus of psychedelic studies, psychedelic therapy with these substances was thrust into the spotlight once again. Professor David Nutt and Dr Robin Carhart-Harris studied the effects of LSD on the human brain under an MRI scanner. The study found that functions of the brain responsible for vision, movement and attention become intrinsically connected, while the parts of the brain responsible for reinforced patterns are disrupted. According to Dr Stephen Bright, Vice President of PRISM (Psychedelic Research In Science and Medicine), an Australian organisation dedicated to the study of psychedelics, this disruption of patterns provides hope for those suffering depression.

“Psylocibin and other psychedelics allow people to see things in a different way and many people with depression have very deeply entrenched beliefs. So it allows them to see things from a different perspective and create new neural pathways that then are an alternative to the entrenched belief that’s been perpetuating their depression,” he said.

Studies like this have been occurring throughout the Western world for decades, with strong evidence that psychedelic medicines are the most effective way to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and end of life anxiety. Yet Australia’s overtly-conservative view on drugs appears to be preventing progressive research to take place.

Almost all native cultures have integrated psychedelic healing into their way of life, with the Amazonian Ayahuasca brew as well as an ergot tea used in ancient Greece both examples of psychedelic compounds used in hundreds of religious ceremonies throughout history. However, since the War on Drugs began in 1971 in response to the counter-culture movement of the 1960s, Western civilisation has turned its back on the idea that psychedelics could have any medical benefit, despite over one thousand peer-reviewed studies in academic journals showing the positive effects of drugs such as LSD, Psilocybin and MDMA. As a result these drugs were classed in the most restrictive substance category; Schedule 1 in the USA and UK, and Schedule 9 in Australia.

Many believe cult figure and Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary to be liable for the illegality. “Leary got a bit excited about it all and knew that there was something special here and thought it should be accessible to everybody before sort of more rigorous testing was done, and in turn what that led to was the counter-culture movement, and as a response to the counter culture movement Nixon started the war on drugs and LSD and other psychedelics were the first in the cite, so all the research shut down as soon as the war on drugs started. And then everything went quiet,” Bright says.

The negative stigma of psychedelic drugs is changing throughout the Western world, however, as studies and therapies are being conducted in order to treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and end of life anxiety with outstanding results. Prominent New York psychologist and author of Psychedelic Healing: The Promise of Entheogens for Psychotherapy and Spiritual Development, Dr. Neal M. Goldsmith, states that there is a changing view of psychedelics in the USA due to astoundingly promising studies by university medical schools such as Johns Hopkins, NYU and UCLA, that abide by “uniformly excellent” methodologies.

“The two substances in this beautiful horserace to become rescheduled from Schedule I are MDMA; which is being used as an adjunct to post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) psychotherapy, and psilocybin, which is being used to ease end-of-life anxiety in terminal cancer patients. So my god! What could be more convincing and poignant and beautiful and difficult to oppose, than helping somebody who will be dead in six months? And you’re going to what? Hold back medicine from them, even experimental medicine? They’re going to be dead in six months, you can’t!” He says. “And then of course the results of the people talking about how it feels to lose their fear of death or how the mother feels when the daughter died peacefully, it’s just heartbreaking, it’s very, very, very powerful – and very influential. And then there’s MDMA and it truly works! How are you going to oppose giving MDMA to a woman who was raped by her uncle when she was two and hasn’t been out of the house for 25 years? And then when you provide MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to people like this, and they’re cured, they can go shopping now. Well, how are you going to say no to that? Especially when the data are so strong and the testimonials are so moving and beautiful?”

Whilst not government-funded, psychedelic research has been approved in the USA since the first Bush administration, and has seen a healthy research environment where psychedelics have been treated just like any other investigational research drug. According to Rick Doblin, the head of the USA’s Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), drugs such as psilocybin and MDMA will be rescheduled for medical use in approximately 8 years.

The ingrained stigma towards psychedelic drugs in the Australian scientific community, however, may cause rescheduling of substances to take more than double this time. “Our experience has been that it’s not so much the regulatory constraints but the conservativism within the academic community. No senior researchers in Australia want to touch this with a ten foot pole,” Dr Bright explains. “We’ve actually, we’ve submitted a proposal to conduct research at Deakin University to the human research ethics committee, but before the research even got to the ethics community the… I could get this wrong but the deputy vice chancellor or somebody very senior within the university stopped it going to the H res. [sic: Human Research], saying that that Deakin wasn’t going to be conducting this sort of research at their university. So it’s risk aversion.”

