This article is adapted by the author form his book Returning to Sacred World: A Spiritual Toolkit for the Emerging Reality, due out in 2010 from O Books.

Like many of us in the western world, I grew up in a family that went to church on Sunday mornings. In my particular family it was the Anglican Church in central Canada. Prayer was a core principle of the teachings that came down to me as a child and a significant part of the Sunday services. I recall sliding off those wooden benches onto my knees several times during every service. And at home there were a few years when my mother made sure I said my prayers before bedtime every night.

There may well be people around who grew up in a similar environment and made a deep and true connection with the power of prayer. I certainly did not get it and in general I think something crucial was missing. It’s no shocking insight to point out that despite its Christian face, the culture we were embedded in in mid-twentieth century, white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant North America, was deeply under the spell of the scientific-materialist worldview. In stark contrast to a great many traditional, indigenous cultures — and notwithstanding the great anthropomorphized eminence in the sky who was reputed to be watching our every move — we were not taught to believe in the reality of spirits in the world around us, much less that we could actually communicate with them and ask them for assistance. I doubt many of us believed with conviction that anything real at all could come from praying. As the Native Americans say: in the white, European religions people go to church to talk about God, whereas in their traditions people go to church to talk to God, to talk with God.

So I said my prayers at night but I had no assurance or confidence that anyone was listening. And, like many of my peers, as I moved through adolescence I came to think of religion as irrelevant to my life. But I’ve always had a spiritual yearning and when I heard about the religions of the Orient while in university I was immediately interested. That interest eventually led to a long engagement with Tibetan Buddhism, particularly as taught by the brilliant “crazy wisdom” guru, Chögyam Trungpa.

The word “prayer” wasn’t in general use in that Buddhist environment, but there were a lot of chants. The chants were verses, paragraphs, shorter and longer passages — most of which had been translated into English — which were employed to accompany a variety of events and practice sessions. We read them aloud together, recited them from memory, and included them in our private practices. These chants were reminders of the power of the truth (Dharma,) invocations of wisdom energies, pleas for the banishment of negative forces, and stories of the achievements and dedication of great masters. The chants were also expressions of devotion and gratitude to these masters and to the wisdom of the teachings, as well as appeals for the awakening and blessing of all sentient beings.

Again, though we recited the chants with sincerity and passion, I don’t believe many of us had confidence that we were doing more than strengthening our own commitment, compassion, and devotion. The great majority of us were, after all, still under that rational/reductionist spell. With the possible exception of a few unusually sensitive practitioners, we still had no means and support for gaining access to a living spirit world. Our Buddhist teachings even led us to be suspicious of granting credence to external phenomena of that nature. And many of us were recovering theists who tended to take literally the presentation of Buddhism as a non-theistic religion.

During the years of my most active involvement with Buddhism, I’d stayed away from psychedelics, even from cannabis. Although many would have admitted that their earlier use of substances like LSD sparked their interest in spirituality, the prevailing view in the community was that psychedelics offered only a false, artificial enlightenment and were of no value, or worse, on the path of awakening.

But I never did lose my curiosity about the enlightening potential of psychedelics, and a cover article/interview with Terence McKenna in the L.A. Weekly in 1988 or 1989 triggered a revival of that interest. This was exciting new information. I was living in Los Angeles at the time and I drove up to Ojai to hear McKenna talk that weekend.

After a few dubious attempts to breach the far shores alone following McKenna’s “take a heroic dose of mushrooms, then sit down and shut up” approach, I began to think I might negotiate these deep waters more successfully with skilled guidance in a ritual context. As intention often seems to go, one connection led to another until about seven years ago I was given the phone number of a highly respected elder of the Native American Church. This man, Kanucas, invited me to join them for one of their all-night meetings.

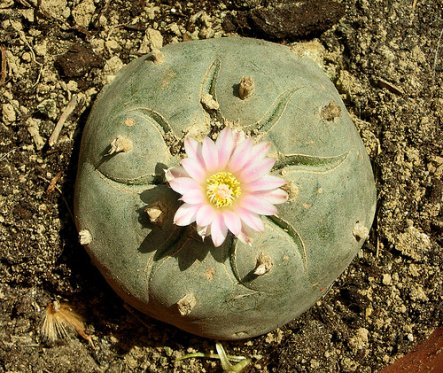

My inspiration for going to that first meeting was the idea of combining these two passionate interests in my life: entheogens and spiritual practice. I thought I was going to get help from the peyote plant. I hoped it would deepen my meditation practice and help me work through whatever obstacles to awakening remained in my consciousness.

What I didn’t know then but began to see even in that very first ceremony I attended was that these were prayer meetings and that I’d stumbled upon a stunningly different approach to prayer than anything I’d previously encountered. I’ve gone to a lot of meetings since then and I’m still learning what’s really going on and what’s possible.

Maybe it would be helpful to give you a brief description of the environment and form of the meetings. Most meetings are held at someone’s request. That person is then called the sponsor of the meeting and determines its purpose. The possible reasons for a meeting are many. It could be anything from a birthday to a baptism, an expression of gratitude for somebody, or a request for healing.

