The following is excerpted from Who Am I? Yoga, Psychedelics, and the Quest for Enlightenment by Allowaha. The book is due to be published in the Summer of 2016. You can pre-order a signed first edition of the book here.

“Soma, soma, devamritam, parama jyoti, namo, namah”.

“To soma, nectar of the gods, who reveals the divine light, salutations, again salutations!”

“a ápāma sómam amŕtā abhūmâganma jyótir ávidāma devân c kíṃ nūnám asmân kṛṇavad árātiḥ kím u dhūrtír amṛta mártyasya”

“We have drunk Soma and become immortal;

we have attained the light the Gods discovered.

Now what may foeman’s malice do to harm us?

What, O Immortal, mortal man’s deception?”

—The Rigveda (8.48.3, tr. Griffith)

“…The Vedas derive, more than from any other single identifiable source, from Soma. Would it not be useful, then, to know what Soma was? Not particularly, India herself seems to have answered, judging from her scholars’ lack of interest in identifying the lost plant.”

—Huston Smith

“The Soma sacrifice was the focal point of the Vedic religion. Indeed, if one accepts the point of view that the whole of Indian mystical practice from the Upanishads through the more mechanical methods of yoga is merely an attempt to recapture the vision granted by the Soma plant, then the nature of that vision – and of the plant – underlies the whole of Indian religion, and everything of a mystical nature within that religion is pertinent to the identity of the plant.”

—Wendy Doniger

“I was told she was manifesting amrit, nectar, from her feet…”

I first was drawn into the yoga fold during the Spring and Summer of 1996. During that time I had the rare opportunity to meet no less than four truly remarkable women saints from India. These encounters were due to the gentle, but insistent prodding of a colleague in my religious studies graduate program. An Indologist-in-training, who recognized that I was on a spiritual quest and decided I was ready to meet the masters. It was a wild ride for a guy who just two years earlier had been a born-again Orthodox Jew in Jerusalem! But now I actually was ready. There was a clear sense in which I took all four women to be my teachers. However, it was with only one of them, Śri Karunamayi, that I developed a more traditional guru-disciple relationship, traveling to see her in India no less than five times in as many years.

The basic hagiographical account of Śri Karunamayi’s life I knew from both verbal stories and writings about her . Prior to her birth in 1958, Śri Karunamayi’s mother went to see Ramana Maharishi, revered both East and West as the greatest sage of 20th century India. At their meeting, the great sage told her she would soon give birth to an incarnation of the Divine Mother.

Indeed, from birth onward Śri Karunamyi did display signs that the great seer’s prediction was true. Her deeply compassionate nature inspired the name “Karunamayi,” or “Goddess of Compassion.”

A major turning point came in her first year of college, when she began meditating for longer and longer periods in her family’s worship room. Finally, one day she locked herself in the room for an entire month,. emerging, according to her family, clearly transformed. With her mother’s blessing, the young saint-in-the-making left college and lived for the next 12 years in a remote forest outside of Bangalore “absorbed in meditation for hours, days, or even weeks at a time.” At the conclusion of her tapasya (austerities) in the early 1990s, a temple was built for the now recognized saint in Bangalore, and she began offering regular worship services there.

When I met Śri Karunamayi in the mid-‘90s, she was just beginning to establish a presence in the States. The first time I went to see her was, ironically enough, in a synagogue in Philadelphia built by Frank Lloyd Wright. At first, I didn’t know what to make of the diminutive, plump woman I soon came to call “Amma” (a word for “Mother” in South India); she seemed so soft-spoken and unassuming. I knew she was gifted. I just wasn’t feeling especially called to follow her.

Nevertheless, my colleague-mentor strongly felt that Śri Karunamayi had IT, and as I trusted her opinion completely, I went along for the ride. In 1998 this ride took me to Amma’s temple ashram in Bangalore, India, which I visited daily for nearly a month.

