An interview with Charles Shaw, author of Exile Nation, which appeared in serialization on Reality Sandwich and was recently published by Soft Skull Press.

Mark Heley: I’ve seen a number of reviewers describe your book Exile Nation as a ‘gritty prison memoir’, but it feels to me more like a ‘coming out’ book. You certainly deal with your time in prison in a vivid manner, but what I think is more unique about the book is that you are bringing your story to a place of redemption by standing by your use of substances like MDMA and psychedelics as tools for personal growth.

Charles Shaw: Yes, I think it was a coming out on multiple levels. At its core, it was me kind of coming out to myself with the truth of my life and my experiences. For me to actually get through all of this, to find a way to live with all of it, I had to embrace it completely. I had not only to own everything I had done, but also to deeply reflect on it and reflect on all of the reasons why and then connect them to all of the relevant social issues. One of those issues was the way that our society treats drug addicts and people who run into these huge problems. Society doesn’t really provide anyway to get better, the only thing that is available to people are twelve-step programs that have a limited applicability and success. In fact, they have an abysmal rate of success, to be perfectly honest. I think that the official stats are something like 90% of all people that enter treatment ending up using again within five years.

So, knowing all of this and knowing that I had nothing to lose and knowing that I found these tangible and real benefits from MDMA, LSD and DMT and all the other psychedelic medicines, it felt like the whole story served that issue. To bring all of this to the forefront to attempt to shake up and change whatever dialogue exists about these topics. I think one of the reasons that I’ve had some success in doing that is that I’m one of the few people that have gone through that world and have come back out bringing something back with the intention of changing the dialogue.

How would you describe the way that you would like to see the dialogue change?

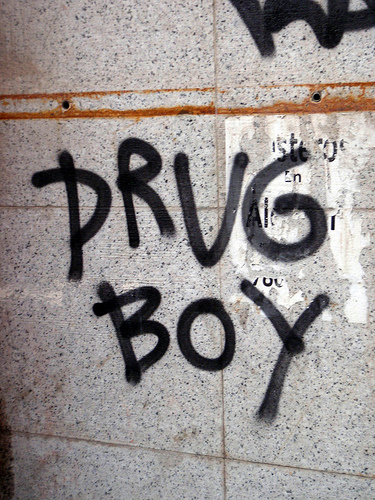

From my personal perspective: crackhead, drug addict, convict, offender,. …these are all, if you’ll pardon the expression, variations on the term ‘nigger’, in some way, or the other. What these terms serve is the exact same purpose that that word served in previous generations and in some ways because of the impact that it has had on the African-American community, in particular, it’s been a kind of ‘bait and switch’ in terms of terminology. However, it also represents that class of society that is essentially exiled from the fruits of society, from the ability to participate and to prosper. It all comes down, in the Marxist analysis that Noam Chomsky and Christian Parenti offer, to the idea of surplus population, of surplus labor. It’s the idea of this permanent underclass that needs to be managed. There are whole functional, industrial, economic aspects to that, that we see in the correctional system,

On a more sociological level, there needs to be this despised underclass. This underclass allows the people that perceive themselves to be above them to feel better about the way in which their lives are screwed over, because at least there are not ‘those people down there’. It’s this kind of stigma that has created a block in our ability to discuss things because we still apply this very moral criterion to judge these people who have a very understandable illness, whether they are not they are acting out a PSTD disorder, or have run-of-the-mill addictions that they have inherited from their families.

Yes, today we have a greater compassion for addiction, but still when it comes down it, when someone like Whitney Houston, or Amy Winehouse dies because of their addictions; they are just brutally raked over the coals by a society that doesn’t care. A society that says that they deserved it and that they brought that on themselves (because of their addictions) and that we shouldn’t have any compassion, because they were rich and successful, or whatever.

I guess when people can look at Whitney Houston, or Amy Winehouse, and someone living in the street as both suffering the same level of pain and alienation and anxiety and sickness. Then I think we’re getting somewhere. I wanted to flip all the notions that we have, mainly by putting myself out there and saying that society named me a ‘crackhead’ and unredeemable. And yet, I was able to fight through it and if I can fight through it, then other people must be able to fight through it and there must be something else going on rather than just me being morally deficient, or genetically ill, or waste.

Exile Nation is a story of drugs and redemption. Most stories of drugs and redemption go from drugs to no drugs, but you going from one type of drugs, to another type of drugs. What I really felt was interesting about your voice in the book is that you do so with a great deal of honesty and without apology and that’s quite a unique perspective. Do you think that’s accurate?

Definitely. We have a monolithic understanding of our drug culture. Just the fact that the word ‘drug’ is used, you know, immediately pigeonholes it into a very narrow category. This idea that one is trading one set of drugs for another… the clinical term that people love to use is ‘transferring addiction’…belies the fundamental misperception and misunderstanding of what is actually going on. On the first level, you have to separate consciousness-expanding drugs, or substances, or compounds, from those that anathesetize or ‘narcoticize’, as they say. There is one psycho-spiritual phenomenon going on when one self-medicates to tamp down on pain, or anxiety, and there’s an entirely different phenomenon going on, when a person is exploring the realm their consciousness, or the boundaries of their consciousness in order to experience enlightenment, awareness, or in my case, healing.

If we can shift that debate, primarily into the therapeutic paradigm, as organizations like MAPS are doing, where they are talking about legitimate therapeutic applications with grounded science and a maturing culture, then we will have achieved something. It takes all of the writers, who are doing this work currently, to really take it into this intellectual discussion and to say yes, this is not just reckless behaviour; this is actually extremely responsible behaviour, although it requires a lot of risk-taking. It takes commitment to go into those realms and really face what you find there and to come back out with something that is a benefit to you and hopefully others.

