This article originally appeared on Techgnosis.

The spiritual superhero of the baby boomers was the guru. But where the guru once hovered with his beatific smile, the shaman now shakes his stuff: an earthier, more pragmatic icon of mystical powers more suited to our era’s green anxieties. Now a significant figure for scholarly discourses as well as popular ones, the shaman, and especially the ayahuasca-swilling Amazonian variety, has not only stepped forward as a vehicle of archaic spirituality but has become — as the gazillions of bedazzled Avatar initiates can attest — a seductive site of fantasy and projection. For many of the aya tourists now hustling down to Peru in droves, or the untold thousands dropping 300 bucks or so to drink in their own Euro-American backyard, the man with the rattle (and his less common female compatriots) has become a visionary Rorschach blot: a New Age therapist, an avatar of environmentalism, a psychedelic captain fantastic.

This is why we need Stephan Beyer’s new book, the magisterial Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon. In this tome, Beyer has found the sweet spot between scholarly and popular writing, the otherworldly and the disenchanted, participation and observation; the result is the best or at least most comprehensive book I have seen on ayahuasca.

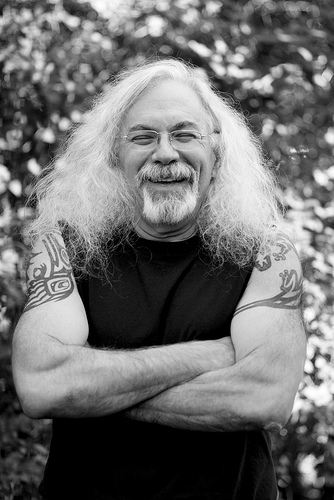

In addition to a law degree, Beyer hold doctorates in psychology and religious studies, but his discovery of ayahuasca was more than intellectual. Arriving in the Amazon to practice wilderness survival, he soon realized that learning about the jungle meant learning about the spirit of its plants. So he apprenticed himself to two mestizo teachers named Don Roberto and Dona Maria. He studied ceremony, healing plants and the inevitable sorcery tactics with them and others for many years.

While Beyer’s personal tale enlivens Singing to the Plants, he resisted the temptation to write a memoir. Instead, he allowed his experiences to round out, deepen, and authenticate what is a manifestly solid work of scholarship designed, happily, for the rest of us. Beyer’s book offers broad discussions more than new data or highly focused arguments; despite some arcane and fascinating discussions of magic stones and sex with plant spirits, I suspect that ethnobotanists and anthropologists familiar with the Amazon will find relatively few surprises. But the ant hills of detail are not the point. Singing to the Plants is designed to inform a wider audience — and gently bust some myths — by presenting this almost literally kaleidoscopic phenomenon through a number of distinct lenses: anthropology, ethnobotany, pharmacology, psychology, international law, cultural politics, and magic both crafty and occult.

I knew I was gonna love this book when, after presenting illuminating and occasionally disturbing tales about his own teachers, Beyer frames the shaman’s work through an understanding of performance. Like stage magicians (or western doctors), shamans are, on one level, performers with an audience, and aspects of their performance are deeply linked with everything from the sleight of hand of conjurers to costume. Beyer’s breakdown of shamanic performance is thorough and fascinating, with chapters on “Phlegm and Darts,” “Sucking and Blowing,” and “Harm.” I was particularly wowed with his discussion of shamanic sounds and songs, and especially the haunting, nasal whine of icaros. In addition to presenting research on how these sacred songs are passed on and improvised, he emphasizes the abstract effects produced when lyrics break down into alien tongues or pure sounds like whistles, hacks, and hums, whose “correct resonance and vibration [are] more important” than meaning.

Beyer roots shamanic performance and the ayahuasca ceremony in the body. As initiates know, the aya ritual can be an intensely physical experience — a woozy, vibrating, literally gut-wrenching dance of coughing, spitting, burping, and, of course, puking. (Beyer spends a lot of time with phlegm, for example, an aspect of shamanic performance that is not always emphasized north of the border.) This carnal and even carnivalesque dimension reminds us that ayahuasca is not a mystic or transcendentalist affair, and resists the highly internalized or even disembodied approaches that many American seekers bring to it, with their background in meditation or other more internalized psychedelics. Along these lines, Beyer makes the provocative argument — which is growing on me the more I think about it — that DMT (the most active ingredient in ayahausca) deserves to be classed as a “hallucinogen” distinct from “entheogens” like LSD and mescaline, which peel away the layers of the self to reveal the god within (the literal meaning of entheogen). In contrast, according to Beyer, DMT unveils a visionary world out there, one that is not only believable but seemingly inhabited.

