Ronnie Pontiac: What is the American Renaissance as you have defined it for this Tarot deck?

Thea Wirsching: The term “American Renaissance” was the invention of literary critic F. O. Matthiessen in the 1940s. He identified Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville as the creators of an original American literature that flourished in the 1850s. Later, twentieth-century critics noted that Matthiessen’s list is composed solely of white men, and doesn’t include the author of the nineteenth-century’s most popular novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. So now, if you encounter the American Renaissance in a college classroom, you will probably be reading female writers like Emily Dickinson and black writers like Frederick Douglass, in addition to Matthiessen’s list of five.

As compared to the literary periods that preceded and succeeded it, American Renaissance literature is defined by philosophical inquiry, largesse of spirit, humanism, democratic ideals, and a reverence for nature. Essentially, it’s American Romanticism. The big lights of the preceding period were Washington Irving who was an Anglophile and James Fenimore Cooper who glorified colonialism and conquest, so they don’t make an appearance in The American Renaissance Tarot. And the big lights of the succeeding period, Henry James and Mark Twain, don’t appear in the project because their early work was not connected to the defining events of the American Renaissance: Transcendentalism and the movement to abolish slavery. I’ve seen the American Renaissance period described as the literature that appeared in the years 1830-1865, but for this project I’ve expanded the range to 1825-1875, to include early comers and late bloomers.

American Renaissance as a term was also unintentionally apt on Matthiessen’s part as a descriptor of the Neoplatonic and Hermetic aspects of the period that we see highlighted in the writing of Poe and Emerson. Just as the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century was a “rebirth” of Neoplatonic and Hermetic ideas that flowed from Ficino’s translations of ancient philosophical texts, so too was nineteenth-century Romanticism a product of the translation of these same texts into English by Thomas Taylor. So for me the term American Renaissance captures the Theosophical essence of the period that makes it so unique; we see the Transcendentalists experimenting with Neoplatonism, and the Hermetic understanding of microcosm and macrocosm underlies so much of the work of Whitman, Thoreau, and Melville. During the American Renaissance, many writers are engaged in discovering divinity within themselves, and it’s very exciting.

What’s the current status of the project?

I’ve written a manuscript that includes a detailed chapter about each Tarot card and how a particular American literary figure or story reflects that Tarot archetype. We just hit a milestone in that we’re three-quarters done with the art for the project. Creating the images winds up being an elaborate process when you’re trying to find the right balance between Tarot symbolism, literary specificity, historical accuracy, and of course – compelling art!

Our goal is to publish the cards and accompanying book though we don’t currently have a publisher. We’re badly in need of funds to power through the last leg of the illustration process, and we invite you to make a donation of any amount at our GoFundMe campaign. Publisher inquiries can be made directly to me, theawirsching@gmail.com

Why choose Tarot to explore the leading lights of the American Renaissance?

It’s funny you use that word “choose” because I don’t really feel like I chose the project, the project chose me! I was reading about the High Priestess in Jodorowsky’s book The Way of Tarot, and I received an image of Emily Dickinson, whose sibylline poetry, hidden body of work, virginity, reclusive nature, and habit of wearing white, all spoke so powerfully to me as the archetype of the High Priestess. Over three consecutive mornings I received a complete vision of an American literary Tarot, and which writers fit which archetypes.

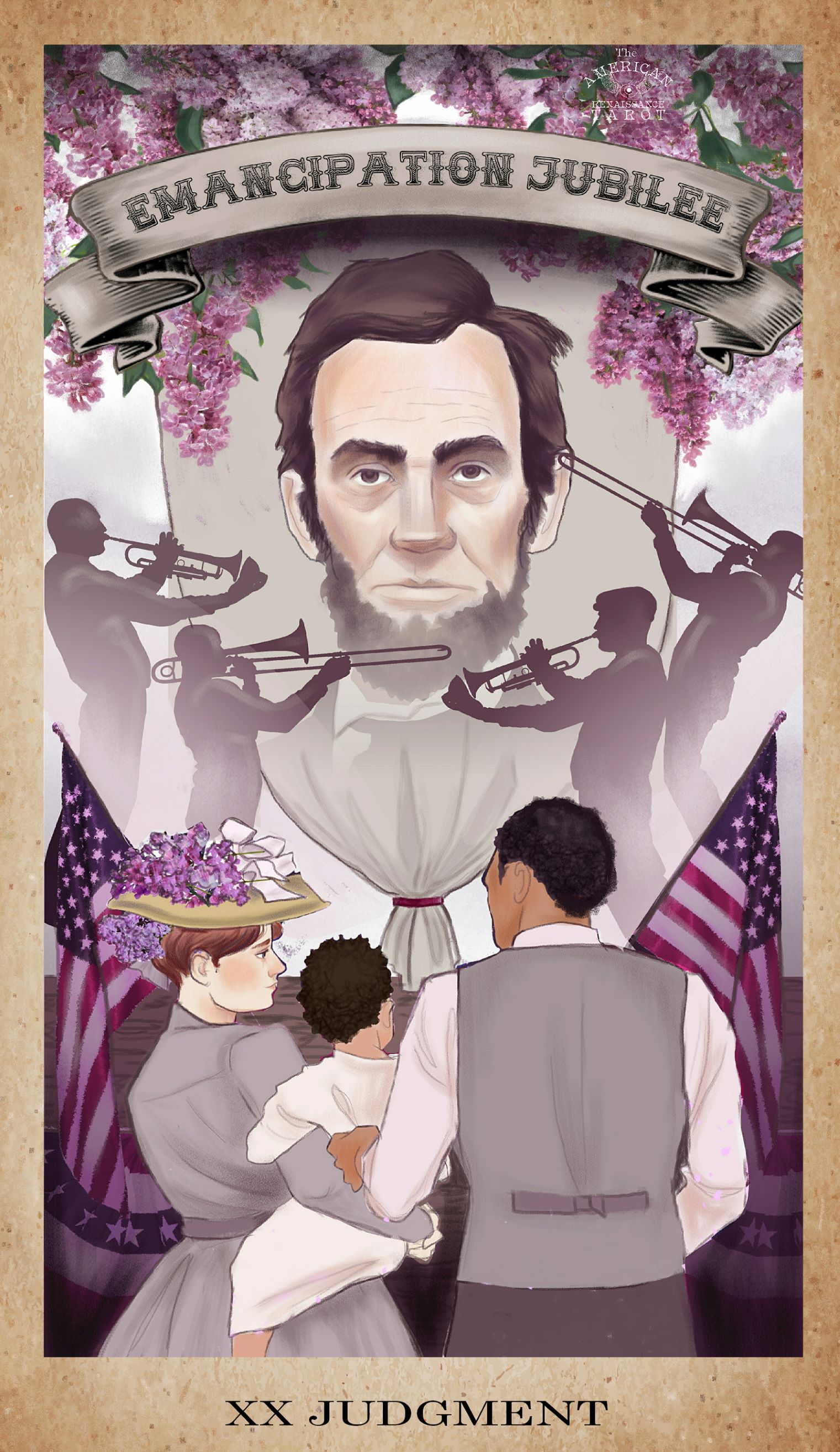

As to why I’m so committed to manifesting this vision in tangible form, however, I think it’s some combination of my American ancestry and a wish to salvage the promise of the American democratic experiment, which currently looks to be in ruins. I think it’s become fashionable to criticize and even to hate America, particularly in liberal and academic circles. Many of us are walking around in a lot of shame over who we are as a nation, and feel uncomfortable taking pride in a country that was built on the exploitation of African slaves and the genocide of indigenous people. And while I don’t think we should ever forget those horrific facts in our history, we’ve also thrown the baby out with the bathwater and rejected the knowledge that American culture has also been productive of incredible writers, thinkers, visionaries, and spiritual savants. I think collective shame keeps the left from embracing an educated patriotism that could help us turn the political tide; this project celebrates outspoken abolitionists such as Thoreau and Lydia Maria Child, successful black men like Frederick Douglass and Martin Delany, and philosophical innovators like Emerson. These Americans inspire pride and reverence in our history.