The meetings are usually held in a tipi. They typically start around 9 or 10 in the evening and continue to anywhere from about 9 until noon the next day. A crescent moon altar made of sand is built and a fire started before the participants enter the tipi. After a few introductory words from the person running the meeting, known as the roadman, the sponsor is called upon to explain the reason for the meeting. That reason then becomes the “main prayer” for the night and the participants are expected to direct their prayerful intention toward that purpose for much of the night. In the hours before dawn we’re also invited to pray for those close to us in need of help and for ourselves.

As it is in numerous indigenous cultures, tobacco is considered a powerful sacred medicine and is used to pray with in various ways during the ceremony. At the beginning of the meeting a pouch of tobacco and a packet of corn husks cut a little larger than rolling papers are passed around the circle. Everyone rolls one of these and begins to pray on behalf of the sponsor. Shortly after that the peyote medicine is also passed around the circle.

Not surprisingly, music is a central element of the ceremonies. There’s a large body of Native American Church prayer songs. If you’ve heard the peyote song recordings of Primeaux and Mike you’ll have a rough idea of what they’re like. The songs are considered to be the wings that carry the prayers and are sung through much of the night. A set of instruments consisting of the roadman’s staff, a gourd shaker, a sage stick, and a water drum move around the circle. Everyone who knows some songs sings a set of four with or without the accompaniment of others. When the medicine takes effect and the energy really gets rolling, especially when there are a lot of experienced singers, I’ve often found the songs to be impossibly rich and moving. As one elder described it to me, when it’s really clicking the songs begin to sing the singers.

The water drum is a key player in the power of the prayer songs. As part of the planning for a meeting the roadman generally asks someone to “carry the drum” for the night. I’ve been told by elders that the drum is a living spirit. One drummer told me that he sometimes sees the energy moving out from the drum, carrying the intention of the singer.

The fire is also referred to and treated as a living spirit. The fire person for the night tends it with great care. The long, split logs are always kept in the same arrow shaped configuration and as the night progresses the coals are gradually formed into particular shapes, often a large bird like a phoenix or eagle. The roadman and other experienced members have occasionally reminded us to pay close attention to the fire. They say it has things to show us.

I said earlier that this environment introduced me to a radically different way to pray. As well as the potent mixing of music, medicine, and prayer, the other key ingredient of those meetings which struck me so forcefully was the way people pray. There are no books, no liturgy, no memorized prayers. From the start I was deeply moved and impressed by the eloquent, straight-from-the-heart talk I’ve heard again and again. People just express themselves. For example, around about dawn, the wife or close female associate of the roadman goes out to get a bucket of water and a ladle, then returns, places the bucket close to the fire, and kneels in front of it. She is given a tobacco to roll and begins to speak. These monologues or prayers often go on for close to an hour and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been moved to tears by the waterwoman’s words.

One elder, Susan, who carries the female lineage for her people, told me that when she’s doing that morning water prayer she often has no idea what she’s saying. The words are just coming through her, sometimes even in the old languages that she somehow has to intuitively translate on the spot. One morning after a meeting she said that during one of those prayers she felt the distinct presence of perhaps hundreds of her female ancestors leaning over her and supporting her. When Susan told me that, another woman sitting nearby said she’d been at that meeting and seen those women lined up behind Susan.

One of the essential teachings of the Native American Church is that a prayer is greatly potentiated when all those present can settle their minds and bodies fully, get out of their heads, and enter into a concentrated shared focus — one mind. Kanucas has been sitting up in these meetings for over forty years now. One night he told us that when he was young it was all experienced participants who could stay still in mind and body for the whole night, often not even getting up to take a pee. He said that, with the assistance of Grandfather Peyote, that undistracted focus and intention could accomplish just about anything. As the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick wrote, “Matter is plastic in the face of mind.”

I’ve seen a lot of instances of the effects of prayer now, and over the years have heard many first hand stories of remarkable healings. I’d like to share two of those stories with you.

One night a young Native man, known to some of us as Wild Willy, told me he’d had a bullet lodged near the base of his skull for a couple of years. Surgeons were unwilling to attempt removal because of the bullet’s delicate placement and the fear it would cause serious damage if moved. The bullet wasn’t deep enough to be life-threatening in the near term, just embedded enough to cause bad headaches and other unwanted symptoms. A special healing ceremony was held for Willy, accompanied only by a few of the most experienced elders. All ate generous quantities of the peyote medicine, smoked prayer tobacco, prayed and sang hard, and performed other healing rituals. Willy was wearing a small medicine-bundle pouch hanging from a cord around his neck.

The ceremony lasted all night and in the morning he noticed the pouch felt a bit different. He then reached in and was astonished to find the bullet. If it helps the skeptics at all, I want to make it clear that this was in no way a commercial or public transaction. The elders who confirmed the story had nothing to gain from any fabrication or exaggeration. In fact, the general rule of thumb in that environment is that it’s unacceptable to charge money for this kind of healing work.

