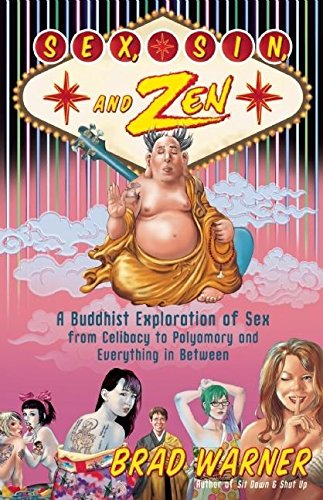

The following is excerpted from Sex, Sin and Zen: A Buddhist Exploration of Sex from Celibacy to Polyamory and Everything in Between, just out from New World Library.

Let’s start out by clarifying some of our terms. Although Zen Buddhism is probably the most talked about form of Buddhism among Westerners these days, it also seems to be the least practiced one. Very briefly, Zen is a specific form of Buddhism that developed at the beginning of the Common Era around five hundred years after Gotama* Buddha’s death as a reaction to the way Buddhism had strayed from its origin as a meditative practice and become more of a religion. The Zen movement sought to strip away all the inessential rituals, costuming, and other trappings and get back down to basics. This is evident in the name of the sect. “Zen” is the Japanese pronunciation of the Sanskrit word dhyana, meaning “meditation.”

Not all Buddhism is Zen, however. I don’t have the statistics, and as far as I know nobody else does either, but my educated guess, based on what I’ve seen and read, is that Zen is a fair ways down the list after Soka Gakkai, Pure Land, Tibetan, and Vipassana Buddhism in terms of popularity in the West. So if you walk into a random Buddhist center in your town, chances are it might not be a Zen temple — unless you live in Minneapolis-Saint Paul or in the San Francisco Bay Area, where there is either a Zen center or a Starbucks on every corner.

Not all Buddhism is Zen, however. I don’t have the statistics, and as far as I know nobody else does either, but my educated guess, based on what I’ve seen and read, is that Zen is a fair ways down the list after Soka Gakkai, Pure Land, Tibetan, and Vipassana Buddhism in terms of popularity in the West. So if you walk into a random Buddhist center in your town, chances are it might not be a Zen temple — unless you live in Minneapolis-Saint Paul or in the San Francisco Bay Area, where there is either a Zen center or a Starbucks on every corner.

A lot of Americans I meet are surprised to discover that there are often vast differences in practices and teachings among the various schools of Buddhism. But, really, that’s like being surprised to discover that Catholics and Baptists have different practices and beliefs, even though they’re all Christians. Because of the diversity within Buddhism, and also because I personally tend to have somewhat idiosyncratic views, you may find that the Buddhist places you visit have far different ideas about sexuality than what I am laying out in this book. I only really know Zen, myself, so that’s all I’m going to be addressing here. I don’t even claim that what I’m saying here goes for all, or even most, Zen people. And, just FYI, we Zen Buddhists tend to be so arrogant that we just call what we believe “Buddhism” without specifying the sect. I’ll be doing a little of that, too. Deal with it.

Also, I will use the word meditation from time to time to refer to zazen practice. I do this mainly to keep from repeating the same word over and over, as well as to remind those who may not be familiar with the word zazen that I am talking about a practice that most people consider a form of meditation.

In these cases I’m using the word meditation as a blanket term to cover sitting still in that way that, y’know, like, meditators do and stuff. I’m sorry to get all vague and “teenage” on you here, but let me unpack this a bit, and maybe you’ll understand why. According to the dictionary function on the word-processing program I’m using, meditation means “emptying the mind of thoughts, or concentration of the mind on just one thing, in order to aid mental or spiritual development, contemplation or relaxation.” That’s not zazen — which the same dictionary function tells me is “a form of meditation in Zen, practiced sitting in a prescribed position.” Actually, that’s a good definition and a good use of the word meditation, just as a rather neutral term for a type of familiar activity.

But most forms of meditation are pretty much what the folks at the software company think they are — methods for emptying the mind or developing concentration aimed at some kind of spiritual goal. Zazen, on the other hand, looks like meditation in that you sit up straight and cross-legged staring at a wall. But there is no goal to the practice. You’re not trying to empty your mind of thoughts or concentrate on anything. You allow thought to proceed as it needs to without deliberately adding to the stew. This is, of course, far easier said than done.

