The following expose details the outstanding art from psychedelic artist Alex Grey.

Introduction

On the morning I started writing this, a five-year-old named Caleb happened to be visiting the house and interrupted my writing session to tell me (and this is an exact quote):

“Jonathan, I see ghosty things other people don’t see.”

I was tempted to reply: “That’s interesting because I just started writing about a grown-up named Alex Grey who also sees ghosty things other people don’t see.” Instead, I asked Caleb to describe one of the ghosty things, and he said he saw a cupcake with a “skeleton head” in it. There were more details I couldn’t quite follow due to the limits of his five-year-old vocabulary and his unfortunate inability to paint like Alex Grey. This synchronistic incident was a timely, and somewhat eerie, reminder of why we need Alex Grey — he sees ghosty things other people don’t see and he does paint like Alex Grey.

In fact, Alex Grey can paint unseen, ghosty things to a degree of potency that can only be compared to a Thor-hammer blow to the head while your body is being strafed by DMT-coated diamond bullets. Scientific testing indicates that some of Alex’s paintings generate phased bursts of nuclear magnetic resonance. This type of scalar wave NMR has been linked to high-lumen retro-chronal causation effects (sometimes called “balefire“), which are capable of matrix deletion of toxic patriarchal structures extending into the past. For example, ever since Alex began painting Net of Being, I can no longer find any record online, or anywhere, of Rasputin’s two decade reign over Oceania. At their best, Alex’s paintings seem like unauthorized glimpses through the interstices of the matrix, the fever dreams of third-stage, space-folding Guild Navigators living in giant tanks of pure spice gas causing illegal ruptures in the space-time continuum. (Note to literalists: The above are what are called “jokes,” so stop asking me to clarify or document.)