Tarot is a great medium for this goal because images have so much more immediacy than words. I would never expect to reach a high school student with a lofty book praising archival American writers, but with the image-sharing power of the internet, someone could happen upon one of our symbolic portraits of noble Americans and have his/her perspective changed within seconds. A 78-card Tarot deck is also the perfect medium for showcasing the diversity of American experience; The American Renaissance Tarot’s motley collection of political radicals, Spiritualists, explorers, feminists, sexual revolutionaries, and Afrocentric visionaries, gives us the opportunity to see our own times reflected in the nineteenth century. Too often the rich fabric of early American society is reduced to the tropes of repressive Christianity and virulent racism, and a Tarot deck is an excellent visual tool for restoring America’s historical heterogeneity to its representation.

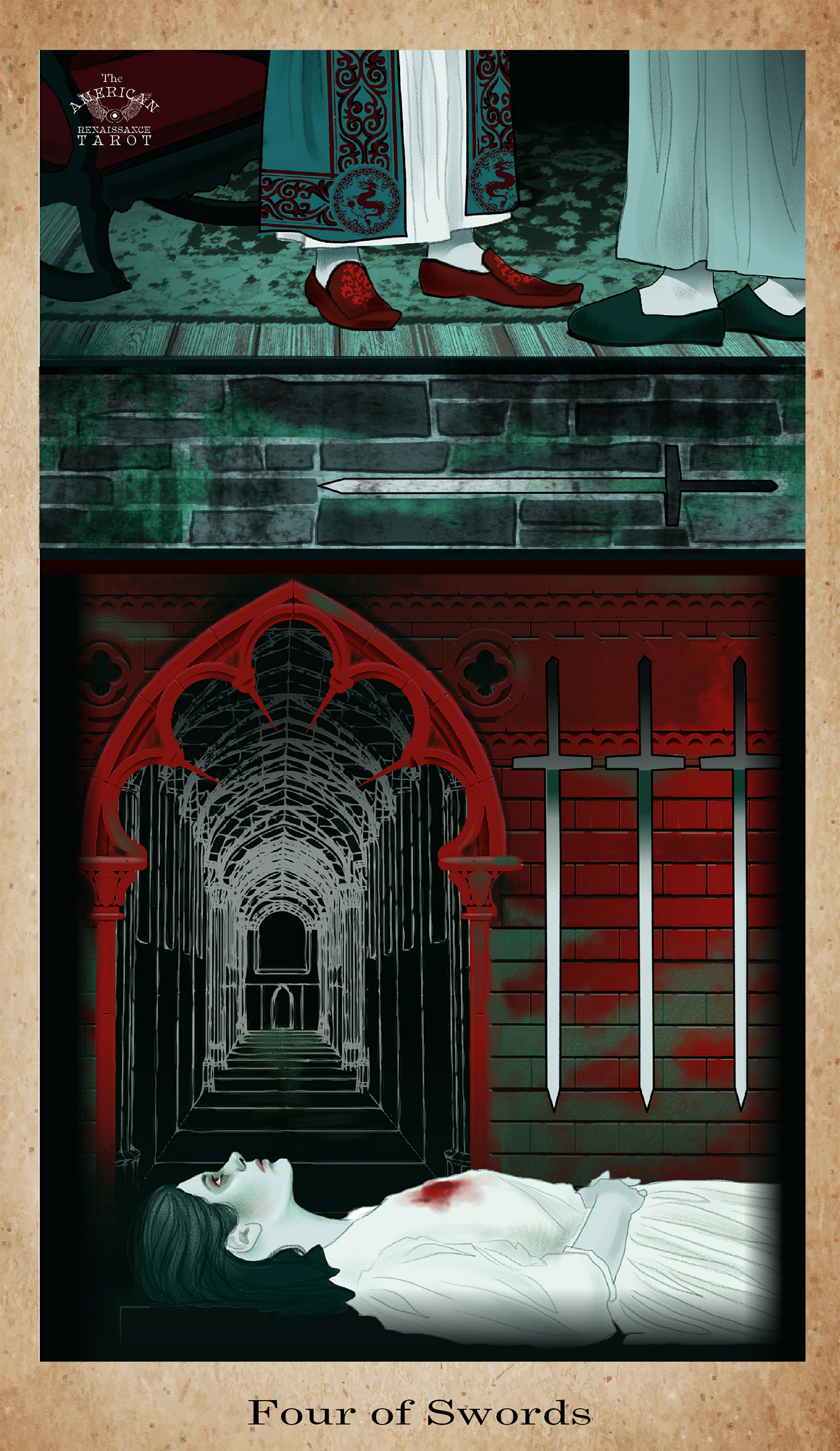

What inspired you to dedicate all the numbered Sword cards to Edgar Allan Poe?

Great question. Well a secret about the project is that the pip cards gave me a chance to get deep into the oeuvres of my favorite writers, and it’s certainly telling that there are more cards devoted to Poe in The American Renaissance Tarot than to any other writer. But I think the prevalence of Poe also has to do with how prescient he was in his literary themes. Today, films about murder, revenge, and abnormal psychology gross big at the box office, and detective shows are more popular than ever. Horror, science-fiction, and fantasy have gone mainstream, and Poe had a hand in the development of all these genres. So in many ways you could say that Poe is the most American writer, in that he had sophisticated insight into America’s shadow side. The African-American writer, Ishmael Reed, in his Civil War spoof novel, Flight to Canada, asks, “Why isn’t Edgar Allan Poe recognized as the principal biographer of that strange war?” It’s funny because Poe died in 1849, more than a decade before the war even started, but what I interpret Reed to mean is that Poe had a keen awareness of the violence and sadism that underlies the American psyche.

In the individual Tarot suits, I tried to group clusters of writers who had something in common for the court cards. For the Swords suit, usually associated with the Air element, I filled the court with writers who edited literary magazines: James Russell Lowell (Atlantic Monthly), Sarah Josepha Hale (Godey’s Lady’s Book), while Poe and his nemesis Rufus Griswold both had a stint editing Graham’s magazine, and others. The idea was to emphasize the explosion of print culture in the nineteenth century (Gemini), the cultivation of a national taste (Libra), and the technological innovations that made the rapid proliferation of periodicals possible (Aquarius). But when it came to the numbered cards in the Swords suit, Poe’s macabre vision always did more justice to the card themes than anything written by his compatriots in the Court of Swords. So they all went to him.

Beginning Tarot students are always distressed by how negative the Swords suit is – aren’t there any good cards? Do they all have to be so prickly? Poe was adept at putting his characters into “predicaments,” and predicaments lie at the heart of the Swords suit – a problem needs to be solved, how do I handle it? In our deck, the predicament might be a raven endlessly repeating the word “Nevermore,” your doppelganger stalking you and foiling your schemes, or your old friend forcing you to witness his complicated relationship with his undead sister in a moldy old house. These haunting scenarios, when re-imagined as Tarot cards, can suggest events in your own life that are causing confusion and pain.

Poe was also a legendary creator of hoaxes, and I wanted to exploit that trickster energy for the Swords suit. I was really happy that we were able to fit C. Auguste Dupin, Poe’s detective character, into the project, because he uses both cleverness and subterfuge to best his enemy in “The Purloined Letter,” our Seven of Swords. (Dupin, incidentally, appears to be the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes character, and Poe’s Dupin precedes Holmes by forty years.) To my mind, Poe’s talent, philosophy, and skill, reveal him to be a consummate genius – in a project devoted to writers he is the King of Swords, the writer of writers. But he was also a self-destructive, tragic figure who was too smart for his own good and prone to falling into his own traps. It’s hard to think of a better candidate to for representing the unceasing mental activity that characterizes the realm of Air.

What did you discover in your dissertation research about Poe and Hermeticism?

How much time do you have? Ha ha. Well originally I was troubled by the fact that the Transcendentalists took their name from Immanuel Kant (whom they only ever read in part and in bad translation) but their actual philosophies aligned more neatly with Neoplatonism than Transcendental Idealism. Poe famously hated the Transcendentalists and made several jabs at Emerson. I was immersed in reading Poe’s entire canon and was struck by his spiritualized Platonism, and kept scratching my head, trying to figure out how Poe perceived his philosophy to be counter to the Transcendentalists, when objectively he seemed to have a great deal in common with them.

