Razzle, dazzle, drazzle, drone, time for this one to come home?

Razzle, dazzle, drazzle, die, time for this one to come alive?

And hold my life until I’m ready to use it?

Hold my life because I just might lose it

Because I just might lose it

–from Paul Westerberg’s Hold My Life

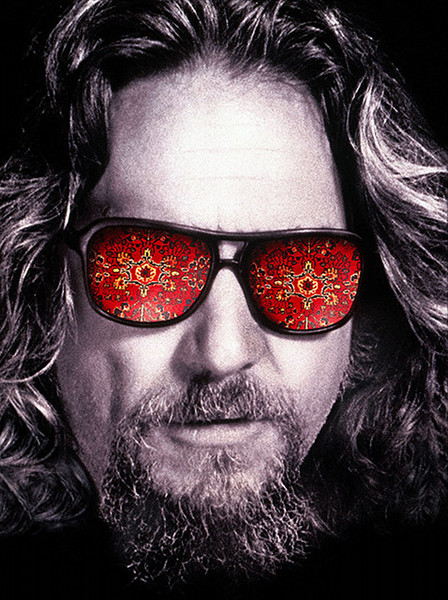

An essay I’ve recently published in Reality Sandwich, “An Esoteric Take on The Big Lebowski,” has been very well received. There are a few works out there, be they novels, movies or even pieces of music, that manage to make the esoteric, exoteric. Such works rarely surface, though, because the shallow machinery of the publishing, movie and music industry is mostly allergic to them. As I was re-reading Lin Yutang’s masterwork, The Importance of Living, I found so many passages that seem custom-made for the Dude that I thought it might be fun to explore the points of departure and arrival of both works, in tandem. To do that, I need to start from the not-so-distant premises that prompted Lin Yutang himself, back in 1937, to write his book.

Even today, despite the West having gone through an unprecedented process of secularization, the numbers are staggering: there are 2.1 billion Christians worldwide; 1.6 billion Muslims; about 900 million Hinduists; and 350 million Buddhists. Therefore, almost 5 billion people follow the four largest religions, which have one common trait — they are life-renouncing.

In a nutshell, the Abrahamic religions — Judaism, Christianity, Islam — see life as a period of probation in which man, by acting virtuously according to the doctrine set out by each religion, will earn for himself a place in heaven. The focus, therefore, is on the afterlife. Life on earth is a series of tests that must be passed and temptations that must be resisted. Again in a nutshell, Hinduism and Buddhism, the two major Indian religions, are similar in that both hold that life is suffering and the only way out is freedom from the endless chain of reincarnations. The ultimate goal of life, referred to as moksha and nirvana respectively, consists of liberating oneself from samsara, thus ending the cycle of rebirth. Union with God can then be attained.

Recently an old friend of mine, for years a convert to Buddhism, suffered an aortic dissection, a life-threatening tear in the aorta that I am familiar with because my father died of it. When he began to feel sick a friend who was with him, a medical doctor, rushed him to a hospital, where he was operated on within minutes. For days his life hanged by a thread in the ICU. His anguished wife, back at home, organized reunions with fellow Buddhists who would pray and chant together for him to be spared and then recover. As I followed from a continent away, my heart went out to him and his family and friends, but in the back of mind I couldn’t stop hearing a nagging voice. It asked: “What business do Buddhists have in asking to prolong one’s life?” It was incongruous. The followers of the most life-renouncing religion known to mankind were fervently praying for this one man to cling to life. Mercifully, the surgery was successful and my friend pulled through, but I still wonder if his Buddhist wife and friends behaved consistently with Buddhism?

Of course they didn’t, and this incident is meant to make a point: almost five billion people living on this drinkable, edible, and breathable planet of ours follow religions that, I fear, go against our nature. Normally, we want to live, not to let go of life. It is only natural, so natural, in fact, that it seems very strange that this would need to be stated in the first place.

Lin Yutang’s world was less populous than ours, but in proportion more religious yet, especially in the West. Back in his day some pioneers were exploring the “occult”, that more than vague definition that has been since subdivided into many fields: the Royal Art, Alchemy, parapsychology, extrasensory perception, dream interpretation, lucid dreaming, out-of-body and near-death experiences, not to mention humanity’s penchant for the most varied psychoactive substances in the hope that altered states will lead in the exploration of parallel or otherworldly realities. From all this and the four major life-renouncing religions I’m bound to infer that by and large we don’t like our lot on earth. Lin Yutang started from the same premise.

