(This essay follows from a conversation and question from Rick Archer at Buddha at the Gas Pump.)

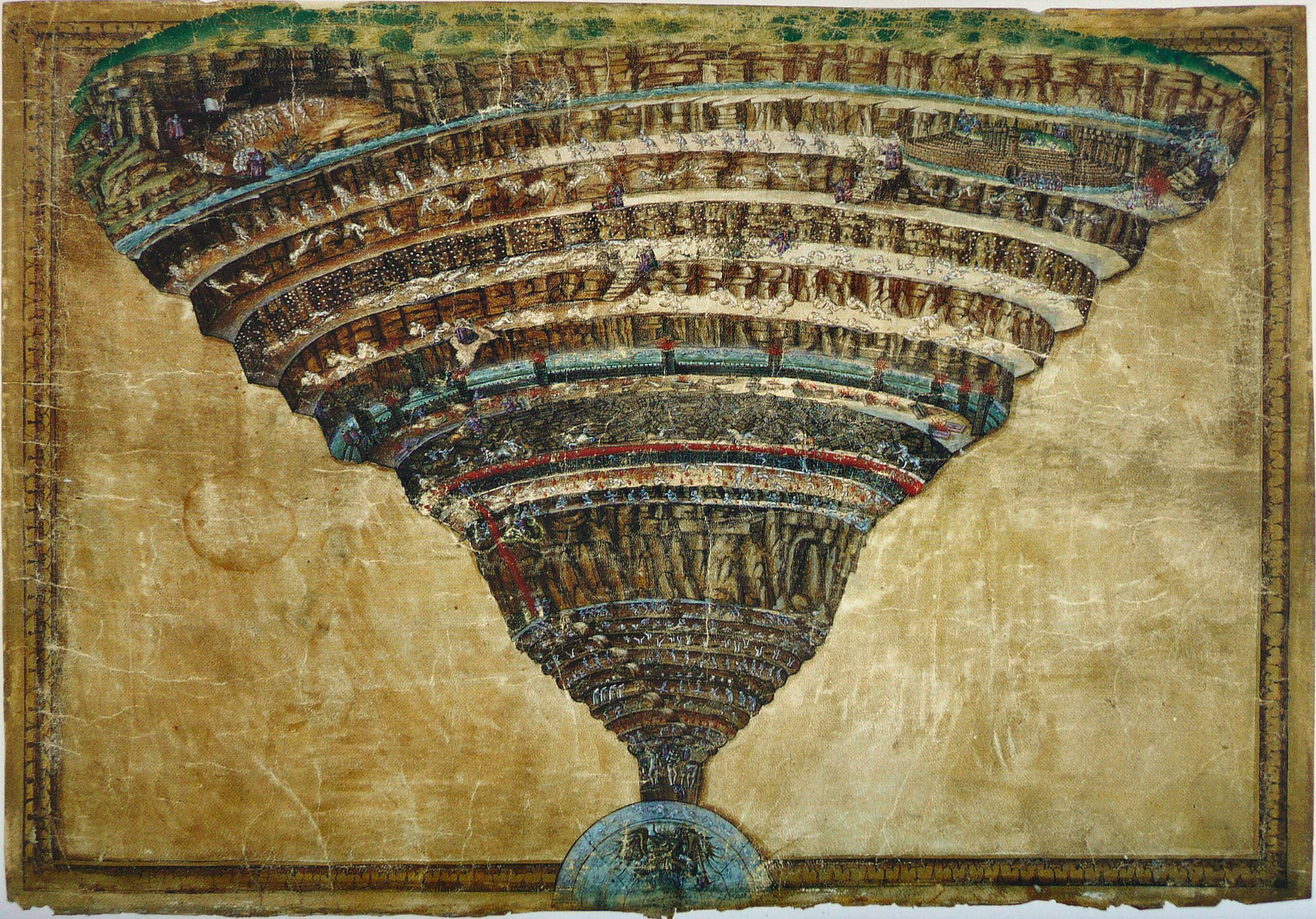

The question (“Can we know anything with certainty?”) is very complex to answer fully, so I am going to try to parse out as many of its different nuances as I can get to in an essay. This is one of the core questions because it arises for everyone at some point leading to extreme skepticism, if not cynicism. And with good reason, since the world is filled with deception of seven main sorts: misinformation, disinformation, corrupted information, obsolete information, partial information, incoherent information, and encoded information very difficult to decipher.