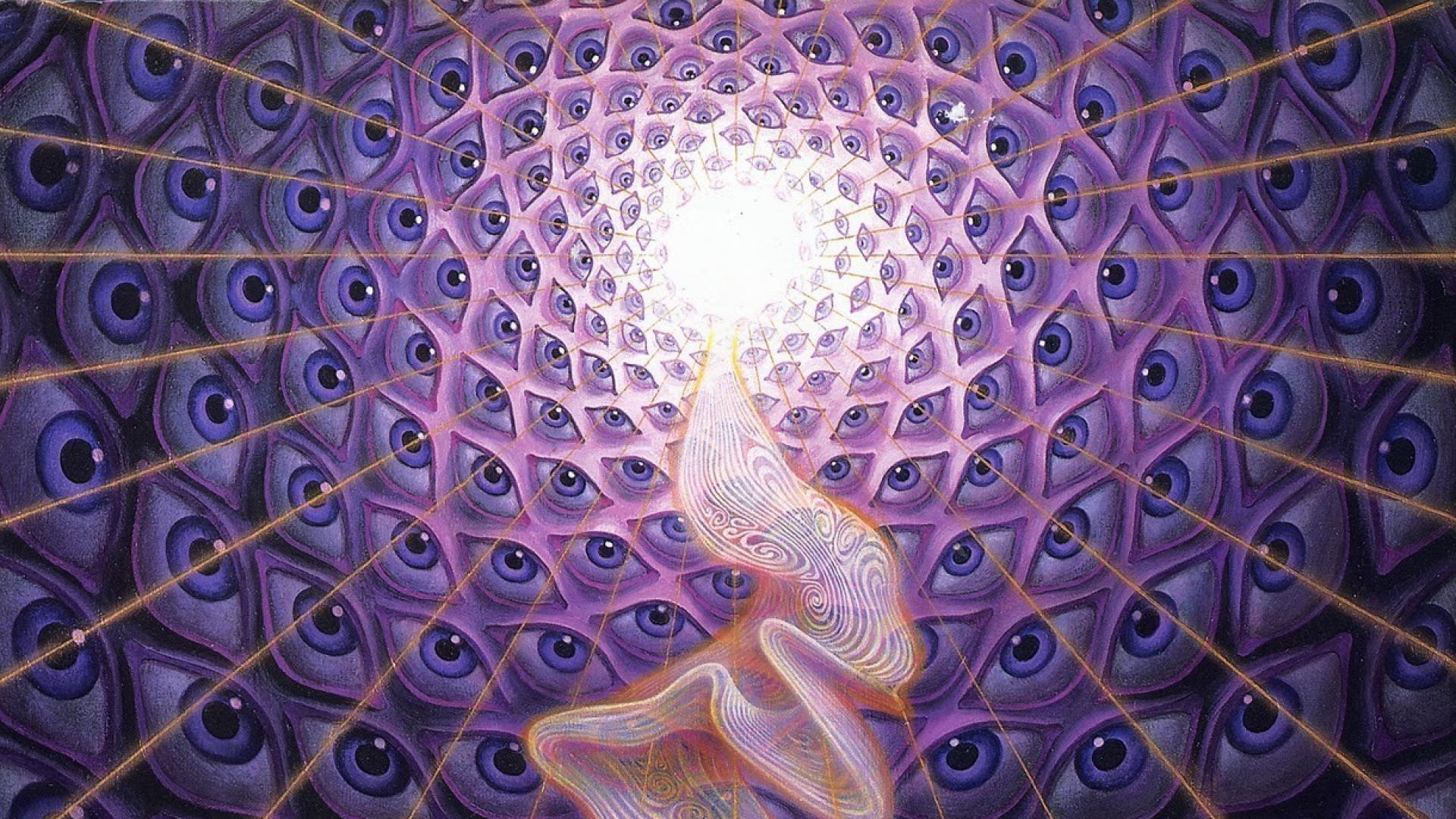

For less than seventy dollars you can own all three of Alex’s monographs — Sacred Mirrors, Transfigurations and the just published Net of Being. Holding these three books in my hands, I feel like I have paid the least price possible to obtain the Philosopher’s Stone, or at least the glossy paper version of an alchemical portal of some kind. I feel like I am holding a spiraling, eye-encrusted atlas of the hidden realms. No home would ever be complete without this trilogy on the shelf available for spiritual cartography, easy reference to the unseen and bottomless rabbit holes on demand.

Although I know Alex, or at least have had several conversations with him, and the reader can probably detect that I am partial to his work, I won’t always be easy on him in this essay. In some sections, like “Don’t Pray the Grey Away” (which critiques Alex’s transforming relationship to darkness and shadow material) I’m going to offer him some challenging criticism. These critiques are not merely to counterbalance the praise myself and so many others want to lavish on his work. I’m hoping this will be useful criticism since I regard Alex as much more than a private citizen and painter. I consider Alex to be a potent, alchemical mutagen introduced into the collective psyche that we all have a stake in keeping as potently mutagenic as possible.

When Terence McKenna was asked what we should do given the dire state of the world, he replied: “Push the art pedal to the metal.” Alex has pushed the art pedal past the heavy metal darkness of H.R. Giger, past the existential despair of post-modernism and trendy nihilism, past the heat ripple distortions of the collective asphalt and into the forbidden realms under-glowing the meat puppet antics of the Babylon Matrix. Stephen Daedalus, James Joyce’s literary alter ego, summed up an aeon when he said, “History is the nightmare from which I am trying to awaken.” Alex follows trails of red pills down rabbit holes, waking up repeatedly from the nightmare of history to see through the world that’s been pulled over our eyes. Quite a number of people have had parallel voyages of discovery, but the difference is that Alex brought back to us high-resolution images from across the threshold. For this reason, I see Alex as belonging to humanity, in much the same way as I see the Mars Curiosity Rover with its seventeen cameras, the best optics we’ve ever had roving across the surface of another world, to be public property.

The presumption I make in writing this essay, a presumption that some may find arrogant, is that in return for the two Alex Grey calendars I have purchased, plus up to a dozen of the postcards, perhaps as many as a half dozen of the much more expensive lenticular postcards, and a couple of his books, I am entitled to view myself as a majority shareholder in the Alex Grey enterprise with the right to offer all kinds of evaluations and suggestions about how the enterprise should go forward. Part of this presumption comes with the character flaws of being a demanding and egocentric mutant, but part of it is because Alex belongs to humanity, our high-definition, eye-encrusted Curiosity Rover exploring forbidden, unseen realms. We all have a vested interest in seeing that his high-stakes artistic mission succeeds.

