Many people know Larry Kirwan as the frontman for the groundbreaking New York City band, Black 47. Since its inception in 1989, Black 47 has never compromised in its mission to make people think about the effects of political oppression, most especially the type that the people of Ireland have felt from years of exploitation at the hands of the ruling crown in Britain.

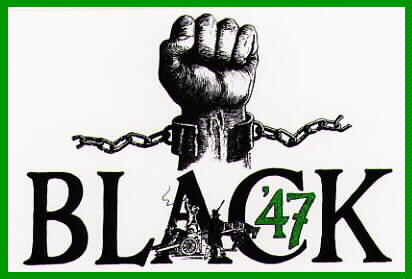

The name of the band itself is a reference to the Irish Potato Famine of 1847, when many Irish needed to flee their homeland because of the food shortages which were aggravated by British policies on the country.

Black 47 has maintaned a steady tour schedule over these nearly 20 years of existence. They have been a staple in New York City during these years, and play an annual set at B.B. Kings on Times Square every St. Patrick’s Day. One can also see and hear them at Connolly’s Pub every week when they are not on the road.

Larry Kirwan himself has been on the independent music scene of New York City since the 1980s. An Irish immigrant from the county Wexford, Larry was one of many inspired musicians and artists in NYC’s Lower East Side in the 1970s, and who played his music loud and without a care about who was listening.

He is an archetypal artist of New York. Someone who stayed true to his vision, and has done so without getting wrapped up in the various traps that have befallen others with his talent and fire.

Besides being a rock singer, Larry is also a graceful writer. His autobiography, Green Suede Shoes (Thunder’s Mouth Press) tells the story of an Irishman in New York that reminds people like me where we come from – and he does this with a tender human voice, leaving room for laughter amongst strong political actions and ekeing a living as an artist with conviction.

I see Larry as carrying the torch of a certain voice within Irish culture. A voice that calls for justice, while never forgetting to smile. A voice that reminds us to remember the struggles of the past, while also challenging us to conceive of a better future.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day, and enjoy.

Prop!: Larry, can you provide us with a bit of background information on the philosophical basis of your music, particularly you work with Black 47?

LK: Black 47 has been going for 19 years. It was formed in 1989, when Chris Byrne, a New York City cop who was very much involved with Irish Republican issues, and I met in a bar one night. It was kind of a fowl period in politics. Both of us were politically inclined. And we were just talking about how there were no political bands around at that time. Marley was dead, the Clash had broken up; I suppose Public Enemy was starting out roughly around that time, or were just getting going, but there seemed to be nothing really going on.

We formed basically to fill some dates that Chris’s band, which had just broken up that night. We were adamant right from the start that we were going to make political statements within the music. We weren’t quite sure how, because we had a gig coming in the next two weeks or so, but we were going to do it. I was doing most of the writing then, and I just went home and started to write.

So I had this rush of music come out of me. I went home and was churning out songs really fast because we were adamant also that we were going to go to the Irish working class bars, mainly because they paid, and we’d do the four sets a night that the regular bands were doing, but we would make these four sets as original as we could. So it was just this goal.

The songs also came out political. For one thing there was a lot going on in the Irish Republican world at that time. The Guildford Four, who were friends of ours, had just been released and were over here in New York. The Birmingham Six were released soon after that. So whenever groups would come over, we would be playing for them and they would be coming to our gigs.

The Joe Doherty extradition case was going on at the same time of the first two years that we had formed. Sinn Fein, for instance, were pairiahs at that point where they weren’t fashionable as they are now. There was this Irish Republican world in New York City that had no one singing about them. They were holding protests and holding functions, and we were the band. We were the ones who brought people to it, and in a certain sense brought people together from both the left wing and the Republican point of view. People who might not have got on together were coming to our gigs and meeting there, and realizing that they had a lot in common. It was just a great period in Irish-American life.

About what time period was that?

From the minute we formed – from in November 1989 I would say, and it went pretty much until Sinn Fein were brought in out of the cold in 1996, 97. It went on for that period, and it was more intense at first. As we got more popular, we were traveling around the country, there would be an Irish-American base there and within this base there would be Irish-American activists and they were the first ones who would come when we’d play.

We insisted that anyone who had a cause had to be allowed to set up their booths in whatever hall or whatever pub we were playing. It was just a thing we did. So there would be all sorts of movements represented there. There would be the Native American Movement mixed in with all sorts of Irish, Marxist, Republican stuff. Anything progressive was welcome. We didn’t care what it was as long as there was a progressive feel to them. We didn’t want any fascists or anything like that, although there was a number of them within these different groups. But our big thing was Self-Expression. That people come and make their point at the gigs. It was a great rush in Irish-America because a lot of the activists, activists are great they are out there working all the time, and so when we would come to town that was their big moment because we were their band. And we would bring the young people out.

