This article first appeared in Mavericks of the Mind, recently published by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

Oscar Janiger was born on February 8, 1918, in New York City. He received his MA in cell physiology from Columbia, and his M.D. from the UC Irvine School of Medicine, where he served on the faculty in their Psychiatry Department for over twenty years. His research interests have been wide, and he describes himself as a “tinkerer.” He established the relationship between hormonal cycling and pre-menstrual depression in women, and he discovered blood proteins that are specific to male homosexuality. His studies of the Huichol Indians in Mexico revealed that centuries of peyote use do not cause any type of chromosomal damage. He is perhaps best known for establishing the relationship between LSD and creativity in a study of hundreds of artists. In addition to his research interests he has also maintained a long-standing private psychiatric practice, which he continues to this day.

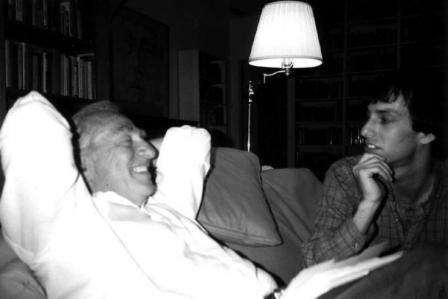

Back in the late fifties and early sixties when LSD was still legal, Oscar incorporated LSD into some of his psychedelic therapy, and is responsible for “turning on” many well-known literary figures and Hollywood celebrities, including Anais Nin and Cary Grant. More recently Oscar has been involved in studying dolphins in their natural environment, and is the founder of the Albert Hofman Foundation–an organization whose purpose is to establish a library and world information center dedicated to the scientific study of human consciousness. He has also just completed a book entitled A Different Kind of Healing, about how doctors treat themselves. Jeanne St. Peter and I interviewed Oscar in the living room of his home in Santa Monica on January 3, 1990. Surrounding virtually every wall in his house is the largest and most interesting library I’ve ever encountered. Oscar spoke to us about his scientific research, creativity and psychopathology, the problems he sees with psychiatry, and his discovery of the psycho-active effects of isolated DMT. Oscar is an extremely warm, highly energetic man. There is a deep sincerity to his manner. He chuckles a lot, and one feels instantly comfortable around him.

DJB: Could you begin by telling us what it was that originally inspired your interest in psychiatry and the exploration of consciousness?

OSCAR: I was about seven years old and I was living on a farm in upstate New York. The nearest neighbor was a mile away. I would go for a walk, visit them, play, and then come home in the evening. This was a wild kind of country setting, and I had to get home before dark. Some evenings I would be coming home and the scene around me on the path was filled with menacing figures; pirates and all kinds of cut-throats ready to grab me and do me in. There was a place I called the sunken mine, where people had supposedly drowned and there was a frayed rope hanging from a tree. All of these menacing things gave the evening a very sinister cast, and I’d finally run to get home. Certain evenings I’d make the trip, and everything was just light and airy. Things around me were filled with joy and pleasure. The birds were singing, rabbits, squirrels and other animals were having a wonderful Disneyland time. So one day I was thinking, My God, that’s a magic road! One time it’s this way, another time it’s that way. So I puzzled over that. I finally came to the conclusion that, if it wasn’t a magic road, then I was doing something to these surroundings and if I was doing it then I could change it. So the next time I came back from my neighbour’s place, and everything got murky, strange and sinister, I said, “No! If I’m doing this then bring back the rabbits, bring back the squirrels, bring back the fairies and let’s lighten this thing up.” Sure enough, it changed.

That was the beginning of my interest in consciousness. It was all crystallized into a marvelous saying from the Talmud – “things are not the way they are, they’re the way we are.” From then on, when I’d get into situations, I’d determine what aspect that was within me was being projected outward, and what was a reflection of the world that others can validate along with me. That, of course, has been the theme of my work in therapy and as a scientist. The important distinctions regarding projection are among the fundamental things that one has to solve to understand how people behave and the contradictions in their behaviour. Other inspirations are simply those of curiosity. I was enormously curious about how things worked. I was always asking why? why? why? Then I got to medical school and the why extended to the brain and the activities of the nervous system, which seemed to me to be the largest why of all. Also, I had personal experiences with people who had become, I guess you’d say, psychotic, or who acted bizzarrely or strangely. These matters have been of great interest to me.