Zazen is not a means to any end. It’s not a method to get spiritual enlightenment or anything else. It just is what it is. This is a very tricky subject. So rather than attempting to comprehensively describe what zazen actually is right here, I will do so piecemeal throughout the book. I’ve also added an appendix to try and explain it more succinctly.

At any rate, the foregoing is just a heads-up for you, so we’re clear on a couple of things. But let’s get started with the discussion about sex. That’s what you paid for, after all!

In April 2009 I was giving a talk at a place called Casa Del Popolo in Montreal. I had given a talk there once before, about four years earlier. That one was kind of a tense gig. And a weird one. I’d never been there before, and I’d been told the place was a coffeehouse. But when I got there, the audience was drinking beer and wine and smoking cigarettes. This, I gathered, was normal for coffeehouses in Montreal. Mais sacré bleu! I had never spoken about Zen in a place where people were getting drunk. I wasn’t sure what kind of reaction I’d get in a place like this.

One guy in the back seemed angry about some of the things I said. From up on stage I could see him getting agitated as I spoke. When I opened the talk up to Q & A he was the first to raise his hand. He said, “Are you saying that there’s no difference between truth and what is true?” He seemed pretty pissed off about this. But I couldn’t quite get the question. This made him even angrier. I thought he was going to rush the stage and slug me.

But he didn’t. I answered as best I could — I think I said something about how there is no distinction made in Zen philosophy between Big Ultimate Truth and the small things that are true and factual right now — and I moved on to the next question. After the show the guy lingered, which worried me. But we just chatted for a bit. I got his email address. We emailed back and forth for a while, and then I stopped hearing from him.

But a lot of people who came to the talk in April remembered the guy and the incident at that talk all those years ago. They kept saying stuff to me like, “I wonder if that guy is going to be there again?” I was a little concerned myself. I didn’t know if he was a known psycho or something.

Anyway, the event went okay this time. But there was a guy standing by the door with a slightly ornery look in his eye. He looked a little like the guy from a few years ago. Maybe he was the guy. Sure enough, when the Q & A started he was one of the first to raise his hand.

“Are Buddhists allowed to jack off?” he said.

“They’re encouraged to!” I replied.

It was a weird question, and I’ll get to my full answer in a second. But it was that question, among other things, that inspired me to write a book about Buddhism and sex. Because when I answered that question, I ended up doing what every book I’d seen that addressed the subject of Buddhism and sex did. I regurgitated the history of Buddhist monastic rules regarding sex.

The history of sex in Buddhism in a nutshell goes something like this. The earliest monastic Buddhists were strictly celibate. Buddhists in those days were not allowed to jack off, much less have sex with any person, animal, or celestial being — this last one was something they considered a real possibility, so it had to be addressed. When Buddhism reached Tibet things changed drastically, to the point where a certain sect began to use sex as a kind of meditation. Then when Buddhism got to China, things became even a bit more varied. Most Chinese monasteries favored celibacy, but there were numerous notable exceptions. Later on, when Buddhism migrated to Japan, the government declared that Buddhist monks could be legally married. Then Buddhism migrated to Europe and America, and everything went crazy.

Or maybe it didn’t. Maybe we’re finally coming to terms with something those other folks never really dealt with. The dude’s question is significant and concerns me and, I assume, you as well. As I said, there are better books to read if you want to know the history of how Buddhism has dealt with sex. But I don’t know of any books that address the question of how contemporary Buddhists deal with it.

In trying to come to terms with the true Buddhist way of sexuality, I’m much more interested in how Western Buddhists of the twenty-first century approach sex than in what the ancients did. This might strike some readers as odd. We’re used to the idea that the best way to understand what a religion really stipulates about some subject is to go back to its earliest texts and discover what the founders of the religion in question said about it. If we want to know the proper Christian attitude toward sex, we consult the Bible, particularly the words of Christ himself. If we want to know how a good Muslim should deal with sex, we just open up the Qu’ran and see what Muhammad had to say on the subject. So if we want to know how Buddhists should view matters of sexual interaction, the best way would be to find out what Buddha himself had to say, right?

Well, no, actually. Buddha himself said in the Kalama Sutra,

Rely not on the teacher, but on the teaching. Rely not on the words of the teaching, but on the spirit of the words. Rely not on theory, but on experience. Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. Do not believe anything because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything because it is written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and the benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it.