Much of Alex’s work is intended to be an illustration of classic phases of spiritual transformation. But, as Alex and his work recognize, there are spaces where spiritual transformation and evolutionary metamorphosis overlap and coalesce like the multi-Janus-faced entities of Net of Being. Much has already been written, including by Alex, of the classic spiritual face of his work. In part two of this essay I will focus my gaze on the evolutionary metamorphic face of his work, and point out the myriad ways it manifests what I call the Singularity Archetype.

In addition to the enormous value of his work, Alex also has great value to us as what I call a “talismanic personality.” In a review of the movie Lincoln, I describe a talismanic personality as follows:

A talismanic personality is one that is numinous and inspiring, an exemplar of wholeness that reminds us of what Lincoln called the ‘better angels’ of human nature. In the presence of a talismanic personality, all that is superficially glamorous is revealed as the shoddy, mediocre product of false personality and inflated ego.

Alex personifies a person who is in touch with and coming from what Aleister Crowley called “True Will.” He is someone who recognized his mission in life very early on and has been faithfully pursuing it. By the time he was five years old, Alex had already completed a number of drawings of skulls and skeletons and other visual motifs reflecting his creative preoccupation with death.

Life Cycle

Alex’s self-portrait entitled Life Cycle, drawn at age 17, is a brilliant revelation of his essence and life mission. His eyes are obsessively focused, and he is an image of alchemical tension, with one hand touching the boundary between a fetus and a corpse and the other hand raised in prayer. He seems to be surrounded by ancestral spirits.

Alex recognizes and fulfills the foundational core of most True Will: commitment to consciousness and service to others. Also, unlike many of the folks that Alex finds to be talismanic personalities (highly talented people with enormous, unintegrated shadows — more about this later), Alex seems to be consistently benign, gentle and generous with the people who encounter him. He is not the sort of genius, like Picasso, who is best appreciated from a safe distance.

An Invisible Giant in the Realm of Art Worldlings

As far as I can tell, Alex Grey is invisible in the world of “serious art.” First, according to the postmodern world, spirituality is an incorrect subject for art, literature, film or any sort of culture. The only correct subject for “serious literature,” as Robert McKee has pointed out, are downbeat stories about failed relationships. Spirituality is considered the domain of evangelicals and the hoi polloi, and is far too unsophisticated a subject for art of any kind. Also, the use of skill in artwork, and accurately rendered representational images, indicates an amateurish rube whose art could never be taken seriously.

Net of Being excerpts what is probably the only time the New York Times condescended to notice Alex Grey’s existence. Reporting on the closing of The Chapel of Sacred Mirrors, the Times informs us that the chapel was “…a curious, over-the-top combination of art gallery, New Age temple and Coney Island sideshow.”

The tone of the article suggests that it is generously restraining the devastating sarcasm it might otherwise unleash if it weren’t showing good natured, bemused tolerance for any readers who might have fond memories of this quaint and colorful little New Age theme park that was closing anyway. The chapel, the Times continues, was a “theatrical environment…designed to transport paying visitors into states of ecstatic reverence for life, love and universal interconnectedness.” The sophisticated reader is meant to admire the tasteful restraint with which the Times implies that here was a place where suckers actually paid money to see a bunch of New Age clichés. I wonder how many Times reviews of exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art specified “paying visitors”?

(Note to reader: This is the first of several “related topics.” It delves into what I think is wrong with the art world. If you came here only to read about Alex you could skip ahead to the next subheading: “Exposing ‘Casual Sex’ as an Oxymoronic Delusion and other Third Rails”)

One of the best assessments of what’s wrong with the art world is an article by Tom Wolfe entitled “The Artist the Art World Couldn’t See” about the sculptor Frederick Hart. Hart had a fatal handicap that cast him as a hopeless amateur in the art world — he could sculpt like a Renaissance Master. A masterpiece like Ex Nihilo, which had spiritual power and took 11 years of focused skill and inspiration, and would have won the respect of Michelangelo, couldn’t possibly be art.If Fredrick had created a sculpture that looked like a fifty-foot tall rusting coat hanger stuck in the ground, that would be art. But to commit the faux pas of using skill in connection with a work of art, and, God forbid, spiritual themes, meant that he didn’t show up as even the faintest blip on the art world radar. (In The Mission of Art, Alex quotes art historian Rosalind Krauss: “Now we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention ‘art’ and ‘spirit’ in the same sentence.”) The 2012 film, Cloud Atlas, is a masterpiece (see my review), but it was largely dismissed by critics, many of whom seemed to find its inclusion of spiritual themes to be unacceptable. For example, film critic John Serba wrote:

