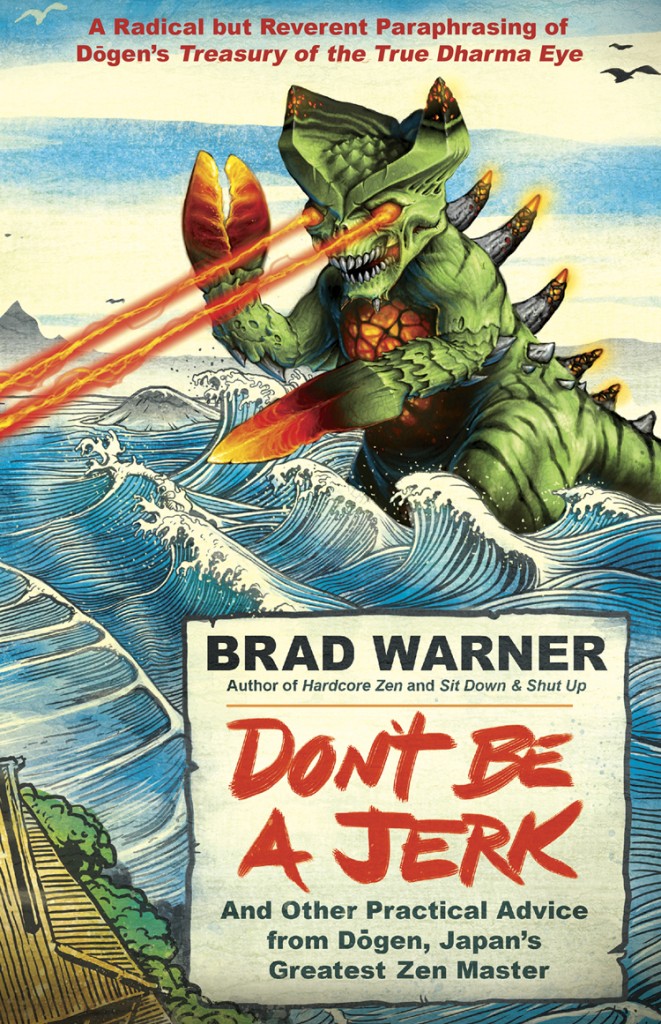

The following is excerpted from Don’t Be a Jerk by Brad Warner, published by New World Library.

There probably is not one teaching in the entire Buddhist canon that causes more confusion than the teaching of no-self. The existence of a self is taken as a given by pretty much every religion and philosophy, apart from Buddhism. In fact, the idea of no-self is so difficult that there are even sects of Buddhism that find workarounds to redefine self and try to sneak it in through the back door somehow.

When I first encountered this idea of no-self, I conceived of it the way most people do when they first come across it. First off, it seemed completely absurd. It was the denial of something that I could clearly see for myself was true.

You can deny the existence of the Loch Ness Monster or Bigfoot. You can tell me there’s no Santa Claus or Easter Bunny. But the existence of self? Come on! That’s obvious. René Descartes proved the existence of self with a simple five-word formula: “I think, therefore I am.” End of argument. Self must exist because here I myself am, thinking of things and writing them down, and here you yourself are reading them. Who else could be doing these things if it wasn’t my self and your self? How could anyone with any common sense at all deny that?

But okay. I was game to try. I respected my first Zen teacher, and I didn’t think he would tell me lies. He believed there was no self, and it seemed like this belief made his life better. My life was not going that great and I wanted some of whatever it was that seemed to make his work. Besides that, the rest of what he said about Buddhist philosophy and practice made sense. Or, when it didn’t make sense, at least it usually didn’t feel like it was denying something I could clearly see was true. So I started working with the idea of no-self.

My initial forays went something like this. I figured I had a self but that it was my job to eradicate it in order to feel happier and more peaceful. My understanding of self was that it included my personal jumble of likes and dislikes, attitudes, ideals, personal history, beliefs, habits, hobbies, and so on. I figured I had to somehow get rid of all that and become a clean, blank slate. If I could whitewash everything I considered to be “me,” I would be rid of self and then maybe I’d stop being such a wreck all the time. So I went about trying to do that.