And our idea was to take this folk hatred that a lot of young Irish-Americans in general had, this folk hatred towards Britain, and to fashion it into a political movement. Don’t just hate the British, find out what you can do to change things both in Ireland and the US for the better.

In speaking about this feeling of hatred felt by Irish-Americans towards Britain, to me it feels a bit manufactured at times. Like something expressed during a drunken rant on St. Patrick’s Day. I know that that is not always the case, but I have thought at times there’s been a lack of historical analysis of the situation and it becomes a stereotype of some sort. Like Irish people hate the British, and they drink a lot.

Well, that hatred is gone to a certain degree now, though a certain amount of it is still there. Back in 89, 90, 91 that feeling was prevalent throughout the whole country, if you look back through the history of it. A lot of people who are Irish-American – their parents, their grandparents going back 4 or 5 generations – all that they knew about it was that the British had basically thrown them out of their own country. And there was this hatred felt, and they didn’t know what it was. And we were intent on not educating them because you don’t want to be in a rock band and try to educate people, but to introduce them to people like James Conolly and Bobby Sands. And sow a seed in them, so that when they left the show they might go to a library and find out what it was about. Now they might go on Wikipedia and find out. Then we would come back the next year, and guys would come up to us and say, “I’ve learned all this stuff about James Connolly.” They would be more left-wing than we were. Sometimes they would go even further than we had gone, and we wouldn’t be extreme enough for them. They would go beyond us.

Our thing was to fashion this. And we had great succes at it because politicians began to see when Black 47 was in town, “I’m up for election, all the Irish are going to be there. I’ll go up and meet Black 47 and have my picture taken with them.”

But we refused to endorse anyone. We never endorsed any politician. We always felt that no matter which politician you go for, they will let you down. That is the art of politics, compromise. So we didn’t want to be that closely associated with them. We would get our picture taken with them, that was fine. Also, they had to have progressive views, otherwise they wouldn’t dream of coming out anyway. There was a lot of reactionary feeling in Irish circles, and we tended to bring that out into the open to a certain degree.

There is a real wide variety of views within the Irish community and in the ideological stances, so each person within it could find something in Black 47 that they liked. For instance, there would be guys who would be semi-racist talking to me, and I’m thinking why are you talking to be with this shit, do you think I’m like this?! But they would even see this or catch that. Then there were people with very left-wing points of view, and it was almost like a liberation for them to come out and give out there pamphlets, and feel good because we were singing about James Connolly or Bobby Sands.

Again it wasn’t to educate, it was just to introduce, and then let people get their own views. We weren’t telling them what to think. We were saying, “I think this, but you think whatever you like.” This is the show, and the show is going to be entertaining too. You are going to have your drinking and your partying songs with the political ones. One of the great things – and I never understood how it happened, because if I was trying to visualize it, I couldn’t see how it would – but organically, the drinking and the partying songs mixed real well with the political, and does to this day. There are people who come for one or the other or both, and it never seems to bother them very much. I mean some of the politics bothered the right-wing people, but even they would write to me and say, “Well, I don’t agree with your politics, but I had a great time.”

In Tom Hayden’s book Irish on the Inside he speaks about a cultural amnesia, where he finds deep significance in how traumatic the 1847 Potato Famine really was to the Irish – with the result being an almost wilfull forgetfulness about their own culture and soul. Do you find relevance in Hayden’s statement?

It’s been a while since I read Tom’s book. Tom of course had a very different background than I had. He grew up in Michigan, and his people didn’t speak about being Irish and everything. Whereas I came here from Ireland. In certain ways I would look at this broad scope of Irish Americans, some of them put me off at first with the green beer and the shamrocks and everything.

Yeah, Saint “Paddy’s” Day. Not to sound like a stickler, but it’s Saint Patrick’s Day. That Paddy thing has always irked me a bit. Anyway, please continue.

You know, I write an article every year about St. Patrick’s Day, saying that I’ve gotten used to it, because to a certain degree it’s just saying that “We’ve arrived, we’ve made it.” They’ve gotten off the boats and made a great country for themselves. So I forgive a lot of the green beer thing. It’s like to New Orleans for Mardi Gras, it’s a celebration. There are so many different types of Irish-Americans. They always get steroetyped as one type of person. I’ve met thousands and thousands.

