It's 1976, and I'm speaking to Karen, my partner at the time, bemoaning my lack of commitment to anything. All of my close friends over the years, up to and including my wife, Shari, will attest to the fact that I am a habitual bemoaner. (Bemoan: "To express grief or disappointment about something." In Yiddish, it is translated to "kvetch," which adds the elements of whining and complaining. It could be argued that, depending on my audience, I am both a bemoaner and a kvetcher.)

In any event, those with the supernatural ability to see auras and animated cartoon icons appear in real life would have seen a light bulb pop on over Karen's head as she had a sudden, revelatory insight into my character. "You have a very strong and consistent commitment," she said. "You're committed to suffering!"

Yes!, I thought, at last. She was right on target, and naming my condition brought with it a huge wave of relief. After floundering about in my early 20s searching for a focus, I had finally zeroed in on something to which I was already quite devoted, and which seemed to come to me naturally: suffering, and seeking a way out. Little did I know at the time how extensive the profession of suffering was; endless work had already been done in the field for thousands of years within schools of philosophy and ancient religions, traditional approaches to psychology and contemporary alternative therapies, legal and illegal pharmaceuticals, New Age teachings, mysticism, and more.

I was in way over my head and had a lot of catching up to do, and would spend the next 30+ years becoming an expert in both misery (my own) as well as the innumerable avenues of relief being shouted from the rooftops by True Believers in one system or another. Or those that were more quietly delivered in the privacy of the therapist's office, or in communities of spiritual seekers and their enlightened masters in ashrams, zendos and monasteries all over the world. Or through the many forms of meditation and approaches to prayer, techniques of affirmation, positive thinking, Rebirthing, primal screaming, encounter groups, Gestalt Therapy, Bioenergetics, intensive seminars like EST, and body-oriented modalities like Rolfing. The list of things I explored goes on and on and on, and included extended pilgrimages to India, silent retreats in Nepal, the study of Kabbalah in Jerusalem, and ayahuasca rituals in Brazil.

I literally made a career out of my search, and as a journalist, I became a human guinea pig for any and every carrot held out to the suffering human. Over time, the object of my seeking evolved from merely looking for personal relief, to a grander, all-encompassing search for truth, God, and enlightenment. Thus I found myself on a spiritual path. But I have always been a rather delinquent aspirant. I tend to spiritually binge: I'll spend 40 days alone on a mountaintop or 20 days on a meditation cushion in silence, but whenever I return home from such adventures, I always seem to take myself with me and leave the practices behind, especially if they worked.

For how could I pursue my chosen career path if I actually found what I was looking for? The two are mutually exclusive. The bad news for unhappy people is the recognition that we are wrong about everything we have always pointed to as the source of our suffering, and then we have to confront the fact that our entire personalities have been erected on that inaccurate foundation. That is why enlightenment, when it occurs, is earthshaking, and why, for those of us committed to our suffering, enlightenment is it to be avoided at all costs.

We spiritual seekers always imagine that enlightenment is akin to winning the spiritual jackpot, when it is actually a rather humbling and personal invalidation of who one believes oneself to be, which for most of us, as George Bernard Shaw put it, is often simply a "bundle of grievances and ailments."

My individual unhappiness eventually expanded to include the fundamental, core discontent at the root of all beings everywhere, and I found that Buddhism stated the problem most succinctly: life itself, Buddha taught, inherently contains suffering and dissatisfaction. It's just part of the package, part of what we were given as a door prize, just for showing up. (Thanks a lot, Buddha.) The source of our suffering, Buddhism explains, is that we either don't get what we want, or we get what we don't want, or we do get what we want and then have to face the pain of losing it due to the ineluctable impermanence of all passing phenomena. Therefore, we would all be wise to relinquish any strongly-held attachments to which we might be clinging, those positions that insist that life should be a way that it isn't. In fact, for beginners on the path of suffering, this is a surefire method to maintain an unhappy disposition: simply demand that your life, and all life, be different than it is. Bingo!

Spiritual matters aside, though, in the psychological realm, it became pretty clear to me that since childhood, I have suffered from repeated and ongoing bouts of clinical depression and nearly continuous anxiety. A few other diagnoses were tossed my way over the years by mental health professionals, including "Borderline" and "Bipolar II Spectrum Disorder," which, sadly, was described to me as the kind of bipolar where you only get to experience the depressive side of the see-saw. It sounded unipolar to me. Apparently there is a distinction between ordinary depression and bipolar depression, but all I knew is that I felt ripped off and deprived of the manic part. (I was depressed about the type of depression I had. Actually, none of the diagnostic labels have ever felt quite accurate to me, but what do I know? I always preferred "Second Generation Holocaust Survivor Syndrome," but obviously that's a whole other story.)

Despite the Buddha's explication of the all-pervasive nature of suffering, it is clearly not distributed equitably. Some people suffer more than others. "I was complaining that I had no shoes," the saying goes, "then I met someone with no feet." On the other side of the equation, I myself have met many people who, I could swear, seem to simply go about their lives without a lot of fuss, neither bemoaning nor kvetching, and even seem to be enjoying themselves much of the time. They've never been to see a therapist, never tried Prozac or needed Xanax to get out the front door, and have no use for God or religion. Such people seem like alien beings to me. I can't quite get my head around what their moment-to-moment experience of living actually feels like. For example, my friend Asha once said to me, in passing, "You know the way you feel when you feel really deep down fine?" I didn't hear whatever she said next, because I was thinking, Huh? Feeling what? Deep down fine? Really? She had lost me.

William James addressed this disparity in The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which he distinguished between the "once-born" — those pesky people with the native, happy temperaments — and the "twice-born," the rest of us who need a little help to get with the program (I'm paraphrasing). ‘Course James himself wasn't exactly the most cheerful pretzel in the party mix, at least not before he discovered nitrous oxide, the experience of which would eventually lead to his oft-quoted declaration, "…our normal waking consciousness…is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different." (Unfortunately, the only reports he delivered directly from these other forms of consciousness, whilst under the influence of nitrous, were some rather vague journal entries, the most explicit of which was "Oh my God, oh God, oh God!")

At the end of the day, suffering comes down to our steadfastly, and often unconsciously, holding to a core point of view that somehow just who we are, and just how life is, is fundamentally not okay and should be different. That is the lens through which we view existence, and we are usually blind to it, and thus, rather than changing the lens, we devote ourselves to perpetually rearranging the picture, via the various and exotic forms of our seeking.

True sanity is parted from us by the filmiest of screens, only a thought away, and we all know this directly from those glorious moments of being "in the zone," when that "not okay" voice of the perpetual seeker mercifully drops away and allows us to engage life directly and fully, as it is, making neither demands of life nor imposing conditions on it. Those are moments when we are launched, despite ourselves, into the Grace of joy, gratitude and appreciation of the Great Mystery that surrounds us always. May we all know more of those moments.

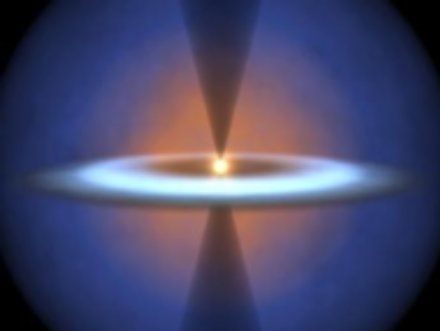

Image by The Bright and Morning Star, courtesy of Creative Commons license.