This article originally appeared on Starhawk.org.

I've been meaning to write this essay for three years, since I went down to New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to volunteer with a grassroots organization called Common Ground Relief. I went to New Orleans because for decades I've been part of groups holding a few key beliefs, among them, that this current system is unsustainable and will eventually come crashing down, and the other – that small scale, directly democratic grassroots organizing is the most empowering and effective way to take action. I wanted to see what it was like in a place where the crash had come, and to see if our grassroots, do-it-yourself mode of organizing could work in that situation.

Now, with the Gulf Coast battered by a new round of storms, Wall Street deconstructing and capitalism in meltdown mode, that prediction is coming true. It seems a good time to review those lessons.

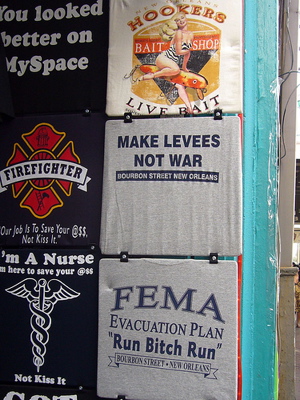

In New Orleans, the crash had come. Not just the devastation left by the storm – every major system that was supposed to offer protection, succor or relief had failed. Starting with the faulty levees built by the Army Corps of Engineers, moving on to an evacuation plan that was no plan at all for those without means, to completely inadequate shelter facilities for those who remained, to disorganized and punitive responses for those who survived, nothing official was working.

When I arrived, a month after the hurricane, the only systems that were functioning were the decentralized, autonomous relief efforts – groups like Food Not Bombs, who fed thousands of people, Burners Without Borders, and the group I worked with, Common Ground Relief. Common Ground Relief was started by a local organizer, Malik Rahim, who lived in Algiers, a neighborhood that had not flooded. He sent out a call that made its way into activist circles.

And people responded. Nurses, doctors and street medics who had honed their skills setting up emergency clinics for street actions went down and set up a functioning clinic long before the Red Cross arrived. Others helped set up distribution for relief supplies, and later, as residents began to filter back, organized groups of volunteers to gut houses contaminated with toxic black mold and to offer other forms of service. I worked on a bioremediation project, using natural methods to decontaminate soil.

The experienced deepened my commitment to decentralized, grassroots organizing. Our ability to move swiftly, without being hampered by red tape, to respond to immediate need and to call on thousands of people to volunteer their time, efforts and money was impressive.

But I also saw our limitations. I remember sitting in one early meeting where we were discussing whether to send supplies across the river to the main part of town, still without power, or out to Houma in the bayou country, or to focus where we were. "What about Mississippi?" someone said. "I hear there's no relief in Biloxi at all!" The discussion spun down a vortex of overwhelming need, and I remember thinking, "There should be someone or something who could send a team into every county and parish, assess the need, set up distribution…"and then…"There is an agency that's supposed to do that. It's called FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or failing that, the National Guard."

The National Guard was partly in Iraq, partly in Florida moving military equipment out of the way of the storm. While the military had searched every house in the city for bodies in the aftermath of the flood, they were providing more harassment than relief to those who remained. FEMA was under the control of a Bush political appointee who has become a famous symbol of utter mismanagement. And I couldn't help thinking, "There are people dead today who would still be alive if we had had somebody even minimally competent in charge."

Our grassroots efforts were effective, but they couldn't begin to match the enormous need. Eventually, Common Ground Relief had centers in several different neighborhoods in New Orleans, and along with many other relief efforts, drew on thousands of volunteers who came down over the next year. College students came down on breaks, communities sent down convoys of supplies and helpers, but there was no way we could respond on the scale of the disaster.

Our volunteer efforts were also difficult to sustain over time. While many, many people made personal sacrifices in order to come, and some stayed for a year or more doing unpaid and extremely difficult work, not many people could afford to do that. Efforts like our bioremediation project suffered from lack of consistency. When a person who had enthusiasm for it was there, it flourished. When they left, it died.

Volunteer efforts also depend on people getting along well together. Direct democracy means people make decisions together, and that can be tremendously empowering or tremendously frustrating. Stress, trauma and overwhelming need do not further good group process. Common Ground's efforts often felt the strain of interpersonal conflicts, which also drained energy and enthusiasm from volunteers.