There are those who, and I don’t meet them much, but I hear about them from their younger family members saying, “My grandmother or my grandfather woudn’t tell me anything about Ireland. They wanted to forget.” I totally understand that. Ireland was an unforgiving place to them. They basically had to leave it without a good education, without a job – they felt put down, they came here with a whole new life and they wanted to forget.

So in certain ways I feel for them, and I hear about them from their grandchildren who then say, “We want to remember. I would love that they were alive now, and I could ask them the questions I’d want to ask.” And that’s the one thing I’d advise anyone from whatever background, Irish or African or Eastern European; speak to the old people, find it out, because once they’re gone, it’s over.

I learned that early on, because I was raised by an old grandfather, who was born in 1880, and he was the youngest in his family. His father was 60 when he had him. So through him I was able to meet his father, figurativly speaking, who had actually grown up during the Irish Potato Famine and who knew what it was like. And I had been really blessed with that.

I was just always into history, and having this old man, who raised me, who wanted to talk. Basically, he had been on the wrong side of the civil war and lost. And was living in a town that wasn’t Republican, and had to keep quiet about everything, and he unloaded to me, this kid. I was just able to get a lot of stuff out of him. So when I read history books of that period, I’d have his voice and the voice of the historian who’s writing about it. There is a place in the middle where you can find truth. History books don’t always give you the right history.

You’re referring to the 1921 Civil War.

Yeah, and he was on the Republican side in Wexford and the town was very Free State. So I see Tom Hayden’s point of view, Irish-America in certain ways was very crunched together. When Black 47 came into it, we were at these shows, and people were drinking, and grandparents were coming along with grandchildren. That was one of the great things about the band, we brought generations together. And around the country it really works at these Irish festivals we play at. The older people will come along, who don’t even like the music that much, and they’ll say “He’s singing about James Connolly. And that’s the guy I was telling you about, always.” And they are able to relate to each other. That was the most gratifying thing in getting all these letters and emails from people saying, “You brought my family together. We learned together through the music.”

You were living in the Lower East Side in the late 70’s.

I lived down there until ’88. It was cheap, and it’s glorified now. Basically, I was the first Irish person on Avenue A, ha ha. One of the few white people. There were white people there, but not many. Drugs were everywhere – but it was a vibrant scene. Vibrant because you didn’t have to work. You could get a couple of gigs a week. Get an apartment for $150 a month. So you had time, time to hang out. Before me and you were talking about when the country changed – what did you call it?

From Welfare State to Real Estate.

Yeah, or dream state to real estate. It was up until the end of ’82 when I noticed it. And how I noticed it first was in people saying, “I’ve been working so hard. I’ve been up working all night.” Whereas we never thought about working. You wrote songs and what have you, but you were up partying all night. And then you had so much time. And then all of a sudden, when Reagan got in and it became cool to be a yuppie, that’s when things changed.

Up until then nobody really thought about working. Working was something you did to have enough money to pay your rent, and to party. It was almost a sea change, in that nobody had to work too much. And now people were working because they wanted to work. Even in the art world you started seeing Art Yuppies. And then MTV came in at that point. MTV really changed music for the worse.

Growing up in the 80’s, MTV was how I got exposed to different types of music. Today they don’t even have videos anymore. I find it interesting to hear your perspective on it, because you are saying from the jump that MTV had a toxifying element for music and art. How so?

Well, I enjoyed it at first, but then the record companies got complete control of it. Thankfully that control is ending now. But during that time, up until MTV came about, it was all about the music and getting it down to a record. For the first year of MTV there was an explosion of everyone wanting to make some video art. Then the people from the ad world got involved and videos began to cost $50,000 to $100,000.

Basically you had to be with a major record company or have a huge amount of money to have this adjunct, which was the video, to sell your records. So now you had a record that was costing $50,000 to a $100,000 and also a video which would cost the same. To actually pull these two things off and get on MTV, which would help you sell a lot of records, you had to be with a major record label or have a huge amount of money. And it cut out everybody underneath it, so you had to go through the system.

We were on MTV eventually, so I’m speaking from experience, but I saw MTV as being that toxic element. And it has also dumbed down America. At first it wasn’t meant to be dumb, but flashy. I knew some of the people who were running it who were very intelligent people. But the whole idea was about making people dumb, and I violently objected to that. Because that’s what led people to be dumb enough to allow Bush to go to war in Iraq.

It’s kind of a long stretch from MTV to that, but it’s this pounding away of televison creating a seperate reality, so that people think the reality on televison is more real than the reality of being on the streets.