How do you define consciousness?

Well, I was afraid you were going to ask me that. When you say define something, I’m caught between what I recognize as the accepted definition – the sources that come out of dictionaries, legal definitions and all that stuff that belongs in the pragmatic world – and the definitions that come from my intuition. The Oxford English Dictionary offers at least six or seven varieties of definition for consciousness, and several have entirely different connotations. When you get down to contradictions like being conscious of one’s unconscious, it gets pretty strange and labyrinthine. I would say the conventional definition contains the idea of being aware of one’s self – a sort of self-reflection. Or you can describe it operationally as being the end product of a complex nervous system that eventually produces a state that allows us to be in some way congnizant of ourselves and the enviroment. It allows us to extrapolate into future events, into past events, and allow us to take a position in one’s imagination so we can examine realities that are not responsive to the ordinary, daily context of the world around us. Many of these things require qualifications, but let me then stay with the word as something that gives us a feeling that distinguishes us as individuals, that gives us a sense of self, and sense of self-reflection and awareness.

You’ve used the term “dry schizophrenia” in desribing a creative artist. Could you explain what you mean by this and what similarities and differences you see between certain aspects of madness and the process of creativity?

Well, of course that’s always been on my mind. I remember that I could make the wallpaper do all kinds of tricks when I had a fever, and I could sit – if you’ll excuse me – on the john, and watch the tiles recompose themselves and make patterns. Therefore I suspected that there was a part of my mind which had a certain influence over the world around me, and that, under certain conditions, it can take on novel and interesting forms. The dreams I had were very vivid, very real, and there were times when I found it hard to distinguish between the dream life and what we might call the waking life. So there was a very rich repository of information that was somewhat at my disposal at times, sometimes breaking through at odd moments. I later on thought that could be a place that one could draw a great deal of inspiration from. So I studied the conditions under which people have these releases, breakthroughs, or have access to other ways and forms of perceiving the world around them and changing their reality. When I studied the works of people who profess to go to creative artists and ask them how they did it and what it was about, I realized that what we had by way of understanding creativity was a tremendous collection of highly idiosyncratic and subjective responses. There was no real way of dealing with the creative process as a state you could refer to across the board, or how one could encourage it.

That’s how I got the idea for a study in which we could deliberately change consciousness in an artist using LSD, given the same reference object to paint before and during the experience. Then I would try to make an inference from the difference between the artwork outside of the drug experience and while they were having it. In doing so I was struck by the fact that the paintings, under the influence of LSD, had some of the attributes of what looked like the work done by schizophrenics. If you would talk to the artists in terms of the everyday world, the answers would be very strange and tangential. Then I began to look into the whole sticky issue of psychopathology and creativity. I found that there are links between the creative state and certain qualities that people say they have when they’re creating, that were very much like some of the perceptions of people who were schizophrenic or insane. I began to notice what made the difference. It seemed that the artists were able to maintain a certain balance, riding the edge, as it were. I thought of creativity as a kind of dressage, riding a horse delicately with your knees. The artist was able to ride his creative Pegasus, putting a little pressure on his ability to control the situation, enabling him to just master it, while allowing the rest to flow freely so that the creative spirit can take its own course. The artist is faced with the dilemma of allowing this uprush of material to enter into their conscious mind, much like trying to take a drink from a high-pressure fire hose. This allows them to integrate their technique and training, and still be able to keep relatively free of preconceived ideas, formulated notions or obligatory reality. In that state they were able to harness it enough so that the overriding symptoms of psychosis were not present, but every other aspect of their being at that time seemed as though they were in a semi-psychotic state. So I evoked the term, “dry schizophrenia” where a person was able to control the surroundings and yet be “crazy” at the same time, crazy in the sense that they could use this mode of consciousness for their work and creative ability.

There’s a lot of documentation about psychopathology and creativity but I think it’s all from a central pool, kind of a well-spring of the creative imagination that we can draw from. It equally gives its strength to psychosis in one sense, or breaks through in creativity, theological revelation in the world of the near-dying and people who are seriously ill, and so on. All of that provides us with a look into this cauldron, this very dynamic, efficacious part of the brain, that for some reason or other is kept away from us by a semi-permeable membrane that could be ruptured in different ways, under different circumstances. I recall reading that James Joyce had a daughter named Lucia who was schizophrenic. She was the sorrow of his life. Upon persuasion from Joyce’s patron, both of them were brought to Carl Jung. This was against Joyce’s wishes because he didn’t like psychiatrists. Jung examined Lucia, then finally came in and sat down with Joyce. Joyce said to him that he thought Lucia was a greater artist and writer than he was. Can you imagine? So Jung said, “That may be true, but the two of you are like deep-sea divers. You go into the ocean, a rich, interesting, dramatic setting, with your baskets, and you fill them up with improbable creatures of the deep. The only difference between the two of you is that you can come up to the surface, and she can’t.”