But as I was doing that, I started to realize that my first teacher, Tim, didn’t appear to have erased his personality. He liked certain things and disliked others. Just like me, he adored Star Trek but thought Lost in Space was pretty dull. He had very specific opinions on politics. He had some rather peculiar habits that he didn’t seem keen to eradicate. He was, in fact, a very strong personality, a very strong self, if that’s how self was defined. This was one of the things I liked about him. So what was I doing trying to erase my personality?

Tim really liked a book called Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki, which I’ve already mentioned, so I read that through a few times. In the chapter titled “Emptiness” Suzuki says, “When you study Buddhism, you should have a general house cleaning of your mind. You must take everything out of your room and clean it thoroughly. If it is necessary, you may bring everything back in again. You may want many things, so one by one you can bring them back. But if they are not necessary, there is no need to keep them.”

That actually kind of scared me. For one thing, I’m a fairly messy person. I didn’t like cleaning my room at all in those days. There are a few photos of rooms I lived in when I was younger that make me cringe when I see them now. And even today I’m probably not most people’s image of the ideal housekeeper. But that isn’t what really put me off. What made me truly scared was the idea that I’d have to do a house cleaning of my mind.

Nowadays, having lived in Japan for eleven years, I know precisely the type of house cleaning Suzuki was thinking of when he said this. In Japan there’s a tradition of doing something called osoji at least once a year. Osoji literally translates as something like “big cleaning.” It’s like what we call spring cleaning, but more extensive than what most Americans do when they spring clean. In Japan, during osoji time, you take everything out of the house. And I do mean everything! The books, the knickknacks, the dishes, the bookshelves, the furniture — everything that’s not nailed down gets taken outside. Sometimes even the stuff that is nailed down gets taken apart and moved outside. Then you clean up the house thoroughly, after which you clean up all the stuff you took out, and then you start putting it back inside. It’s a pretty massive task. When you’re putting stuff back in, you get to see how much useless junk you’ve accumulated since the last osoji and you always end up throwing a lot of it away.

Osoji usually takes place around New Year’s Day, a time during which most businesses are closed for five days, although the tradition of remaining closed for five days is slowly starting to erode. So not only is this tough work, but it’s usually cold as hell outside when you’re doing all that scrubbing. When I first encountered this tradition it seemed like madness. But once you’re done, your house feels great!

I didn’t know anything about osoji when I first read Suzuki’s book, but now that I do I get an even clearer picture of what he was saying. If I’d known then what I know now, I’m sure I would have found the prospect even scarier.

What he’s talking about is metaphorically taking everything that you think of as your self out of your head and looking at it carefully and critically to see if it’s really necessary. He does say you can bring some of it back inside. But read between the lines, and you can see that he’s implying that there’s a lot of stuff in there you won’t want to bring back.

This idea scared me because it wasn’t just paperback novels I’d finished reading or broken guitar effects boxes I finally had to admit I’d never get around to fixing that he was telling me to throw away. He was telling me to throw away pieces of me! That is a much scarier prospect. It wasn’t just scary. It sounded utterly impossible.

For me this was especially tough because I prided myself on being a true individualist. I got through high school knowing that even if I was just a nerd boy that the pretty girls ignored, at least I was truer to myself than the jocks and preppies who liked what everybody else liked and dressed the way everybody else dressed. I dared to be different and I was, I thought, justifiably conceited about it! I had to be! It was all I had going for me!

Now here I was just a couple years out of that mess, being told to clear all that stuff out. What would I have left if I did? Would I become a mindless vegetable? Would I turn into one of those culties who just stares blankly off into space all the time? Or worse, would I become just like the jocks and preppies I hated, accepting everything the mainstream media told me because I had no self and therefore no opinions of my own? Or would I be opening myself up to being brainwashed by my teachers? Would I be just like the pod people from Invasion of the Body Snatchers? The prospects were not attractive!

But the idea of no-self isn’t like that at all. It’s not that we have a self and we are being asked to get rid of it. There is something real that we call “self” and that we ascribe certain characteristics to. It’s just that once we call that thing “self” we are already on the wrong track, and anything else we say about it will be mistaken.