1981. Bob Marley, Bobby Sands, and John Lennon all pass away.

I’m writing a book about that period called Rocking the Bronx. It’s strange for me to go back into it because it feels like a different reality.

On the positive side, did you see any birth or seedling of a shift going on in Irleand when Bobby Sands and the other hunger strikers died up in Long Kesh?

Eventually I would, but the surge was stronger over here in Irish-America. The Hunger Strikes radicalized a lot of people who wouldn’t necassarily consider themselves Republican. It was just confronting what Maggie Thacther’s way was. It wasn’t that she disliked Irish people, she disliked people of a certain nature, whether Irish or English. Many of my English friends were a lot more Anti-Thatcher than my Irish friends. It was definetely a good change here.

In Ireland, it did change things for the better, but there was already a fatigue set in because of the sheer amount of violence that had gone on. People were tired. Yeats said, “Much hatred, little room,” and that’s a great quote especially about Northen Ireland. The hatred level was just so intense there.

Were you aware of the Irish Northern Aid up in the Bronx? My parents were heavily involved with them around the time of the Hunger Strikers. What were your impressions of Northern Aid?

Well, I thought there were many good people in it. We, Black 47, although we knew many involved in it, decided not to be involved in it. We decided that it was better to be an independent voice. Besides which, we were being hammered by the British media as being the musical wing of the IRA. So even though we knew a lot of the people, we were friendly with them and sympathetic with them in a lot of cases, we just had to keep our distance from the actual orgainaztion and the sending money back to the prisoner families and everything like that.

We just felt that it was a wiser thing to do. I thought it was a good organization. I presume a lot of money was going back to the IRA and Sinn Fein. Who knows? I didn’t ask. It was going to prisoners, it was going all over the place I would imagine. They were good people, they had the right intentions, and it was fine by me.

Awareness is the greatest thing to me. That poeple were becoming aware was really important. There was a broad spectrum of people here, especially with Bobby Sands and Joe Doherty’s campaigns, because people realized that this was wrong. It doesn’t matter what your ideological stripe was. If it’s wrong, it’s wrong. One of the regrets that I have is now that the conflict is over, people have seperated and gone their own ways again. It’s a lot easier for people to be against something than for people to be for something. Like a number of my friends won’t speak to each other who are on very different wings of Republicanism.

Yeah, that seems to be something that haunts Republicanism, the sectarianism, the constant bifurification and splitting into separate camps.

It’s kind of inevitable in Irish situations. It’s just one of those things. I’ve stayed friendly with all of them, because we were all comrades at one point. Personally, I just don’t think if you are friends and comrades with someone, if you disagree with someone, then why ostrasize them? I’ve always believed that we are stronger together.

Do you remember anything about the Fortworth Five?

I think so, there were so many Four’s and Five’s in those days. Haha.

Right. My mother was brought before a judge down in Texas. She was one of nine people who were subpoeanead down there on some charges, but never indicted. However five people were, and they were later called The Fortworth Five. Up in the Bronx, though, my Mom worked for Paul O’Dwyer.

Paul was a great man. He was an amazing character. It’s a real pity that younger people didn’t get to see him work. Back in those days, Sinn Fein and any type of Republicanism wasn’t sexy, wasn’t fashionable.

It was great to see someone like Paul O’Dwyer, because he was like a chieftan. He’d come in a room and be strong and powerful, and was so aware of himself, not in any fashionable way, and he would give people heart. He would make people feel good about themselves by just him walking into a room. He was a remarkable person. I was always very struck by him each time I saw him. He was that way every time. And his brother was the mayor of New York City.

Yeah, the judge called my Mom the most dangerous woman in America next to Angela Davis. I think he was more fond of his own little quotes than anything else.

Ahaha, that’s funny. Angela Davis used to be on the scene. She used to be at Irish protests. I’m pretty sure she came to the Bobby Sands demonstrations. I knew her more from the Lower Eat Side, but I’m sure she was at some Irish events.

Yeah, I was talking to an older Black Panther cat at this past year’s Zulu Nation anniversary. We were talking about the Irish political movements, and he said that they worked with them sometimes, but they had to be careful becuase there were also a lot of Irish who were cops. That’s a very interesting part of the Irish in America. That’s why I find it interesting that Chris was a cop, yet he also had these very strong political views. It’s a funny friction.

And it’s a real friction. A lot of cops were that way. It was a striking time. Cops often get misportryed too. There were a lot of radical cops around in those days. I’m not sure what it is like now. I used to meet more cops in those days through Chris. I used to think of them as a monolithic force, but they weren’t. They were guys who were into the wildest music, and I would think, “You’re into that?” Guys who were into Hip-Hop, etc. There were a lot of cops who were politically left too.