Basically it’s like the difference between being able to swim in the ocean or being….

Caught by the waves and dashed to pieces, right. There’s a wonderful book that describes the process of this ever-changing remarkable flux of consciousness that Sherington called “the enchanted loom.” It’s called The Road to Xanadu by John Livingston Lowes. I recommend it highly as an exercise in the ways of the imagination.

Could you tell us about the thought-experiment that you devised to categorize what you refer to as “delusions of explanation?”

Imagine that someone is taken quietly at night while they’re sleeping, out of their bed, and are then deposited in one of the most unearthly places on the planet — Mammoth Cave. We found by repeated experiments that upon awakening, there are only five explanations that someone in a Western culture would come up with and I refer to these main headings or rubrics as “delusions of explanation.” They are: (not in order of frequency) I must be dead, I must be dreaming, someone or something has played a trick on me, I’ve gone crazy or I am in Mammoth cave. Through my experience in mental hospitals, I’ve found that schizophrenics will try to explain the extraordinary nature of their experience by using one of these basic rubrics. In our culture explanations for unexplainable phenomena are rather sparse. My supposition is that other cultures may have different explanations for such phenomena.

What are some of the main problems that you see with the state of psychiatry today and how do you think we can improve it for the future?

I think that the material emphasis of psychiatry and neuropathology of the last century, where everything was reduced to the simplistic notion of the mind as a switchboard, and all illnesses were the result of pathological processes in the brain itself, didn’t set well. It did not provide a dynamic framework for understanding human behavior. So when the emphasis changed, and Freud and others came on the scene for modern dynamic psychology, I suspect the pendulum swung equally too far in the opposite direction. The heyday of psychoanalysis and depth psychology then ushered in a kind of behavioral construct that seemed to be dependent only upon the dynamic thought process, and left very little to any kind of physical explanation. So I think we were trapped in constant psychological formulations of all our behavior. This was mirrored very well in my own studies. I was interested in finding out the way that the chemistry of the brain and the state of the body influences our thoughts and the way we feel.

The trouble was I coudn’t find a suitable research prospect. I couldn’t get a definitive case where I could show that the state of the body influenced thinking and feeling in a specific way. That was supplied serendipitously by a lady who came in and told me that a week prior to her period she experiences profound depression. Suddenly a light went on and I said, “That’s what I’m looking for!” I realized that an optimal experimental subject for human behavior was a woman because of her menstrual period. She is a wonderful biological metronome that you can count on because of this reliable episodic lunar event. So using that concept, I began to plan a series of behavioral events employing this strategy. I found that some women regularly, about a week before their period, have terrible changes in their general demeanor: their behavior, feelings and thinking. I made a study of three or four good clinical subjects, who went into serious states of mental change around that time. In studying them I was struck by the fact that all of them seemed compelled to give me psychological explanations of their behavior. For example, a woman would say, “Well, I had a fight with my husband yesterday, that’s what made me depressed.” And I said, “Yes, that’s interesting because you had a fight with him last week and it didn’t make you depressed. And every month you have a fight with your husband exactly at the same time and you get depressed.” She agreed, it seemed very odd. So then I went to the psychoanalytical texts. They explained this phenomena by saying, well a woman is afraid that in a week or so she’s going to bleed. This suggests to her that she is being castrated and her penis was removed, so why shouldn’t she be depressed? (laughter) Another analytical interpretation is that this fear is a ubiquitous reminder of her feminine identity and that she was therfore inferior. That’s a good one. (laughter)