Like early man, do we envy the birds for being able to fly? The fish for being able to breathe under water? Cats for seeing in semidarkness? The list goes on and on: from a physical standpoint, we’re inferior to so many species. But not to worry, modern man has come up with a number of flying contraptions, scuba diving equipment, night vision goggles, and many other gadgets that mimic the abilities of more physically gifted species. And yet the premise stands: either our adherence to a life-renouncing religion, or, more recently on a large scale, our multifarious attempts at transcending our very nature and condition.

That we feel distinctly uncomfortable in our own skin is not a supposition but a statement of fact. Do we feel so chokingly uncomfortable because the first time we realize that, sooner or later, we are doomed to die, our natural impulse is to cry? My wife and I have witnessed this reaction in two of our three boys. When, around five years of age, they understood that life doesn’t last forever, they cried inconsolably, out of disbelief, then anger, finally fear. This tragic cognizance we carry inside ourselves for our whole life. It’s our congenital memento mori, which kicks in the moment the concept of time ceases to be a present-tense continuum, as it is during early childhood, and becomes one of duration, with a precise beginning and end.

For the materialists, those not interested in religions or attempts at transcending human nature, there are the following bits of ancient wisdom: Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s “Live each day as if it were your last;” the ancient Roman poet Horace’s Carpe diem, seize the day, which was reprised during the Renaissance by Lorenzo De’ Medici in his famous poem Canzona di Bacco, Bacchus Song, which begins: “Youth is sweet and well / But does speed away! / Let who will be gay, / Tomorrow, no one can tell;” even the ancient Chinese proverb: “Enjoy yourself; it’s later than you think.” Many agnostics, atheists, and skeptics have no better guideline than this to live by, and accordingly try to feast on life, which, they perceive, is “here today, gone tomorrow.”

Lin Yutang offers an approach that goes beyond life-renouncing religions, daring transcendental explorations, and clichés such as enjoy yourself, it’s later than you think. One thing was clear to him as it must be to so many of us: being alive, living, matters. The Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke suggests why in the ninth of his Duino Elegies, written between 1912 and 1922, and excerpted here in the translation of A. Poulin, Jr. To the question, “Why, then, do we have to be human and, avoiding fate, long for fate?” the poet replies: “Because being here means so much, and because all / that’s here, vanishing so quickly, seems to need us / and strangely concerns us.” And a few lines down: “To have been on earth just once — that’s irrevocable.”

How are we to celebrate, then, the plain yet miraculous reality of being alive? The poet surprises with “Praise the world to the angel, not what can’t be talked about. / You can’t impress him with your grand emotions. In the cosmos / where he so intensely feels, you’re just a novice. So show / him some simple thing shaped for generation after generation / until it lives in our hands and in our eyes, and it’s ours. Tell him about things. He’ll stand amazed (…)”

So there it is, straight from the pen of one of the most mystical poets in western literature: an exhortation to speak to the angel not about grand emotions but about the world, about things. Some years after Rilke finished his elegies, Lin Yutang wrote in The Importance of Living: “As for philosophy, which is the exercise of the spirit par excellence, the danger is even greater that we lose the feeling of life itself. I can understand that such mental delights include the solution of a long mathematical equation, or the perception of a grand order in the universe. This perception of order is probably the purest of all our mental pleasures and yet I would exchange it for a well prepared meal.” Years ago, when I first read this passage, I laughed out loud. It was liberating. But where is Lin Yutang coming from? In another book of his, The Wisdom of China, he remarks: “The Chinese philosopher is like a swimmer who dives but must soon come up to the surface again; the Western philosopher is like a swimmer who dives into the water and is proud that he never comes up to the surface again.”

I’d tend to agree, but there probably is a linguistic reason for this. The Chinese never developed a proper alphabet, but rather ideograms, or Sinograms, or better yet, Han characters. The Kangxi Dictionary contains the astonishing number of 47,035 characters. Compared to the 24 letters of the Greek alphabet, the 23 of Classical Latin and the 30 of the German alphabet, it’s evident that writing and reading in Mandarin is an effort in itself, which explains the emphasis placed by Chinese on calligraphy.

Ancient Greek, Latin and German have been used by most of the greatest philosophers of the western tradition, with Latin being the lingua franca of European scholars for centuries. Inevitably, intellectuals would be tempted to play around with words — and they did! Western philosophy is immensely more voluminous than its Chinese counterpart, but its value should always have been considered from an historical perspective. No one in his right mind should have argued over, say, St. Thomas Aquinas’s five proofs of the existence of God — but that went on for centuries. The history of Western (theoretical/discursive) philosophy ought to have been read like the history of architecture: philosopher so-and-so built that castle in the air, while his opponent built this other castle. Western philosophy should be appreciated aesthetically rather than intrinsically.