It turned out to be a personal issue, of course; Poe was likely jealous of Emerson and maybe had some fair criticisms that Emerson’s language was often more pretty than precise. But on balance, they were both Transcendentalists, especially if we define the Transcendentalist movement as the resurgence of that Hermetic Neoplatonism that bubbles up periodically in Western culture, as it did in the Florentine Renaissance.

I became really obsessed with the ending of Poe’s novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, in which the narrator seems to experience a direct revelation of God, after which all the narrative continuity breaks off and the reader receives no further clarification. Pym is one of Poe’s greatest hoaxes; not only did he convince his nineteenth-century readers that the novel was a true autobiographical account by a man named Pym, he also set a series of traps for the conscientious reader, and I fell into all of them. I was so gratified to see Mat Johnson’s 2011 novel, Pym, about a college professor who becomes so obsessed with Poe’s novel that he charters a boat to the South Pole to test Pym’s enigmas for himself. Poe’s Pym invites obsessive attempts to figure it out – meanwhile the author probably had a good laugh to himself over all the blind alleys and meaningless clues he dispersed throughout the text.

Then I started exploring the idea that Pym was a Masonic novel, a novel that asks more questions than it answers and where all the meaning is necessarily self-defined. This line of thinking led me to understand Pym’s direct revelation of God as a type of Hermetic initiation, and upon further research I was just overwhelmed by all the Hermetic content in Poe’s oeuvre. Poe was so erudite and well-read, and it’s not clear if he read the Corpus Hermeticum itself or a synopsis of Hermetic ideas elsewhere, perhaps in Cudworth. But that Poe was attracted to Hermeticism is obvious; he was particularly fascinated by the idea that God and man, spirit and matter, are continuous, and that one is ultimately a reflection of the other. He seems to have been in the grips of some form of Hermetic revelation in the years before his death, when he wrote Eureka, a mystico-scientific cosmology and theory of everything which concludes that we are all self-creating gods. Eureka is also an eerily prescient book which predicts later benchmarks in scientific theory, such as the Big Bang and the theory of relativity. Poe died of a brain inflammation not long after publishing Eureka, and we pay homage to Poe’s “Big Bang” of Hermetic revelation in our Ten of Swords card.

What was Poe’s influence on Aleister Crowley?

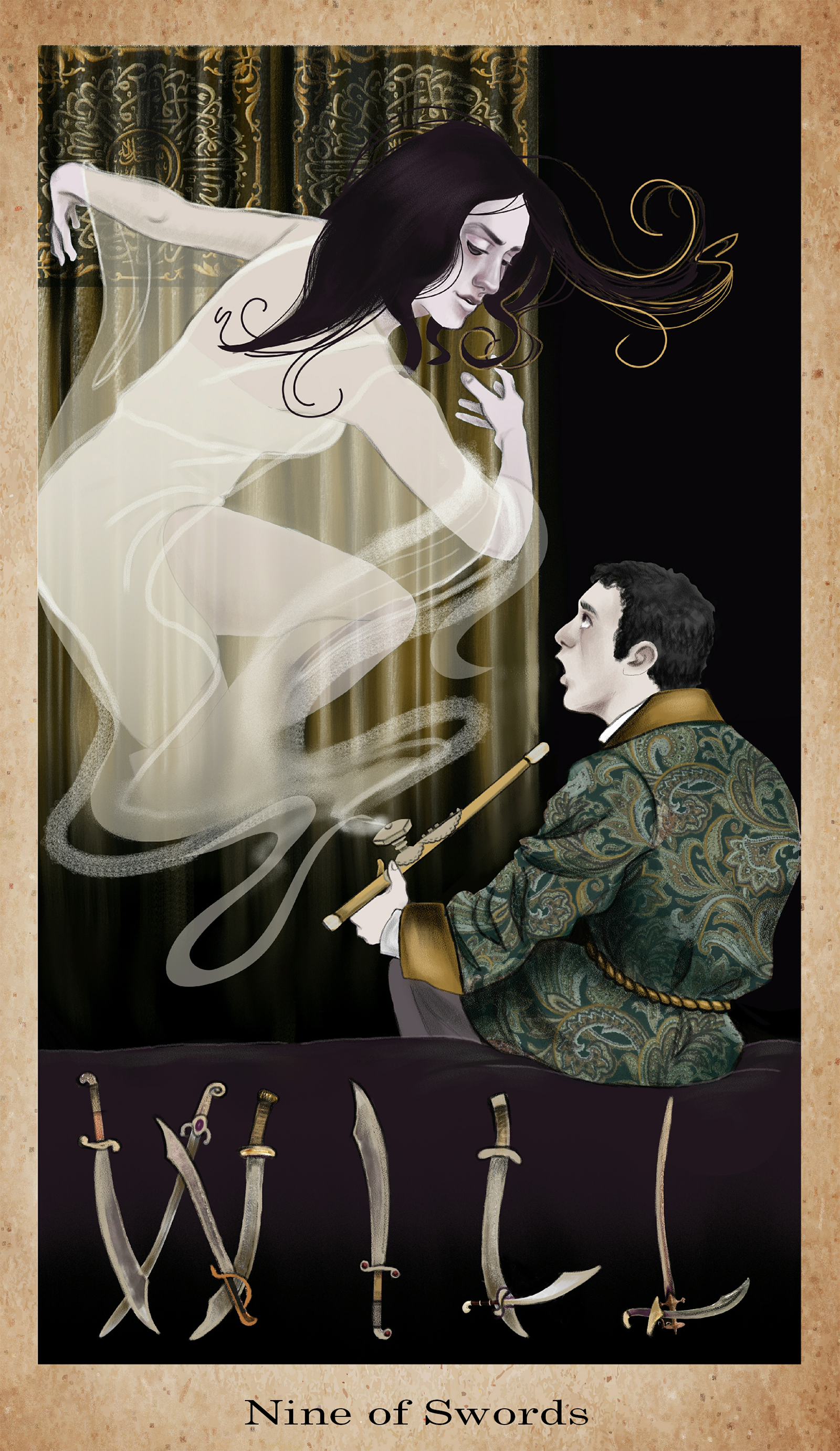

Haha! Wow do I love this question. This is one of those lines of inquiry that sounds like it would have a really spicy answer but boils down in practice to literary sleuthing. Essentially Crowley quotes one of Poe’s made-up quotes at the beginning of his novel, Diary of a Drug Fiend (1922). Crowley thinks he’s quoting Joseph Glanvill but he’s not, he’s quoting Poe. A.E. Waite does the same thing in his 1891 book Occult Sciences, quoting Poe via Glanvill without knowing it. So I guess technically we could imagine that Crowley lifted the quote from Waite instead of encountering it where it originally appeared, Poe’s 1838 story, “Ligeia.” But it’s just a whole lot more fun to assume that Crowley read “Ligeia,” Poe’s story about achieving metempsychosis through mastering the will. In fact it’s very likely.

Here’s the quote Poe wrote but attributed to Glanvill:

And the will therein lieth, which dieth not. Who knoweth the mysteries of the will, with its vigor? For God is but a great will pervading all things by nature of its intentness. Man doth not yield himself to the angels, nor unto death utterly, save only through the weakness of his feeble will.

What follows is a wild story about the narrator and his wife, Ligeia, and their occult studies. Ligeia attempts to fend off death with her “gigantic will.” She is initially unsuccessful and dies, and the narrator rather unaccountably marries again. He then sets up a pentagonal chamber outfitted with satanic flourishes and Egyptian sarcophagi. Soon his new wife begins to decline, and a metempsychosis takes place – the second wife’s blond hair is magically replaced by the black tresses and eyes of Ligeia! Ligeia beats the conqueror worm after all.

Given Crowley’s emphasis on the concept of magical will, it’s certainly exciting to find evidence that Crowley was taking inspiration from fictional sources like Poe. Tellingly, Crowley makes reference to Edward Bulwer-Lytton in Diary of a Drug Fiend as well, and Bulwer-Lytton’s occult fiction was a huge influence on Blavatsky’s early Theosophical books. One of the overarching arguments of my dissertation is that there is a back-and-forth borrowing between occult texts and fictional texts stretching back many centuries. As to where Poe learned a theory of magical will I can’t say – Eliphas Levi post-dates him so we have to look back even earlier. Maybe Poe himself is one of the great creative intelligences behind Thelema. We can certainly credit Poe with a number of other important twentieth-century trends – why not this one?