I decided to use progesterone as a means of seeing if I could break into the problem of premenstrual depression. I took this woman and I presented her case to my residents when she was depressed. I said, “I’m going to allow you to ask her any question you want, except one, which I’ll keep to myself.” At the end of the presentation I asked the group, “Well, what do you make of this woman?” These residents, who knew quite a bit of psychiatry said, “There’s no question that she has classical clinical depression.” Since pure progesterone is not absorbed through the gut, you have to give it either by injection or vaginal suppository. So I devised an experiment. I double-blinded my progesterone. I injected the material randomly and didn’t know which was which. Then I charted the symptoms and found, when I broke the code, that progesterone had an extremely salutory effect in relieving these women of premenstrual symptoms. I began to see clear evidence of a substance in the body that, in short supply, was markedly influencing the behavior of these women. I gave a talk before the Medical Society and outlined what I had done. I said that premenstrual depression could best be treated by looking at this as a hormonal problem, and that it had certain implications for the way the body influences the mind. The people in the group were skeptical and some said, “How do you know that it isn’t some unconscious factor that’s still operating regardless?” They said, “You haven’t proven that she still isn’t worried about her castration fears. You’ve only proven that if you give her progesterone, that could be modified, but you haven’t attacked the basis of the problem.” How could I do that? Psychoanalysis has an answer for everything.

I went to two of my brightest women medical students, and I asked, “How would you like to spend the summer in Europe? I want you to go to all the primate centers there, and find out, do great apes have a menstrual cycle similar to humans? I want you to talk to the keepers and find out if they have any reason to suspect that their behavior is any different during their menstrual cycle.” For the next three months I had letters from all the European zoological gardens. We were excited to discover that in the Berlin zoo, Fritz, who took care of a female gorilla named Olga said, “A week before her period I can’t get near Olga, she’s just a mess. All she does is throw all kinds of shit at me.” (laughter) At my next opportunity to present I said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I have discovered that the gorillas have feminine identification problems, and they also have castration fears, (laughter) because they can get very upset before their period.” Everyone applauded and started to laugh. That was the beginning of my understanding of how mental and emotional difficulties could be correlated with one’s biochemistry. This is the basis for the treatment of depression by altering one’s neurochemistry.

Why do you think that there’s such a fear and resistance against using chemicals to heal the mind?

We’re a drug-phobic culture. It’s a contradiction in terms because we consume more drugs than in any other country. We make a strange distinction between various kinds of pills. Somebody ought to do a research paper on that, on why certain pills are acceptable and others are not. You see people who take handfuls of vitamins in the morning, and they go to a herbalist and take herbs which they know nothing about. But many have great reservations about “drugs.”

JEANNE: What is your view on bridging alternative medical modalities, such as acupuncture and herbalism, with modern methods?

For ten years I was Research Director on the board of an organization call the Homes Center. We gave sums of money to scientifically validate unconventional and unorthodox treatment methods. So you can see where I’m at. The Homes Center was the first and for a long time, the only organization to be doing that. One of the grants was for Stephen LaBerge’s work in lucid dreaming. Some of the other work we funded was in support of energy healing, biofeedback and acupuncture. So I’m very much in favor of the scientific exploration of alternative methods, but not just accepting them unreservedly without discrimination.

DJB: Oz, you’ve worked with and interacted with many of the outstanding minds of our time. Who have been some of the most important influences in your development and where have you found inspiration when you needed it?

Well, Aldous Huxley has been a real source of inspiration to me. Let me give you an example. I was on the stage of the Ebel Theater as part of a three doctor team, to examine a man who professed to be able to lower his blood pressure, stick pins through his cheeks, and remain buried alive in some way where he could get no air. I was to examine him, along with the other two doctors, to see that he wasn’t faking. He stuck a hatpin right through his hand. It didn’t bleed, and we reported that dutifully to the audience. He said he would then lower his blood pressure to 50 over 30, a level at which I felt a person couldn’t live. I took his blood pressure and it was high – about 180 over 110, and I reported that. Then he huffed and puffed and went into a trance. He got rigid, and then we took his blood pressure again. It was 110 over 70 and I reported that to the audience. That evening we met with Aldous, his wife Laura, Anais Nin and her husband Rupert, and this issue came up and I recounted my experience at the theater that morning. And then I said, “So you can clearly see that this man was faking. He said he would lower his blood pressure to 50 over 30, and he didn’t.” I went on to lament that so many of these so-called miracle workers are charlatans. I was very self-righteous. Then Aldous looked at me. He said, (with a British accent) “Dr Janiger.” I said, “Yes?” He said, “Don’t you think it was remarkable that he was able to lower it at all!” (laughter) A light went on in my head. From that moment on, I got a lesson that I always remembered.