While I was certainly amazed and touched by my teacher’s loving, motherly presence, if I was going to devote my life to her service the skeptic in me, the critical analyst developed over years of academic training and Torah study, was always searching for more “proof.” As with Ram Dass and the Westerners who entered the orbit of Neem Karoli Baba, that proof came for me mainly in the form of the unconditional love and compassion I felt from this obviously saintly being, and often within myself when around her.

But I wanted –I needed — more. If Amma truly was omniscient, I wanted to experience that she was. If she really could do miracles, I wanted to see one. If she could inspire profound meditation, I wanted to feel that. I got glimpses and heard other people’s miraculous stories, but I wanted more than just glimpses, more than just stories. I needed to see/hear/feel these things for myself. (I realize now this was my problem, not her’s, yet it was what it was.)

Now one siddhi, or yogic power, that Śri Karunamayi is said to have is the ability to manifest various sacred substances from her feet. I actually was in her Temple in Bangalore during the Navaratri Festival when she began to produce the red vermillion powder known as kumkum that many Indian women place on their foreheads. At the moment this was happening, however, I was absorbed in meditation, and moments later when I finally sensed the commotion all around me, all of the Indians in the room had already rushed to the front and I couldn’t actually catch a glimpse of the “feat.” When Amma left the room and the crowd simmered down, I did see the powder settled in heaps around where Amma’s feet would have been. On another occasion, I came into the room only after it happened to witness the same sight.

This all had been preceded back in the States by another devotee friend giddily relating how on the 7th day of a 9 day meditation retreat with Amma in India, he and the others were aroused from their meditations to witness amrit (also, devamritam; cognate with the Greek “ambrosia”), the “nectar of the gods,” pouring from Amma’s feet. They even got to taste it. He said it was essentially the same stuff that miraculously comes out of a wall at Sai Baba’s ashram, Whitefield, just outside of Bangalore, and he gave me some to sample. But as for the actual production of it, I never got a chance to see this, and again, though I was extremely impressed by Amma in so many ways beyond such yogic powers, the living proof continued to elude me.

Śri Karunamayi

I bring all of this up partly because, as we will see, this amrit is very pertinent to the discussion of Soma that follows.

Soma, Why & Wherefore?

By this time, most of us have heard the word “Soma,” whether via Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, by the steroid of that name (aka, Carisoprodol), or simply because it has entered the lexicon to mean a hallucinogenic substance. So it’s at least on the periphery of the collective consciousness, as it was with me until I discovered that there has actually been some controversy over the actual identity of the Vedic Soma.

Curiously, while Śri Karunamayi would discourse at length on the ancient Vedic way of life, she rarely spoke of Soma. Soma is first spoken of in the Vedic texts as both a deva, or deity/god, no less – the most revered of the Hindu pantheon — and an intoxicating drink (among other things).

Perhaps this omission is due to the fact that the term Soma,is such a complex one, and the exact identity of the Soma brew so elusive, Or perhaps Amma was only doling out what she felt we, her “little children,” could grasp. Whatever the case may be, Soma has remained one of the most hotly debated subject among Western scholars and researchers of entheogens (Huston Smith’s preferred designation), and many lay users of psychedelics are interested and well-versed in this debate. For those new to this subject, let’s begin the discussion by considering the core of the controversy.

First it seems appropriate to ask: Why should we care about Soma at all? Why is its identity all that important, anyway? Isn’t Soma a part of ancient history that has no bearing on our lives now?

Yes, and no.

No, because given the widly-ranging and diverse views on what Soma is, a definitive answer as to its true identity seems highly unlikely; and in any case, we also have our own modern “Somas”,– the plan-based psychoactive substances that are the subject of this book — to consider. But yes, too, and for several reasons…

First, if it could be shown that ancient religions, such as “Hinduism” (traditionally referred to as Sanatana Dharma, or “Eternal Religion”), were inspired by ingesting sacred plant concoctions, then this would have a profound effect on our understanding of religion generally, and the Hindu/Sanatana Dharma tradition, very specifically.