“Destiny, kismet, serendipity, karma — whatever you want to call it, ‘Cloud Atlas’ is full of it. And when I say ‘full of it,’ I mean ‘it’ to be New Age pseudo-spiritual baloney. ‘Everything is connected,’ the film’s tagline reads, and those who subscribe to that philosophy are more apt to be moved by its purported profundities.”

In other words, politically correct moviegoers, those sophisticated enough to realize that everything is disconnected and meaningless, can’t possibly support a film spreading outrageous spiritual propaganda like “everything is connected.”

No serious art critic would even review Hart’s spiritually themed masterpiece, Ex Nihilo. As Wolfe put it, “The one mention of any sort was an obiter dictum in The Post‘s Style (read: Women’s) section indicating that the west facade of the cathedral now had some new but earnestly traditional (read: old-fashioned) decoration.” If Hart’s use of skill and spiritual themes weren’t offensive enough, he added insult to injury by becoming America’s most popular sculptor.

Popularity with the general public is the ultimate disconfirmation of artistic value as far as the serious art world is concerned. According to Wolfe, “Art worldlings regarded popularity as skill’s live-in slut. Popularity meant shallowness. Rejection by the public meant depth. And truly hostile rejection very likely meant greatness. Richard Serra’s ‘Tilted Arc,’ a leaning wall of rusting steel smack in the middle of Federal Plaza in New York, was so loathed by the building’s employees that 1,300 of them, including many federal judges, signed a petition calling for its removal. They were angry and determined, and eventually the wall was removed. Serra thereby achieved an eminence of immaculate purity: his work involved absolutely no skill and was despised by everyone outside the art world who saw it. Today many art worldlings regard him as America’s greatest sculptor.”

Long before Ex Nihilo was dismissed by the art world, a Looney Tunes cartoon about a sculpture competition prophetically anticipated the undervaluing of Fredrick Hart. Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd enter a sculpture contest. Elmer obtains a huge slab of marble and sculpts a general sitting on a rearing horse. Just as he is finishing up, his chisel slips and one of the horse’s legs come off. He has less marble now, and uses the remainder to make a sculpture of a standing person. Elmer slips again when he is almost finished and has to discard that statue. Finally, he ends up with a sculpture of a mouse that he entitles The Mouse. As he is putting the finishing touches on The Mouse, Bugs Bunny casually enters his studio, picks up a jagged hunk of discarded marble, and asks Elmer Fudd if he can have it. Elmer distractedly assents. Bugs Bunny stands the rock up on a pedestal and entitles it Upwards Through Time and wins first place in the sculpture contest. My plot synopsis of the cartoon might be off by a detail or two, but you get the idea.

In another sphere of high culture, J.R.R. Tolkien and other writers of fantasy literature are similarly disdained by most literary critics for not realizing that a downbeat account of a series of failed relationships is the only subject sophisticated enough to be considered literature. Literary critics, like Harold Bloom, seemed to be in a hobbit-kicking competition. Edmund Wilson, who was once considered America’s preeminent man of letters, dismissed The Lord of the Rings as “juvenile trash.” There are some signs that attitudes are changing. Stephen King did get the National Book Award in 2003. However, the world of literary criticism still doesn’t seem to realize that fantasy is not a contemporary sub-genre, but the mainstream of literature, with classics like Beowulf and The Odyssey that were created millennia ago. It is in great works of fantasy literature that we often get glimpses of the hidden realms that Alex paints.

Instead of reducing fantasy literature into a subgenre, and calling downbeat books about failed relationships “literature,” I propose that only fantasy fiction should be called “literature” and the downbeat, failed relationship books be consigned to the following subgenre: “Nonvisionary/Personal-Neurotic.” Someone once said: “Don’t read a book unless it is like a ball of light glowing in your hands.” I’ve had that experience more often reading great fantasy novels than most “serious” literature and I was an English major with a couple of degrees and an English teacher for many years. I want all art that I encounter to be a ball of light in my hands, or even better, a ball of light I can step into. I propose that high art be defined as that which generates a ball of light in your hands, head or entire being, and all the rest should be consigned to subgenres with condescending names.