What inspired you to pick Lydia Maria Child for the Strength card?

Oh she’s just wonderful. Child is one of those archival writers that almost no one would encounter today unless you were taking a graduate course in a special topic in early American literature. But she had a fifty-year long career as a writer and activist in nineteenth-century America, and she is probably one of the only social commentators of the times that you can read today without cringing. What I mean is that racism was so universal in the nineteenth century that you almost have to expect it as a matter of course whenever you’re perusing American Renaissance literature. There are plenty of passages in Emerson that stop me cold, when he starts getting all self-consciously white and male. Emerson was also a latecomer to the abolitionist party. Child however sacrificed her hard-won popularity as a writer to publish a book called An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans called Africans – in 1833! You can get a lot of the tone of the book from the title – it’s not called The Problem of the Negro and Where to Place Him or something like that, and she comes right out and says “In Favor.” She’s in favor of equal rights and opportunities and giving people the chance to prove themselves, whether she’s talking about African-Americans, Native Americans, women, or religious minorities. That’s who Child was. She’s so progressive that so much of what she’s written sounds like it was written last year instead of 175 years ago!

But because this is a visual project, I knew I wouldn’t be able to get anyone excited about a serious-looking white lady with a center part. We ran into this problem with the Temperance card a bit – the gap between the powerhouse that Elizabeth Cady Stanton was as a thinker and the prosaic image of a dowdy mother in a bonnet. So on the Strength card we went with a Native American theme in reference to the numerous manifestoes that Child wrote in defense of Indian rights. What the Tarot’s Strength card means to me is an ability to maintain compassion in the face of evil and oppression. That was Child to a T. She kept writing and kept fighting but did it in a less confrontational and polarizing way than her male counterparts. I also like how the card image suggests the continuance of Native American religious practices in spite of the bloody history of coloniaztion.

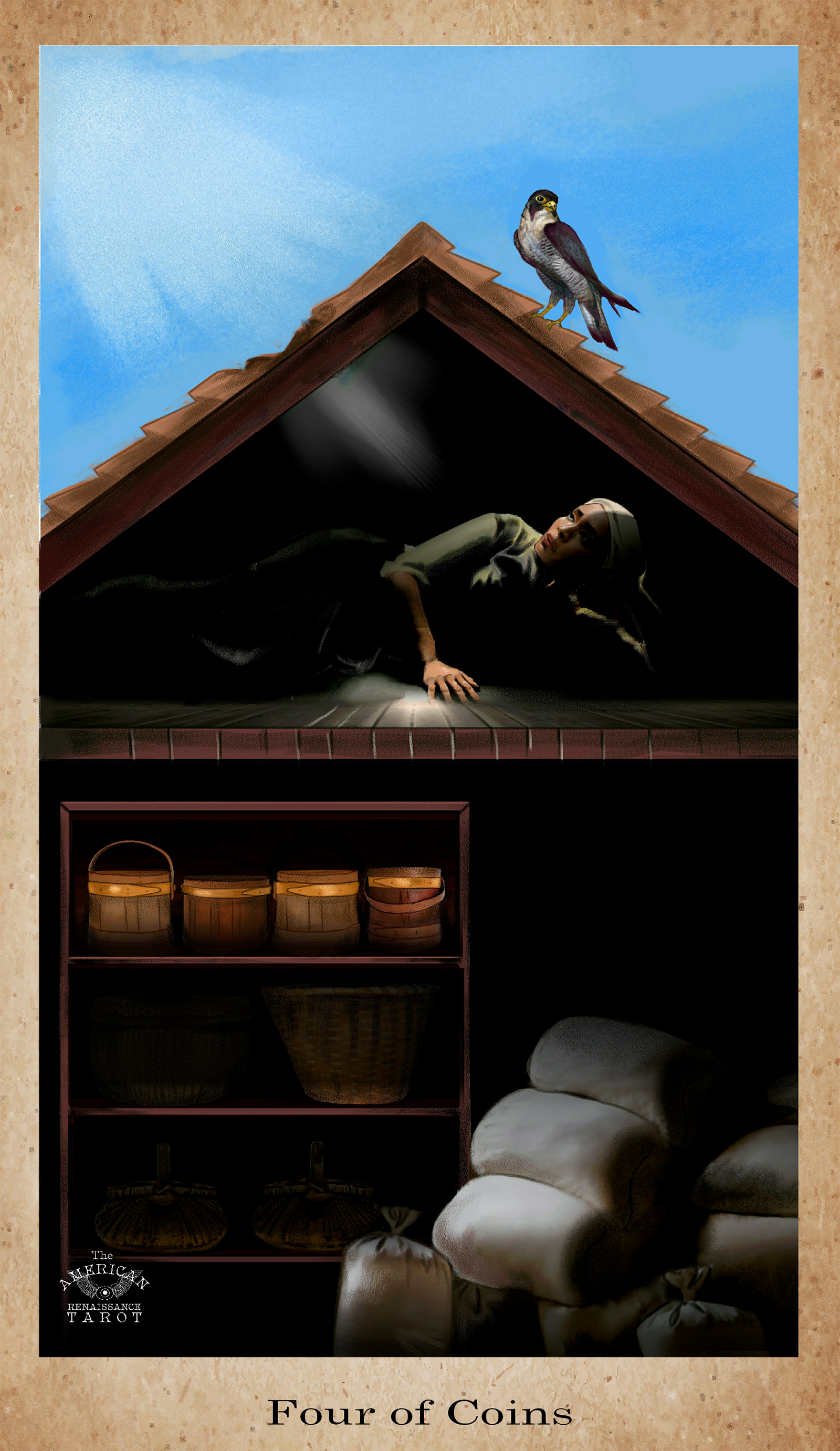

What inspired you to relate the Coin cards to Frederick Douglass?

I could talk about this for hours! Well again, the pip cards are where I was able to really have fun and exercise the depth of my literary knowledge. You’ll notice that there’s only one Emerson card, one Whitman card, and one Thoreau card, but six cards devoted to Douglass. That was intentional, in that I wanted the Major Arcana to have this special status and not be diluted by spreading the material too thin. But in the stories told by the various suits I was able to do more nuance, less archetype, and so the meanings come across as sharper and more coherent because they’re not as iconic or symbolic.