Then there was Alan Watts, who I had the good fortune to know and to be his physician for part of his life. He was a remarkably intelligent man, probably the best conversationalist I ever met. A witty, very open, candid person — great guy. He lived his life to the hilt. We went to see one of his television shows in which he was a featured guest. The audience was filled with hippy-type kids and everyone was fascinated. During the performance he was smoking these little cigarellos, they’re like little round cigars. So at the end of the performance a hand shot up. “Mr. Watts. You tell us about life, and how to be free and liberated. Then why are you smoking these terrible cigars?” Old Alan, when he would get excited, one of his eyes would drift over to the corner of his head. He had this funny look and I knew something was coming. He looked at the young man and he said, “Do you know why I smoke these little cigars? Because I like it!” (laughter) So that’s Alan for you, and it tells the story of his whole life. If that’s Zen, more power to him. Then there were people I didn’t know, but read. Great influences were Joyce, Camus and Bertrand Russell. These were people who meant a lot to me. An incomparable writer named B. Travin added a lot to my understanding of human nature. I get more from what great minds have written about human behavior, than any psychiatric text. Sometimes I feel that I have learned more psychology from Dostoevsky and Conrad than I have from Freud. I approach my practice that way: by interacting with people as if they were protaganists in their own dramas.

JEANNE: How has your experience with psychedelic drugs influenced your life, your work and your practice?

In a word — profoundly. It really took me out of a state in which I saw the boundries of myself and the world around me very rigorously prescribed, to a state in which I saw that many, many things were possible. This created for me, a sense of being in a kind of flux, a constant dynamic equilibrium. I used a phrase at that time to designate how I thought of myself at any given moment. It’s a nautical term called a ‘running fix’. It means that when you report your position in a moving vessel, you are only talking about a specific time and circumstance — the here and now. The illusion of living in one room has now given rise to the illusion that there are a great many rooms. All you have to do is get out into the corridors, go into another room, and see what’s there. Otherwise you’ll think that the room you’re living in is all there is.

DJB: Could you tell us about your discovery of DMT?

Yeah! (laughter) It is a psychoactive ingredient of the hallucinogenic brew they use in the Amazon called Ayahuasca. An analysis by chemists revealed that it contained a substance called dimethyltriptamine, DMT. This was unusual because it was almost identical to a chemical found naurally in the body, and it didn’t make sense that we’d carry around with us such a powerful hallucinogen. Nevertheless, a friend of mine, Parry Bivens and I, purified some dimethyltriptamine. We had it all set up one evening. It was thought to be inactive orally by itself. To be on the safe side, we thought we’d inject it into one another the following day. So Parry said he’d see me in the morning and we’d go ahead and try it out. We had nothing to go by as it had never been used before. So when Parry left me I was in the office looking at these bottles, and I got this devilish thought that I should take a shot of this stuff. But I had no idea of how much to take. So I said, like Hofmann, I’ll be conservative and take a cc. I backed myself up to the wall until I could go no further so (laughter) I had to inject myself in the rear.

And from then on — Man, I was in a strange place, the strangest. I was in a world that was like being inside of a pinball machine. The only thing like it, oddly enough, was in a movie called Zardoz, where a man is trapped inside of a crystal. It was angular, electronic, filled with all kinds of strange over-beats and electronic circuits, flashes and movements. It looked like an ultra souped-up disco, where lights are coming from every direction. Just extraordinary. Then I’d go unconscious, the observer was knocked out. Then the observer would come back intermittently, then go back out. I had a sense of terror because each time I blacked out it was like dying. I went through this dance of the molecules and electrons inside of my head and I, for all the world, felt like a television set looks when on between pictures. Finally I lay on the floor, time seemed endless. Then it lightened up and I looked at my watch. It had been 45 minutes. I’d thought I had been in that place for 200 years. I think what I was looking at was the architectonics of the brain itself. We learned later that that was an enormous a dose. Just smoking a fraction of this would give you a profound effect. So in that dose range I think I just busted everything up. (laughter) Parry came back the next day, and he said, “Well, let’s try some.” I said, “I got to the North Pole ahead of you.”

I hear you’ve been doing some interesting work with dolphins and Olympic swimmers. Perhaps you could tell us a little about this project.