Second, if we could get a better idea of what Soma was, and determine if it still exists today or could be re-produced, we might then make use of it as a technology or tool that would better inform our understanding of the Yoga tradition.

Finally, a deeper study of the Vedas and its “Soma,” regardless of what it is or was, can only help to enlarge our understanding of this time-honored spiritual tradition.

There is another reason to probe the identity of Soma. Soma is currently part of a broader debate regarding whether Western scholarship has been fair and accurate in its descriptions and analyses of India’s origins, history, and culture. In the case of our mysterious substance, the issue in particular is over the extent to which R. Gordon Wasson’s thesis, which claims that Soma was a brew concocted from the Amanita muscaria mushroom (also known as “The Fly Agaric”), is to be privileged over the views of those who speak from within an “authentic” Indian tradition.

Wasson’s Thesis

- Gordon Wasson was a banker who also was the founding father of the field of “ethnomycology”, the study of the cultural use of mushrooms. In 1927 Wasson happened upon some wild mushrooms on his honeymoon with his wife, Valentina Pavlovna Guercken. They published their first book, Mushrooms, Russia, and History in 1957, the same year that they became the first westerners to participate in the Mazatec sacred mushroom ritual with the now legendary shaman, Maria Sabina. This ritual involves the ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms (widely known as “Magic Mushrooms”), and the resulting ecstatic voyage Wasson was taken on deeply inspired him to continue to immerse himself in the fields of ethnomycological and entheogenic studies.

Wasson’s work had a profound impact on many subsequent users of psychedelics. An article he and his wife penned for Life magazine that year, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” was the catalyst for the subsequent psychedelic quests of many diverse and notable people, including Aldous Huxley, Anthony Russo, Michael, Bowen, Timothy Leary, and Richard Alpert.

Although eventually Leary became best known as the “High Priest of LSD,” it was his participation in the Mazatec magic mushroom ritual in 1960 that inspired his Harvard research.

Leary famously commented that he “learned more about my brain and its possibilities, and more about psychology in the five hours after taking these mushrooms, than I had in the preceding fifteen years of studying and doing research in psychology.” A remarkable statement, for sure. Although Leary later became known for his dramatic and hyperbolic declarations, in this case, I suggest, he was not exaggerating.

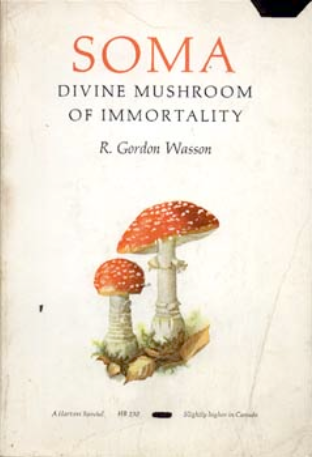

Wasson’s Famous Limited-Edition Book on Soma

I first was exposed to Wasson’s research via Huston Smith’s work, Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals (Tarcher, 2000). Smith presents Wasson’s thesis and then summarizes his main arguments, adding that despite the recent controversy surrounding them, they are still “the strongest in the field.”

These arguments essentially boil down to Wasson’s thesis that Amanita muscaria best fits the descriptions of Soma in the Vedas, in regard to its genus, color, shape, geographical location, and psychoactive properties. Another interesting fact that makes Wasson’s argument stronger is found in a passage in the Vedas suggesting that Soma was also drunk via the urine. This is because its psychoactive properties survive metabolic processing. This practice was also known to have been used in other cultures, too, most notably the shamans of Siberia, about whom their is interesting speculation that their drinking Amanita muscaria through the urine of reindeer may have been the real origin of the Santa Claus myth.

On a first reading of Smith’s presentation of Wasson’s work, and knowing something of the Vedas and Vedic science, I was impressed by Wasson’s research, but not persuaded beyond a reasonable doubt about his thesis. Wasson had just not provided any truly convincing proof that Soma was a mushroom, let alone Amanita muscaria. It just seemed like so much scholarly conjecture.