The 2006 film, Art School Confidential, is a wonderful spoof of what’s wrong with the art world. John Malkiovich plays a neurotic art teacher who only paints triangles and heaps scorn on any student naive enough to apply skill to their art projects.

So what is this “art world” that barely notices a visionary genius like Alex Grey? According to Wolfe,

“…the art world was strictly the New York art world, and it was scarcely a world, if world was meant to connote a great many people. In the one sociological study of the subject, ‘The Painted Word,’ the author estimated that the entire art ‘world’ consisted of some 3,000 curators, dealers, collectors, scholars, critics and artists in New York.”

On the morning I started writing this, the same morning that Caleb told me that he saw ghosty things other people didn’t see, there was another stunning synchronicity. While making breakfast, I put on the next Charlie Rose interview that happened to be waiting in my DVR queue. I knew I was going to be watching Charlie Rose, but I had no idea what guests were on. Up next turned out to be an interview with Arne Glimcher, a true princeling amongst art worldlings, the owner of five art galleries, including New York’s influential Pace Gallery. Arne had just written a book about the minimalist artist, Agnes Martin. One minute and five seconds into the interview, Arne laments the ignorance of people (what wretched idiots we are!) who think art has anything to do with skill. Glimcher:

“I think people don’t understand really that art is something in the mind not in the hand. So many people have enormous skill, can make beautiful portraits, can render what they see, so few people can interpret reality.”

Glimcher seems to have done a statistical analysis by proclamation and claims that people with “enormous skill” are a dime a dozen and much more common than his elite class of reality interpreters. First of all, Arne, all art, good or dreadful, abstract or representational, interprets reality. Second, where are all these “so many” folks with enormous skill who are apparently too numerous to be worthy of consideration? I don’t have any statistics either, but last time I checked, I noticed a lot more people doing sloppy, conceptual art projects than people who merely had “enormous skill.”

Oh, but how silly of me, I forgot that art worldlings are here to interpret reality for the rest of us, and to represent reality accurately on canvas or in public statements would be a descent into tasteless, hoi-polloi mediocrity. Perhaps the world of high art and the Tea Party are destined to be allies, since both feel empowered to interpret reality in anyway that feels convenient and both heap scorn on those who seek to represent things accurately.

Glimcher’s nonsensical assertion that only the elite of artists “interpret reality” tells us that the art world is rife with pseudo-intellectualism. Highfalutin sounding statements filled with jargon that don’t even begin to make sense are passed off as if incomprehensibility were a sign of high intellect. The pseudo-intellectualism of art wordlings is the perfect bait to phonies seeking culture as status symbol. Privately such status-seekers think that someone making incomprehensible statements must be smarter than they are, and that their best chance of appearing cultured is to meekly defer to the judgment of art worldlings.

And Mr. Glimcher is full of judgments he expects us to defer to. In this one fourteen minute interview he is going to give us several more fascinating glimches into what constitutes high art. In the second minute of the interview, Glimcher provides a list of elite artists who don’t touch their own artwork, but hire other people to do it or create it digitally. “And you are saying what about those people?” asks Charlie Rose. “I’m saying that they are some of the best examples of art being a product of the mind, rather than the hand.” Apparently this is Glimcher’s most central discrimination: art of the hand vs. art of the mind. Notice that this is a nonsensical distinction. Opposable thumbs have been redefined as a counter-evolutionary development.

Perhaps if he had watched Charlie Rose’s brain series, he might have learned this interesting finding from neuroscience: Hands are often controlled by minds. Using your hand does not make you mindless, and if you instead use these unfortunate appendages only to touch a computer mouse or to pick up a phone and call other people to tell them how to do the messy, physical part of your art work, that does not make you more imbued with mind. It does not make you more of a “reality interpreter” than anyone else. It does, however, make it 72% more likely that you are pretentious asshole. Artists who are handicapped by having hands under intelligent, skillful control are still able to make art imbued by mind. The only thing I get from Glimcher’s favorite distinction is a snotty, upper class disdain for manual labor. Like a CEO, you become a member of the art elite by being as removed as possible from physical participation with the finished product.

