On March 20-22

at Brown University, the Language Creation Society hosted the 3rd

Language Creation Conference,

a tribal gathering of self-described language geeks, (a label I proudly wear

along with my newly acquired LCS pin, with its symbolic Tower of Babel).

Conlanging

(from constructed language) is obsessional, hermetic, prolix, and

involves Deep Chops, combined with the spirit of play. It’s geeky, even cosmically geeky, as Jeff Burke (aka White Thunder),

creator of the Central Mountain Languages, puts it.

Linguistic Diversity

Linguistic

diversity is falling in parallel with biodiversity, “faster than ever before in

human history”, according to Tove

Skutnabb-Kangas of the University of Roskilde. Europe is the poorest

continent in linguistic diversity, while “Indigenous peoples, minorities and

linguistic minorities are the stewards of the world's linguistic diversity.”

Nigeria alone has 410 languages; Papua New Guinea (850 languages) and Indonesia

(670) between them hold 25% of the world’s languages.

Figure 3: “Fight Linguistic Extinction–Invent a Language!” (David Peterson's Kamakawi script)

Linguistic diversity and

biodiversity are correlated; when one is high, the other generally is as well.

But languages are disappearing faster even than butterflies–except in the

conlang community, where linguistic creation and experimentation is bubbling up

out of a primordial soup of natlang (natural language)

parts, with plenty of mutations, variations, and hybridizations, as well as new

orthographies (written systems that may or may not represent the sounds of a

language). Emergent forms of languages–visual, both 2-dimensional and

3-dimensional, gestural, sculptural, languages with no spoken form, and lots of

alien languages, are all part of the mix.

The Shakespeare of Conlanging

J. R. R. Tolkien

is, of course, the Shakespeare of conlanging. His essay, “A Secret Vice,”

details his own experiences and speculations about language creation, which

possessed him from an early age. Many, if not most, conlangers began some form

of the activity in childhood. Tolkien calls conlanging “a new art, or a new

game” and indeed, the activity is perfectly suspended between these impulses.

And secrecy plays itself out in various aspects, beginning perhaps with the

delight of children in having secret languages and societies to bond their

group. Later come secret scripts for maintaining the privacy of journal

writing.

Stealth-langs

Deena Larsen’s

Rose language/code serves such purposes. In her own words: “It is based on

English, but has 75 characters. Each letter has variations that connote

emotion. When I write, I unconsciously use these forms. Then when I

reread, I find out what I was feeling. Then I can get to my "inner

thoughts."

Figure 4: Deena Larson's Rose

A wry take on

the secrecy–or privacy–of conlangs from “Leah” on the

alt.language.artificial list: “As for a lang having interest to someone other

than the creator, that can vary with time. When I finished my first conlang, I

offered to teach it to people I know, and they refused, UNTIL I started keeping

my personal journal exclusively in my conlang. THEN, the interest started. Of

course, they want to spy on my most private thoughts. Therefore, my conlang

became my stealth lang.”

Stealth language

is also Tolkien’s term. For him, a stealth language can “satisfy either the

need for limiting one’s intelligibility within circles whose bounds you can

more or less control or estimate, or the fun found in this limitation. They

serve the needs of a secret and persecuted society, or the queer instinct for

pretending you belong to one.” (Think pidgins, creoles, slave languages).

Tolkien began the Silmarillion, the first parts of his “mythology for England”

and the mythical basis for The Lord of the Rings, during WWI, in hospital,

recovering from the injuries and horrors of trench warfare in the Battle of

Somme.

Bradford White’s

conlang story is a strange parallel. His adventures in conlanging began as a

child, inventing a language to pass secret notes in school. This impulse

resurfaced in Marine bootcamp, with exposure to the special military jargon; he

and his buddies made up more, for their own uses. His conlang Friivoliik came

about while recovering from war injuries recently at Camp Lejeune, including

snapped tendons in his foot and a nasty case of flesh-eating staph infection

advancing up his leg. “While bed ridden, I tried to write down the things that

had happened to me, and exactly how they made me feel. Some of the things that

I had been through, and some of the things I had seen were difficult to deal

with, and I was searching for a way to more accurately express myself.” His

language includes a special “emotive case” which expresses different relations

to emotions experienced, relating to their intensity. As he explained to me,

sometimes it is not strong enough to say merely “I felt this;” he has a means of expressing the

quality of an emotion that utterly possesses one, the difference between saying

“war gives me depression” and “war gives me to depression.”

Language and Mythology

Tolkien’s

Silmarillion is the mythology of his Elvish languages, Quenya and Sindarin.

For Tolkien, language and mythology are deeply intertwingled. “I must fling

out the view that for perfect construction of an art-language, it is found

necessary to construct at least in outline a mythology concomitant. Not solely

because some pieces of verse will inevitably be part of the (more or less)

completed structure, but because the making of language and mythology are

related functions; to give your language an individual flavour, it must have

woven into it the threads of an individual mythology….The converse indeed is

true, your language construction will breed a mythology.”

