Mmmmm. Smell that smell. So much death – so little closure! Post-9/11 popular culture is teeming with zombies. A veritable epidemic – it seems the kids can’t get enough of the partially albino skin and the hollow, soulless, CGI eyes.

Examples abound, starting with three Resident Evil movie blockbusters based on the thirteen (!) video games that make up the series with the same name. There was also a remake of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (2004), and one of I Am Legend (2007). The British film 28 Days Later (2002) was a commercial and critical hit. It inspired a graphic novel, 28 Days Later: The Aftermath, and a film sequel, 28 Weeks Later (2007). The sub-genre is such that it garnered its own zombie parody: Shaun of the Dead (2004). Otto, or Up with Dead People (2008) by Canadian director Bruce La Bruce is calling itself the first gay zombie movie. And there’s already been a queer zombie musical – Z-Spot: A Zombie Musical (specifically, lesbian catholic schoolgirl zombies) was featured at Burning Man in 2006. There have been zombie protests, zombie walks/crawls in San Francisco, Toronto and New York at which people are encouraged to meet at a certain time and place to hit the streets made up as zombies, looking for victims who show that they are participating by wearing a predetermined sign like a piece of duct tape placed visibly on them, so that the undead know to pounce on them, usually several at a time, and tear at their clothes, put makeup on them and turn them into one of them. In some cases a substance described as “purple goo” is used. Apparently Apple stores are a favorite target as the Genius Bar is said to be full of tasty brains.

While interest in the undead predates our cultural moment, I think that the reason for the current trend is twofold; as a metaphor, a zombie apocalypse resonates strongly with many of our repressed fears and notions in the wake of September 11th. As an experience, acting out a zombie apocalypse is a way of participating in the kind of viral “outbreak” that mirrors the proliferation of the internets through which many of us live our lives. The post-9-11 generation, by which I mean anyone who identifies as “young” and spends a meaningful portion of their lives online, uses zombies as a rallying point from which to stage blog and text-messaged communicated events, public “theater of cruelty”-type explorations (we fake it so real we are beyond fake, to paraphrase Courtney Love) of our oscillations between the mindless group think of the mob and the terrifying isolation of the individual.

The zombie trend is a celebration of fear – a way to paradoxically act out the suffocating effect that the blanket of information noise has in our Westernized, late capitalist existence. When you’re dead there aren’t any more expectations – there aren’t any more goals, just endless in-between time spent hanging out and eating. While online one just “sits there,” doing nothing. There’s definitely a punk rock aspect to zombies–an anarchistic refusal to work or follow rules. As a look it goes well with Converse sneakers and skinny jeans. It’s liberating to be the deceased version of yourself – the you that you’ll never know. There’s an action shot on Flickr of an office type wearing a jacket and tie and preppy, wire rimmed glasses with excellently applied fake blood smeared across his face and a vacant look in his eye… I could see myself having fun doing something like that.

Zombies represent the fear of being devoured by the Other–of being consumed or subsumed by an enemy who secretly lives among us and shares aspects of our appearance but is drastically and grotesquely inhuman in a way that curtails any possible communication. The Other among us could be homegrown cells of Islamic terrorists, or The Other could mean the other side of the red state/blue state division. For some, the Other is a woman, for someone else, the Other is black… or white.

The other could be those of the customer service class created in order to maintain the many comforts of the middle class; the fact that nearly all contemporary zombies are depicted as bloodthirsty cannibals attests to the late capitalist fear of being devoured by our own appetites.

The zombies also represent the fear of being turned into mindless slaves by our own technology à la The Matrix, as we move into an age of linked-together knowledge systems that makes us nodes on our own network. I Am Legend, 28 Days Later and its sequel, 28 Weeks Later are about global epidemics that are the result of a scientific cure or experiment gone wrong. The rising up of the dead, as promised in the Bible, happens as both signal and cause of the end of days. Perhaps our need to depict massive numbers of living dead people is a way of speaking to ourselves, humankind to humankind, so that we can tell ourselves things we otherwise couldn’t put into words. The desire for a greater sense of oneness and more meaningful connections with others goes hand in hand with the fear of losing one’s individuality. In each of these movies, there is a constant, sliding scale between the terror of “last man on earth”-level isolation and the insane babbling of becoming a rabid, soulless monster. We see what is at the core of all human communities – the need for protection and for executing plans by working as a team.

As beings which have come back from the dead, from being hidden, zombies are the return of what Freud refers to in his essay, “The Uncanny” as “long surmounted thoughts.” These are thoughts about death and dying that we’re taught to regard as “primitive” or “religious.” The modern world keeps death practical and solemn. Yet, as Freud mentions, it’s rare to find someone who isn’t susceptible to some form of superstition, especially when actual events seem to support the theory. For example, in conversations with others one occasionally admits to a belief that America as a country is haunted and/or cursed, and that the failed war and failed economy are payback from all the evil we’ve inflicted upon the world. An overwhelming sense of guilt is transmitting gusts of guilt like Van Gogh swirls across the sky. The zombies are the thousands of 9/11 victims, slain soldiers, Iraqi civilians and expired rescue workers over whose deaths we feel a guilt that we’ve worked to expunge from our daily consciousnesses. The fact that very few bodies have been recovered from the WTC site or that we are not allowed to see pictures of flag-draped coffins means that death is something hidden, which means we don’t have to deal with it. The zombies are the grisly reality of that death.