Glimcher further clarifies his disdainfulness for the physical by condescending to recognize architecture as an art (barely), but a handicapped art that could never rise to the level of, for example, one of Agnes Martin’s smears on graph paper.

“Architects can, you know, make great works of ar—”

Glimcher breaks off mid-syllable, preventing himself from accidentally crediting architects as being capable of great art. He corrects the slip and continues:

“Great works of architecture. I think, for the most part, architects are utilitarian artists.”

Glimcher disdainfully over-enunciates “utilitarian” in a way that indicates that it is a synonym for “mentally retarded.” He continues: “It is not, it’s great, it is not the same level, for me, as painting and sculpture where they are non-utilitarian. They are something that just extends the perception of the mind.” (Of course, a utilitarian object like a computer could never extend the perception of the mind. Only things hanging in the Pace Gallery could possibly do that.)

Rose ignores this dismissal of architecture as one of the janitorial arts, and tries to steer the interview back to something that Glimcher does know about: “Tell me who Agnes Martin was.” Glimcher:

“Many people call Martin the beginning of minimalism. She’s the end of abstract expressionism. Because there is brushwork, there is a sensitive application by hand. Minimalism sought to get rid of all possible human marks on a canvas.”

Glimcher over enunciates “human marks” to indicate that it is a synonym for dog shit. Martin sweeps away these unsanitary human marks,

“And she eliminates everything from the picture. There is at first no color, no composition. She begins making paintings that are grids that look like graph paper with pencil on canvass…she said to me that she wanted to make a painting that no one else would recognize as a painting. And you know, they responded.”

Glimcher smiles to indicate that Martin had received the ultimate recognition of creating art that no one recognized as art.

This statement generated a flashback to something my dad, Nathan Zap, warned me about in the Museum of Modern Art when I was about twelve years old. My dad was an expressionist/ surrealist painter (see Nocturnal Visions — The Paintings of Nathan Zap) and I grew up going to New York art museums on at least a monthly basis. The first pictures of my parents dating in the late 1940s were taken in the Museum of Modern Art sculpture gardens.

Even as a small child, it was obvious to me that some modern art was visionary, and some of it was a hoax. (An art hoax that costs $50,000 or more is called a “Glimcher”) When I was twelve, we walked past an absurdly minimalist painting, and I ventured the opinion that it wasn’t even art. My dad rebuked me sharply,

“Never, ever say something’s not art, and never, ever act outraged by art no matter how bad it is. There is always some chance that the artist is present and you’ll be giving them exactly what they want. They live for the hope that their art will outrage someone, or that someone will say it is not art. Just walk by it looking bored.”

He was exactly right, of course, and his advice has always stayed with me. There is a great shortage in the art world of people who will act outraged at unskillful art. Such art has been a banal and predictable stereotype for many decades. These are objects of boredom, not outrage. This type of artist is reduced to begging for outrage and disapproval, like Marilyn Manson in the classic Onion article: Marilyn Manson Now Going Door-to-Door Trying to Shock People.

The interview continues, and we finally see some of Martin’s work, beginning with a painting that looks like a sun-faded Rothko. Glimcher narrates: “This is the beginning of Martin’s mature work…it’s not mature yet, but she’s beginning to limit the amount of content in the painting.” This is another fascinating glimche into the nature of high art. An artist is mature to the extent that they have reduced or eliminated content from their art. An artist like Alex Grey, whose paintings are filled with mesmerizing content, is, therefore, an immature artist. That Alex’s art is recognizable as art due to his naive inclusion of content shows just how lowbrow it is. That his content is realized by the skillful use of hands lowers it even further.

Glimcher is not alone in his contempt for art that has content or that is recognizable as art. Sophisticated art must be nihilistic and expressive of nothing except contempt for the public. In The Mission of Art, Alex quotes the contemporary German painter Georg Baselitz as an example of this sort of trendy and contemptuous nihilism:

The artist is not responsible to anyone. His social role is asocial; his only responsibility consists in an attitude to the work he does. There is no communication with any public whatsover. The artist can ask no question, and he makes no statement; he offers no information, and his work cannot be used.