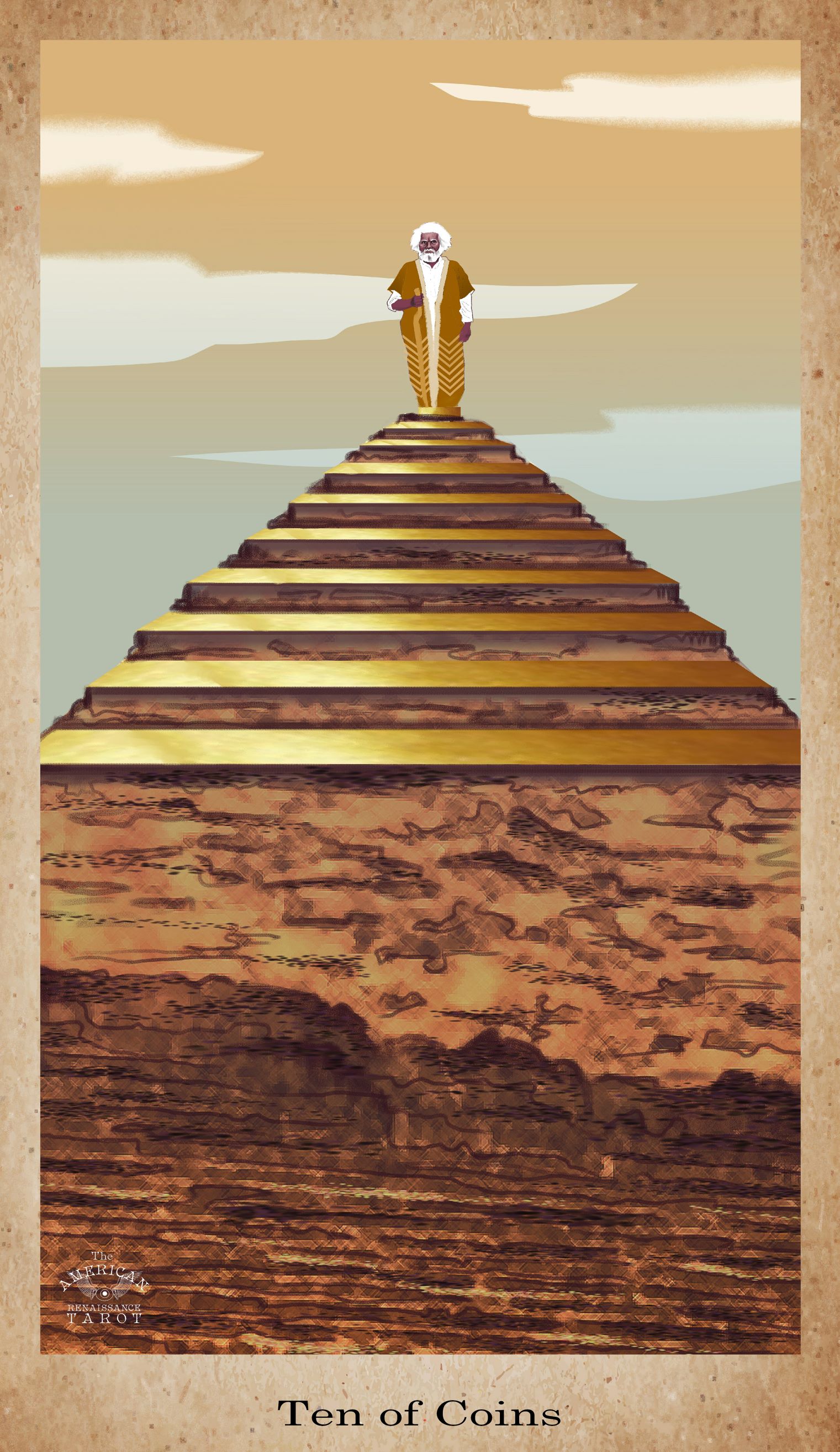

I think if you’ve read Douglass there’s just no question that he’s going to be the King of something in a Tarot deck. A lot of my academic friends who are not familiar with Tarot asked me why he couldn’t be a “major” figure and I would sort of laugh to myself and say, “Don’t you know who the King of Coins is?” Coins represent practical life in the Tarot – money, survival. The four black writers in our Court of Coins were necessarily concerned with survival not because they lacked philosophical imaginations like Melville or allegorical imaginations like Hawthorne, but because American society prevented them from being concerned with anything else. For Douglass to be born a slave and transform himself into a man by resisting his slave-master, and then plot a successful escape and make a name for himself as a brilliant orator, then write several riveting autobiographies and go on to positions of prominence in government while maintaining the status of a leader of his people … I mean, what have you done lately? He’s just so inspiring. A fun little factoid I discovered was that Douglass was a wealthy landowner at the end of his life, and his holdings far exceeded the estates of our other Kings, Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville, put together. So he’s a true King of Coins in that he made a Franklinesque rise to the top of the social hierarchy, not even owning himself when he was born and then growing to become the unofficial leader of the African-American people in his times.

I featured African-American writers exclusively in the Coins suit because this suit shows growth and development, the endless struggle to make the stubborn Earth yield up its treasures. So I love that the Coins suit begins with “Sandy’s root” on the Ace, the little bit of Conjure that helped Douglass to fight for his right to be free when he was still a slave, and ends with him standing on top of the Great Pyramid of Giza as an old man on the Ten of Coins. This is something he really did when he was seventy years old! So visually the Coins suit shows that arc, from humble roots to the apex of human ingenuity. We also show Martin Delany in his officer’s uniform on the Eight of Coins and Harriet Jacobs holding her freedom papers on the Nine of Coins, other ways in which African-Americans were able to escape the oppression of racism and come into positions of ownership and status.

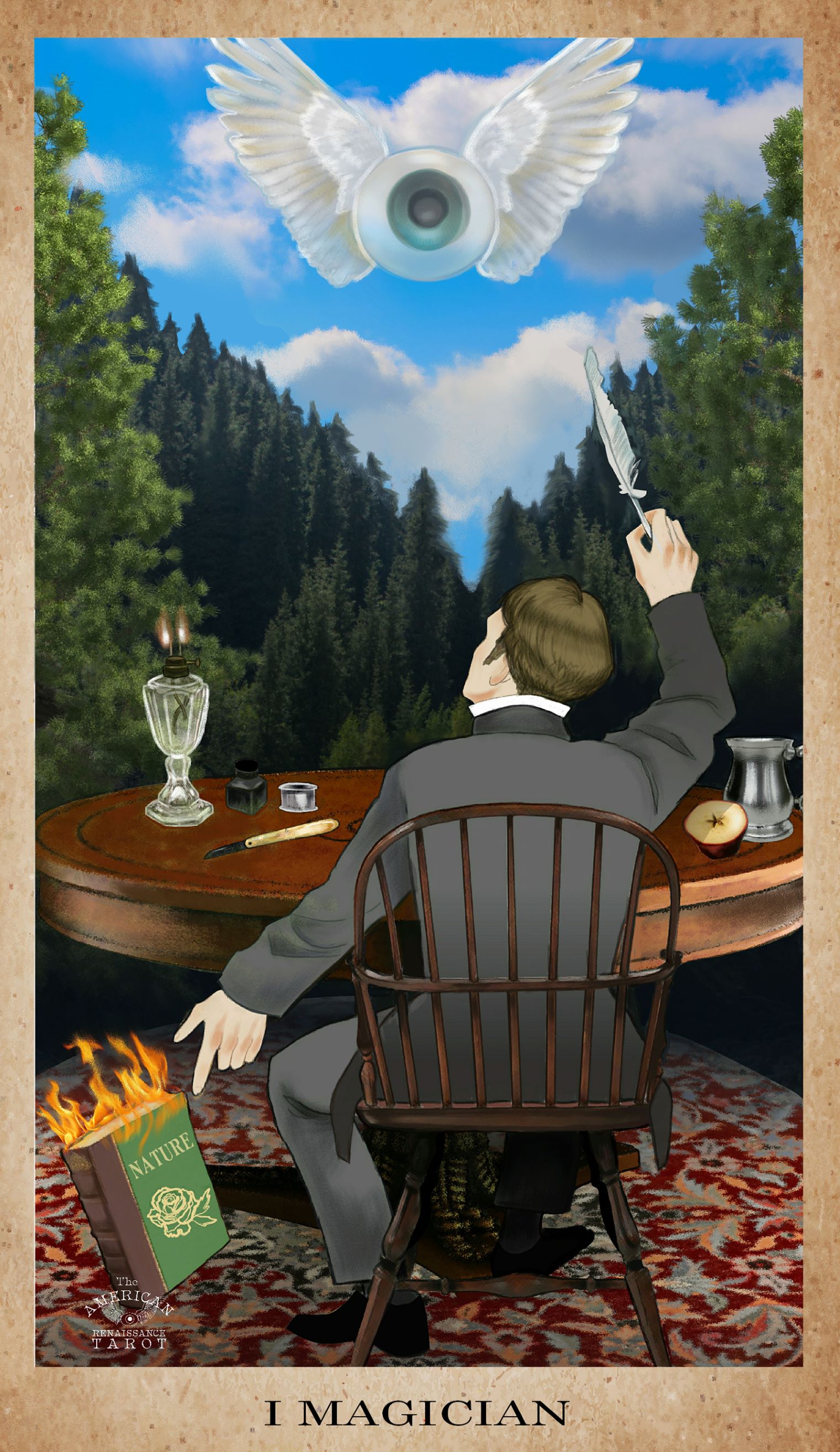

What inspired you to choose Emerson for the Magician card?