In contemporary

conlanging, this principle is in force in a significant number of conlangs:

they come hand in hand with the imagined worlds in which they communicate.

Sally Caves, a professor of English at the University of Rochester (as Sarah

Higley), whose creation of Teonaht, a language and a world, began at age nine,

expresses this principle eloquently: “Those unbitten by this bug will

undoubtedly want to know why we do it: why invent something so intricate, so

involved, that only a few people, maybe even no one, could ever share in its

entirety? To begin such a thing is whimsical at best, but to persist in it is

surely madness. However, I'm not alone in my pursuit. The discovery of Conlang, a listserv devoted to glossopoeia or the

artful construction of languages, introduced me to a world of compatriots who

share my love of language–not just the natural languages, but the

experiments one could make with syntax, morphology, typology, lexicology,

historicity, and myth. . . . glossopoeia is like building a strange, new,

mythical city. You start with the foundations and move up, stone by stone. Or

sometimes you start with the roof and work down. Sometimes your paths are

crooked, others straight; sometimes you erect cathedrals, canals, and bridges.

Sometimes you tear everything down and start over. Gradually it takes on a

character and populace of its own, and all its own rules, and you come to know

its streets and houses and people as unique. You have relexified your world.” (emphasis mine) Sally (as Sarah

Higley) is the author of Hildegard of

Bingen’s Unknown Language. Conlanging, as well as music, was part of Hildegard’s

productive frenzy.

Ideal Languages, Differently Dreamed

If Tolkien is

the Shakespeare of conlanging, surely Paul Varkuza is its Rimbaud. A

synaesthete with plenty of attitude, Varkuza claims to have named himself after

his language, Varkuzan, “because

he himself and his work is only an extension of the greater idea(s) that

Varkuzan represents.” To him, conlanging is a laboratory akin to a psychoactive

substance where new versions of reality (not just descriptions) can be created.

An intimate connection with one’s conlang indeed. Varkuza has utopian

intentions of “complete objectivity” yet combines metaphorical as well as

mathematical and technical means to accomplish his ends.

Andrii Zvorygin

states, “a formal language that unites all the ideas of humanity (math,

science, religion, society) is my goal.” He is also “in the process of founding

a religion with a universal conlang as a grand unifier.” Sound like Hesse’s

Glass Bead Game?

Sai Emrys,

founder of the Language Creation Society, posts a many-year, much revised “Design of an Ideal

Language.” In his own words, “I make no presumption that my particular

desires are in any way objectively best; only that one can objectively take a

look at some particular set of desires, make tradeoffs where needed, and then

go about fulfilling them optimally in a systematic way. There are therefore an

infinite possible set of perfect languages, for each of an infinite set of

desiderata.”

Umberto Eco

calls it, “The

Search for the Perfect Language.” But of what does linguistic perfection

consist? The answer is as old as the mythology of the Tower of Babel which

considered linguistic diversity a bug, not a feature. One “perfect” language?

Or many, each with their own perfections? And on something like this point,

(and many others too subtle or too noisy to detail) the Great Schism occurred

(circa 1999) on the conlanging list, with truce attained by splitting into two

lists, conlangs and auxlangs (auxiliary languages, like Esperanto) and only

occasional border raids by proselytizing Esperantists and the like. (You can

tell which list has my loyalty.)

Linguistic chops

Deep linguistic

chops–really knowing the rules–are Sylvia Sotomayor’s launching pad

for breaking them with her conlang, K?len.

“Learning about universals made me wonder what a language would be like that

violated them. So K?len became my laboratory for exploring the line

between a human and a non-human language. There are a few inherent difficulties

to this task. For one thing, since we haven't found any intelligent aliens,

there are no non-human languages to look at for comparison. So, my strategy was

to take a universal and violate it.” K?len replaces verbs with a closed

class of “relationals” that perform the syntactic function of verbs. Sotomayor

has created, out of an early fascination with all things Celtic, several

beautiful K?len scripts.

Figure 8: Kelen regular script

Certainly one of

the most complete–and sophisticated–aesthetic realizations of an

orthography (Tapissary itself is coded to English) and conculture is found in

Steven Travis’ work of the past 30-plus years. A pictographic language, Tapissary, inspired by American Sign

Language, has about 8,000 characters. “I enjoyed the beautiful movements of

Sign Language and experimented with stylizing motion into script,” Travis

reports. Venticello is a miniature ceramic village, constructed in his

backyard over many years. There are also illustrated journals, ceramics, and

sculptures. Tapissary 101

(YouTube) is a timeline of the language’s development. Hieroglyphic

Collages were shown at the Conference exhibition, and they are stunning.