Next on the screen we see a painting entitled Pilgrimage, which looks like an unskillfully rendered portrait of a piece of corrugated, brown cardboard. Commenting on the blurry cardboard, Glimcher gives us another glimche into high-art perception:

“This is a really great, great painting…the way you have to look at these paintings is by erasing any kind of prejudice about what you think you’re seeing and look at the painting and it becomes a mantra.”

In other words, to see high art like this, you have to stop believing your lying eyes, check your mind at the door, and instead repeat the mantras of art worldlings like Glimcher while opening your check book. It’s an amazing glimche into the doublethink/doubletalk of an art worldling. Most of the content of Glimcher’s interview has been a recital of his prejudices against architecture, or any form of art that has been touched by human hands or that has utility or content. What we think of art is prejudice, what Glimcher thinks of it is revealed truth. To know art we must become empty vessels so that art worldlings like Arne Glimcher can fill us up with their contentless notions.

Next we are shown a painting entitled Trumpet that looks like someone has smeared charcoal on a blank accountant’s ledger. Off camera you can hear Charlie Rose shuffling papers impatiently, and you can sense his hangdog expression drooping by several degrees, until you can almost see a clock melting over his face, which is lying deflated on his oak table, a PBS transposition of the The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali. The fourteen minute and twenty second interview has become like watching pencil shadings drying on graph paper, and I can feel the embarrassment of my new LED monitor as it reluctantly surrenders its pixels to render up these colorless, contentless images. Next we are shown Homage to Light, which consists of a black trapezoid on a smeary background. Glimcher describes this masterpiece,

“You have this fantastic wash background…this rectangular shape is an echo of works from the Fifties…I see it as a kind of infinite void, infinite background, void of a background, with this concrete shape floating on it. I think these are open to incredible interpretation.”

Indeed. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to erase my prejudices enough. The trapezoid was still a trapezoid, even though Glimcher referred to it as a rectangle (in fairness, they are both quadrilaterals). To paraphrase Louis Armstrong, “If you have to ask what a rectangle is, you’ll never know.” I guess I’m still stuck in a trapezoidal box when it comes to recognizing the value of unskillful, contentless art. The interview ends with a perfect logical tautology. Charlie Rose quotes an assertion Glimcher made in their previous interview: “The Western narrative is over.” A Westerner asserts a narrative that the Western narrative is over. Arne has forced me to see ants scurrying around the Möbius strip of his thinking. Now that’s art of the mind.

Exposing “Casual Sex” as an Oxymoronic Delusion and Other Third Rails

Copulating

The sophisticated person is supposed to have thoroughly demystified sex into a series of hydraulic transactions that high art should view cynically, emphasizing the lurid and grotesque aspects.

Alex, in paintings like Kissing, Copulating, Embracing, and Tantra, violates this taboo by revealing the as above, so below interconnection of sexuality and spirituality. Promiscuity, the current patriarchal norm, is often just as toxic as the old patriarchal norm of harsh taboos. (see my essay: Born under a Blood Red Moon — Metamorphosis of the Feminine in the Dreams of Young Women) Contemporary promiscuity and harsh taboos are opposite sides of the same patriarchal and unerotic coin. (Eros is defined in many different ways in psychology, philosophy and popular culture. Here it is used to refer to the capacity for oceanic merger with other beings.)

What are sometimes called erotic images are often depictions of unerotic sex on the level of the genitalia. Alex’s erotic images transcend both sides of the patriarchal view of sex. In a way, his images are more explicit than pornography, which exposes the topography of naked bodies. Alex’s images make the skin transparent so we see the internal organs. At the same time he reveals the interpenetration and merger of bioenergetic and spiritual energy fields. Professor Emeritus of Physiological Science at UCLA, Valerie V. Hunt, has done experiments that demonstrate that in many cases strangers sitting near each other (in laboratory conditions where they can’t hear, see, or smell if another person is nearby) will have potent effects on each other’s bioenergetic fields, which will tend to become mutually entrained.