The other story comes from another Native man named Norman, who has told this story several times in ceremonies I’ve attended. His daughter, about twelve years old at the time of the event, was in a serious car accident and was taken immediately to hospital. When Norman arrived she was on life support. The doctors told him that her spinal cord had been damaged and that she would be permanently and severely brain-damaged and paralysed, if she recovered at all. They asked his permission to remove her from life support. Norman hastily arranged a prayer ceremony for that night and invited only a handful of experienced elders and friends.

The group prayed all night for the healing of the girl and in the morning sent Norman off with a number of prayed-over objects and a small amount of the medicine. Arriving at the hospital, Norman asked to be left alone with his daughter. He placed the objects around her, put some of the medicine on her lips, and prayed hard. After some time the machinery she was hooked up to began to act up and a staff member came running into the room saying, “What have you done?” As Norman told us, within an hour his daughter was off life support and breathing on her own. She was eventually able to resume her education and has now completed high school.

I’ve learned from my experience in the Native American Church and from the comments of experienced elders like Kanucas that there are several key factors in the “success” of a particular prayer. First, it takes great confidence and conviction. Second, you need to be specific about what you’re asking for when you call on the Spirit to help out. As the saying goes, be careful what you ask for, you might get it. Third, there are often complex forces at play. The mysterious ways in which the Spirit moves may bring changes that aren’t obvious or don’t appear on an expected timeline. It may take years for the prayer to take effect and Spirit may have other ideas for what the recipient of the prayer needs at any particular point.

A brief anecdote about my cousin Ross may help illustrate this. Ross called me out of the blue after we hadn’t seen each other for nearly thirty years. During the course of a brief stopover in my city, he told me he had hepatitis C. I arranged to sponsor a healing meeting for him. What Ross didn’t tell me (or those at the meeting) was that he had also been deeply in the grip of alcoholism for many years.

That meeting took place three years prior to this writing and until recently I had assumed that Spirit’s intention with Ross was to get him away from the booze, since he never again took a drink after that night. Meanwhile, the hepatitis, while showing signs of improvement, did not seem to be going into complete remission. But just recently, after I’d had no contact with him for another year and a half, Ross again appeared in my life, announcing that new tests showed absolutely no evidence of the hepatitis and that he’d never felt better in his life.

The fourth key factor to consider regarding the effectiveness of our prayers is that we can’t interfere with anyone’s karma, agenda, or desires. We can only ask the Spirit to help the recipients of our prayers with what they want and need for themselves. They have to ask the Spirit for help with the same degree of confidence and conviction felt by those who are praying for them.

I want to return briefly to this meeting of prayer and medicine. A wealth of anecdotal evidence suggests that prayer can have remarkable, even miraculous effects. Clearly, it doesn’t require the admixture of plant medicines for prayer to work. With enough shared intention and confidence it may even be that we can help heal the planet and put it on a sane and sustainable path. The medicines, or entheogens, are sometimes called non-specific amplifiers. Healers in traditions that work with these plants often say that they greatly strengthen the effects of their prayers and healing efforts on behalf of the patient.

I participated in some ayahuasca ceremonies outside of Iquitos, Peru last summer with an ayahuasquero named Percy Garcia. Before the ceremony got under way one night, Percy told us that he has a relationship with eight spirit doctors whom he calls upon to guide him through the ceremony. Someone asked him if he could contact them without drinking ayahuasca and he replied that, yes, he could, but that with the medicine in him the connection was much stronger and clearer. Kanucas has told us a few times that when he eats the peyote medicine he calls upon the Spirit and the Spirit talks to him. He’s said more than once that he means that literally. The Spirit tells him how to work with particular situations and individuals throughout the night.

So it seems that we in the modern societies have a great deal to learn at this time. The message coming from indigenous spiritual traditions, from the Earth peoples, from the plant medicine peoples, is that we’ve cut ourselves off from a potentially life saving knowledge: that the world is alive in ways far beyond our current conditioned understanding, that we need to reestablish that connection with the Spirits, with the living Gaian mind in its many forms. If we can find skillful ways to combine the visionary, teaching, healing medicines with our intentions, with our prayers, a whole new landscape of possibility opens up.

I’d like to leave you with one of my favorite little passages, from a Native American elder and healer named Wallace Black Elk: “So I pray for you that you obtain the same power I have. You and I are no different. It’s just that understanding. You just drifted away from it, just walked away from it for thousands and thousands of years. That’s how come you have lost contact. So now you’re trying to find your roots. They are still here.”1

1. Wallace Black Elk and William S. Lyon, The Sacred Ways of a Lakota. New York: Harper Collins, 1990, 14.

Stephen Gray was a student, meditation instructor, and teacher of Tibetan Buddhism for many years and has been a member of the Native American Church for the past seven years. Stephen has published several articles on themes related to his forthcoming book Returning to Sacred World: A Spiritual Toolkit for the Emerging Reality. Visit his website here.

Image by Andyshineyes, courtesy of Creative Commons license.