It seems to me that the whole issue of the ‘War on Drugs’ is the elephant of the room in the US right now. It’s interesting that your individual journey has taken you to a position where you can actually say that very publicly. There are still a lot of people that are living in fear of the consequences of stepping forward and saying, ‘Yes, I’m someone who thinks that certain consciousness-expanding drugs- in your choice of words- have merit and don’t make me a lesser human being’.

What I think is really interesting is Jonathan Talat Philip’s recent Huffington Post piece where he highlighted my book and several others as representative of the new spiritual counterculture, or what he called the ‘new edge’. He’s presenting this pairing of tragic and traumatic life experiences such as Daniel Pinchbeck’s alienation in ‘Breaking Open The Head’, or the separation that I experienced in my book and then coming back to some spiritual, or shamanic, medicine to integrate. However, in the comments section, somebody comes back and says. ‘Oh well, this may be great, but if we really have to go back to the days when people are using drugs to expand their consciousness, then we haven’t really progressed at all’.

There’s so much that is wrong about that statement, I don’t really know where to begin. The first and foremost point probably being the idea that Professor Ronald Siegel at UCLA, a former government drug expert and now someone who has studied addiction and the use of intoxicants probably in greater detail than anyone else I could cite at the moment, has put forward. His book, ‘Intoxication: the universal drive for mind-altering substances’, states very clearly that our use of consciousness-altering substances and our desire to transcend our (ordinary) states of consciousness and to be intoxicated, is a what he calls our ‘fourth primal drive’. It’s something that we have done ever since we have been able to make sense of anything, for thousands and thousands of years and we’ve done this by watching the animal kingdom and then by going and mimicking it. Therefore, we watch monkeys get drunk and reindeers eat mushrooms, so on, and so forth. We’ve repeated, replicated, and modelled this behaviour and refined it down, until today, where there is ‘a pill for every ill’. Yet, at the same time, we remain in a bizarre, twisted paradigm of denial and delusion, where if a pharmaceutical company sanction the use of a compound, that’s ok, but if the same compound is on the street, then that’s not. It’s completely schizophrenic. The first thing we have to do is to admit that all of us do this in some way, or another.

All the justifications (for the current paradigm) are either sociological, or political, in some way or another. None of them are really grounded in any tangible science, or in any clear, or present danger. Yes, of course, prohibition creates violence and black markets, but these are problems of prohibition. Drug use and the problems of drug use are always there, in one way, or another. Because that’s our nature.

In the book, you talk a lot about your activist history and it seems as if you are now emerging as a new kind of activist. Do you think your work is now moving from organization to inspiration? Do think of yourself as a different kind of activist now?

I would like to think so. One of the core struggles in the book, particularly in a number of chapters that didn’t make it into the book, but are still available to read on Reality Sandwich, charts my journey into the old paradigm of populist, or street activism, or direct action. I had to find out the hard way that really doesn’t work anymore, that it’s an ineffective paradigm that allows itself to be easily marginalized, easily controlled and easily defused, separated and ultimately dismantled.

There’s a passage in the book where I have my first experience with DMT. One of the visions and journeys that I go on is this trip through the old paradigm in the sixties and the seventies, where I watch the movement rise up and then I watch it destroyed by the idea of being divided against oneself. Daniel Pinchbeck calls it ‘oppositional dynamic’. I just call it divide and rule. It’s one, empirically the same, group that is set against itself with only minor ideological and moral differences. It’s a tool that has been used forever. If you understand that this has been a tool of imperial expansion and control, the first thing you have to do is to come from a place of unification. I think that people can unify when they see affinity with each other and the way that they see affinity with each other is through a common story. A number of years ago, in the middle of the last decade, there was a lot of literature being put out by authors like George Lakoff that talked about reframing the political debate and changing the stories of our culture. I took that very seriously as a way of helping people shift their perspective about how they go about creating social change, So despite all that’s been invested in the Occupy movement, maybe that’s really not the best way to go. Maybe going into the street and fighting with the police isn’t the best way to get the point across. In fact, maybe that’s actually serving the problem. As Bucky Fuller said: ‘You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.’

On some level, this transformational, consciousness, or festival culture- whatever you want to call it- is one of the biggest outside attempts to change that paradigm. Instead of creating a movement to destroy something, it’s a movement creating something and something that is a greater reflection of where we all want to be.

Mark Heley: How do you see with your work with the Exile Nation project fitting with your involvement with projects like the Fractal Nation village at Burning Man?

Charles Shaw: I think that the unspoken connection is that there are so many people in this world that have intersected with our morality laws. Particularly, in the form of drug laws. You’ve got people who are living in a visionary culture where substances are an integral part of the consciousness, but you’ve also got very unorthodox social situations, including sexual and romantic relations. Some people see it as cutting edge; others see it as licentious, or decadent. Anyway you look at it, it’s not held by a lot of comfort, or understanding, by mainstream society and so, it has to exist in this bubble. There are all these philosophical theories that it only takes 10% or so of the cutting edge of a culture to affect the direction of the whole culture. I’d like to think that entities like Fractal Nation, or The Do Lab, or any group that is trying to create new models of art, sustainability, or community, that they are this cutting edge. If I’m trying to inject cutting edge thinking about our social constructs into this visionary culture that is primarily driven by the aesthetic, I think that helps build a stronger foundation and it keeps people politically aware. People for forty some years have gotten used to living underground with psychedelics, in particular, and forming all of these subcultures…the dead-heads and the phish-heads and so on. I just don’t think that it’s time to hide in a subculture anymore. I think it’s time to start really integrating these lessons into a larger context. Therefore, for me, the way that is done is to put it within the context of politics and policy, but also in the terms of healing and feeding a greater spiritual need.

Photo by Daquelle manera, courtesty of Creative Commons licensing.