It would be ridiculous to insist that the aspects of our experience indicating that we are autonomous individuals with our unique history, personality, and point of view simply do not exist. I have my own credit cards and driver’s license, which you cannot use. I know the password to my Wi-Fi at home, and you do not. I remember things that happened in my life that I could not possibly convey to you, even if I tried my hardest. I have opinions that you do not and probably a few you couldn’t even comprehend, the same way I cannot fathom why some people hold the opinions they hold. All this and more applies to you as well and to every human being or animal who has ever lived.

When Buddhists talk about no-self they are not saying all the foregoing is false, nor are they saying it’s all true but that we have to utterly destroy these aspects of who we are. Rather, they are saying that applying the idea of self to this real stuff is a mistake.

The word used in early Buddhist writings for the concept of self is atman. Atman was an idea propagated by many Indian philosophers and is similar to the Christian idea of the soul. It starts from the sense of “I am” that all of us experience. This “I am” feeling is taken as evidence that there is a permanent abiding something in us that remains stable and constant throughout the changes we experience. Thus the soul you had as a four-year-old child is the same soul you have today. This soul is different from the body because even though the body clearly changes, the soul does not. Many philosophers further extrapolate that the soul survives the death of the body. This makes sense if we accept the basic idea of the soul. If you believe that the soul remains unchanged while the body ages, it follows that the soul is not the body and it therefore follows that the soul could go on even after the body decays and dies.

The Buddha completely rejected this idea. First of all, he noticed that what we refer to as the soul or the atman does change. Our personalities do not remain static throughout our lives. We mature internally as well as externally. The Buddha did not accept the idea that body and mind were two different kinds of substance.

Yet something experiences the world uniquely in the case of each one of us. You are reading this book. Somehow my thoughts about self are being conveyed to you across time and space. My thoughts are not exactly the same as yours, or you wouldn’t have bought this book. You are not me, and I am not you. What are we to do with that except say that you have a self, and so do I? Even if we don’t accept the idea of the immortality of the soul or the idea that mind is made of some kind of ethereal substance that is different from matter, we have to accept that your mind and my mind are not the same mind. Otherwise we wouldn’t need to have conversations or read books or watch movies or listen to music in order to access each other’s thoughts and feelings.

Most of us only ever experience that way of looking at things. No, that’s not exactly right. Most of us are taught that looking at things this way is the only correct way of understanding the world. I think everyone experiences the other side of the equation at some point in their lives. As children, our sense of self is much more fluid than it becomes later. We also have moments of transcendence when the barriers between ourselves and others fade away. Sometimes this happens during sex. Sometimes it happens in large public gatherings like concerts or sporting events. Sometimes it happens in religious services and ceremonies. We all know about this other side of human experience, but we are conditioned to disregard it. Or we imagine that it only happens at rare, special times and places. We miss the fact that this transcendence is actually continuously happening throughout every moment of every day.

Meditation practice helps make this clearer. Moments of transcendence and oneness no longer seem like anomalies. You start to notice that your individual identity and the identity of the universe itself are not two separate things.

Certain Indian philosophers who meditated took this as evidence that the individual atman was part of a supreme atman that was basically the soul of the entire universe. They called this super-atman “Brahman.” And just to confuse those of us outside India, they also called certain people who preached this idea Brahmin and named their chief god Brahma. Be that as it may, this Brahman is said to be sat-chit-ananda, or “being, consciousness, and bliss.”

Yet, like the atman, Brahman is supposed to be something apart from the material universe. The Buddha could see no reason to believe in the existence of something beyond the material universe. It’s not that he thought matter was the only thing there was. Rather, he saw that matter and the immaterial were different aspects of the same unified reality. Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.

The idea of no-self means that we do not interrupt this oneness with our individuality. In the January/February 1985 issue of Matter magazine, my all-time favorite singer-songwriter, Robyn Hitchcock, told an interviewer, “Inasmuch as a mind can discuss itself — it’s a bit like a mirror looking at itself, only I don’t know how much truth there is in that. You put two mirrors up against each other, and there’s infinity, but you can never see it, ’cause your head blocks it off.” This is a remarkably astute metaphor for the problems inherent in looking at the true nature of what we call self.

We are both individuals and expressions of the universe. These are not mutually exclusive. Do–gen talks about this a lot throughout Shøbøgenzø because it was as difficult an idea for him and his students as it is for us. The next chapter contains some of his best lines on the subject of no-self. Let’s take a look!

***