Yet I was given pause by the number of top scholars supporting his thesis, including the well-regarded Indologist Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, as well as Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann & Christian Ratsch. Could all of these great scholars be mistaken?

Perhaps. After all, as Smith himself acknowledged, much was to be gained from discovering the original identity of Soma, first and foremost a permanent place in the history of scholarship. Smith also added that “most ranking scholars had abandoned the quest as hopeless,” a statement which should tell us something about how difficult the task was.

Moreover, because Wasson was such a mycophile, might there have been an element, even if only just a tad, of attempting to fit the evidence to a prior and preconceived conclusion? Needless to say, perhaps, Wasson has had his critics.

Contra Wasson:

If Wasson’s thesis found moderate support among Western scholars, including Smith, there has been far less sympathy toward his views from inside the tradition. When I queried American-born sadhu Baba Rampuri, who has been living among the psychedelic-savvy Naga Babas for the past 40 years, he confirmed what I already felt, although he took things quite a bit further:

“Wasson paid a couple of Sanskrit scholars (incl. Wendy O’Flaherity) to find amanita in the Vedas. His hypothesis is ridiculous. It makes no sense whatsoever to people, like myself, who actually know about these things. I WISH it were true!! It would be great! But all this research and writing was done by people who spent very little if any time in India, and people who have never even met a shaman, let alone took a trip with one. Wasson was very generous with Maria Sabina (he was a banker, you know), and he may have been very well informed about Mexican shamans, but certainly not Indian ones. I met him once, and he was a gentleman. But I’m afraid he and many others, especially today, miss the point. It’s not the chemical formulas – it’s the deities. And Dr. Hofmann knew this well, it just took him many years to come to grips with his first meeting with LSD.”

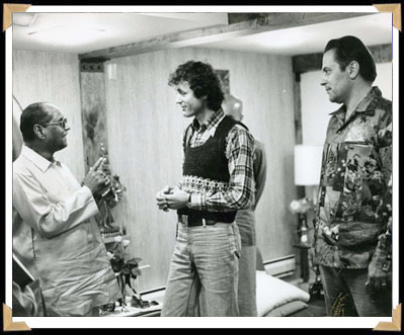

Baba Rampuri at the 2008 World Psychedelic Forum (sharing words with Alex Grey)

Rampuri’s deeper concern here is essentially the same as the one he stressed at the 2008 World Psychedelic Forum in Basel, Switzerland, namely: How is it really possible for Western scholars to speak with any authority about a culture that is not their own and which they have not even experienced in any depth from within its fold?

Indeed, turning this question back on myself: How is it possible for me to write about yoga, and yoga’s view of psychoactive plants from outside of the Indian tradition? To this, I can only answer that by letting the twain of speakers from both East and West meet within these pages I am simply attempting to let both sides speak for themselves and thereby allow the reader to reach their own conclusions.

Today there are Western-born vedic scholars, like Dr. David Frawley (Vamadeva Shastri), who do know Indian culture intimately and are very highly regarded within both worlds. Frawley has also been one of the most vociferous spokespeople for the view that Western scholarship has greatly misunderstood and misrepresented Indian culture and tradition.

Dr. Frawley’s view is that Soma is an umbrella term for many substances, including even water. His thesis is that it probably referred to several plants that were used sacramentally in Vedic times and afterwards. He sums up his research in this area as follows:

“My view – based upon more than thirty years of study of the Vedas in the original Sanskrit, as well as related Ayurvedic literature – is that the Soma plant was not simply one plant, though there may have been one primary Soma plant in certain times and places, but several plants, sometimes a plant mixture and more generally it refers to the sacred usage of plants. Soma is mentioned as existing in all plants (RV X.97.7) and many different types of Soma are indicated, some requiring elaborate preparations. Water itself, particularly that of the Himalayan rivers, is a kind of Soma (RV VII.49.4). In Vedic thought, for every form of Agni or Fire, there is also a form of Soma. In this regard, there are Somas throughout the universe. Agni and Soma are the Vedic equivalents of yin and yang in Chinese thought…Soma is also connected with marijuana, suggesting that mind-altering plants were regarded as different types of Soma.”