Albert Stevens, Matt Biondi and I, got the idea several years ago that we might find an innovative way of approaching wild dolphins, by using Olympic swimmers — the best in the world. It is difficult to study wild dolphins because they are free-ranging and peripatetic. We went to where the dolphins were reported to be, fifty miles off the coast of Grand Bahamma Island. We waited. When they came we jumped in with them, and did a great deal of underwater filming. We studied the film to try to find out how the dolphins behave, and we’re still in the process of doing that now. We did it for three years and developed a good working relationship with these dolphins whom we were now able to identify. Dolphins are strange and beguiling creatures. Their language seems totally incomprehensible, as we know our own language to be nothing like it whatsoever. It appears to be a different order of communication. What stories the dolphins could bring back from their alien world of water if we could only communicate with them.

The final question. Could you tell us about the Albert Hofmann Foundation and any other current projects that you’re working on?

Well, I co-founded the Albert Hofmann Foundation about three years ago. I was involved in LSD research from 1954 to 1962. During that time I accumulated a large store of books, artwork, papers, correspondence, tape-recordings, news-clippings, research reports and memorabilia which probably represented a fair sample of what went on in the psychedelic history of Los Angeles and elsewhere. I was aware that there is a great deal of this kind of information that is scattered and isolated and in dager of being lost or destroyed. Collected and organized this would provide an extremely valuable resource for future research and historians. I was approached by several people who were committed to preserving these unique records. We formed a non-profit organization that we felt was fitting to be named in honour of the man who discovered LSD and psilocybin – Albert Hofmann. He was most gracious in his acceptance and pledged his whole-hearted support. It is based in Los Angeles and functions soley as a library, archive and information center at this time. We have collected a great deal of relevant material from the poineers of psychedelic research, e.g. Laura Huxley, Allen Ginsberg, Stan Grof, Humphrey Osmond and many others. I got back an enthusiastic response from most of the leaders of this movement.

The foundation provides the only open forum for the legitimate discussion of these issues. It offers a place where people can discuss ideas about their own experiences under these various agents. I was surprised to learn how many people out there are closet psychedelic graduates. I’ve talked to people who I thought that never in a million years would understand what I was talking about. “Oh my, it was a wonderful experience!” said a sixty-five year old professor of Medieval French, and I couldn’t believe that she had said that. There’s plenty of them out there, so we’re bringing them together and many of them have become members in our organization. Other projects? I’ve been working in several non-profit organizations that have some concern for the ecological welfare of the Earth. One is called, “Eyes on Earth,” and another is called, “Earth Anthem.” Eyes on Earth involves a scientific visualization of the Earth and its resources. It is the only true cloud-free picture of the Earth, projected electronically onto a huge globe. It was painstakingly assembled by the photographs of the Earth without clouds taken by satellite and it depicts how different resources are dwindling and being depleted. Earth Anthem is a contest for people throughout the world, to find an anthem that represents the earth. This project will culminate in a program designed to celebrate the finalists of this contest. We want to find a song that is representative of the earth, one that we could sing if the Martians come. (laughter) In addition, my new book — A Different Kind of Healing — is in publication by Putnam and is to be released shortly. So that’s what I’m up to, and I keep moving. I think Einstein said it, “Keep moving!”

This interview by David Jay Brown and Jeanne St. Peter is an excerptfrom the second edition of Mavericks of the Mind,

which was recently published by the Multidisciplinary Association for

Psychedelic Studies(MAPS), and is available on Amazon. Loaded with new

material–a new introduction, additional interviews, as well as new

photos and artwork–the second edition of Mavericks of the Mind also

includes the transcripts from the events that brought together

interviewees from the book to debate philosophical topics in roundtable

discussions. This stimulating collection features in-depth conversations

with accomplished thinkers, such as Terence McKenna, Laura Huxley,

Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, John Lilly, Carolyn Mary Kleefeld,

Rupert Sheldrake, Riane Eisler, and Robert Anton Wilson. The

interviews explore such fascinating topics as the frontiers of

consciousness exploration, how psychedelics effect creativity, the

relationship between science and spirituality, lucid dreaming, quantum

physics, morphic field theory, interspecies communication, chaos theory,

and time travel.

“Oscar Janiger with David Jay Brown, Santa Monica, 1993” by Carolyn Mary Kleefeld.