Deakin University refused to comment on the matter, a reaction shared by almost all within the Australian research community. The media team of Dr Glenys Dore, Associate Investigator and consultant psychiatrist at the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, agreed to the interview, yet when the interview was scheduled Dr Dore’s secretary stated that she did not want to comment due to increased scrutiny on the subject, and she wanted to remain neutral as to not misrepresent her workplace. Dr Stephen Jurd, addiction psychiatrist at the Northern Specialist Centre similarly agreed to an interview before abruptly declining due to the subject matter. As well as this, despite releasing a document studying the rise in LSD use in 2013, and earlier this year re-publishing online a 2010 study on the health and psychological effects of MDMA, the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC) refused to comment, stating “…it’s [psychedelics] not our area of research.” This avoidance of comment shows the effect that discussion of the topic may have on a doctor’s reputation in Australia.

“I’ve written my PHD on it and it’s called the pathological paradigm,” says Dr Bright, “So all of the money that goes into researching illicit drugs is focussed on supporting the notion that they are harmful to justify the legislative framework we currently have which prohibits their use. And so it’s very difficult, in fact nearly impossible, to get government funding to conduct research on illegal drugs that might show positive effects, because that sits outside of that pathological paradigm where drugs are seen as pathogens and are dangerous and people that use them are reckless and irresponsible people, and if they were exposed to these pathogens they might experience the disease of addiction and so on and so forth. So because that’s the dominant paradigm within Australia. Within the academic community who are studying illicit substances, it makes it very difficult to conduct alternative research looking at more positive things. Then this moves through to the pill testing stuff that’s happening at the moment, I mean the government’s not going to be throwing a lot of money at pill testing. It’s all going to be done by people that are very passionate about reducing potential for people experiencing harm at dance events that put their time and resources into it because the government doesn’t want to be seen as going soft on drugs.”

Psychedelics such as psilocybin and LSD have no physical side effects, and it is essentially impossible to overdose off these substances, and despite the common belief that they will ruin one’s brain, these psychedelics actually promote the growth of brain cells and have no harmful effects. Yet while the study of such substances in Australia remains limited, pharmaceutical psychiatric medicines are often a go-to treatment for depression, anxiety and PTSD, despite the common risks of overdose, organ damage or anti-depressant induced chronic depression.

“In my experience of suffering with depression for many years I used two forms of anti-depressants, I found both Flouxetine and Cymbalta, members of the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibiter (SSRI) class of anti-depressant medications, to be not particularly beneficial as a long term treatment of depression. While they did help get through some particularly rough patches of my life, they came at the expense of an inability to feel much at all. While the lows weren’t as low, the simple aspects of my life that still occasionally brought me pleasure no longer achieved the same levels of satisfaction. It was as though your moods were capped between a select range of melancholy and adequate,” says a UNSW psychology student who wishes to remain anonymous.

“But slowly I became aware that no amount of medication would be a long term solution to a mental condition, and although sessions of CBT, hypnosis and other alternative therapies seemed to bring me no closer to the root cause, I began to see SSRI’s were not the solution.”

“Coming off the anti-depressants were particularly bad, the first time I couldn’t sleep, woke up with the most vivid nightmares I have ever experienced, with sweats or shivers, vomited most mornings and just generally did not feel myself.”

Dr. Goldsmith believes that the use of these traditional pharmaceutical psychiatric medications can be a useful palliative tool to treat symptoms of these illnesses; he does not believe them to be a long-term solution to the problem. While not openly encouraging the use of psychedelics himself, Dr. Goldsmith believes that therapy following a “beautiful, powerful, enabling type of experience” with a psychedelic is a valuable tool in psychological development.

“People come to me all the time who have taken psychedelics and I say to them alright, I can’t recommend you use them, but if you use them anyway, try to take them the day before you see me. So, if you do it on a Wednesday make an appointment to see me on a Thursday. That way, I get to talk to them the next day when they’re fully opened up. When they’ve had their blissful experience, or their difficult experience, and I can really make good progress.