In addition, we have to reckon with different kinds of knowledge: what the French philosophers (who are, or at least were until recently, way ahead of the North Americans) call connaissance, savoir, and savoir-faire. I would translate them as empirical knowledge, direct knowledge, and know-how (knowledge that may not be translatable into concepts, and may be somatic, intuitive, or a skill set that has been mastered and then sedimented into the pre-conscious level of the mind.)

That knowledge which deals with the phenomenal world (connaissance) is by its nature empirical and pragmatic. It can be grasped inductively, and speculated upon abductively, but always with a measure of doubt. (I may have only ever seen white swans, but a black swan may always appear, to use a fashionable example.) This kind of knowledge comprises all of what is currently called science, and most of the rest of what we think we know, which means we can never know it absolutely. Another reason we cannot know anything in the objective world absolutely is that the world itself is relative, in flux, impermanent, etc., as Buddhism famously emphasizes, as are we as observers of that world.

That leaves us with the question of savoir. This is direct knowledge. An everyday example is: “I know I have a toothache.” This knowledge—in terms of the presence of pain—is unquestionable (for oneself—someone else can surely doubt the matter). It may be discovered later that it was a psychosomatic or hysterical pain that was in fact unrelated to any actual tooth. But nonetheless, the “toothache” was real. So here we have to make a distinction between the signifier and the signified. I may use a word that does not correspond to the actual state of affairs (since the pain was not arising from the tooth, but rather being projected into the tooth) but it nonetheless describes accurately the phenomenology of the sensation at the first level of attention.

French psychoanalysts employ the word savoir to mean: “I know the desire of my heart—meaning my unconscious self.” Someone in analysis can come to know their deep ego-self—which would imply that they would not say it was a toothache, when it was unconsciously an ache to bite the internal mother’s breast, for example. One can come to know accurately one’s dissociated fragments and their phantasies, can integrate them, can make the entire unconscious conscious, at least in theory. Or can one? Could the apparent savoir in fact simply be indoctrination into some form of psychobabble? From a third-party perspective, that certainly cannot be ruled out. But if someone says: “I know that I am feeling what I am really feeling,” there is also no basis to negate that. But notice that now we are speaking of feeling, rather than facts or concepts.

So here we must digress a moment and deal with another complexity in the field of knowledge. Jung thought we have four psychic functions: thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuition. It is more often asserted nowadays that humans have seven or more kinds of intelligence (Howard Gardner, who made this claim famous, delineated ten types). These are: verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, interpersonal, intrapersonal—and then he added three more that are a bit more fuzzy, that he called naturalistic, existential, and moral.

These last three should probably be considered applications of intelligence, rather than irreducible and inherent forms. For example, a psychopath would not have moral intelligence, by definition; an autistic person would probably not display much naturalistic or existential intelligence. But these deficiencies are artifacts of decisions made at the moment of the developmental formation of the proto-ego. This leads to the question of the locus of intelligence. Does it emanate from the Atman (pure Spirit) into the soul (buddhi) and then get projected into the ego (which may repress or foreclose certain aspects of it)? And what is the essential nature of intelligence? Perhaps a starting point for a definition is to call it the capacity for discerning patterns, making connections, and flowing with the energetic processes of the phenomenal flux. But also it is the capacity for creativity, for inventing patterns, for imagining new forms, new meanings, and new approaches to navigate the plane of appearance and download information from the Real. Without intelligence, there can be no knowledge. But is creative intelligence ultimately the source of knowledge itself? Is it the essence of the Real?