Thus Buddha himself left us with completely different criteria for determining what is and what is not real Buddhism from those of any religion. If we accept Buddha’s words about his philosophy, it obviously won’t do to just look at history, even the most ancient strata. It also won’t do to accept at face value what has been said by great Buddhist teachers, or even by lousy Buddhist teachers like me.

If we want to know how to behave adequately and morally in terms of sex we can’t rely on solutions provided for other cultures and other times.

The specific matter of whether Buddhists were allowed to jack off was actually very important to me when I first started this Zen thing. I was a freshman in college and dating a woman who described herself as a born-again Christian. It’s a very long story. Don’t ask. Anyhow, she had strong opinions about pretty much everything, including masturbation. She didn’t necessarily think of it as sinful, though that was probably in the back of her mind. But she did think it was a form of cheating.

Her opinion was based on the famous quote from the Bible that to lust in your heart is the same as committing adultery. As far as I was concerned, even though I didn’t really believe in God in the sense of believing in a gigantic white man on a throne up in heaven who judges our actions, I still thought that maybe somewhere out there was a cosmic scale by which morality was measured. What I mean by this is that I thought maybe there was some absolute measure of right and wrong action, and I supposed that the Bible might possibly be a source of information about that absolute scale of right and wrong. So maybe masturbation was the same as sexual infidelity.

My parents, as far as I know, were the very model of sexual fidelity. They’d been together since high school and stayed together right up until my mom died in 2007. If they ever cheated on each other, I did not know and do not need or even want to know. But in all the time they were together I never even heard a rumor that either one was unfaithful. So the idea of sexual fidelity was very important to me. If the Bible was right, then I was in big trouble! But then I started to wonder: What if there were other sources of information about what was right and what was wrong?

I was attracted to Buddhism for a whole lot of reasons. One of the things I hoped to find was some way of determining the real nature and content of this absolute scale of right and wrong that I believed might exist.

I discovered that the question of what is and is not acceptable sexually in Buddhism is actually a small part of a much bigger matter. It’s about morality, what Buddhists call “right action.” In Western culture, many of our questions about moral action involve sex. We Western people tend to take for granted that our decisions about sexual action are all rather weighty moral matters. We believe this to such a degree that we even question whether or not even our thoughts about sex are moral issues.

But in Asian cultures traditionally far less attention has been paid to sex as a matter of morality. Which is not to say it’s all free love and orgies over there. But the Asian attitude toward sex has always been much freer — or at least lighter — than the Western one. Buddhism, being an Asian import, has a relationship to sex that is completely unlike the ones found in Christianity, Judaism, or Islam.

The key aspect that makes the Buddhist attitude toward sex utterly different is that the concept of sin does not exist in Buddhism. I will be saying this again and again in this book, to the point where you might get fed up with hearing it. But it really is the key issue.

As Westerners, our belief in sin is so deep that we tend to think of it as a real and substantial thing, even if we are not devoutly religious. Even if we don’t necessarily believe in sin ourselves, the belief in sin is so deeply ingrained in our culture that we cannot hope to escape it. Our belief in sin runs so deep that even when we learn that Buddhism does not have this concept, we try to look for it anyway. It’s not that we forget what we’ve been told. It’s just that we take it so much for granted that sin actually exists that we keep returning to the same idea over and over without meaning to.

I say this because I do it myself, and it’s weird that I should since I was raised pretty much without religion. My family wasn’t anti-religious or atheistic. They just didn’t really give a crap one way or the other. I was raised to believe that it was up to me to believe or not believe whatever I wanted. I had no religious indoctrination or training at all when I was a child. So when I see that even I react to a lot of what I find in Buddhism with a very deep belief in the real existence of sin, I can only imagine what people from more religious backgrounds have to struggle with.

Furthermore, in Western culture we’ve been steeped in the religious view that sex itself is a sin. Whether it’s good sex or bad, consensual or nonconsensual, within the bonds of holy matrimony or outside it — what they used to call “in sin” — the act of sex itself is seen as a sinful activity. It’s hard to know just why this is. As far as I’m aware the Bible doesn’t call sex in and of itself a sin.

It doesn’t really matter how we got the idea as a culture that sex is sinful. Maybe we got it from the fact that lust is called sinful in the Bible, and it’s difficult to have sex without at least a little bit of lust. At least, I’ve never managed it! What really matters is that most of us in this culture have the belief, however deeply buried it may be, that sex = sin.