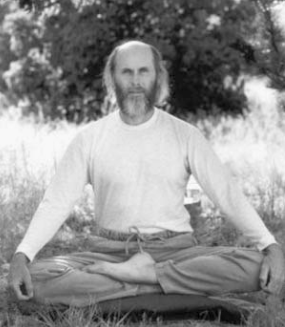

Dr. David Frawley

While Frawley does not rule out the possibility that Amanita muscaria may have been used after the Vedic period, he holds that “the main Rig Vedic Somas were probably certain reed grasses, some of which do have nervine and nutritive properties.” This, of course, would certainly argue against Wasson’s notion that Amanita muscaria was The Soma of the Vedas.

Another highly regarded American-born Indologist and Ayurvedic physician, Dr. Robert Svoboda, has also suggested that Wasson’s thesis misses the mark. In Aghora, Dr. Svoboda’s fascinating exploration of Tantra, the author quotes his guru, Swami Vimalananda, as having said:

” The Rishis [great yogi seers] used to take soma, which is a type of leafless creeper. Some people today think soma was the poisonous mushroom Amanita muscaria, but that was also merely a substitute for the real thing. Only the Rishis know what the true soma is, because only they can see it. It is invisible to everyone else.”

So, among those who are deeply acquainted with Hindu culture, spirituality, and scholarship, it appears that the claim that Soma was Amanita muscaria, as Wasson and others stated, simply does not hold water. Rampuri, Frawely, and Svoboda have all leveled arguments against such a claim, as have others from within the Indian tradition. Additionally, certain Western researchers outside of mainstream academic circles have challenged Wasson on this point, most notably the late Terence McKenna.

Amanita…or Psilocybin?

Not long after reading Smith and Wasson, I discovered McKenna’s 1992 work, Food of the Gods, and found very persuasive his critique of Wasson’s thesis that Soma was Amanita muscaria. Of course, being Terence McKenna, the Psilocybe champion bar none, he was willing to acknowledge that Wasson was “brilliant in advancing the notion that a mushroom of some sort was implicated in the Soma mystery,” he just wasn’t convinced that mushroom was Amanita! It was Psilocybe Cubensis (aka “Magic Mushrooms”), of course.

McKenna’s main points are as follows: 1) Amanita muscaria does not produce “a reliable ecstatic experience…the rapturous visionary ecstasy that inspired the Vedas…could not have possibly been caused by Amanita muscaria” ; 2) Wasson himself considered the possibility that Soma was in fact Stropharia cubensis (Psilocybe cubensis), raising but not answering his own question: “Is Stropharia cubensis responsible for the elevation of the cow to a sacred status?” Which is a question that also came to my mind during my first experience with magic mushrooms. Other mycophiles have suggested this idea to me as well, in addition to the idea that Krishna’s famous theophany in the 11th chapter of the Bhagavad Gita appears to bear strong resemblance to a psychedelic experience. McKenna suggests it was Wasson’s aversion to the Hippie cult of psilocybin, including “self-styled psychiatrists” that he himself inspired, that would not allow him to accept such a conclusion; 3) Connected with this last point, Wasson appears to have avoided the obvious fact that Soma in the Vedas seems to be inextricably linked to cattle, particularly the bull, which makes sense for Stropharia cubensis because it grows on dung, but not for Amanita. Mckenna doesn’t say it, but I would answer Wasson’s question by suggesting that it would certainly help explain the sacredness of the cow in India! 4) Perhaps the most damning evidence McKenna brings is a letter Wasson wrote to him which expressed doubt about his own thesis and seemed to favor Stropharia cubensis, a possibility which, McKenna notes, Wasson eventually contradicted.

Even given the amount of conjecture involved, McKenna certainly presents a very strong argument against Wasson’s thesis, if not a completely compelling case in favor of Stropharia cubensis.