Pictures of Venticello are inserted into the glyphs; the glyphs become windows

onto the world. These were shown at the Amos Eno Gallery in NYC in May, 2008.

Figure 9: Sylvia Sotomayor in Kelen ceremonial vestments

Conlanger Games

While conlangers

have not yet erected a Rosetta stone, perhaps because a stone would hardly

contain this Cambrian explosion of linguistic diversity. Imagine a wall with

hundreds, yes, hundreds of symbolic systems side by side, each with their

version of the Babel text,

the Biblical passage about the erection–and fall–of the Tower of

Babel and the confusion of languages henceforth among the human races. This is

the text most often translated by which conlangs can be compared. While

auxlangers dream of the one perfect language that will unify the planet and end

all communicative confusion and misunderstanding, conlangers tend to be

pro-Babel, taking freedom of speech to new levels. Noetic license, indeed.

Another group activity among conlangers are the relays–like the

children’s game of telephone, only translating an original text through several

conlangers’ languages. More games: at the conference, Jim Henry’s Glossotechnia, a

conlang creation card game, was played. I’m not even going to try to describe

it, but here are the conlangers in the heat of play.

Alien Languages

Conlangs such as

Jeff Burke’s Central Mountain Languages exist in alternate histories of Planet

Earth. Once you move off-planet, say, to the second planet of Alpha Centauri

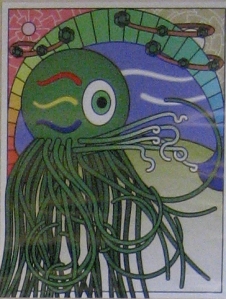

A, entirely new possibilities open up. Denis Moscowitz’ Rikchik language, for

instance. “The rikchik body consists of a large (~2 ft. diameter) sphere,

which contains almost all the rikchik's organs, supported by 49 long (~6 ft.)

tentacles. In the front of the sphere is a single eye with a circular eyelid.

The 7 tentacles immediately below the eye are shorter and lighter, and are used

for talking…” thus, Rikchik is a signed language, with no sonic component, and

written Rikchik is a speechless orthography. Rikchik is also unusual as a

cooperative venture by Denis with his brother Marc. Pair/group conlanging is

very much a rarity. For more information, contact the Rikchik Language

Institute.

Figure 14: Rikchik morphemes, based on tentacular formations

My own work in

the Glide language is similarly

extraterrestrial, transdimensional, visual–with no spoken component–and

produces dynamic as well as static forms of writing, in two

and three dimensions (LiveGlide). Its myth of origin lies 4000 years in the

future when the language was given to the Glides by the hallucinogenic blue

water lilies they tended. Glide began as a gestural language, later written

down to become the basis of a game played in mazes made of Glide glyphs. The

story is told in the novel, The

Maze Game. Some of the theory around Glide is on my Xenolinguistics website, a sketchbook for

current Ph.D. work on linguistic phenomena in the psychedelic sphere.

Conlang: The Movie

It had to

happen, and out of Iceland: Baldvin Kári Sveinbjörnsson is the writer/producer

of a short film, Conlang,

created as part of his MFA work in film at Columbia. Sveinbjörnsson uses the

Uscaniv language created by Kári Emil Helgason as a language of love in this in

turn delightful, campy, touching and hilarious (at least to conlangers) story

of young love in the time of role playing games. The movie is directed by Marta

Masferrer, also at Columbia.

The Exhibit

A highlight of

the conference was the poster exhibit. Part of the exhibit was material from

Donald Boozer’s 2008 exhibit, "Esperanto, Elvish, and Beyond: The World of

Constructed Languages" at the Cleveland Public Library. The exhibit includes a history of

conlanging, and many samples of conlanging in science fiction and from the

conlang community. Boozer created A Conlanger's Bookshelf: Books, Movies,

Television, Games & Web Resources for the Beginning to Advanced Conlanger

as a companion to the exhibit.

Some of David J.

Peterson’s extensive conlang work–books, games, many languages,

orthographies, and scripts–were shown. An early work in Megdevi combines

drawings and language in a fairytale format.

Jim Rosenberg,

an artist of hypertextual, interactive, electronic poetry, attended the meeting

and suggested that the time had come for a conlang literature. Such an

anthology is now under discussion on the list.

Fiat Lingua!

I find myself

developing my own meta-myth about conlangers as language-bringers. In the

spirit of play, in the rigor of serious linguistic exploration, in the

willingness to live in one’s own highest myth for extended periods of time, for

explicitly not putting

aside childish things, I think we are one of the points where the incursion of

novelty in the run-up to 2012 reveals itself–in this case in a geyser of

glyphs, a flow of new sounds, and newly ordered ways of making meaning.

A version of

this article with more pictures can be found at Diana Slattery’s Xenolinguistics blog. Many

conlangers maintain extensive websites for further reference.