Again in The Wisdom of China, Lin Yutang writes: “The Chinese can ask . . ., ‘Does the West have a philosophy?’ The answer is also clearly ‘No.’ . . . The Western man has tons of philosophy written by French, German, English, and American professors, but still he hasn’t got a philosophy when he wants it. In fact, he seldom wants it. There are professors of philosophy, but there are no philosophers.”

So, what exactly does Lin Yutang prescribe as a philosophy of life? And how does the Dude, our hero (I haven’t forgotten him), happen to behave in accordance with so many of the philosopher’s ideas?

A good point of departure is the stubborn persistence, even in our secularized western world, of Manichaeism. In short, Manichaeism is a dualistic religious system of the prophet Mani (c. 216-276 AD), a mix of Gnostic Christianity, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and other elements, whose basic doctrine is an unrenounceable conflict between light and dark, with matter being regarded as dark and evil, and the spiritual world as light and benign. Denis de Rougemont has written a seminal book, Love in the Western World (1939, revised 1972), in which he argues in my view convincingly that in the West there exists a single love story, that of the Tristan myth of the star-crossed lovers who cannot find love on earth but only in the afterlife. It is a purely Manichean theme that, incredibly, haunts us to this day. For example, the most popular love story ever filmed, Titanic, is a pure reenactment of the Manichean Tristan myth. It says explicitly that perfect love cannot be had in the world of matter, but only in the world of spirit. Tens of millions in the West believe this, whether or not they’re aware of it.

In The Importance of Living, on the other hand, Lin Yutang entitles the sixth chapter The Feast of Life. It begins with some assertions that go very much against the grain: “Philosophers who start out to solve the problem of the purpose of life beg the question by assuming that life must have a purpose. (…) I think we assume too much design and purpose altogether. (…) Had there been a purpose or design in life, it should have not been so puzzling and vague and difficult to find out.” Later on, in a brilliant twist, he adds: “Are we going to strive and endeavor in heaven, as I am quite sure the believers in progress and endeavor must assume? But how can we strive and make progress when we are already perfect? Or are we going merely to loaf and do nothing and not worry? In that case, would it not be better for us to learn to loaf while on earth as a preparation for our eternal life?” I can see the Dude smiling here. Human happiness, Lin Yutang continues, is “largely a matter of digestion. (…) if one’s bowels move, one is happy, and if they don’t move, one is unhappy. That is all there is to it.” Take that, transcendentalists! If this sounds like a crass remark that may come out of Sancho Panza, it is not, and we shall see why.

Human happiness is sensuous, and there need not be a polarity between sensual and spiritual pleasure. Manichaeism, in other words, is really a bad habit. “My suspicion is, the reason why we shut our eyes willfully to this gorgeous world, vibrating with its own sensuality, is that the spiritualists have made us plain scared of it. A nobler type of philosophy should reestablish our confidence in this fine receptive organ of ours, which we call the body, and drive away first the contempt and then the fear of our senses.”

In The Big Lebowski the Dude is rudely extrapolated from his habitual milieu and insulted, threatened, and beaten repeatedly. But in the brief interludes in which he’s left in peace, we see him smoke weed; take a warm bath while enjoying the songs of the whales; lie on his carpet while listening to bowling sounds; sip his beloved White Russians; engage in Tai chi, and so on. All sensual pleasures that add to his spiritual enjoyment of life, too. “Only by placing living above thinking can we get away from this heat and the re-breathed air of philosophy and recapture some of the freshness and naturalness of the true insight of the child.” Materialism should never be that of Sancho Panza, nor spiritual yearnings should negate our sensual enjoinment of life. According to Confucianists, the highest conception of human dignity is “when man reaches ultimately his greatest height, an equal of heaven and earth, by living in accordance to nature.” In The Golden Mean the grandson of Confucius writes: “What is God-given is called nature; to follow nature is called Tao (the Way); to cultivate the way is called culture. (…) When a man has achieved the inner self and harmony, the heaven and earth are orderly and the myriad things are nourished and grow thereby.”

The following chapter in the book seems, again, custom-made for the Dude. In the opening of The Big Lebowski, the cowboy narrator says as a voice-over: “… And even if he’s a lazy man, and the Dude was certainly that — quite possibly the laziest in Los Angeles County… which would place him high in the runnin’ for laziest worldwide –(…)”. Yes, the Dude is far from full of zip, and Lin Yutang chimes in with another perfect chapter for him: The Importance of Loafing. Eventually we stumble on the following marvelous challenge to our assumptions, or rather the assumptions imposed on us by canonical western culture: “Time is useful because it is not being used.” Forget “time is money”! And there’s more. “On the whole, the enjoyment of leisure is something which decidedly costs less than the enjoyment of luxury. All it requires is an artistic temperament which is bent on seeking a perfectly useless afternoon spent in a perfectly useless manner. The idle life really costs so very little.” We can think of countless afternoons the Dude must have spent bowling or enjoying any of the other activities (?) he is keen on. The art of living should never degenerate into the mere business of living, and the Dude is a consummate artist. What if this earth were our only heaven? The Dude tries to make the best of it, but without hedonistic excesses. In fact, even under duress, he consistently comes off as balanced and level-headed.