But getting back to the preliminary stuff I wanted to say before we dig into these questions, I also have to let you know that even if you searched the entire world you could not possibly find anyone less qualified than me to write a book about Buddhism and sex.

The image that most people have of the ideal Buddhist master in regards to sex is that of a person so enlightened and self-controlled that thoughts of sex rarely arise in his* chaste and unsullied mind. On those rare occasions when such thoughts do arise, he redirects his spiritual sight to more lofty concerns, and the impure impulses pass away like an erection at 4:00 a.m. when you channel-surf from a phone sex ad to a commercial for “Sweatin’ to the Oldies.”**

That’s not me. At all.

At heart I’m kind of a horndog. This may be one reason why Gene Simmons of KISS has always been kind of a hero to me. He’s far less of a hero to me now than he was when I was a teenager, but I still like him. Gene was a rock star who did not smoke, drink, or do drugs, activities that hold no interest for me either. But Gene was, and by all accounts remains to this day, a sex maniac. While lead guitarist Ace Frehley and drummer Peter Criss destroyed their minds and bodies with booze and pharmaceuticals, Gene indulged instead in nookie, racking up a reported four thousand sexual conquests of various shapes and sizes. Apparently he would fuck anything with two holes. One of Gene’s band mates said of him, “You’ve heard of the Beast Master? Gene is the Beast Fucker!”

This I could relate to. It’s exactly how I imagine I’d have been, had any of my rock bands become successful — though I’d like to believe I would have been a bit more selective and avoided the beasts. If I’d had a chance for a life of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, I would have indulged heavily in the sex — and in the rock and roll, of course. But I doubt I’d ever have been a druggie.

Sex has always been my main vice, my main temptation. I’ve kept it in check by getting involved in long-term monogamous relationships in which my sex drive could be reined in. But even so I’ve lived my life bass-ackward. I spent my twenties and thirties in domesticated monogamy, and it’s only been since I entered my forties that I found myself cut loose, not by my own choice,* and free to indulge sexually the way most people get over doing by the time they are out of their twenties.

So what you will be reading, if you choose to keep reading this book, will be the product of my own struggle to come to terms with sex and how to deal with it as a Buddhist teacher.

Sex and spirituality are odd bedfellows. Most spiritual practices are not very sex positive. And a few are a bit too sex positive, to the point of being a little creepy. Or a lot creepy.

But Buddhism is not a form of spirituality. This may surprise you since you probably found this book in the spirituality section of your local Book Barn. So maybe we should get that out of the way right now.

The history of philosophy throughout the world has been a struggle between two basic fundamental systems — idealism and materialism. Spirituality is a kind of idealism. It takes the view that the spiritual world, the world of ideas, imagination, and mental formations, is the true reality. Matter is regarded as secondary at best or sometimes even as nonexistent. We are spirits trapped inside bodies made of gross matter — and some bodies are a lot grosser than others — and the way to happiness, according to the idealists, is to get free of this material world and its miseries.

In many Eastern philosophies we are told, “I am not this body. I am the spiritual soul within.” These days, what people in the West often regard as “Buddhism” is really just a mash-up of a couple dozen Eastern philosophical traditions. So people often think this is the Buddhist belief as well. But the idea that we are souls trapped in bodies is not at all a Buddhist viewpoint.

Materialists, on the other hand, see matter as primary and spirit either as nonexistent or, at least, as negligible. What we perceive as our soul, we are told, is only the workings of a highly complex biological machine. We’re all just animals. The Marxists tried to find a rational way to deal with this by distributing material wealth fairly so that everyone could have the best chance at a good life. Or at least that’s what they said they were doing! The more radical materialists assert that the only way to be happy is to get as much money, sex, and power as possible for yourself and screw the other guy. There is no soul. There is no afterlife. There is no God. There is no reason to be moral, they say, because the material world does not operate according to those terms.

Buddha explored both these ideas and found them lacking. He was born a prince and spent the first part of his life dedicated to the practical study of materialism. He had everything he could possibly want — money, hot babes, power. We’ll get into the hot babes bit a little deeper* later on in the book.