You have mentioned somewhere that Afrika Bambaataa is an influence. Can you talk about that?

Well, we were hearing him and lots of other Hip-Hop. I remember hearing “The Message” first. People would be playing it around Washington Square Park through their boomboxes. There was this feeling of change. KRS was big too. Because they were political. There was this feeling of political solidarity. I mean, I enjoy Jeezy and Lil’ Wayne because my kids play them, and I recognize the word play and some of the funny things said, but Chuck D and people like him were a big influence on us becuase he was a serious guy who had an agenda, and KRS was the same thing. They were sticking up for their people. They had a really good influence on the youth around them, and that was important for me.

To Black 47 it is important to pass on a political message. Not to tell people what to think, but telling them to think. Because each generation has its own issues, but if the ones coming before them doesn’t give them sign posts, it takes them so much longer to find themselves.

I grew up in a real political environment in Ireland. Politics was everywhere. I mean there was a civil war, and those who fought in it were still around. And guys who were shooting at each other thirty years before were meeting on the corner now in this small town. They had to learn how to get on together, because we were living in this small town. They would give a nod of recognition, though they still wouldn’t speak. It was too painful and too hard to keep up hatred for that long. So they would give a begrudging nod and grumble a “How ya doing.” And this town is so small that these people would see each other often.

One of the things I always thought, no matter how ideologically apart from people you are, you should be civil to them because we’re all human.

You write about it in “Green Suede Shoes,” and I have seen this in my own life as well, about the power of one’s cultural language and the affect of not having words to express certain feelings can lead to a strange imbalance, so to speak. So by getting back in touch with the language, in this case Gaelic, you can regain some power that has been previously lost. I am curious about how you started using Gaelic in your music, and I wonder if it has satisfied something in your spirit by doing so.

I first started using Gaelic when I was taking time off from music after the Major Thinkers, an earlier band I was in, broke up and I was writing music for the theater. The reason I did that was because the dancers I was working with in the theater didn’t want to dance to English words. And yet, I wasn’t this great instrumentalist. I was able to play piano and keyboards and stuff like that but I was no wizard at it. So I found it easier to sing melodies, but I couldn’t sing in english.

So I put myself in sort of a trance, and I would sing words that would come to mind. And I found that I was coming up with these little statements, though my Gaelic had gotten pretty bad up to that time. So these statements were coming from my subconscious without me even knowing it. Just lately, in the last three or four months, I’ve been into re-learning Gaelic. I’ve been taking classes.

Why I went back to do do it was because I realized that when I used to listen to people speak Gaelic, and when I spoke it myself, there was a way of expressing that came deeper than English. And I’m a different person when I’m speaking it, a nicer person maybe even. It’s a gentler language. I mean it can be very earthy too, but there’s a civility to it. And I relate to people in a different way through it, and I was interested to re-explore that again, because it’s a way to find out certain things about yourself. It’s also a great language to write music to. It’s very earthy, very lusty.

The Irish character that we see as Irish-Americans, as being Irish, was formed more in the last 150 years by religion. Not just the Catholic religion, but a form of Catholicism called Jansensim, which came from the continent, it came from Europe. And it supplanted the Irish church and made people much more conservative. The Irish people were very bawdy and rowdy, very Elizabethian like, the laguage is very earthy, these were people from the land. People from the land are used to sex in a certain way, and could talk about it.

So I was interested in getting back to that, and sweeping away this foreignness that we take to be Irish, but it’s not really. It’s a new coating or lacquer that is put on us since the Famine, in 1847. So basically 160 years. The people before the Famine were different.

After the Famine the priests had to go to Europe and they were going to certain ports close to Ireland. The seminaries they went to tended to be run by followers of Bishop Jansen.

And they tended to bring back that form of conservative theology with them.

And Protestantism?

I think I wrote about this in either “Green Suede Shoes,” or in an article for the Irish Echo, I write a column every week for that paper. Anyway, I always thought that the Irish were afflicted with the two worst types of Christianity. There was Jansenism, Catholicism, and Calvinist Presbyterianism in the North. And the two of them are like rocks against each other, and that’s part of the problem. Whereas the people who are more in the center, the British type of Episcopalian and the Church of England types weren’t as bad as this aspect of Presbyterianism. This totally god-fearing and narrow form of Christianity that hasn’t worked for the people.