Clearly, the kinds of knowledge located in the realms of the kinesthetic, musical, and spatial dimensions are less debatable than Gardner’s final three (if we leave out such issues as optical illusions, musical taste differences, phantom limb pain, etc.) because they do not answer to a correspondence theory of truth. Moreover, mathematical knowledge is by definition not empirical but deductive, and does not directly pertain to the phenomenal world, but rather is a function of arbitrary rules of thought (of course we can get very metaphysical about the ontological status of number and numbers, and the mystical significance of zero, issues which have in fact created a crisis in the field of the philosophy of mathematics, but all computers will add integers the same way.)

This brings us to the need for another type of categorization of knowledge, into seven realms. We can speak of common knowledge (comprising such matters as knowing what side of the street to drive on, how to count your money, how to read a map, how to use a computer, etc.). Of course this is relative knowledge, superficial, culture-bound, time-bound, etc., and of little interest to our discussion.

Then there is specialized knowledge, which comprises all the bodies of knowledge necessary to functioning in a specific profession or field of labor or scholastic discipline. If you have to undergo surgery, you definitely want to know that your surgeon knows what he is doing (you may also want to feel sure that he likes you, that he is not in some family or financial crisis, or having alcoholic binges, or coming to work high on drugs). Can you know any of this absolutely? Unfortunately: no.

Then, there are two realms of knowledge focused on in the field of psychoanalysis.

One is forbidden knowledge. This is comprised of memories, decisions, facts, and understandings that have been repressed into the unconscious because the dysfunctional family system, and later society at large, mandated such amnesia. The skeletons must remain locked in the closet. This creates much of the so-called cryptomnesia problem. How do I, or does a therapist, know if what seem to be repressed memories are historically accurate, or contaminated with phantasy material? This quandary led Freud to change his theory from naïve belief in what he was told by his patients (the seduction theory) to a more sophisticated belief in the Oedipus complex, which he employed to debunk recollections of childhood sexual abuse, and reinterpret according to his drive theory. Is either of his theories correct? Can one even appropriately impose any general theory on such narratives? This has been grist for hundreds of books on the subject. The same predicament faces us when we consider social knowledge. Was 9/11 an inside job? Is Paul McCartney really dead and being impersonated for decades by an imposter? Is there a Nazi military base in Antarctica? Some of these questions could be answered, if we were allowed to do the proper research. But we may not be psychologically allowed to want to do that. This brings up the intersection of knowledge and free will.

Of course, this issue becomes even more extreme when clients undergo past life regressions, which I used to do regularly in my professional practice many years ago. But if a regression brought about a spectacular release of a physical symptom (a remission of cancer, for example) then who is to question at least its pragmatic efficacy? But does that solve the epistemological quandary? Certainly not. Even more extreme, and perhaps urgent, is the question of truth in cases of alleged alien abductions. I began to study this subject in depth many years ago, when I became an on-call therapist with a spiritual emergency network (connected with Stan Grof and others). It was important to know if someone was psychotic (which was the absolute preconception of mainstream therapists and psychoanalysts) or hoaxing, or hallucinating for other reasons than psychosis—or if they were really abducted by actually existing beings from another planet who had secretly come to this planet, built bases underwater and underground, and had possibly malicious intentions toward our species. Or, if they were space brothers here to help us save our world from the illuminati, or some such conspiracy theory. The subtlety of discernment required to filter out indicia of authenticity from duplicity in such cases is difficult, but perhaps not impossible. I could go on multiplying scenarios, but you get the picture.

Then, there is the realm of unbearable knowledge, which comprises such horror and dread that the information cannot be faced without the person going into possibly terminal meltdown and malignant depersonalization. Sometimes, forbidden knowledge can also be unbearable. But usually one can have general forbidden knowledge that can be retrieved (for example, that one was sexually abused) but not get the full repressed affect and clarity of memory of the pain, shame, murderous rage, and terror of death that accompanied the actual event(s).

