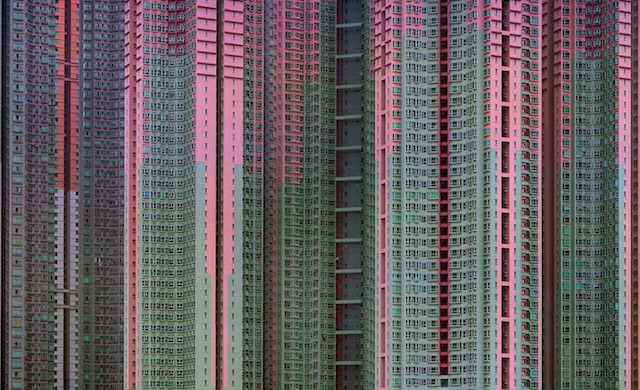

This blog’s dazzling featured image is by Michael Wolf, a 60 year old German photographer who moved to Hong Kong in 1994 [1]. He’s worked for Stern magazine before setting his sights on the world’s “megacities,” which are like cities but much, much bigger. Many of these images defy our sense of reality: they must be out of a cyberpunk dystopia, and yet, here they are, towering over landscapes predominantly in Asia.

According to Wolf, while cities have a population of 5 million or so, a megacity can reach up to 25 million people. How do that many people fit into a cramped space? Through massive architectural design. Efficiency. Industry. Compactness. Towering arrangements of steel and concrete house hundreds of thousands of people in tight, glittering cyberpunk slabs. The sheer size of these buildings creates what Wolf calls “The Architecture of Density,” often resembling a kind of vast tapestry.

How do the denizens of these futurescapes feel about living there? “They always say their apartment complexes are so convenient,” Wolf tells VICE, “You take the elevator and you have a shopping mall, a subway station and a school. But… every single person would like to live on a smaller scale.”

Wolf is interested in the kind of “creativity” and “resourcefulness” that human beings respond with in these megalithic environments. I’m not sure sure I like that civilization’s most recent cityscapes are headed in this direction. Perhaps, with peak oil, climate change, and systemic environmental reform, we won’t have to keep trudging along in the direction of mountainous human insect hives (how many of us would really want that?).

Frank Lloyd Wright once commented that “to look at the plan of a great City is to look at something like the cross-section of a fibrous tumor.” One wonders how Wright might gasp at a city like Hong Kong. Wright, of course, had his own visions of the future: Zen-influenced aesthetics and eco-friendly utopian designs like “Broadacre,” the suburb-as-city imagineered straight out of a Star Trek The Next Generation episode [2], or “Usonia” homes, which were “green before it had a name.” [3]

Wright, in direct contrast to these megacities, wanted everything to get back to nature and forego the modern industrial city entirely. He was, in other words, a utopian, desiring to start from scratch. Today our problems are exceedingly more complex, and the kind of architectural vision needed to make places like Hong Kong or N.Y.C. less like industrial monsters and more human is a task of equal imagination to the Blade Runner cityscape. While he was surely a tad arrogant, Wright spoke an inkling of truth when he wrote that the architects were “essential interpreters of America’s humanity.” Perhaps we can scale that up to the planetary level, as Buckminster Fuller does with his “design revolution” or Paolo Soleri’s “arcology.” [4]

Others might meditate upon Hong Kong as mega-city with more optimism. Teilhard de Chardin, a Jesuit theologian who popularized the concept of the “noosphere” in The Phenomenon of Man, believed the modern city and its industrialized polity an early harbinger of the planetization of the human species. A kind of psychic-pressure, constructed out of the sum-total of human entanglement with both each other and the rest of the biosphere [5]. Teilhard’s incipient recognition of interdependence has since gone on to influence ecological-minded theologies, like Thomas Berry and, most recently, Sister Elizabeth Johnson in her new book: Ask The Beasts: Darwin and the God of Love.

In Passages About Earth, historian William Irwin Thompson comments on Soleri’s “arcology,” a planetary-minded design for future cities that should implode rather than explode, as megacities seem to be doing: “it should imitate evolution and complexity itself through intense miniaturization… The city must contract, intensify, and miniaturize civilization.” [6]

“The opposite of the miniaturization of technology is the exponential growth of giantism, bureaucracy, and the technologizing of human beings in a totally mechanized culture,” [7] writes Thompson in Darkness and Scattered Light. Beautifully captured in Wolf’s photography is a triumph of massive engineering, utilitarian thought structures made manifest as industrial dystopia. Opposite indeed. As a psycho-technic artifact, what can the megacity tell us about the current state of the noosphere, if anything?

It could be that megacities aren’t a vision of cyberpunk futures as much as they are an evolutionary cul-de-sac; like the gigantic bones of Godzilla-sized dinosaurs, the mega-cities of today are the equivalent of the Greek’s mythic Titans and elementals. Towering over the world — if only for a brief while — they exist as apparitions of the future through the eyes of an industrialized past.

The megacity is the final huzzah of what cultural philosopher Jean Gebser called “ratio” mind — a structure of human consciousness oriented toward quantifying space and discursive, mechanical reasoning — racing to a finish line which is, in actuality, an event horizon; a singularity from which it will never recover [8].

While I certainly get my kicks from contemplating cyberpunk cities, I’d like to end with a brief imaginative hypothesis — off cyberpunk and into slipstream, so to speak. What might a city look like in a post-industrial future?

In my mind, anyway, the true scifi future of the city lies in its ability to etherealize. You take your city with you. Cities of the future are holographic. They might fit in your pocket, or better yet, are hidden between the dimensional cracks of natural landscapes — like the mythical realm of the Faerie or gnome. Future cities are nomadological, in that they can be brought with us as we follow the line-of-flight from the mechano-industrial tomb of civilization. [9] Cultural evolution swallows up civilization as a brief interlude in an otherwise larger, and longer nomadic history.

To draw this riff on the city to a close, here is William Irwin Thompson on his idea of the city-as-concert, oddly reminiscent of today’s experimental festival culture and temporary communities like Burning Man [10]:

“I imagine a future architecture in which you turn on a building the way we now turn on lights. These buildings will be temporary like concerts, and not enduring like the pyramids; and so when the use of the building is finished, the people can move on… The culture will be similar to the nomadic way of life of the old paleolithic hunters and gatherers; the people will carry their cultures in their souls.” [11]

[1] Initial inspiration for this writing project came from VICE’s “Photographing the Beauty and Inhumanity of Asia’s Cramped Megacities.”

[2] See Paleofuture’s “Broadacre City: Frank Loyd Wright’s Unbuilt Suburban Utopia“

[3] “Green Before It Had a Name” via The New York Times

[4] See Arcosanti.org.

[5] See Thomas Berry’s “Teilhard de Chardin in the Age of Ecology.” An excellent, hour long film.

[6] Passages About Earth, pg. 38

[7] Darkness and Scattered Light, pg. 72

[8] See Jean Gebser’s Ever-Present Origin, 1949.

[9] Deleuzian term I’ve picked up from cultural critic, John David Ebert, to describe digital culture. See The New Media Invasion: Digital Technologies and the World They Unmake.

[10] See Talat Philip’s “The First Extra-Terrestrial City on Earth.” A lot more can be said about this idea, but perhaps it’s more appropriate to consider transient cities like Burning Man/Black Rock City to be early forerunners of tomorrow’s techno-nomadism, an alternative envisioning of the cyberpunk city for the “integral city,” to borrow Jean Gebser’s terminology; a city that’s been miniaturized within a larger, digital-imaginal space.

[11] Darkness and Scattered Light, pg 176.