The following is excerpted from the Prelude in The Metaphysics of Ping-Pong, published by Yellow Jersey Press, Random House. The book has been longlisted for the William Hill Sports Book Award 2013.

During a summer some years ago our friend Rupert Sheldrake — the controversial philosopher of science — his wife Jill and their two boys, Merlin and Cosmos, paid us a visit. I gave the boys rackets and showed them a few strokes. It was instant karma: they were hooked. Back in London, they persuaded their father to buy them a table and he himself has become a player. Every time I went to visit them there were the inevitable ping-pong matches. I’d play for hours with both sons and with Rupert, too. It was fun and, surprisingly, also intellectually stimulating. There was something unusual about the essence of the game that escaped us. Eventually, after some speculative discussions about it, we realized what was intriguing us: the fact that ping-pong is strikingly non-Euclidean. I have kept a note that he sent me about it: “Euclidean geometry is the geometry of plain surfaces and three-dimensional space, but non-Euclidean geometry is the geometry of curved surfaces, hence it is indeed an appropriate term for this kind of ping-pong.”

What I took as an official confirmation of my ability as a player came six years ago, on a cruise ship. A ping-pong tournament had been organized. Half-hoping that this would happen, I had brought along my (still preassembled and seldom used) racket. I had just discovered that on a cruise three new factors further complicate the game: the rocking of the ship, the wind on deck, and the… margaritas. But the tournament was held while the ship was still docked; in a sheltered spot undisturbed by wind; and no alcohol was served on board while in port. The tournament turned out to be uneventful: no opponent gave me a hard time and I won.

So, even if I no longer owned a table and played rarely, ping-pong seemed to catch up with me constantly. By the time it did for good, it suited me all the more because meanwhile I had been cultivating the art of thinking unconventionally. During my university years first in Pavia then in LA at USC, between classes I’d go to one of the libraries on campus and read — avidly — the Encyclopædia Britannica at random. Everything interested me, but ultimately nothing satisfied me. Disappointed by the canon taught at school and broadcast by the media and the establishment, by the time I graduated I was already delving well beyond it. For years I’ve been exploring a different sort of knowledge. Sufism, for example, shows one how to escape from the “prisons of linear thinking.” And so, in different ways, do Taoism and Zen.

To illustrate an instance of escape from the “prisons of linear thinking,” I won’t use a passage from some ancient esoteric text, but a TV commercial for “Instant Kiwi,” a lottery scratch card from New Zealand — sometimes this kind of thinking hides itself in the most unsuspected of places.

Students are taking an exam. A rather pompous Professor is watching them while the clock is ticking. “Time, thank you,” he eventually says. “Put down your pens and bring your papers to the front of the room.” All students do so but one; he’s wasting time scratching an instant lottery ticket, but he could be finishing the exam. This one student reaches the desk to turn in the exam past the allotted time. The Professor says: “I’m sorry, too late.”

The student is dumbfounded.

“I gave you plenty of warnings about time,” resumes the Professor, “you failed. Sorry.”

“Excuse me,” says the student in a matter-of-fact tone, “do you know who I am?”

The Professor, contemptuously: “I have absolutely no idea.”

“Good,” says the student, and places his paper in the middle of the stack.

This catches us by surprise. But it’s more than surprising; it’s mind-bending. One feels that logic is being violated, and with it the laws of linear thinking. To be totally unknown is very desirable. In fact, thanks to his anonymity, the student still manages to hand in his exam. Furthermore, the Professor is making the wrong assumption as he replies to the student. In fact, he, the Professor, is being tested, and he is the one who fails.

Down the centuries Taoism, Zen and Sufism have created a large repertoire of short and seemingly mundane stories whose goal is that of violating logics and challenging our assumptions. Twentieth-century traditionalists have done much of the same, by turning received notions upside down. Ping-pong, as I will show, has so many baffling and refreshingly illogical qualities about it that, whenever I happened to play an occasional game, somehow it echoed inside me in a new and increasingly more resonant way. And as a result of that I marveled all the more at how magical it was to spin that little ball and make it fly, bounce on the table and off the opponent’s racket in mysterious ways.

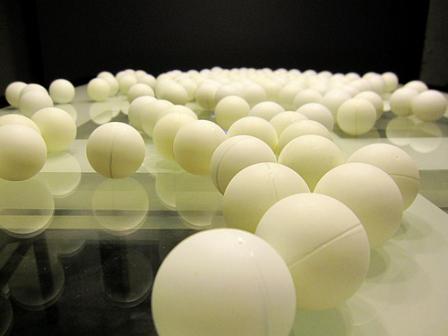

Teaser image by mknowles, courtesy of Creative Commons license.