Well now it seems like a no-brainer but I did wrestle with it for a bit. One way I could answer honestly is to say that he really didn’t fit anywhere else. I mean he could be the Emperor because of the reach of his thought on nineteenth-century America, or the Pope because so many people viewed him as a quasi-religious authority. Emerson could fit on the Sun or the Star or the World card. But that would mean leaving a vacancy in the Magician card that no one else could adequately fill.

I know you’re a big fan of Catherine Albanese’s book, A Republic of Mind and Spirit, and something she gets into there is the prevalence of mental magic in America that was due in large part to the primacy of Emerson. We see it flower later in the century in the rise of the New Thought movement. I think what Emerson gave to his audience was permission to think for themselves and to break with the religious oppression of the past. It’s worth pointing out that Emerson couldn’t even make it as a Unitarian! So he was for all intents and purposes a secular authority who argued that there could still be meaning and purpose and dignity in life without religion. I tend to think of him as the first modern self-help guru because he encouraged people to think about thinking and reflect upon the self-creating power of thought, and how the individual’s mind is akin to the mind of God. That’s pretty heady stuff for a populace still recovering from the psychological trauma of Calvinism! The reason we didn’t put Emerson’s face in the deck is that I don’t think he would have wanted his legacy to become the unthinking hero worship that we see today – the whole point of his project is to “build, therefore, your own world.”

No one is ever going to turn up evidence that Emerson was a ceremonial magician because for him, the mind is enough, according to him you don’t need rituals or tools. He exemplifies the Magician archetype because he advocated for action and self-worth, as appears most clearly in his famous essay, “Self-Reliance.” He was a Gemini and extremely well-read, and I’m not convinced he ever settled on a philosophy other than what we might cover with the umbrella term, Transcendentalism. But as he says in the same essay, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” His project is not about abstract philosophical perfection but rather about becoming conscious of yourself as a thinking being, and directing the force of your godlike mind to noble action. Emerson is the authorizing figure behind so many of our Major Arcana personalities, such as Whitman, Fuller, and Thoreau, that I think the Magician moniker is merited!

How did you choose the artist for this deck?

After I wrote the project I was really stuck because I like so many styles of art but didn’t have the artistic vocabulary to describe what appealed to me. But I knew what I didn’t like – contemporary digital-collage Tarots don’t work for me at all and I knew I didn’t want the hyper-embroidered fantasy-scapes that are so common in the Tarot world today. I thought a lot about Pamela Colman Smith, the artist for the iconic Rider-Waite deck, and how her drawings are so simple but have been so enduring. So I knew I was looking for an illustrator as opposed to a fine artist.

I kept drawing the Page of Cups during my search and had the intuition that the artist would be a young woman. I wish I could turn this into a more richly symbolic and enigmatic tale but the truth is that I was shopping for shower curtains on Society Six when I found Celeste Pille! I just fell in love with her style and there were a couple of key factors in her work that made me move forward in pitching her on the project. One, I couldn’t tell you exactly how she does this but her portraits of women are totally non-sexualized. They’re adorable and whimsical and compelling and somber and all these other things but she never resorts to using sex to make the image work. It struck me initially as an exceedingly rare quality in an illustrator, to not turn women into hourglass cartoons or to go the other direction and make them defiantly ugly. Her women are just women, uncorrupted by the male gaze. It still amazes me.

The other factor that impressed me is that she didn’t seem to have any hang-ups around illustrating black people. I think when white people illustrate people of color there can be all this unconscious “othering” that goes on, even with the best of intentions. But I didn’t see any of that in her work. I remember seeing her portrait of Beyoncé and one of her “grown up” Nickelodeon characters and thinking she could pull off the really sensitive racial material that the deck was going to require.

I pitched her and the rest is history! Of course, she turned out to be a politically progressive feminist so it’s been a pretty effortless collaboration; she’s an absolute joy to work with. I really love her clean graphic style, which makes the card meanings so much more readily apparent. I think of Celeste as taking a modern twist on the Pamela Colman Smith tradition, in that she hand-sketches her portraits but colors them in digitally.

Have any particular Tarot decks had special influence on you?

Oh sure, I grew up with several copies of the 1970s Tarot of the Witches in the house, the one that was featured in the James Bond film Live and Let Die. My Mom was an art teacher and she had all this occult ephemera lying around for her high school students to copy, but she wasn’t connected to the meaning of any of it. She was also a serious antique collector and I think that has had a huge unconscious shaping influence on the look of our project. I have kind of a sixth sense for nineteenth-century material culture because I grew up in a house that had everything from antique bellows and stable equipment to vintage medicine bottles and shaving kits. When I was an infant my Mom pushed me around in an enormous Victorian baby carriage! I’m sure it left some kind of psychic residue.