But these things didn’t make him happy. So he set off in the opposite direction to see if happiness could be found there. He dedicated himself to various spiritual practices, such as fasting, and achieved their highest goals. He got a massive spiritual high, but in the process he nearly destroyed his body. That wasn’t what he wanted either. It wasn’t until he rejected both extremes and found the Middle Way that he began to teach the philosophy that now bears his name.

Buddhism starts from the basic premise that neither materialism nor idealism is correct. We are not immaterial spirits trapped in material bodies, nor are we mere permutations of essentially dead matter who only imagine we have a spiritual side. The Heart Sutra says, “Form is Emptiness, Emptiness is Form.” In other words, matter is the immaterial, the immaterial is matter. With apologies to Sting, we are not spirits in the material world. Rather, the experiential, internal, subjective, spiritual side of our day-to-day existence and the hard, external, objective, material world we inhabit are manifestations of one underlying reality that is neither spirit nor matter.

This is a very radical idea. Even today, 2,500 years after Siddhartha Gotama first put forth this notion, few people can accept it. Even those who call themselves Buddhists all too often believe that Buddhism is a form of spirituality.

While it’s not spirituality, Buddhism is not materialism either. Buddhism is realism. There’s a tendency for contemporary people to assume that realism is the same as materialism. When they use the word reality it most often refers to the material world as explained to us by science. But that’s not how Buddhists think of “reality.” The materialistic point of view is also just a concept. It is not reality, and it is not realism.

Now, matter itself is obviously real. If you have any doubts just drop a big rock on your foot to check. But the trouble is that our understanding of matter may not be accurate. Most of us believe that matter exists first, and because of the existence of matter sense stimulation occurs. Both idealists and materialists tend to conceive of it this way. The book in front of you is made of matter and it’s real. So is your forehead. If you smack your forehead real hard with the book, your head will hurt. The subjective experience of pain is the result of the objective collision of material forehead with material book.

Buddhist philosophers like Dogen, Nagarjuna, and Buddha himself turn this around and place sense stimulation first. They say that it is because our senses are stimulated in certain ways that we then assume matter exists. It is a completely different way of conceptualizing the world from what we’re used to.

Science happens to be a very good way to look at the material side of reality, so we need to accept science.* But Dogen, the thirteenth-century Buddhist monk who founded the school of Buddhism in which I study and practice, said that the universe in all directions is just a tiny fragment of reality.

That doesn’t mean that the material world is here and that somewhere out in the vastness of space is another even bigger universe made of something else. Dogen was talking about our day-to-day experience. The material component of our experience forms just one small part of our reality.

Furthermore, we never experience mind separate from body, and vice versa. The idea that one side is true, while the other is false, doesn’t fit our real experience.

We constantly swing back and forth between materialism and idealism. When materialism doesn’t satisfy, we try idealism. When idealism lets us down, we swing back to materialism. As a culture we can see this happening right now. A century ago it seemed like materialism might one day solve all of humankind’s problems. But in spite of the fact that most of the poorest among us enjoy wealth and comfort our ancestors couldn’t have dreamed of, materialism has failed to fulfill many of our most basic needs. Science created the flush toilet and sliced bread, but it also created the atomic bomb and a host of other horrors. So, as a culture, we have started to drift back toward spirituality in the hopes that a more spiritual approach might solve our troubles and bring us the fulfillment we seek. What we’ve forgotten is that we pursued spirituality for thousands of years before we got started on the materialism kick. Spirituality already let us down. It didn’t fulfill our basic needs and wants. That’s why we became so materialistic in the first place.

A lot of people look to Buddhism as a spiritual answer to their materialistic woes. But if Buddhism is just another form of spirituality, it’s as worthless as any other religion. We need something different. And Buddhism is something very, very different.

Every religion, philosophy, addiction, and any other method for dealing with what life throws at us that I’ve ever encountered says, “You feel unfulfilled? Okay. Try this. It will fulfill you.” Materialism works for a time. But after you buy something the thrill of buying it vanishes, and you want to buy something else. Spirituality can give you a great big high. But there’s always a comedown.

Buddhism doesn’t promise to fulfill our desires. Instead it says, “You feel unfulfilled? That’s okay. That’s normal. Everybody feels unfulfilled. You will always feel unfulfilled. There is no problem with feeling unfulfilled. In fact, if you learn to see it the right way, that very lack of fulfillment is the greatest thing you can ever experience.” This is the realistic outlook.