We have this Jansenist form in the US because of Irish Catholicism. You get different forms of it here. There is a lot of feminists in the Church. But there is this authoritarianism that comes down from the Pope that is not good for Catholicism. And it perverts the openness of Catholicism that you’d find sometimes in Spain or Italy, where it’s sunnier and the belief of whatever will be will be. Where we are not going to go out and kill anyone, but maybe will love them to death.

So you’d have to rebel against it like I did, and then you lose it. Now I’m only getting back and retained some of the Catholic values and mixed them in with other types of religion in my personal life. Lots of times, though, people have to rebel against it so hard that they lose them all. Whereas there is a lot of great stuff in Catholicism, and there are a lot of great people out there practicing, especially priests and brothers and laypeople.

But what I didn’t admire and fought against as a youth was the whole bishop thing. That was a reason why there was all these problems in Ireland with child abuse becuase nobody was speaking up. We were told to keep it down. I was around it. I didn’t see it that much, but it was there. You could feel it like a disease, and we weren’t speaking up against it, because you didn’t look for it and you wanted to keep away from it.

I just watched this documentary called Deliver Us From Evil. It focuses on child abuse within the Catholic Church – of the sexual nature, molestation and rape. And it starts out on one priest, this guy Father O’Grady. He’s from Ireland, but he was stationed out in California. He is a pedophile and the movie then runs through some of the people’s lives that he affected and messed with.

The film then opens up to give an explanation as to why some clergy commit sexual abuses, and then it goes even further and runs through the history of how long this stuff as been going on for, and its centuries. Then a connection is drawn, and this is not conspiracy, this is legal provable stuff of how the present Pope, Benedict, has had knowledge of some of the stuff going on. So this is some deep disturbing stuff.

This brings me to my question. Sinead O’Connor – in the 90’s she was on top of the world, then she went on to Saturday Night Live and sang the Bob Marley song “War.” At the end of the song she said “Fight the real enemy,” and tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II. For this she was lambasted, blacklisted, and her career took a major hit. I watched an interview of her explaining why she did that, and she said she did that because she was one of the first people to feel really moved to say something about all the child abuse going on in the church, and that SNL stuff was her demonstration.

Well let me first talk about the Church stuff. One of the awful things about the child abuse is that so many priests have been tarred with that, and it’s only a small percentage who have commited these acts. There are all these other guys and nuns and lay people doing all this good work, but they are scared now.

I have a friend who is a priest and was a head master in a prominant school. And he told me at the time that he had to stop doing what he used to do, which was being supportive of the boys. And he would not be alone with a boy anymore. The door used to be always wide open, but becuase of the scandal boys couldn’t come to him with their problems, because they would think someone is out in the corridor. But he had to do that, he couldn’t take the chance of some boy saying that he did something to him. It has really hurt a lot of people, apart from the people who were abused.

With Sinead, her problem was that she didn’t set it up by maybe first saying, “This is what I’m protesting against.” And people saw it as a direct attack on the Pope. And that’s Sinead’s way. I interviewed her on Sirius about a year ago, and she doesn’t suffer fools. You can say that. She is there with a point of view. She can be articulate, but she can also miss what she is setting up to say. And that was her big problem with that night. It did wreck her career, and I was surprised that it did.

I was at the show in Madison Square Garden where she walked off, and she shouldn’t have. There was around 18,000 people in the Garden, and maybe 200 booing. I thought it was a cop-out to walk off. Neil Young said it at the time. He said, “When I was doing the Trans album, I got booed every night. But it wasn’t just 200 people it was the whole place that was booing me.” She shouldn’t have walked off that night, I thought. Or else she should have played some Black 47 shows in the Bronx just to toughen her up.

She just didn’t set things up right, and she was probably under a lot of pressure. There was also the feeling among a lot of people that she was doing it for publicity. Again that’s the thing, if she had said before the show, “I’d like to make a statement.” And then she could have still ripped the picture up.

To backtrack a bit – you are saying that within the church there are the good people and there are predators. This reflects in the film, they show this man Father Tom Canon, who is an activist and an organizer, and he was part of the case against the sexual predators. He is also a Catholic.

Where he draws a real interesting point is by saying that there was a time around 1,500 years ago when priests and popes were allowed to marry. And see, the money that they had within their own families could then be passed down when they died. But then this thing happened where the vow of celibacy became doctrine, and that money that would have been passed down then went to the church and the Vatican became a very political structure.