I came away from the experience with profoundly mixed feelings. On the one hand, I see even more strongly the power of positive, creative direct action – that is, directly solving our own problems, organizing to provide for needs and to exemplify solutions, and doing it in groups where every person involved has a say in decisions. I feel called to help plant the seeds of that kind of organizing in every neighborhood, town and bioregion of the land, and to help further refine our skills in making decisions and handling conflicts.

But I also see the need for big systems. There are problems that need to be addressed on a massive scale, and we face some crucial ones at this moment in history. While my long-term vision is a world of empowered, decentralized communities in charge of their own destinies, there's a short term problem we desperately need to address: completely transforming our technology, our energy infrastructure, our economy, our food, manufacturing and transportation systems to a zero carbon basis, and doing it in a way that furthers social justice.

I call this a short term problem because we need to begin this transition now, not in some distant, utopian future, not even in fifty years or fifteen or ten. Jim Hansen, the world's leading climate change scientist, says we are already past the tipping point for irreversible, runaway climate change. That means potentially billions of deaths, from drought, from thirst, from increased and frequent storms like Katrina and like the hurricanes currently battering the Caribbean and the Gulf Coast, the potential rise of sea levels, billions more left homeless refugees, major extinctions and huge losses of biodiversity. Trust me, we don't want to go there if we don't have to.

And we don't have to. We have the technology and knowledge we need to make the shift – possibly with less personal sacrifice than we think. You don't have to trust me on this, check out the resources at the end of this post and read the folks who have crunched the numbers for us.

But we do need to make the shift on the big scale as well as the small. Changing our individual lightbulbs won't do it. Organizing our own communities to plan and implement the transition will be a big step, but it won't be enough. We need massive investment in new infrastructure and major shifts in the policies that have subsidized the current fossil fuel economy along with the failed global casino economy. In short, we need intervention on the scale of government.

If we're going to have government, it should be well-run, honest, and accountable. Its police powers should be limited and it should serve as a way for us to pool our resources and address issues that are too big to solve individually. It should protect the weak from the strong, the poor from the rich, the honest from the greedy, and use its resources to help mitigate the suffering of individuals from the misfortunes of loss, disease and disaster which can afflict us all.

Instead, we've had eight years and more of the opposite – government that has increased police and military power at the expense of every nurturing function, inflated police power and undermined our freedoms, waged illegal wars, favored the rich over the poor and middle class and encouraged such unbridled greed that the whole system is now collapsing. Unfortunately, in such a crash those at the bottom get crushed under the most weight.

We have the Republicans chanting 'Drill, Baby Drill!" while blocking the extension of tax credits for solar, wind and renewables. If the question is, "Which candidate is more likely to lead us to a solar future", there's simply no contest.

Let me just say here that, in the circles I run in, the question is not, "Should I vote for Obama or McCain." The dilemma is "Should I bother to vote at all, when even Obama's policies are not nearly progressive enough. Won't he just sell out and betray us, like every other politician?"

Obama won't save us. His policies do fall short, for me, in many respects. But he is headed in the right direction, toward the future while McCain and Palin want to drag us back into a feudal, fossil-fueled, fundamentalist past.

If Obama did represent my position, on say, Palestine, he would be unelectable. Asking politicians to take unelectable positions is like asking ducks to sink. If we want those positions represented, we need to build popular support for them. And we need to make that support mean something in terms of votes, funds and volunteers.

On some issues, progressives have done that. The fact that Obama is running at all is a tribute to the civil rights organizing over decades. No, we haven't ended racism, but we've moved in my lifetime from being a country where Obama and I could not have drunk from the same water fountain in many states to a country where he can run for President. That is an extremely meaningful change, and his election will have a powerful, symbolic meaning that will shift the ground of racism in ways we cannot fully anticipate.

We've built powerful opposition to the War in Iraq. Or maybe, the war itself has done that for us. Obama is the candidate because of that opposition. Had Hillary Clinton opposed the war more strongly, she would most likely be the Democratic candidate. Nonetheless, her candidacy, and the fact that conservative Republican strategists turned to a woman to bolster their faltering campaign, are a tribute to the decades of feminist organizing that have changed our collective sense of what women's roles should be.