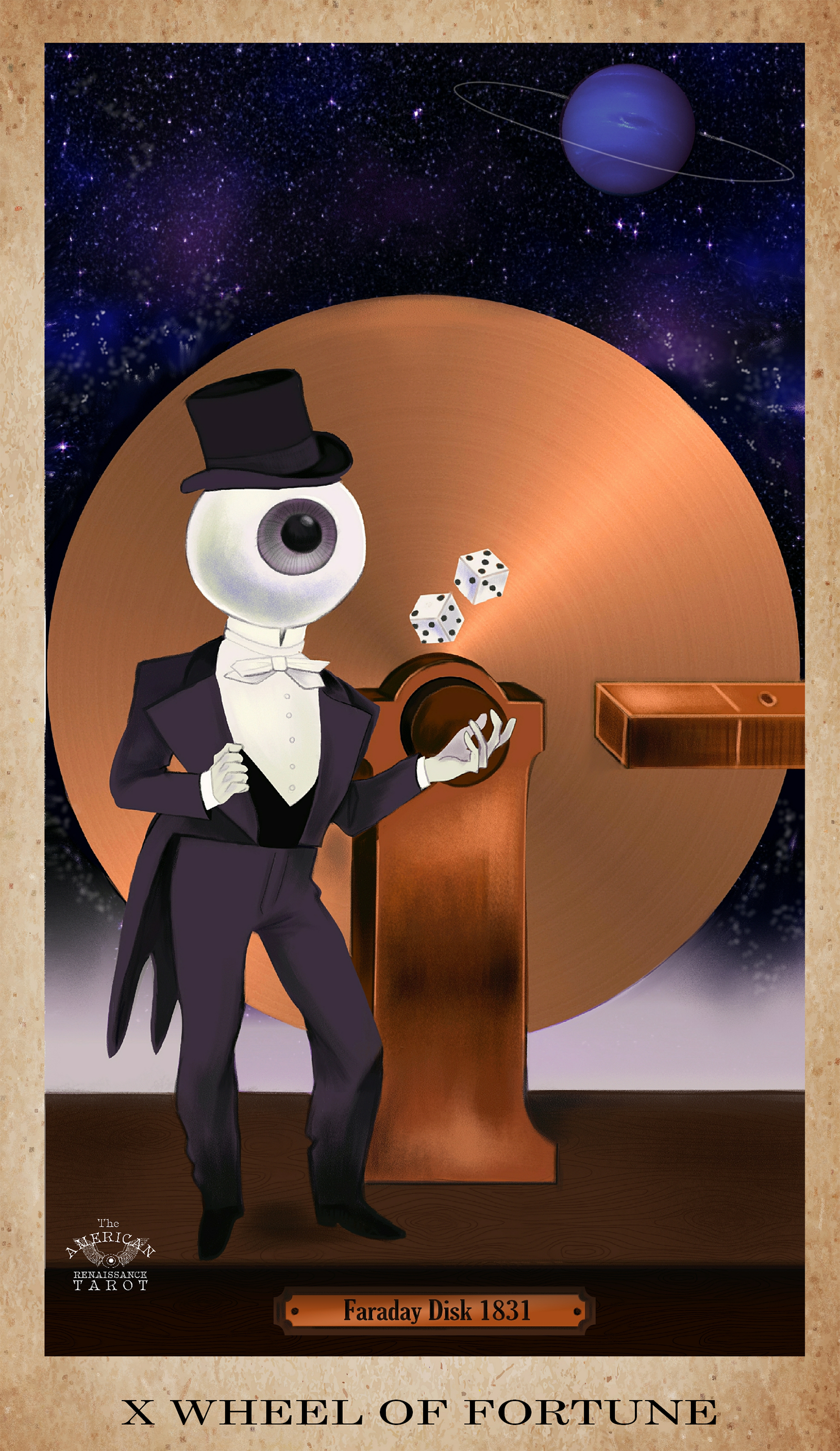

I think the deck that really inspired this project though was the Steampunk Tarot by Barbara Moore and Aly Fell. My husband bought it for me on a lark because we’d had a Steampunk wedding and the Two of Cups reminded him of our nuptials. But when I started using it, I became really captivated by the mood and the clothing. I found that the images spoke to me so much more powerfully than the Rider-Waite images because the time period they depicted was not as distant. The Steampunk Tarot gave me a way to imagine an archetypal past that also contained machines, by depicting sophisticated modes of transit, high-tech weaponry, communication systems, clocks, and factory production all set against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution. Our lives are so intimately mediated by machines now that the mid-nineteenth century, the period just before the technological revolutions that ushered in the Information Age, seems like a quaint and innocent epoch by comparison. Of course our project is more focused on the Transcendentalist’s reverence for Nature than on technology, but the most labor-intensive aspect of creating the images has been researching the state of technology in the 1840s, 50s, and 60s, because it changed so rapidly. Writing technology accelerated from quills to fountain pens to typewriters in less than a century – it’s dizzying. We put a double-wicked whale-oil lamp on Emerson’s desk to represent the 1830s and by the end of the century there were electric lights – just phenomenal. We used our Wheel of Fortune card to make the point that so much of what we experience in life is determined by the quality of the technology to which we are exposed.

What inspired you to pick Paschal Beverly Randolph for the Lovers’ card? Having studied him academically how do you see his place in the history of American Metaphysical Religion and American Renaissance literature?

I think I struggled more over the Lover card than I did any other Major Arcana excepting the Fool … Randolph was an obvious choice for me, but he’s very much an archival figure and I knew his marginality would raise eyebrows placed alongside all of these major figures. However, we could argue that Emily Dickinson’s secret cache of poetry was not published until the 1890s, and Melville’s small contemporary fame did not grow to epic proportions until the twentieth century. In other words, I think there’s still time for Randolph to evolve into a major figure of the nineteenth-century literary scene in the eyes of modern critics. Just in the last fifty years we’ve seen an explosion of new material enter the canon of American literature, as the academy has been forced to shed its ancient habit of failing to take women and minorities seriously as writers. But even with this new dispensation, Randolph remains controversial; his status as a sex doctor, occultist, and hashish enthusiast, to say nothing of his flexible racial identifications, makes him a difficult figure to rescue from the archive. But with the foot that Occult Studies seems to have lodged in the academy’s door in recent years – who knows? Perhaps Randolph’s academic redemption will come.

Jodorowsky names this card the Lover, singular, as opposed to the Lovers, plural, and in that spirit I think Randolph fits the archetype perfectly. The Lover can signal that experience of deep affinity that we have when falling in love, but it can also be applied more broadly to any scenario in which we’re being called to clarify our values and choices. What I love about Randolph’s career is that he so consistently did the wrong thing according to the values of every group he was attached to, but the right thing in his own eyes. He pleased himself, and that’s one of the best ways to sum up what the Lover archetype is all about.

Randolph’s 1863 autobiographical novel Ravalette is the first work of science-fiction and fantasy by an African-American in addition to being only the fifth or so novel published by an African-American in the United States. It’s also the first vampire novel written by an American. Protagonist “Beverly” must quest in search of a woman born of an atavistic race in order to undo an ancient curse, and so we cast the woman, Evlambea, in the role of the presiding angel that is traditional to the Lover card. Randolph seems to have enjoyed lifelong spiritual communication with his African mother who passed when he was just a boy, and so we used his description of her as a “Madagascan Queen” as our inspiration for the woman on the left. We used an image of his white wife Kate as our inspiration for the woman on the right. We wanted to convey with this card that Randolph never identified strictly as black or white, preferring to selectively identify as either when it suited him, or even to invoke his mixed-race ancestry as a kind of superpower. What intrigues me about this approach to racial identity is how upset it makes people, both today and in the racially fraught nineteenth century. But was Randolph really failing to heed the Lover’s admonition to choose, when he publicly waffled over his blackness? Or was he pleasing himself by choosing instead to flout social expectations around racial identification? I rather love that he re-imagined himself as an amalgam of seven pure bloodstreams so that he could defy the insult of traditional racial categorizations; his colleagues in the Spiritualist community called him the “little octoroon.”

A big challenge of casting the Major Arcana was having to choose the “ultimate” representative of a nineteenth-century movement. So in representing nineteenth-century feminism, do I go with Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Susan B. Anthony? I put Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story on the Justice card although many people told me the obvious choice there was John Marshall. In almost all the cases that demanded I choose among strong candidates for a particular Tarot archetype, I gave the card to the figure with the more impressive literary legacy. Cady Stanton wrote Anthony’s speeches. Story elucidated Marshall’s decisions in his popular and influential treatises on Constitutional law. So that’s a long way of saying that I used Randolph to represent a diverse nineteenth-century movement called “Free Love,” because he wrote so extensively on sexual alchemy. Victoria Woodhull may have been Free Love’s more famous icon, but Randolph wrote its manuals. (I know a number of people might rush to counter that Randolph disclaimed Free Love as a movement, which is true, but today we use “Free Love” as an umbrella term to encompass the many forms of sexual radicalism that coalesced in the nineteenth century.)

As far as Randolph’s influence on American religion, I think it’s been massive. I argue this point in my chapter in Brill’s Esotericism in African American Religious Experience (written under my academic name). One religion scholar claims Randolph preceded Blavatsky in the turn away from passive mediumship and toward active communication with ascended masters, and another scholar argues that Aleister Crowley mined Randolph’s writing for his innovative sex magic. Blavatsky’s Theosophical system and Crowley’s ceremonial magic have been the two biggest influences on the rise of the twentieth-century New Age, and Randolph had a hand in the evolution of the thought of both Blavatsky and Crowley. I’d say that’s quite a legacy.

How does American Metaphysical Religion relate to The American Renaissance Tarot?

Well I think it’s admirable that Catherine Albanese made the attempt to subsume all of America’s aberrations from the religious mainstream under one heading, but I’m not sure I find the term “American Metaphysical Religion” entirely satisfying. It’s useful, just not that satisfying, because it leaves out so many of the real differences between, say, Conjure, American Freemasonry, and Theosophy, just as a start. In general I would say that the publication of Albanese’s book A Republic of Mind and Spirit was a watershed moment as far as defending alternative traditions like these as religion. That’s huge. In my graduate career I continually encountered the problem that the occult was not considered a legitimate field of study in any discipline, and it was shocking to discover that Western Hermeticism did not have a natural home in religious studies. I had to hunt for it across field as diverse as medieval literature and history of science, classics, chemistry, art history, and astronomy. I remember being floored when I discovered that Joscelyn Godwin was a professor of music. The mere fact of Albanese placing esoteric American religions in historical relationship to one another in the same resource marks an invaluable contribution to a new field that I believe is still taking shape.

I think my passion for this Tarot project came out of a non-academic impulse, in that I’m not claiming commonality across diverse traditions so much as I’m arguing for their contiguity. When I look at mid-nineteenth century America, I see the reflection of twenty-first-century America. There were root doctors, sex radicals, Rosicrucians, feminists, Spiritualists, Unitarians, Evangelicals, Mormons, socialists, black nationalists, homosexuals, Nature worshippers, and devotees of the Goddess. What I want The American Renaissance Tarot to foster is a feeling of identification with the American past, instead of that instinctual recoil. There were also racists and robber barons in our shared American history, just as there are today, but why do we focus on those villains so exclusively? Then as now, gross moral violations were often sanctioned by the government and defended as “natural rights,” but the law flowed down to regular folk from entrenched systems of power that seemed impossible to change. It’s a tragic waste to convict our collective American ancestry of cruelty and stupidity when in reality there were so many bright shining lights.