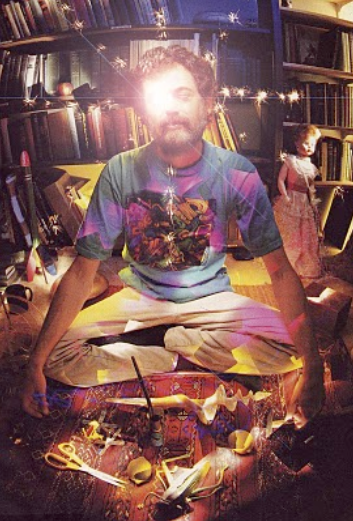

Terence McKenna

The tentative nature of all of these conjectures aside, what I find most compelling in Food of the Gods, is McKenna’s overarching theory of the stages through which the human relationship to the Divine via Soma has been degraded over time.

He proposes that there are four distinct stages to this devolution: 1) In the first stage, there was a substitute made for the original Soma, a substitute which is still a psychoactive plant, but a less potent one, such as Ephedra; 2) In the next stage of devolution, due perhaps to climactic changes, a completely inactive plant is substituted for the active one; 3) In the third stage, there are no plants whatsoever, and in their place are merely “esoteric teachings and dogma, rituals, stress on lineages, gestures, and cosmogonic diagrams,” as we find in today’s major world religions; 4) And finally, we have reached the fourth stage today in our modern secular West. A state in which we find ourselves in a “complete abandonment of even the pretense of remembering the felt experience of the mystery.”

While it is doubtful that such a hypothesis would carry much weight in mainstream academic circles, let alone those sympathetic to the Hindu tradition, McKenna does raise some interesting points. Key among them are questions as to why no one knows the original identity of the Vedic Soma, and why the use of soma-like psychoactive substances in India has largely been downgraded to the status of “Left-Handed Tantra”? The latter is considered a less-than-pure path to God, and is a province occupied primarily by Shaivite sadhus, wandering yogis who are followers of Shiva.

Could it be that the ritual ingestion of sacred plant extracts was what formed the basis of some major current world religions? Perhaps this may seem like a conspiracy theory, or revisionist history, but for a moment, let’s entertain the possibility that we have been robbed of our spiritual birthright by doctrines and dogmas created and enforced by a priestly caste; rules and regulations that diminish and degrade the once sacred value of these natural plant admixtures. Is it possible that we have surrendered our power to this priestly caste? A human institution that has secured spiritual and physical power for itself at the expense of an opiate-intoxicated, and thus numbed, citizenry?

I hope it is clear that these are questions form the heart of this book. Here we are seeking answers to questions such as:

~ Is a human Guru or other intermediary really necessary, or can sacred plant medicine be as good, if not better, as a teacher?

~How is plant Samadhi the same or different than the Samadhi that comes through spiritual practices such as meditation, and can we say that one is higher or lower, worse or better than the other?

~ Do psychoactive plant medicines “level the playing field,” as McKenna and others have suggested, allowing each and every individual to find their own spiritual truth within themselves?

Such questions are directly connected to this whole debate over Soma. I touch upon them here in an attempt to make the reader aware of the deeper connections involved between yoga-induced expanded consciousness, and expanded consciousness achieved through the use of plant extracts.

McKenna’s Critique

An entire book could be written on McKenna alone in regard to the above questions, particularly relating to the period just prior to his life-changing trip to the Amazon basin with his brother Dennis in 1971. For, like so many young seekers of his generation, McKenna had first journeyed to Mother India in search of the divine.

Yet unlike many spirit-questers, McKenna came away disappointed. He expressed his feelings about India candidly on a number of occasions, not least his critique at the outset of his work Food of the Gods:

“I had traveled India in search of the miraculous. I had visited its temples and ashrams, its jungles and mountain retreats. But Yoga, a lifetime calling, the obsession of a disciplined and ascetic few, was not sufficient to carry me to the inner landscapes that I sought.