The strange sensation that comes over us when actual events seem to confirm old, discarded beliefs is that of the uncanny. It’s usually something that happens in fiction, but 9/11 was an example of the uncanny occurring in real life. On 9/11, the attack on the Twin Towers was at once incomprehensible and very familiar. We’ve all seen New York City destroyed, time and time again, in one disaster movie after another. On 9/11 the most familiar city skyline in the world was rendered forever unrecognizable in a single hour. On 9/11 the supposedly impenetrable fortress of the world’s mightiest war machine was itself attacked and partially destroyed. In his essay, Freud examines just what it is that creates this sensation and focuses in on the actual word – uncanny – in German, unheimlichkeit. “Heimlich” means “home” and “familiar” and so the “unheimlich” is that which is “unfamiliar”–but still of the home…it is not the opposite, as such, but a transformation, as though the home has become haunted.

Freud writes:

"Thus heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich."

Ambivalence goes hand in hand with the uncanny; Freud says elsewhere that the uncanny is where we don’t know where we’re going. There is an uncanniness to a moving, walking corpse that seems, in the very act of becoming reanimated, to lose all notions of humanity. As “night seekers,” the zombies leave their daytime cities at an eerie, abandoned standstill. Perhaps some of strongest sensations of uncanniness come from the scenes of deserted London or New York. Borrowing from Last Man on Earth, the Post 9-11 have moments of harrowing isolation, in which Cillian Murphy’s character Jim, in 28 Days Later screams “Hello” at a blankly silent London until he is nearly hoarse. The London Eye Millennium Wheel rising up on the horizon is at once absurd and tragic in the absence of a citizenry. The familiar sights taken in the foreign context of being without people creates an undeniably uncanny effect. In I Am Legend, Will Smith’s character, Robert Neville, is unraveling from the mental strain of being ostensibly the last man on earth. In a fit of paranoid panic we watch as he shoots out the top windows of darkened skyscrapers, as if someone was up there, watching him.

Freud explains that another cause of the uncanny is the confusion or inability to tell whether something is human or not. For instance, a young girl who turns out to be a doll creates an uncanny effect in the E.T.A. Hoffmann story, “The Sandman.” This effect is especially uncanny when it comes about over confusion whether someone is alive or dead. In each of these movies it is necessary for the human survivors to think of the zombies as inhuman in order to kill them with impunity. The undead are referred to as “those things” and “the infected.” In contrast to this, all that is human about the last survivors is brought to light, including the torment of their isolation. In cases where there are more than one survivor, the mini-community they form represents a kind of utopia, as the audience is able to relax for a few moments in the oasis of familiar domestic warmth that the survivors create. Class and racial distinctions are seemingly done away with, as the survivors form the basis for a new society. That which is Heimlich, or homely, becomes more pronounced against a back drop of inhumanity.

In each movie, nearly human things take on human qualities. Robert Neville keeps up a fake banter with the mannequins in a deserted video store that he comes to every day to return the night’s previous DVD as he slowly works his way alphabetically through the titles. He’s named the various mannequins in the store and carries on a friendly banter with them. Their silence, which is part of the overall silence that clings to every part of the once noise New York City, adds to the uncanniness, In 28 Days Later the rage virus makes its initial jump from chimpanzee to human when a group of animal activists risk their own lives to free the animals. We see one chimp bolted down to a table and forced to stare up at several monitors playing different footage of violent mob scenes, riots and armies of police beating crowds. It is some kind of bizarre experiment, the structure and goal of which is unclear. The soon-to-be-human carrier gazes upon this poor creature as though she is gazing upon a fellow human. As the activists open the cages to set free the monkeys, a laboratory scientist pleads that they stop, or else they’ll release the experimental rage virus. The activists ignore him – the inhumanity of his endeavors has rendered him untrustworthy.

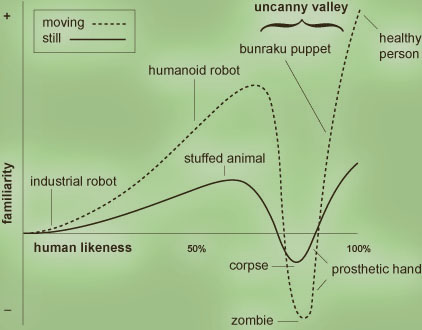

Not surprisingly, zombies rate at the bottom of the curve, deep in the heart of the uncanny valley. The Uncanny Valley is a theory proposed by computer scientist Masahiro Mori which attempts to describe the effect whereby a robot that looks nearly human is more likely to elicit a negative reaction in an observer than one that is obviously not trying to look too lifelike. From Wikipedia:

"Mori's hypothesis states that as a robot is made more humanlike in its appearance and motion, the emotional response from a human being to the robot will become increasingly positive and empathic, until a point is reached beyond which the response quickly becomes that of strong repulsion. However, as the appearance and motion continue to become less distinguishable from a human being, the emotional response becomes positive once more and approaches human-to-human empathy levels."

This area of repulsive response aroused by a robot with appearance and motion between a "barely-human" and "fully human" entity is called the uncanny valley. The name captures the idea that a robot which is "almost human" will seem overly "strange" to a human being and thus will fail to evoke the empathetic response required for productive human-robot interaction.

A zombie elicits the strongest negative response precisely because it is almost human in appearance – more lifelike than a stuffed animal – which is what makes its radical inhumanity so alarming. Stilted speech, a lumbering gait… a lack of “being there” in the eyes that was disturbing… a complaint made by movie patrons about CGI creations in the movie The Polar Express (2004) and the Lord of the Rings trilogy – although in the case of the latter, the soullessness of Gollum was intentional. Some of the most frightening moments in horror movie history have been caused by the mistaken belief that a corpse is a living human, and vice-versa. Perhaps our current identification with zombies is a way of re-navigating the steep dip of the valley as we prepare for a near future of androids. It is hypothesized that the repulsion we feel is a survival instinct kicking in to keep a distance from those individuals who were sick or mentally disturbed. As a new age brings with it persons with new ways of thinking, being and acting, it can be considered important evolutionary work to continue to push the bounds of our humanity zone and embrace our differences rather than exclude them.