The following originally appeared on satyogainstitute.org

It is

impossible to communicate the anguish of impossibility, even though — or

because — it is the central axis of what we quaintly, if unaquaintedly, refer to

as reality. Coming to understand the nature of impossibility is the essence of

education. This is no doubt why Freud said that education is one of the three

impossible professions. The other two are governing and conducting a

psychoanalysis. Freud's successor Lacan went further, and recognized that the

anguish that brings someone to psychoanalysis is nothing but the impossibility

of love, for which there is no cure. He affirmed that impossibility in his

famous apothegm, "il n'y a pas de rapport

sexuel" (there is no sexual relation).

But such assertions of the existence of specific dimensions of impossibility

evade the radical ubiquity of impossibility as the hallmark of existence tout court. Impossibility is always and

everywhere. There is no relation of any kind — not just sexual. Even friendships

are based on illusion. No colleagues are really in the same league. Our words

are riddled with ambiguities, our desires with unconscious conflicts and

counter-desires. Our identities are inauthentic. We are imitations of

imitations. Finding oneself is impossible. Discovering truth is impossible. There

is no credible knowledge. No scientific theory lasts for very long (although

its lifespan can be prolonged by being turned into an ideological given; in

other words, a religious belief, as has happened with Darwinism — which cannot

explain a long list of scientific observations, ranging from the Cambrian

explosion to the fact of eco-systems to the irreducible complexity of even the

most apparently simple microbiological structure). The impossibility of

understanding the world or each other or oneself is at least useful in

deflating the arrogance and grandiosity of the narcissistic ego. Unfortunately,

narcissists can easily remain in denial of their own impossibility for a long

time, until karma catches up with them.

This is what Miguel de Unamuno referred to as the tragic sense of life. It is

the authentic motivating power behind religion. Monks and saints have always

been those who have accepted the impossibility of sexual relationships and

mundane life, and have gone to monasteries to ponder the ultimate meaning of

the impossibility of existence, including the impossibility of the existence of

God. Impossibility, of course, is the mark of the presence of God, since

the world cannot be accounted for through any rational process of cause and

effect. Yet by the same token, God is an impossible concept. This has led, on

the one hand, to rampant agnosticism and, on the other, to the silence of the

Buddha.

Today, in our less contemplative era, we tend to face impossibility with anger

and projection. We see the impossibility of political change (or else we deny

the impossibility, and vote for someone who offers 'change we can believe in,'

and then suffer massive disappointment, but soon look for yet another false

messiah to save us). Yet, instead of recognizing and accepting the

impossibility, we defiantly demand the impossible. We project on ‘the one per

cent' that they are the obstacles to change, when in truth, they are as

helpless as anyone else.

Impossibility is structural. It cannot be changed. We need to learn to live

with it, to understand it, to become it. Only then, as the embodiments of

impossibility, of paradox, of God's diabolical sense of humor, can the way out

be glimpsed. But let us not get too optimistic just yet. To become the

impossible is not so easy. In fact, it too is impossible, but this is where the

silence of the Buddha — and the incisive words of the few liberated sages who

have spoken about the issue — becomes of paramount importance.

Let us assess the issue more rigorously. What follows is a rough outline for a

treatise on impossibility.

We must begin by recognizing that reality itself is an infinite process of

enfoldment and unfoldment of an unknowable implicate order, a la David Bohm. It is impossible to put

limits on that order or its potential. Therefore, impossibility is itself

impossible to assert, except as an empirical observation. The unfoldment

process does tend to demonstrate archetypal moments, or folds. Each fold

reveals a deeper dimension of the Real. The folds, or pleats, must be linked

together in consciousness to unveil the hidden pattern of the implicate order

that the phenomenal plane can only at best symbolize to the very consciousness

that is being observed, in yet another incident of impossibility.

A compleat human life has seven pleats:

1. The innocent ignorance of impossibility

2. The denial of impossibility

3. The hatred and projection of impossibility

4. The anguish of impossibility

5. The acceptance of impossibility

6. The transcendence of impossibility

7. The attainment of the Impossible

In the first pleat, impossibility has not yet been consciously encountered. The

function of the parents is to delay the recognition of impossibility, so that

childhood innocence and joy can flourish, and the young mind has time to

develop resources to cope with the reality of impossibility when it is finally,

inevitably, cognized.

The whole significance of the story of the Buddha is that of the unfoldment of

the awareness of impossibility and its authentic treatment. The young pre-Buddha

is a prince whose father tries to protect the innocent eyes of the son from

seeing images of sickness, old age, and death, but to no avail. The boy

realizes the impossibility of sustained youth and happiness, and he falls into

dejection. But then he spots a wandering yogi, one who has renounced the

pursuit of jouissance for the

achievement of liberation from the realm of the impossible. He immediately

decides to become a yogi.

The meaning of yoga is encapsulated in the Buddha's three tests. He is first

faced with an attack by Kama, the lord of pleasure, in the form of three

beautiful young women who try to seduce him. But he has the sense to ask them

their names, which turn out to be Desire, Satisfaction, and Regret. Upon

realizing that he cannot get one without all three, he renounces sexual jouissance.

Next, the great spiritual warrior is faced with Mara, the lord of fear. He is

not intimidated by the power of the Other, by the prospect of pain and death,

nor by the desire for power over others. He scorns Mara and remains unmoved by

the display of military might. It is Mara who then becomes dejected and

submits.