Because of this notion that the truth is neither spirit nor matter, when we get into sexuality, Buddhism does not proceed from the same standpoint that spiritual religions do. Much of the hatred and fear of sexuality found in religions stems from the idea that sex is a thing of the body and that the body must be denied so that the spirit may be elevated. In Buddhism there is no notion that the body is made of inferior matter while the spirit flies free within.

My teacher Gudo Nishijima uses the phrase dimensionally different to talk about the way Buddhism is radically unlike other religions. By “dimensionally different” he means that the Buddhist view is so unlike the religious view that comparisons become almost absurd. It’s as if they exist in different dimensions. This is certainly true of the Buddhist take on sexuality.

One of the most important aspects of Buddhist practice is the idea of moderation, the Middle Way. While most of us can usually see the logic of practicing moderation in most things, we tend to put sex into a special category where extreme reactions of all kinds are not only acceptable but almost inevitable. We’re either way too hung up on getting sex or way too hung up on avoiding it. Either our sex drive is too great and we try desperately to control it, or it’s too little and we start popping Viagra or taking hormones. What’s the deal with that stuff anyway? Does everyone’s sex life now have to mea-sure up to some kind of Penthouse Letters-inspired fantasy? They make that stuff up, you know…

On the other side, religions tend to advocate various ideals of sexual purity. And this often leads to trouble. Whether it’s Roman Catholic priests fondling choirboys or Indian gurus bedding movie stars, it seems like the religious world is rocked every couple of years by some kind of sex scandal. The Buddhist world has had a few sex scandals, too, including some involving a few well-known American Zen masters.

It’s easy to see why this is so. Religious leaders are always presented as something better than ordinary people. True believers see these people as manifestations of the divine, as the living embodiment of some kind of ideal.

But what are ideals, really? They don’t actually exist outside our brains. When we project our expectations about what a divine being ought to be onto real people, what else can we hope for besides disappointment? Of course, it doesn’t help matters that so many people are perfectly willing to be thought of as manifestations of the divine. Still, the worshippers of such people deserve as much blame for their disappointment as do those whom they worship. Without any followers, people who think they’re God’s messengers are just delusional. But when they’ve got crowds of worshippers around them, look out!

Ideals are always matters of mind. And in the pure world of mind, unsullied as it is by messy things like bodies with wee-wees and pee-pees attached, there is no sex. So divine beings should not boink. When we discover that the folks we considered divine are in fact boinking away like mad, our dreams are shattered. In fact, it is precisely because these people are trying to live up to an impossible ideal that they so often turn sex crazy. It’s an unbalanced way to live, and nature has a way of balancing things out by tipping the scales in the opposite direction. I’m not saying that celibacy and chastity are in and of themselves impossible. But it isn’t just celibacy or chastity we expect from our representatives of the divine, is it? It’s purity.

And that’s where we get into real trouble. Because purity is very hard to pin down. What is it, anyway? “Purebred” dogs and horses do not exist in nature. They are artificially bred by human beings. “Pure” water is water filtered by human-made machines. So what about pure desires? Could all purity be a human concept, never to be found in nature?

People who are “into Zen” often tend to misunderstand the point of Buddhism to be the destruction of all desire, including the desire to get one’s rocks off. But this religious attitude toward sexual purity just replaces society’s extreme views on the matter with another set of equally extreme views. The real problem — the fact that we permit ourselves to act so extremely with regard to anything at all — remains unaddressed. To view sex as a vile act that the pure of heart dare not even dream of is in its own way just as unbalanced as spending all your time, energy, and cash trying to get some hot man-meat or some tender yoni.*

To practice the Middle Way means applying that view to all areas of your life, without exception. You can’t establish real balance if you hold certain areas of experience apart and say it’s okay to go to extremes as long as it has to do with sex, or with skeeball, or with whatever it is you’re obsessed with. Constantly moving from one extreme to the other is what got your brain and body into the mess they’re in right now. How can you expect to get at the root cause of your troubles by doing the very thing that caused the troubles in the first place?

Not being a total sex freak doesn’t mean you have to swing the completely opposite direction and try to live your life as a sexless robot. Deal with the sexual desires you have in the most reasonable way you can.

When you’re jacking off, just jack off. When you’re not, just don’t.

© 2010 by Brad Warner. Printed with permission of New World Library, Novato, CA