Well, the problem with the church was that it became a corporation. This is what I used to fight against back in Wexford, and Wexford was run by the chiurch. And it was whatever is right for the corporation is right for the people in it. And that was one of the strengths of the church, and why it’s lasted so long. And that’s also been its greatest weakness. In that, it’s not of the people. there was this command structure. Pope, Cardinals, Bishops, Priests, Curad, Peon, and Women. Women had no part of it but to be servants and teachers. And women should be running the church, just like they run the house. The church will run better.

So going back to Sinead O’Connor and where I notice where she has gone in her career. First, she was singing the Bob Marley song “War” on Saturday Night Live. She also had the Rastafarian colors in the picture frame when singing. Also, from my understanding, a large portion of Rastafarianism is very opposed to the Vatican and the Pope, so in one degree that fit in with what she was doing that night. I think she is a Rastafarian now, and she released not too long ago an album of Rasta songs, and she calls them Rasta and not Reggae.

She is an amazing person. I give her respect. She is an amazing singer. She sang three or four for me in the studio, when I interviewed her. I was like, “I can’t believe this. She’s singing right to me.” I was almost embarassed. It was just such a feast, and she was so in tune. So dramatic, and yet so self-effacing. She is a complicated person. A good person.

She also made a Gaelic-langauge album, Sean-Nos Nua. I saw a comment on YouTube, when I was watching one of the videos, this person made the correlation about similarity between the tradtional Gaelic song structure and Reggae rhythms.

Well Black 47 were the ones that started that song in that rhythm. It was on the song “Fire of Freedom” on the album of the same name. She uses the same melody with the same Reggae rhyhtms. I’m not saying that she copied it from us. It definitely was an obvious way to go with it.

Why do you think so?

There is a deeper thing, and it may come from this. In 1649, when Cromwell defeated the Irish. The sugar plantations had just started in the West Indies, in Jamaica and some of the various islands. Cromwell had all these young Irish people which he had captured, and he felt that he had to get rid of all these people, so he sent them out to the West Indies to be slaves. So the Irish were the first slaves out there. A generation later the African slaves were sent there, and so they intermarried and that’s where Reggae came from.

If you liseten to the beginning of “Redemption Song” by Bob Marley, that’s an old Gaelic melody that he must have heard.

Do you know what the name of that melody is?

No, it’s Marley’s take on what the Gaelic melody was. Check it out.

Sure will. I’d like to ask you about Lester Bangs.

Sure. Lester was a great guy. He’s not as he was portrayed because he had a public persona and a private one. And it took awhile to peel back the public one, because he cultivated it over the years. His public one was, “I’m totally into garage rock, that’s all I live for.” His private one was that he knew a huge amount of all types of music. He was really into, for instance, Bob Seger. He just loved music.

Lester’s big problem was that he wanted to be an artist, and not someone writing about them. Even though he was the best ever at that. He didn’t see that as anything great. That was his demon, I would say. He was very generous in ways. He could be really belligerent when he was drinking or doing pills, but he was mostly a big shaggy dog of a guy. Once you put away all the stuff, you could sit and talk to him for hours, he was a total music fan, and not just the music he said he was into.

He was a good guy. I miss him. I often wonder what he would have been doing all those years. What he would think of all the different music. I don’t think he would be happy now, that’s the thing. He believed totally in the dream of rock ‘n’ roll as being something that was transcendent. That doesn’t mean he couldn’t go out and write a book for money or something. He knew how to stay alive, but that was his basic reason for being. Music transcended everything, that was the best thing.

Yeah, I’ve read his articles about the Clash and whatnot. That whole point you mention about the dream of music, I grew up in a more corporatized musical environment. And I saw a banner of the Clash on the way over here being used on the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame outlet store, which is sponsored by some bank. It’s funny how it is today, it’s just very different.

It is different. The ’60s lasted until ’83. The ’70s always gets run down as a bad period for music, because of disco. But the ’70s had Punk and it had Reggae, it was an inspired time. Lester was there but he could see the end coming, and he got depressed over it. He could see how MTV and things like that were destroying it. And how the corporate world would eventually destroy it. And that depressed him a lot. Probably because he was thinking, “Where do I fit in?”

Yeah, like where does the soul fit into this debacle?

Yeah, him thinking, “Am I going to have to go out and write bullshit?”

Right on. So I’d like to ask you about where you think the current state of Northern Ireland, and the rest of Ireland, is at?

Black 47 were in Northern Ireland last November (’08?) and I was stunned in Belfast, because some of the areas I was going into in, I didn’t recognize them. There is still the hatred there, it didn’t really go away. The Catholic Jansenism and the Presbyterian Calvinists, they’re there but it’s now kind of under the surface. Because it’s not as cool anymore to be that way. The young had basically gotten money for the first time.