The fledgling Buddha is then faced with the final test, the guilt tripping by

Dharma. He is a prince; he should be sitting on the throne, acting responsibly,

taking care of the kingdom; at least taking care of his own wife and newborn

son. How can he abandon his karmic responsibilities? Has he no conscience? At

this moment, the Buddha becomes even more deeply cognizant of the impossibility

of his situation, and realizes that the only way out is to dissolve his

identity entirely. Only by not existing can he attain freedom. But what does

not exist is clearly not his body, but the ego. In suddenly seeing through the

illusion of the ego, he becomes the Buddha in fact, not just in potentia, and a new world teacher is

born.

Most of us, alas, are far more reluctant to become buddhas in fact, and need to

be dragged through the pleats of denial, anger, and anguish, before reaching

the bliss of liberation. The price of denial of impossibility is living an

imaginary life, a superficial life, a life led in bad faith, with an

unconscious split-off mind full of skeletons, traumas, and anxieties that can

come out only as physical symptoms, psychological problems, accidents, and

relationship difficulties.

Eventually, with the help of an adept spiritual guide or even a good

psychoanalyst, one can come out of denial without falling into projection and

fury. But otherwise, the route of least resistance is to scapegoat someone else

for the impossibility of love and happiness and fairness and freedom, and to

live in a state of war. Interpersonal conflicts are always the result of

inauthentic existence, the cowardly failure to face the structural presence of

impossibility as the true face of the Real.

Now the phase of mourning begins, the anguish of recognizing impossibility as a

necessary, not contingent, condition of life. At last, one sees through one's

own imaginary narrative of egoic existence, and the futility of carrying on the

façade any longer. But the real anguish comes in the realization that one is

completely lost, that impossibility destroys the compass by which one has

navigated through time. All attempts at maintaining a semblance of meaning now

collapse in waves of anxious depersonalization.

It is at this point that the assistance of an authentic guru, someone who has

gone through this crisis and come out the other side, becomes valuable.

But trying to sustain a relationship with the guru is itself traumatic, since

the guru by definition is no longer a person. He or she is an impossible

object, ungraspable, uncanny, intimate yet utterly unknowable. And yet, you

feel that you are known — and loved — by the guru more deeply than anyone has ever

known or loved you. The relationship, though impossible, brings peace. And when

all else has fallen away, what remains of oneself is only love.

One's own impossibility, and that of the world, can at last be fully accepted.

And this is the real beginning of the spiritual pilgrimage. One becomes a

profound student of impossibility. One comes to appreciate the beauty of

paradox. One is drawn to the art of such creative geniuses as Escher, Dali,

Borges and other masters of paradox. One sees in impossibility the mark of a

superhuman intelligence. In the very chains of the most frustrating

impossibility, one comes to perceive the sublime presence of salvation, the

life breath of our liberating God.

Through surrender to that God who has inscribed impossibility into the very

structure of His Creation, we gradually — or suddenly, in an eternal moment of

satori — discover the patterns of the thought-waves of the mind of the Savior.

Then, in the wake of surrender of the ego mind to God, the created world is

recognized as nothing less than the eternal Tao. No longer is it perceived as

created, but now it is glimpsed rather as dreamed.

Chuang tzu dreamed he was a butterfly; then he awakened, and wondered if he

were really a butterfly dreaming he is Chuang tzu.

Acceptance of impossibility now morphs into transcendence of impossibility. If

it is all a dream, then, as in a dream, all is possible. One becomes as a

little child once more; now one can enter the kingdom of heaven. But where is

the portal?

Innocence must evolve into utter egolessness. The last traces of entityhood

must evaporate in the silence of pure awareness. The mind based in language,

thought, imagery, emotion — must die. The Logos itself must ascend to the

Godhead. The Source of mind is Supramental Intelligent Presence. In full

surrender to the eternal, immovable Presence, the world itself dissolves.

The unsurpassable sage Sri Ramana Maharshi often proclaimed that to the gyani

(one who knows the ultimate truth) there is no world. There are no others. No

creation has ever occurred. This is the perennial doctrine of Ajata-all is

uncreated appearance. Time and space are both illusions. Even the most sublime

notion of God is an illusion. The Supreme Real is not a being.

Give up all concepts, all attempts to grasp, to control, to master. Renounce

even the saintly self that is willing to renounce it all. Realize compleat

Emptiness. This is the unfoldment of the final pleat, the attainment of the

Impossible: the Dreamer of the Dream.

Thou art That. No more should or can be said.

Namaste,

Shunyamurti

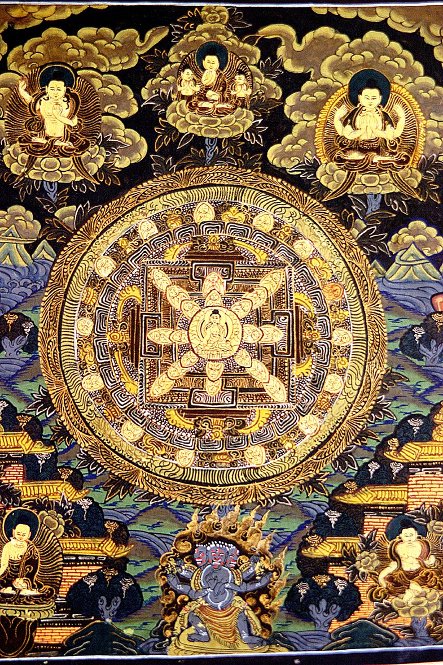

Image by Viajar24h, courtesy of Creative Commons license.