” I learned in India that religion, in all times an places where the luminous flame of the spirit had guttered low, is not more than a hustle. Religion in India stares from world-weary eyes familiar with four millennia of priestcraft. Modern Hindu India to me was both an antithesis and a fitting prelude to the nearly archaic shamanism that I found in the lower Rio Putomayo of Colombia when I arrived there to begin studying the shamanic use of hallucinogenic plants.””

On another occasion, McKenna put it like this:

“[Psychedelics] are democratic. They work for Joe Ordinary. And I am Joe Ordinary. I can’t go and sweep up around the ashram for eighteen years or some rigmarole like that.”

This seems to have been a recurring theme for McKenna. Interviewing Ram Dass in the early ‘90s, he made a very similar point:

“The idea is not to come up with something that the best among us can make hay with, but a democratic…something that addresses the species. The thing that seemed to me so important about the psychedelic experience was that it happened to me…So I assumed that I am a very ordinary person, therefore if it happened to me, it could happen to anyone, and that’s unquestionable.”

It’s not clear if McKenna’s issue was with the degradation of Indian religion, per se, or more his own, and by extension, most humans’ unwillingness to submit to the long, hard discipline of a spiritual practice. He seemed to be conceding that the discipline of yoga alone could take you there, but why work that hard if we don’t need to? So McKenna was asking: Why take the ox cart when the hyper-space shuttle is available?” His concern was not just personal, but global. In the above interview, McKenna asks Ram Dass “Do you think this [the return back to Source consciousness] can be done without psychedelics fast enough to have an impact on the global situation?”

This dialogue between these two psychedelic pioneers is particularly interesting because of McKenna’s skepticism of India’s traditional religious doctrine and practices, and of gurus in particular. Most notably, McKenna was one of the chief critics of Ram Dass’ story about nothing happening when Neem Karoli Baba took LSD; McKenna suggested that he had possibly palmed the dosage, or perhaps thrown it over his shoulder.

At times McKenna may have overstated his case, but hyperbole aside, his critique of Indian religion is valuable because it causes us to keep our eyes open and to question what is happening right in front of our eyes, without any veil of spiritual devotion.

For those of us who haven’t witnessed these things, it is reasonable and forgivable to ask whether “miracle stories” about yogis and saints are indeed just variations of a central “Big Lie”; Could a fog of ritual and spiritual devotion be put forth to dupe the masses? A lure to attract the spiritual seeker to some particular cult and then keep them in perpetual servitude?

In my own case with my guru Karunamayi, part of me that was always wondering why I never had the amazing mystical experiences that others seemed to be having around me. Why wasn’t I witnessing the miracles that I heard described hundreds of times? Was I personally blocked? Was I just not prepared for mystical experieinces yet? Was it my negative karma that was preventing me from being privy to such amazing grace? Was this dark karma manifesting itself in the form of “sour grapes”? Or was it Fear?

I will not offer the fruit of my ponderings on these questions just yet, but simply affirm the wisdom of carefully considering and weighing every possibility and experience we encounter in life.

Ram Dass and Terence McKenna in Dialogue, Mid- ‘90s

Soma – Still Kickin’ After All These Years?

In a synchronistic way, not long after I wrote the above, a fellow yoga teacher gifted me Stanislav Grof’s book, When the Impossible Happens. A book in which Grof speaks at length about…synchronicities! Grof also talks about his teacher, Swami Muktananda, describing some of the more remarkable “coincidences” that occurred between and around him.

It should be mentioned that syncronicity isn’t a characteristic unique to Muktananda. We find this phenomenon associated with many Indian gurus. I myself experienced synchronicity too many times to count.

One notable synchronicity Grof recounted was that immediately prior to meeting Muktananda for the first time he had been speaking with his wife, Christina. He was describing to her how in the course of his LSD experiences he had some profound encounters with Shiva, all without ever having any prior conscious connection to this particular Hindu deity. Then, upon the occasion of meeting Muktananda he received a darshan from him, a blessing usually transmitted through a gaze. After looking at him long and hard , the first thing this heir to the tradition of Kashmir Shaivism said to him was: “I see that you are a man who has seen Shiva.” Grof was impressed. So was I. but I remained cautious. Did the guru want to impress this highly respected psychologist? If so, why?