On other issues, like justice for Palestine, we have not yet shifted public opinion or built enough support for a truly progressive solution even to be on the table. Why not? In part, because for the last eight years trying to organize in this country has been like trying to walk to the left with a gale force wind pushing us to the right. We've done well even to hold our ground and make some small headway.

I don't think Obama will be our savior. But if he's elected, the wind will shift. The breeze will be at our backs, pushing us further and faster toward destinations we otherwise cannot reach.

If McCain wins, or steals the election, the right will claim a popular mandate that will propel their destructive programs onward. Progressive causes and movements will suffer.

I sometimes hear the argument that it has to get worse before it gets better, that people will become radicalized when it gets really awful. I've been hearing that since Nixon was elected in 'Sixty-eight, and I've yet to see it happen. It is already really awful, and we'll be lucky if we can persuade most of the people to simply not vote the architects of the awfulness back into power.

People do not become empowered by constantly having their powerlessness rubbed in their faces. In the United States, at least, where the worst possible thing you can be is a 'loser', people like to be on the winning side. Increased repression does not tend to make people more radical – if it did, we'd see our movements growing over the last eight years instead of shrinking. It tends to make people give up, or turn their energies toward smaller efforts where they feel they can make some impact. A McCain win would reward the machinery of lies and corruption and cement the power of the police state.

For Obama to win, and to assure that this election does not get stolen like the last two, he needs to win big. To have some hope of implementing progressive changes, he needs to have a supportive Congress and Senate win with him.

I hear arguments from some of my dear friends that voting doesn't matter, that it's not empowering or revolutionary. But for the vast majority of people in this country, elections are the only place where they interface with politics or attempt to exercise power, and if we sneer at that, we lose the chance to link together and open up broader channels for change. And for the kids I've worked with in the Bayview, who have never seen a flowing river and whose career options range from crack dealer to murder-for-hire, voting would be a big step upwards.

I'm a registered member of the Green Party. I vote Green often, and on a local level, I think the Green Party can have an enormous impact. I also love Cynthia McKinney, whose policies are much closer to those I hold dear. But I hold no illusions that she can win. A Green Party can provide a counterweight on the left to the many pulls to the center and the right that play on candidates. But I would prefer to see the Green Party concentrate on the local issues and candidates that can make a difference, rather than make a weak showing on the national front.

Policy is only one aspect of what we need in a President. A President must be able to garner the power and the backing to get policies enacted.

And on an energetic level, a President embodies a national mood, a zeitgeist, an energetic field. Obama has that magic charisma, that ability to inspire a mood of hope and optimism. In spite of all the attempts by both Clinton and the Republicans to diminish his appeal, he retains that great gift. In these times when so much of what ordinary people have depended on is crashing down around us, mood might actually be more important than specific points of policy. Because if we have no hope, if we spiral downwards into cynicism, despair and apathy, we will lose any power we might otherwise wield.

Obama may or may not be all we hope. But this election, we actually have a clear choice between candidates who represent very different approaches to the huge crises that we face. For the people who've lost their homes or pensions in the last months, for the people under fire in Iraq, for the companies struggling to start up solar or wind installations, for the millions without health insurance, for the billions of people around the world at risk from climate meltdown, the decision we make in the next weeks is crucial.

I will continue to work and organize and teach with the vision of a thousand, a million Common Ground-style organizations everywhere. I won't give up my vision of an ideal world of shared and decentralized power, and the bulk of my efforts will always go into envisioning that world, teaching the skills and understandings we need to bring it about, and agitating to make it happen.

But I'm also going to vote, and to encourage others to do so, to engage with this election, to register the disenfranchised, work in the swing states, volunteer to monitor to assure fair elections, and talk to your friends and neighbors.

And when I cast my ballot for President, it will be for Obama.

Footnote:

If you are looking for good, solid, number crunching around energy policy and the transition to a carbon-free society, check out:

Arjun Makhijani. Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy. Takoma Park, MD.

Institute for Energy and Environmental Research – www.ieer.org.

It's not sexy writing, but it's vital information, very technical and well researched. Makhijani was skeptical that the transition could be done economically, then did the research (funded by Helen Caldicott) and found that indeed we could.

Image by MadAboutCows, used courtesy of a Creative Commons license.