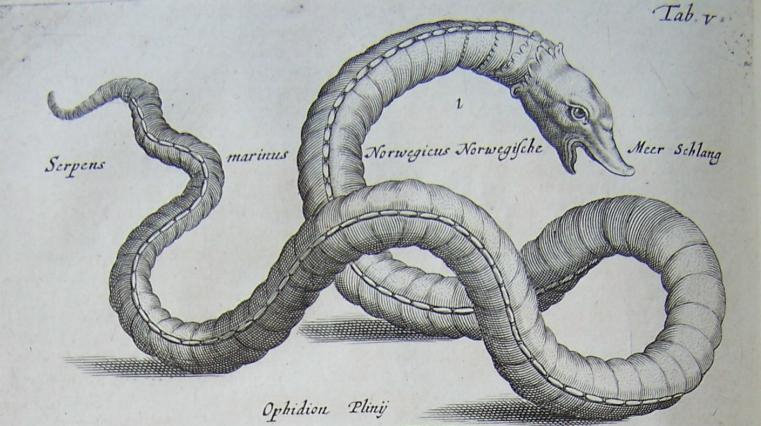

Paul Kingsnorth of the Dark Mountain Project has written an excellent article on 2016, the collapse of failing stories and how the new ones come from the margins. Many of us feel like this year hit us. Hard. Our cultural myths—especially the one where we are climbing, ever-so-assuredly, towards progress, are getting blindsided by what Paul describes as a kind of “anti-historical” resurgence through figures like Donald Trump, neo-fascism and nativist revivals. However, 2016, as a year, a segment of time, isn’t the culprit. The “serpent” hatched long ago. It merely makes its first appearance.

The collapse of our “meta” narratives about culture, history, and eschatology (growth towards goodness, the march of progress, etc.) are challenged by what slithers up from the darkness and crawls out of the sea. Issues like climate change and the ecological crisis loom on our horizon and demand a mythological language to in order to be adequately articulated:

This unashamedly Whiggish view of history has been the standard worldview amongst the opinion-formers of the Western democracies since 1989, but it is now crashing, with a terrible screeching of metal and gears, directly into other notions about how the past feeds into the present. Looked at from a longer-term perspective, as a conservative would patiently explain, there is no moral arc bending in any particular direction. The elites of ancient Rome or the Indus Valley civilisation or Ur of Chaldees doubtless believed that the arc of justice was bending towards their own worldview, too, but it didn’t, in the end.

When I look at the state of the world right now, I see an arc bending towards something that dwarfs any parochial concerns about particular presidential elections or political arrangements between human nations, and which should put those events into deep perspective. I see a grand planetary shift that has not been seen for millions of years. I see that half the world’s wildlife has gone, and half the world’s forests, and half the world’s topsoil. I see that we have perhaps two generations of food left before we wear out the rest of that topsoil. I see 10 billion people needing to be fed. I see the highest concentration of carbon in the atmosphere since humans evolved. I see coming waves of political and cultural turmoil resulting from all of this, which makes me fear for my children, and sometimes for myself.

***

Anyone who has tried to talk to someone with different opinions about the election of Donald Trump, or the British exit from the European Union, or climate change for that matter, will know that there is a madness in the air right now which goes far beyond the facts of any particular case, and which engulfs them until they are lost in the fog. When people argue about Brexit, they are not really arguing about Brexit. When they fight about Donald Trump, they are not really fighting about Donald Trump. These things have become symbols, archetypes of the kind of future we want and don’t want, the kind of people we think we are and the kind of people we think others are. It’s as if we are fighting over myths, stories, representations of the world as it is and as we want it to be.

The answer to these problems is not to hold onto these dying stories—they will no longer be echoed in the royal halls or told by the cultural bards—but to look to the edges of history for new stories.

In a likeness to Charles Eisenstein’s emphasis on changing cultural mythologies, a la ‘A New and Ancient Story,’ and The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know is Possible, or historian William Irwin Thompson’s investigation of new, planetary mythologies in At The Edge of History and Passages About Earth, Paul Kingsnorth reminds us that new stories come from the margins…

Our stories are cracking: the things we have pretended to believe about the world have turned out not to be true. And the serpent has a lot more damage to do yet. In such times, we write to make sense of things, and to examine our stories in their proper perspective. We write new stories because the old ones are half-dead now. We turn from the heat of the anger before it burns us, we let the names fall away, we walk up the mountain, sit down at the summit, breathe – and pay attention.

I think we could make a case that most of the world’s great religions, philosophies, artforms, even political systems and ideologies were initiated by marginal figures. There is a reason for that: sometimes you have to go to the edges to get some perspective on the turmoil at the heart of things. Doing so is not an abnegation of public responsibility: it is a form of it. In the old stories, people from the edges of things brought ideas and understandings from the forest back in to the kingdom which the kingdom could not generate by itself.

Writing in the time between stories

Paul cogently proposes the role of the writer in these historical crisis points: we must be the ones who go out there—to the margins—and write the new stories.

We write new stories because the old ones are half-dead now. We turn from the heat of the anger before it burns us, we let the names fall away, we walk up the mountain, sit down at the summit, breathe – and pay attention.

So what kind of stories are we telling now? We should look to the ones we’re telling ourselves. Forget the tall tales being spun at The New Yorker and other major cultural arbiters. They, of course, can only spin in their place. “Deficient”, as the philosopher Jean Gebser might describe, in their ability to articulate the problem, provide alternative lines of flight towards some new path. For our sake, we should look to the narratives that run headlong into the crisis, that inch closer to it in the imagination of collapse and eco-crisis. We should listen to the philosophers, ecologists, and artists on the margins who will weave words with death and contemplate endings. Those who will watch the verdant take-over of the concrete and pavement and hear what voices are hidden in the silence; seeds planted in the absence of tomorrow. Science fiction stories are abounding with tales from the imaginary Next Day, the fantastical New Story. They tell us about living and dying in the Anthropocene and what kind of futures are possible after the death of the old stories. We should look to them and listen, because through them we learn about ourselves and our own becomings.