Beyond that we encounter the realm of metaphysical knowledge. I will skip that realm for the moment. But to the extent that it is made up of beliefs, or even interpretations of non-ordinary experiences, like satori, angelic visions, near-death experiences, etc., one can never be certain of the significance of the content of the experience in an absolute sense. If we take the example of Anita Moorjani, her NDE definitely resulted in remission of all her cancer symptoms and a transformation of her life. But does that mean that she has a true conception of the after-life? She received a lot of psychological insight, but we cannot say much about the metaphysical understanding she came back with. It was congruent with prior anecdotal narratives of the same sort. And it has a lot of practical moral value for us. But we do not know what would have happened to her consciousness if she had not been revived from her coma. And her story tells us nothing about ultimate reality.

Then there is shamanic knowledge, which is comprised of a broad set of skills acquired by adept shamans and voodoo masters, including the savoir faire for exorcising demons, removing curses, combatting covens of black magic practitioners, channeling souls of the departed, precognition, remote viewing, subtle body healing, etc. The shaman has no doubt about his knowledge. But its efficacy may indeed depend on the faith of his clientele. A degraded form of shamanic knowledge may even include the understanding of the placebo effect. But the core of that effect, as well as the effectiveness of all shamanic actions, must remain within the Great Mystery.

From a more philosophical level, we can also recognize that all linguistic propositions asserting some kind of knowledge occur within and pertain to a particular frame of reference. From a different frame of reference, the same event that is the predicate of the knowledge will have an entirely different significance, or may not even be an event at all. So what is important is not really knowledge so much as the capacity for paradigm shifting. Since conceptual knowledge is relational, and all beings inhabit a different frame of reference, the more open the intellect (the buddhi) is to reinterpreting its knowledge in other frameworks, and to deciphering the signifiers of the other in terms of their own paradigm, the more there can be communication and communion that can lead to the knowledge that is really essential, which is the Knowledge of the Self in the Other.

What all this impossibility of knowing reduces down to is the unreality of both the known and the knower, the relativity of every frame of reference, the one perhaps undisputed fact that everything is a matter of dispute, all is paradoxical, every thesis entails its antithesis, and there is no final synthesis. The implication is that we inhabit an infinite field or ocean of consciousness, and we ourselves are merely temporarily formed bubbles riding on waves traversing that ocean. The waves are recognizable now as quantum waves, wave functions that are in endless superposition, but that can be apparently collapsed into seeming material realities by observation and desire. So we know what we want to know, but all we know is the projection of our lack into objects of desire, and all are located only in our minds. Those minds that seem to be localized in bodies in a world are only locally coherent, but utterly incoherent in relation to global reality, which is unknowable because it is made of uncollapsed quantum potentiality that is seemingly collapsed into infinite fractals of individual consciousness ignorant of its true nature. But is any of this certainly true, or just another mirage of consciousness anticipating its own terminus with a vision that is really nothing but a hope that suffering and mortality can be overcome?

Finally, we come to Supreme Knowledge. This refers to direct realization of the Absolute. By definition, this cannot be defined. It is a different kind of knowledge, not reducible to symbolic form. It cannot be grasped by a subject who wants to know an object. In fact, there can be neither subject nor object, which prove to be the obstacles to Supreme Knowledge, which is realization of absolute non-duality. Because of the conditions inherent in knowledge of the Unconditioned, no one can be master of that knowledge. In fact, the ego that desires to know must die completely if the Supreme Knowledge is to be retained in the form of Being, not knowing.

In short, all we can know is that we cannot know, but that there is realization beyond the level of intelligence of the human subject that emerges when the subjectivity dies into the Real. But what remains is only an uncanny smile. And total inner silence.

All the rest that emerges from the voice box is commentary, coming from a source that is no longer an individual self, at least not a subjective self. But there is a flow of loving response aimed at bringing the other ever closer to the Real that cannot be described or conceived, but can be known through the death of the knower, which ends all belief in the reality of the phenomenal world, space, time, multiplicity, and difference. Nothing can be known because there is nothing real to know, including a knower. But the realization of the Absolute (beyond even the concept of Being, since it is equally Non-Being) fulfills all desires, ends all fears, and brings utter peace.

The result can be seen in the lives of great sages. But it cannot be known for certain until one has gone through the eye of the needle, when all doubt and the doubter shall cease.

Namaste,

Shunyamurti