I was there, and had gotten an award from Joe Doherty. He gave me that from the prisoners for different works that the band had done. He came up to Dublin to give me that, and we were sitting in a hotel, the Burlington with its huge lobby, probably three times the size of this apartment. And we were sitting there and he looked at me and said, “What do you see?” Was this some sort of Existential question?

I said, “I see a lot of people on cells phones and texting.”

Then he said, “What does that mean?”

I said, “I don’t know.” He was urging my thought somewhere, but I didn’t quite see what he was getting at.

Then he said, “Now think of my generation. We had nothing. We didn’t have toilets in the house, they were in a shed down in the back of our yard. We had nothing. So for us to blow up the place, or to protest – we didn’t care if we went to jail. Not a big deal, beacause everyone you knew, or a lot of people you knew, were probably there. But these young people, to their credit, they have something. You can’t ask them to do what we did. The world we knew is over. Everything will be political from this point on, if you can get them to get involved with politics, but there is going to be no more shooting or anything.”

I thought that was very on point. Because once money comes into it, and people have a stake in the society, they don’t want to blow it up anymore. And that’s the big difference in the North the way it is now, and the way I remembered it.

Now everything has changed in the last six months in the North and the South because the whole bottom has fallen out from both economies. Now I don’t know what is going to happen with that beacuse it happened so suddenly over there. There was a point where it was even hard to relate to young Irish people, because there was so much money compared to what the rest of us came from.

When I came up, there weren’t these huge gaps in income, you might have had a little more or a little less than those around you. But now that gap has contracted, and I don’t know what that’s going to mean for the country. It will probably be better for the soul of the country, but I don’t know about those other parts.

Well speaking about the “soul” part of the country. It’s strange, I know that in the late ’90s and early 2000s there was an epidemic of suicides among young people in rural areas. I had three friends who all killed themselves in like a year’s time. This was a tiny village where this happened. I have heard from a lot of people out there that this was also happening in many towns all over the country. I have my own ideas as to way this is. In times of mass transtion something like this takes place.

Yeah, and this has continued. Where I’m from in Wexford, there’s a huge epidemic of it. There is a town in Wexford where there a low bridge, and they had to put a guard on it because so many people were jumping from it. I couldn’t get over the amount of suicides over there. Part of it, I think, is now not having the Church. The Church was always that bond that kept people together. So when the Church went out with the accusations of the sexual molestations, when that was destroyed, there was a certain social bond that was destroyed too as well. So for the young people coming up now, they don’t have the church to fight against or to gain solace within it.

Let’s talk about Black 47’s newest relase, the Iraq album. How was it received. You mentioned earlier it was a little contentious.

It was much more than that. By the time the album came out last March, most of the anger against the war had dissapated a good bit. We were against the war the night it was declared. We played a show at the Knitting Factory that night, and there were scuffles in the audience. People were outraged. I started writing songs pretty instantly about it.

Everywhere we played for three years was a nightmare, because someone was going to get up and walk out and get in your face as they left, and the other people who were against the war didn’t stick up for us either. That was one thing that struck me too. It wasn’t that there would be more people there against the war, but nobody wanted to take a stand on it. It was really just a bad time in American life.

And it’s a bad time now because the war is just being pushed under the rug. These kids are going to get back from Iraq, and it’s going to be huge problems. because now with the economic downturns, it’s going to be “get in line.” You are not going to get up to the front to get a job. And some of the kids who I have met that have been over there are damaged. Take a kid, he’s 18 or 19, all he knows about life are video games, he’s over in Iraq, everyone hates him, they are shooting at him. He’s living in over 100 degree temperatures. Once he is back, he can’t really talk about it, because now no one here gives a goddamn.

I saw it happen with the Vietnam vets. People wouldn’t go near them becuase we all thought they were crazy. That’s going to be happening a lot with this war. The US and all of us, because even if we protested we didn’t protest enough, because that was a war that shouldn’t have happened and now the chickens are coming home to roost.

What do you think about Obama, with his first day in office closes Guatanamo Bay, etc. Are you optimistic or hopeful about the Obama presidency?

Yeah, I’m optimistic. Basically, what it is is America regaining its equilibrium. Showing that America doesn’t like torture. Americans are the good guys, and it should be seen that way. When we were growing up, Americans were always the good guys. Now that’s not what young people see from around the world. So Obama has to redress that. It will happen.

The great thing about the world is how it’s going so much faster than it was. So in the past when damage was done, it would take generations to get fixed. Now for whatever reason everything is just going so fast.