“I work with them on developmental issues, as always with clients. Development is like – you come up to a wall and you hit your head against a wall. It looks like it’s going to go on forever, but then, a miracle occurs, a quantum leap, and you’re up on the next level of complexity and conscious awareness. And from that vantage point, you say ‘oh that was obvious,’ but it wasn’t so obvious when you’re hitting your head against the wall – depressed or anxious, the last thing you want to do is give them a psychiatric medicine like Prozac because you kill that process,” he says.

In Australia, one of the main focuses of psychedelic research is the treatment of PTSD through MDMA, which has proved successful in all current studies. Dr Bright explains that order to receive support for this study PRISM are trying to gain widespread awareness of their work with soldiers who suffer from PTSD. “There needs to be a window of opportunity and we’ve tried to leverage that by focussing on war veterans and the fact that more people are dying from suicide than from the previous wars that Australia has been engaged in, and by providing them an alternative to the current treatments which clearly aren’t working for everybody because of this high suicide rate… that’s where I see people are missing an opportunity to receive a treatment.”

Following a study of 12 cancer patients struggling with end of life anxiety, Swiss psychiatrist Dr. Peter Gasser became world’s only doctor legally allowed to give patients LSD to assist with their therapy. He, like Dr. Goldsmith, believes that the psychedelic experience is a catalyst for the user to enter a different state of consciousness. Discussion and therapy following this experience makes for an effective treatment for conditions such as PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder and cluster-headaches.

“It’s basically the same when you have a new cancer treatment-medication for cancer which is not yet in registration- then authorities can allow, in special cases, a treatment with non-registered drugs and they look at lsd as a non-registered drug. So they can make exceptions. This is our luck and it means also that authorities are mainly willing to support this kind of treatment,” he says.

When asked about the side effects of his treatments, Dr. Gasser states a user may have a bad experience leading to a psychological crisis if not properly dealt with. He assures, however, that this has never occurred in a controlled environment and there has not been a negative experience in his work. On a physical level, he says, LSD is a non-toxic substance taken in small doses (a standard dose is approximately 100 micrograms) and therefore has no physical side effects.

“My hope is that one day it will be a kind of, it can still be a narcotic drug but it may be not legal but can be used in medicine. Like morphine which is not legal, it’s a narcotic drug but it can be used in the medical setting. Will it be legal or a registered drug again? I think that will take really a long time. I dont think i will experience that during my lifetime. But I think in 10 years it will be possible on a larger scale to do treatments with these drugs.” He says.

One case of successful psychedelic therapy is Katia Honour, an Australian visionary artist and supporter of psychedelics following treatment for her sever PTSD with Ayahuasca, a South American tea which orally activates the psychedelic Dimethyltryptamine (DMT); a compound found in the brain of most animals believed to be released when a creature is born, when they dream, and when they die.

“After a near-death accident, I tried everything Western, Eastern, scientific and spiritual. I had one of Australia’s best psychiatrists, and even she could offer no reliable, guaranteed cure for PTSD or even ascertain how long the condition would last,” Ms Honour says. “Then I stumbled across the research papers on the shamanic use of the entheogen, Ayahuasca. I was significantly better after just one session and had a noticeable shift in my happiness and confidence.”

“After one session, I was able to feel safe, happy and connected – which was very alien to me. I walked onto the street and instead of paralysis and blood noses, I cried with joy at the human kindness and blue skies I saw, as though for the first time. It gave me a hopeful way of seeing in my world and a context for my trauma as initiatory rather than just ‘broken’.”

Despite her support and experience with psychedelic medicine, Ms Honour still stresses that responsible use of these substances is vital. “Many ‘use’ these substances as recreational drugs, in physically and psychologically unsafe environments, or worse, at a party where they have no boundaries, intention or sense of healing intention and purpose.

Although there is a long way to go and many more studies to complete, the worldwide view of psychedelics are shifting from a dangerous drug destroying our youth, to a safe and valuable psychological treatment. Australia has a long way to go when compared to the rest of the world, but as international perceptions shift so will the local medical and scientific community.

“I think there’s light at the end of the tunnel and it’s very bright,” says Dr. Goldsmith. “I think it’s clear there’s an endpoint, I think we’re over the hump, I really do. I think we’re on the downward side of the hill.”