While Beyer uses plenty of concepts and lingo drawn from anthropology and psychology, he does not offer these views in a spirit of reductionism. After all, Beyer has been learning the ropes for years, and has spent far too much time wrestling with wizardry to try to dissipate its dialectic of healing and harming with the word-spells of academe. Beyer’s critical discussions only help illuminate the central mystery with greater intensity. So while he offers up useful maps of the phenomenology of visionary states, when it comes to talking about the spirits themselves, Beyer just calls ‘em as he sees ‘em. Spirits — or “doctores” — are simply part of the picture; there is no need to reduce them to projections or myths — they harm and they heal, converse and confuse. As long as we remain aware of the various contexts which structure our encounters, we have every reason to acknowledge and engage the spirits as part of our world — an aspect of nature and consciousness, but also — and this is crucial — an aspect of modernity itself.

In contrast to many Euro-American aya fans, who fetishize the otherness of the Amazonian shaman, Beyer does not characterize the Amazon’s techniques of religious ecstasy as archaic residues free from any contamination from today’s globalized world. The culture of ayahuasca is both stronger and weaker than that, more expansively eclectic and also more ordinary. Beyer notes that Dona Maria’s spirit doctors regularly spoke in “computer language,” just as an earlier generation of shamans used metaphors of electro-magnetism and radio to characterize the spirit world. The UFOs found scattered through Pablo Amaringo’s paintings are icons of this visionary futurism. But they are equally signs of the syncretic, mix-and-match, opportunistic, and almost willfully contaminated aspects of mestizo culture — which must make itself up as it slips along between jungle and city, modernity and the indigenous forest. That said, Beyer is all too aware of the political, economic, and spiritual costs of the Amazon’s deepening imbrication with global flows of capital and culture-an encounter that is increasingly taking place through the medium of ayahuasca tourism, which receives a sharp if too short treatment here.

If shamans are not frozen under glass, they are not squeaky-clean avatars of sweetness and light either. Beyer is very clear: to enter the shamanic world is to enter a world shot through with sorcery, with harms as well as healings. Budding shamans either struggle with sorcerers or join the wickedness; in his fascinating discussion of psychic darts, which healers store in their bodies for a rainy day after extracting them from victims, Beyer explains why the dark side is actually an easier path to take. “Good” shamanism reveals itself to be an intensely ethical discipline, not only in relationship to the community of persons (human and otherwise), but to the darkness within. The shaman’s predicament is also grounded in social reality: a successful healer necessarily creates rivalry and envy, and when he fails at his healing task, necessarily creates paranoia and suspicion as well. This accounts for what Beyer calls the “social ambiguity of the shaman,” the fact that many of them are sneaky, unstable, and mistrustful. It’s a lonely path, anxious and ambiguous all the way down the line.

And the job has only gotten harder, even though there is more cash to be had and the global profile is at an all time high. Beyer closes the book with a pessimistic assessment of Amazonian shamanism’s future in a world where the younger generation would rather learn quick techniques from occult books than take on the ascetic rigors of the plant healing path. Beyer knows that conscientious gringos like himself will not fill the gap, especially when the general effect of the exploding Euro-North American interest in Amazonian shamanism is a spectral assault of dream darts soaked in naive assumptions and often narcissistic desires. Hopefully, Singing to the Plants will help us realize that one of the best cures for our own poisons is to learn how to hold them.

Read Erik’s interview with Stephan Beyer on Expanding Mind.

Francisco Montes Shuña, El Origén de la Ayahuasca y de la Chacruna (1998)

Don Francisco Montes Shuña is a traditional healer and visionary artist in the Upper Amazon, painting his ayahuasca visions with natural pigments on sheets of pounded bark. He is a founder of Sachamama Ethnobotanical Garden, a refuge for more than 1200 species of medicinal plants. The cover painting, El Origén de la Ayahuasca y de la Chacruna, depicts Pachamama, the earth mother, above, and Sachamama, the great boa, below, watching the ayahuasca vine and the chacruna plant being born from the corpse of the great shaman Aya, whose name means both death and soul.