Imagine how much greater these effects are if, instead of proximal strangers that can’t be detected by ordinary senses, we have two people having sex. This is why there can be no such thing as “casual sex.” Sex is not casual on the microbiological plane — it can begin a new life and it can sometimes end a life through STDs like AIDS. As below, so above. It is also not casual on the bioenergetic and spiritual energetic planes. Many of the people who admire Alex’s artwork (Burning Man folk, etc.) don’t seem to get this aspect of what it reveals, and are still naively promiscuous, or even fall for the pre/trans fallacy and believe that sexual antics are daring, avant-garde and transcendent of the conventional. (see Incendiary Person in the Desert Carnival Realm for a critique of Burning Man eros) If you’ve looked at Alex’s paintings and you still believe in “casual sex,” you have not really seen them.

Growing up in New York City and taking the subway on a daily basis I was always fascinated by the forbidden third rail, crackling with 625 volts of lethal electricity. It was both dangerous and fascinating, and a powerful taboo forbade ever going near it. But there was always, and is still, some counterphobic desire to draw near to it, to see what it would be like close up. I feel my hand wanting to reach for it. I, I can’t stop myself, I am going to touch it right now: ABORTION.

Alex’s artwork has profound implications concerning abortion. Many people who look at it don’t see this, just as they don’t see its implications for casual sex. Alex’s painting Pregnancy and his series of paintings in Transfigurations that begin with Attraction, and continue through Penetration, Fertilization, and Buddha Zygote, illustrate phases in the development of embryo and fetus with medical illustrator exactitude.

They also address an issue that many would prefer to skirt around: When is a soul associated with a developing human body? In Alex’s paintings, the answer seems to be conception. Alex paints soul mandalas even at the moment just before conception. He is illustrating a Buddhist teaching that souls choose to enter the organic world at the moment of conception.

Valerie Hunt, on the other hand, based not on science but on what she claims is a near consensus of intuitives, says that it is after the first trimester. Perhaps there is a necessary degree of tissue complexity, and especially neural complexity, before a body can house a psyche. Here’s my position on the subject: I don’t know. What I do know is that this is the essential question that needs to be addressed before I can know what to think of abortion. Abortion is not merely a political third rail; it is also an ontological third rail. How and when do psyche and physiology associate and how and when do they disassociate? (see: The Glorified Body—Metamorphosis of the Body and the Crisis Phase of Human Evolution). I don’t know if the association in Alex’s paintings is correct, but his images are powerful reminders to me that I don’t know, and that this crucial, unanswered question crackles with dangerous electricity.

Alex responds to the Invisible Giant section

I’m just now re-reading and even though it speaks to your theme of my invisibility in the artworld, there were a few other times the Times covered my work:

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/01/03/garden/at-home-with-alex-and-allyson-grey-tuition-and-other-head-trips.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/04/arts/art-in-review-alex-grey.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/23/nyregion/thecity/23lsd.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/20/arts/design/20sacr.html

[The article I excerpted as evidence of condescension — JZ]

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/08/arts/design/08tomaselli.html?_r=0

[A Times review of a showing of Fred Tomaselli which makes reference to Alex — JZ]

Alex adds:

In a Ken Johnson review of well respected ARTworld star, Fred Tomaselli:

“Unlike the psychedelic painter Alex Grey, whose art conveys a true believer’s faith in the reality of an ultimately beneficent divinity accessible by means of “entheogens” — drugs that activate inner gods — and practices like meditation and chanting, Mr. Tomaselli teeters on the agnostic line between belief and skepticism.” –Ken Johnson

Here’s Fred Tomaselli’s endorsement:

“There was a time when expeditions into the unknown were always accompanied by an artist to depict the newly discovered landscapes. Alex Grey is one of those kinds of artist, but in his case he explores our parallel realities and brings them back alive. He is the Albert Bierstadt of inner space.”?? –Fred Tomaselli, artist

Perhaps you could just say my work is lost in the convolutions of the artworld. I have been in museum shows over the years, New Museum of NYC, Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, etc. more than most “visionary artists” so in some ways I’ve been fortunate.

This is part 1 of a multi-part overview. Find Part 2 here.

Alex’s three Monograph books are: Sacred Mirrors, Transfigurations and Net

of Being. Click on this link: CoSM Store to buy these directly from Alex.