Grof goes on to relate some dialogue from that meeting which is particularly relevant to this discussion:

“I understand you have been working with LSD” said Muktananda. “We do something very similar here. But the difference is that in siddha yoga we teach people not only to get high, but to stay high. With LSD you can have great experiences, but then you come down. There are many serious spiritual seekers in India, brahmans and yogis, who use sacred plants in their spiritual practice….

He talked then about the need for a respectful ritual approach to cultivation, preparation, and smoking or ingesting indian hemp…and criticized the casual and irreverent use…by the young in the west. “The yogis grow and harvest the plant very consciously and with great devotion.”

….In the course of the discussion, I asked Muktananda about soma…mentioned more than a thousand times in the Rig Veda and that clearly played a critical role in vedic religion. This sacrament was prepared from a plant of the same name, the identity which was lost over the centuries…..

Talking about soma Muktananda dismissed the theory that this plant was Amanita muscaria, the fly agaric mushroom. He assured me that soma was not a mushroom but a ‘creeper’. This seemed to make sense and did not particularly surprise me because another important item in the psychdelic pharmacopeia, the famous mesoamerican ololiuqui was a preparation containing the seeds of morning glory (ipomoea violacea), which would qualify as a creeper plant…

But what came as a surprise to me is what followed. Muktananda not only knew what soma was, but he assured me that it was still being used in India to this very day. As a matter of fact, he claimed that he was in regular contact with vedic priests who were using it in their rituals. And according to baba some of these priests actually came every year down from the mountains to ganeshpuri, a little village south of bombay, to celebrate his birthday…Baba extended his invitation to Christina and me to visit his ashram at the time of his birthday and promised to make arrangements for us to participate in this ancient ritual.“

Stanislav Grof (right) with Fritjof Capra with Baba Muktananda

Intrigued, I contacted Dr. Grof to ask him whether he ever participated in the Soma ritual, and if so, what that was like? Dr. Grof told me that he never got a chance to participate in the ceremony.Then Muktananda passed in 1982 and Grof never pursued the subject further. However, more recently Grof told me of a Parsee woman friend who attended a ceremony in India where the priest said that the Haoma, which is the Zen Avesta name for Soma, is still being used in Iran by the Parsees….

While awaiting Dr. Grof’s response, I got back in touch with one of my first and most influential teachers on the yoga path, Swami Satyananda Saraswati (whom I call “Swamiji,” a term of affectionate respect, plus it’s shorter!). I sent him the above passage and asked if he knew anything about the modern day Soma ritual to which Muktananda referred. Swamiji’s response was quite interesting:

“Yes. We were traveling in Maharashtra a few years ago, when we were invited to attend a large Vedic yajna being performed for the initiation of a Vedic Pathshalla or Sanskrit University. They were making ahutis, offerings to the sacred fire, with a substance they called Soma. They claimed that it was the real Soma, handed down by tradition through the generations.

However, neither did the participants display any overt signs of enlightenment, nor did the members of our group who all participated in drinking the soma, reflect any changes in their attitudes or behaviors. I, too, drank the Soma juice, and did not feel any different because of having partaken.”

Swami Satyananda Saraswati’s account leads me to doubt that the priests in question were using the original Soma. Perhaps they were using an inert nominal stand-in?

As we have seen, any number of other psychoactive substitutes have claimed to be the elusive Soma, but if the originalVedic Soma were still in existence, surely it would have come to the attention of the scholarly community by now?

Swamiji interestingly concluded his response to me with the words:

“Therefore, I remain much more interested in the inner Soma – which we define as the nectar of Pure Devotion.”

I can certainly attest to the power of the “nectar” of which Swamiji speaks, as I experienced it on numerous occasions while on tour with him and Shree Maa, a great woman saint from Bengal, in the late nineties.