And it is here that Lin Yutang finds it appropriate to explain that “the distinction between Buddhism and Taoism is this: the goal of the Buddhist is that he shall not want anything, while the goal of the Taoist is that he shall not be wanted at all.” And that’s exactly how the Dude was living until some thugs, because of a case of mistaken identity, did want him, and all his troubles began. Up to then, we assume, he was being a perfect Taoist, and a Taoist he tries to remain even through all the vicissitudes he didn’t ask for.

Chapter Nine, The Enjoyment of Living, is yet another Dudeist delight: it begins with On Lying in Bed. “It is amazing how few people are conscious of the importance of the art of lying in bed.” Lin Yutang goes on to describe in detail how many benefits can be found in this very natural non-activity, and I can’t imagine the Dude disagreeing in the least. “It is amazing how few people are aware of the value of solitude and contemplation. The art of lying in bed means more than physical rest for you (…). It is all that, I admit. But there is something more. If properly cultivated, it should mean a mental house-cleaning.”

When the Big Lebowski rudely asks, “Are you employed, sir?” the Dude is dumbfounded. “Employed?” he retorts. From the depths of his Taoist core, this must sound like the question from a being with a very low level of consciousness. Doesn’t the Big Lebowski know, the Dude could be asking, that, for example, “a writer could get more ideas for his articles or his novel in this posture (i.e., lying in bed) than he could by sitting doggedly before his desk morning and afternoon”?

Other subchapters would delight the Dude: On Smoke and Incense; On Drink and Wine Games; The Inhumanity of Western Dress (the Dude certainly favors comfort over restrictive, choking garments).

The chapter The Enjoyment of Travel further enlightens us. When traveling in a strange land, as a Chinese nun put it, “not to care for anybody in particular is to care for mankind in general.” Lin Yutang elaborates with one more startling concept: “There is a different kind of travel, travel to see nothing and to see nobody, but the squirrels and muskrats and woodchucks and clouds and trees.” We do focus on human beings too much, don’t we? “To be able to float about is already a special talent.” And the Dude sure can float. “And to be able to wander about at ease is already to have a special vision.” And in the film the Dude sure wanders from place to place, from hostile to hostile, always at ease despite the rude receptions.

We get the impression that the Dude is under so much pressure that he’s forced to drink more White Russians than usual and smoke more weed, too. He tells Maude, after he’s unwittingly “helped her to conceive”: “Fortunately I’ve been adhering to a pretty strict, uh, drug regimen to keep my mind, you know, limber.” Yes, it must have been very unpleasant to be insulted, threatened and beaten by so many people in such a short period of time. Normally the Dude probably wouldn’t need such a “pretty strict drug regimen” because, as T’u Lung writes in The Travels of Minglaiotse (translated and excerpted in The Importance of Living by Lin Yutang) “The art of attaining happiness consists in keeping your pleasures mild.”

Finally, we come to the subchapter Art as Play and Personality. We know the Dude is an avid bowler, so clearly playing is very important to him. “Now is characteristic of play that one plays without reason and there must be no reason for it. Play is its own good reason.”

The book closes with a final exhortation to be reasonable. And the Dude certainly proves vary reasonable before the very unreasonable events that befall him, as well as the very unreasonable temperament of his foil, his buddy Walter.

In the end he’s shown smiling, “taking it easy for all of us sinners” and, in essence, abiding. Indeed, “The Dude abides.” Much has been made about this closing statement, and much should have been made of it. But over the course of the film the Dude is shown under duress, not in his normal life. He does a terrific job in remaining balanced, level-headed and reasonable; he does abide, and how. But there is implicitly much more to the Dude. Too much of his lifestyle-the glimpses we catch of it amidst the turmoil-seems to be directly inspired by Taoism. Most of all, this: his having achieved transcendence within the limited sphere of his human immanence. Precisely in this lies the secret of life intended as heaven on earth.

Look, I’m alive. On what? Neither childhood nor

the future grows less… More being than I’ll ever

need springs up in my heart.

–From Rainer Maria Rilke’s Ninth Elegy, translated by A. Poulin, Jr.

Image by Sleeper Cell, courtesy of Creative Commons license.