Of course this project is very personal to me on many levels, but one thing I’ll share out of my own metaphysical experience is a consciousness of how much pain Americans are in on account of having so little in the way of ancestral traditions. The fundamental ideology of America is the break with the past: throwing off the shackles of Great Britain and inventing a new government; being kidnapped from your home country and forced into chattel slavery in a new land; the immigrant experience and the demands of assimilation; being forced from your native land and having your indigenous traditions educated out of you and into oblivion. I felt the pain of broken ancestry acutely growing up, believing my father’s estranged Southern family to be “white trash” and my mother’s German-Bohemian ancestors to have preserved nothing of value that I could claim as a legacy, not even a family recipe.

I’ve since learned how to reclaim my family line with ancestor work, but I think initially my attraction to American literature had something to do with my longing for ancestors. This will sound odd, but so much crystallized for me when I read my first slave narrative in my sophomore year of college. It was such a revelation to me – it seemed like the most compelling literature in the world and I couldn’t believe I hadn’t even heard of slave narratives before. The text was Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs, and I felt – seen – by the text in a way that I had never seen my own life reflected in the work of Jane Austen or Henry James, for example. Jacobs lived in a constant state of crisis because of the absolute power her owners had to make decisions about her family and her future. Her master was sexually harassing her so she had to use her sexuality strategically, and take a white lover in order to gain protection from her master’s abuse. I don’t want to be misinterpreted here – I’m not saying I “understand” slavery because I relate to Jacobs in the text, it was more like one of those magical moments that the humanities can facilitate, in that I saw myself reflected in the life of a mixed-race woman who was born two hundred years ago. I too grew up in a house of sexual abuse and harassment. Jacobs was telling my story even though she came before me.

I’ll give Jeff Kripal credit for the idea that reading is a deeply metaphysical act which melds you mind to mind with a writer who may be dead as far as the body, but whose words live on in your apperception of them. As I started to read deeply in the canon of early American literature, I adopted more and more “ancestors” in the form of writers whom I revered, because they gave me a sense of place and of the past that hadn’t come down to me through my family, or through the “great deeds of great men” tenor of the American history classes I experienced growing up. Ultimately this was a very grounding endeavor. I now know who I am. I am an American.

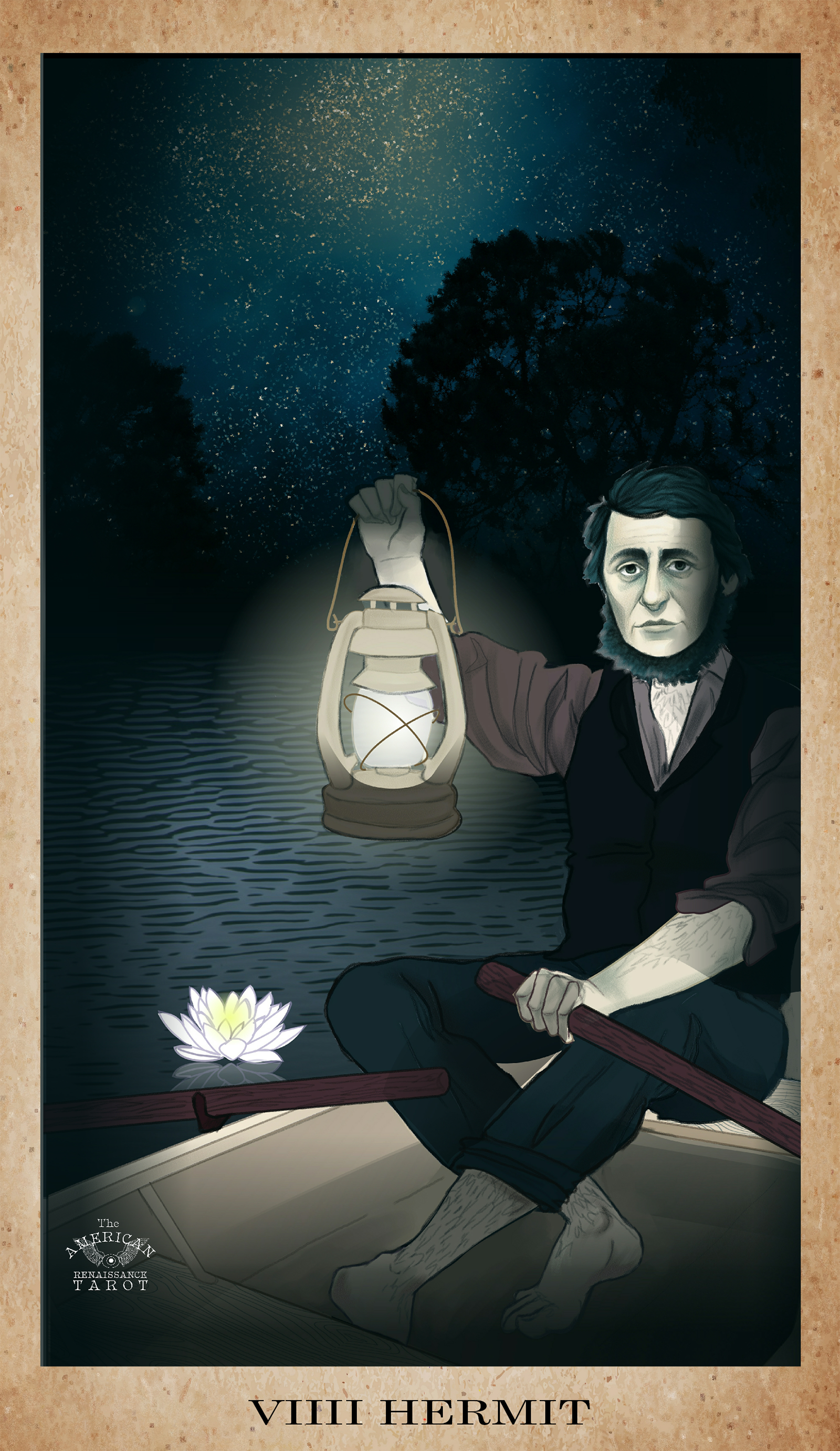

So to circle back to your original question – The American Renaissance Tarot is a celebration of contiguous developments in esoteric American religion. Albanese has credited Thoreau with originating a tradition called “American Nature Religion,” and he’s our Hermit. George Lippard was a serious Rosicrucian and he’s our Knight of Wands. Margaret Fuller looked to ancient goddesses for psychological liberation from oppression, and she’s our Empress. I made William Ellery Channing our Star card because his bold Unitarian vision inspired Emerson’s Transcendentalism. Joseph Smith the Mormon mystic is our Fool. I used the influential Protestant Henry Ward Beecher for the Pope card because he took the brimstone out of the Congregationalist tradition, a pivotal development within Christianity which paved the way for the later rise of Evangelicalism. The sisters who popularized Spiritualism appear on our Moon card. Martin Delany revered the ancient religions of Ethiopia and Egypt as a Prince Hall Freemason, and he’s our Knight of Coins. And on and on.

But you certainly don’t have to be a religion historian to use and enjoy our project. Hawthorne was an atheist and looked for redemption in human love, and there are three cards in the Cups suit derived from Hawthorne’s stories that showcase the psychological hell of the Puritan’s religion. Melville was something of a tortured agnostic, perhaps a Gnostic, and the Wands cards as a collection deal with the redemptive power of making noble existential responses to the crushing pettiness of life in a fallen world. Douglass also does not seem to have had much use for religion, and the Coins cards are focused on applying hard work and practical solutions to life’s problems. Edgar Allan Poe was a Platonist and an adherent of Mesmerism, but he was also smart enough to know that the mind is the great deceiver. So the Swords cards are an ode to the mind’s disturbing ability to orchestrate beauty and terror indiscriminately.

Anything else you’d like to add?

I’m so grateful for the opportunity to share this project on Reality Sandwich! As William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.” Promoting awareness of a noble epoch in American history in which people of diverse backgrounds came together to fight for liberty and justice for all, can transform the way we view the future of our country. It is my hope that The American Renaissance Tarot will provide the mythic material to inspire Americans to take pride in their roots, thereby awakening the consciousness that we have something of great value in these United States, something magical and precious that merits rescuing from the current threat of fascism and tyranny.